Truly this is Golden’s touch, to give us the moment tinged with feeling…[by] putting his own enthusiasm on paper with sensitivity and style.

Tall, gregarious, affable and easygoing, Francis Golden is a whirlwind of abundant energy.

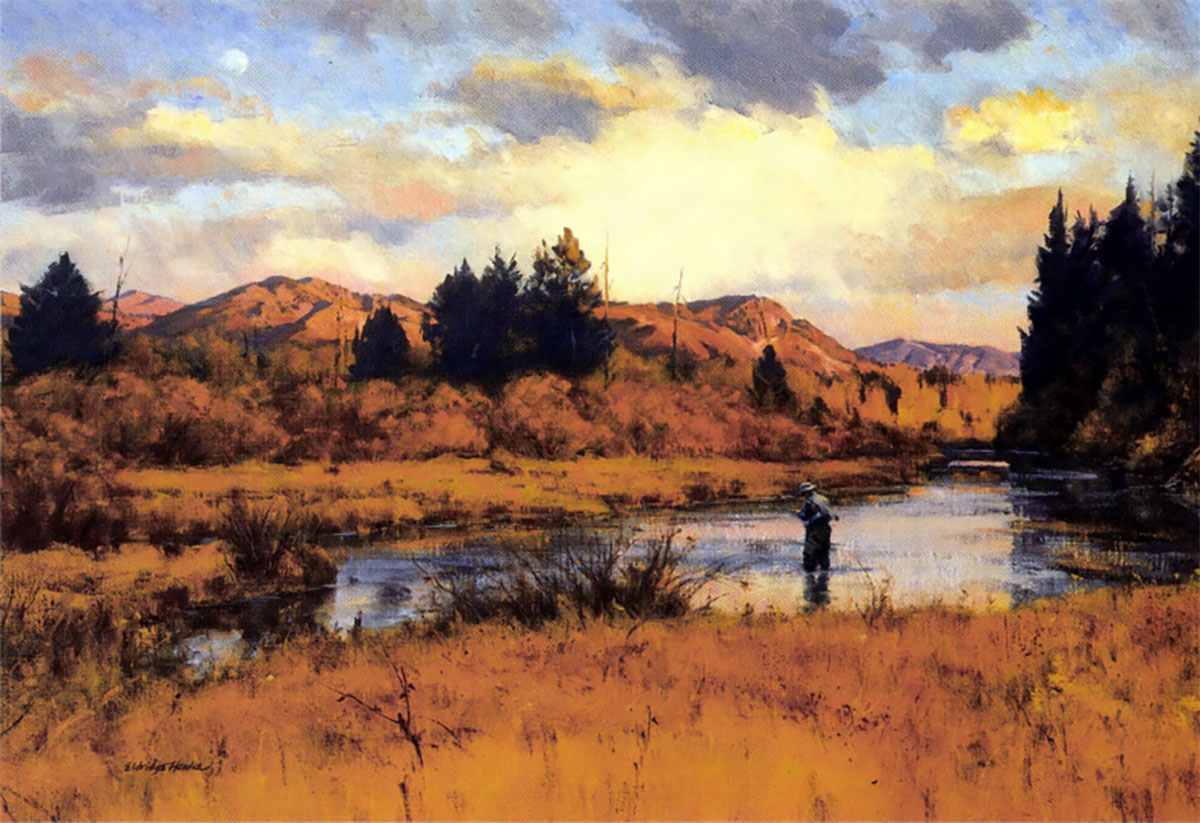

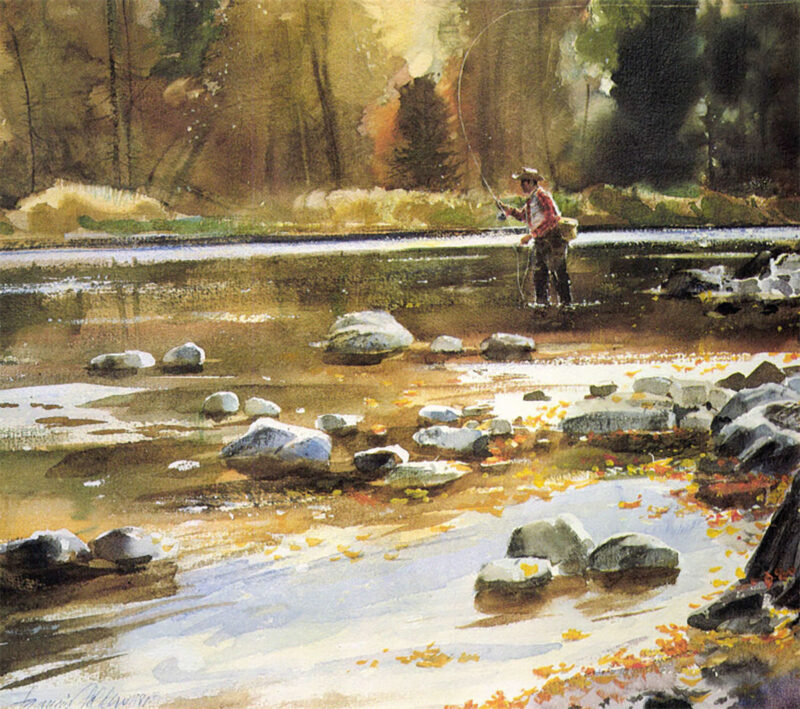

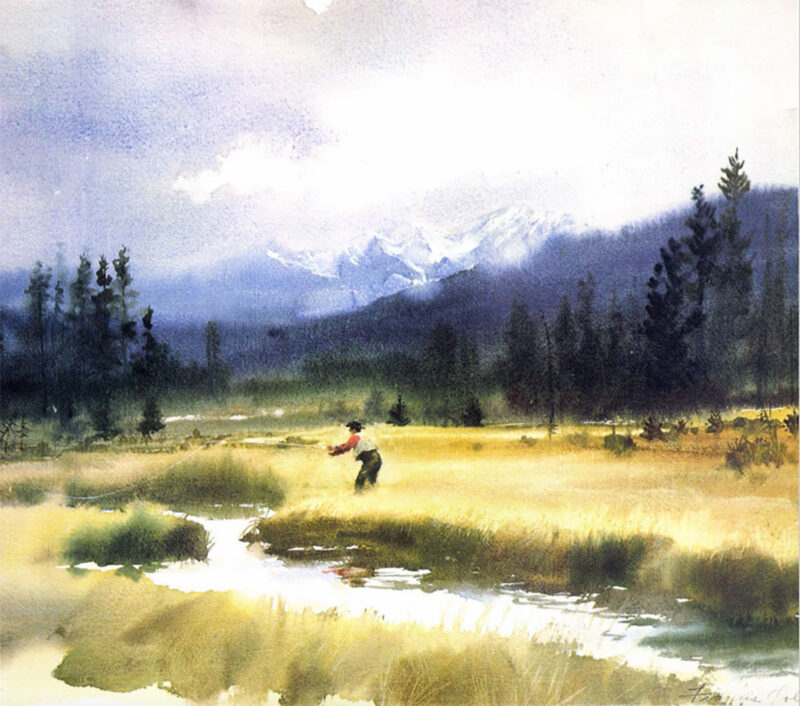

I am not a fly fisherman, but the experience of standing in a rushing stream casting to trout lurking in deep pools is something I find easy to imagine, especially when I look at a watercolor by Francis Golden. Golden is a fly fisherman, and his scenes of this most mesmerizing sport weave an enchantment akin to that of Norman Maclean’s haunting story, A River Runs Through It:

“On the Big Blackfoot River above the mouth of Belmont Creek the banks are fringed by large ponderosa pines. In the slanting sun of late afternoon, the shadows of great branches reached from across the river, and the trees took the river in their arms. The shadows continued up the bank, until they included us.

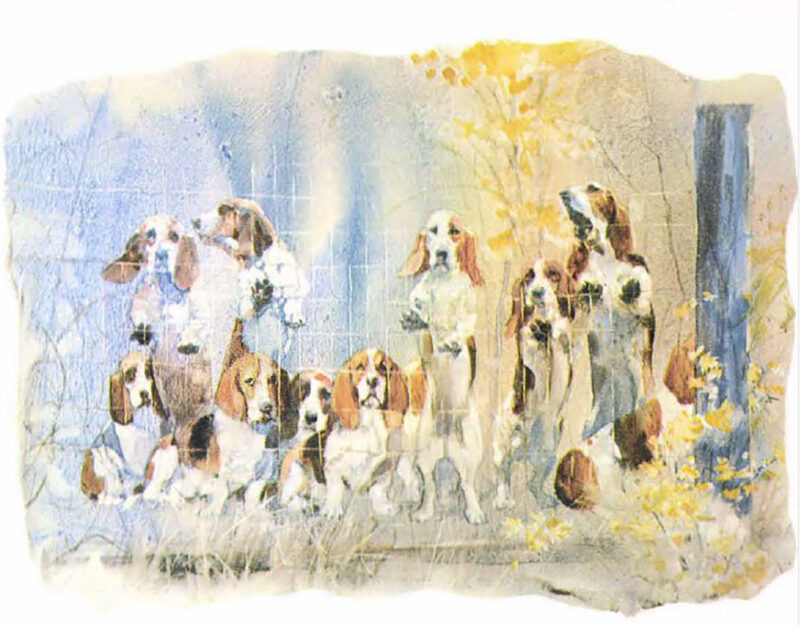

Golden is a versatile painter and a skilled outdoorsman. Basset hounds in Dutchess County was one of the many illustrations commissioned by Sports illustrated over a 20 year period.

“I often do not start fishing until the cool of the evening. Then in the Arctic half-light of the canyon, all existence fades to a being with my soul and memories and the sounds of the Big Blackfoot River and a four-count rhythm and the hope that a fish will rise.”

What Maclean does with words, Golden does with a brush. He readily admits that fly fishing is his favorite pastime, but when asked to elaborate, he becomes shy, perhaps protecting this private pleasure from the intrusion of outsiders. He says simply, “I just love it.” Instead of words, Golden uses watercolor to express his feelings about fishing. When you look at his paintings, there is an overpowering reverence for nature. Like the centuries-old Chinese landscapes on silk, Golden’s scenery is the dominant element, his figures small, a significant imbalance important in oriental philosophy indicating man’s acquiescence to the dominion of natural forces.

This scene of trout fishing in Maine typifies the Golden touch and his ability to capture a moment tinged with feeling.

Best of all, like Maclean’s creeping shadows, Golden’s paintings include us. In the filtered sunlight he deftly recreates, we can feel the coolness of the shade, bask in the serenity of the place and even hear the running of the river. This is Golden’s magic.

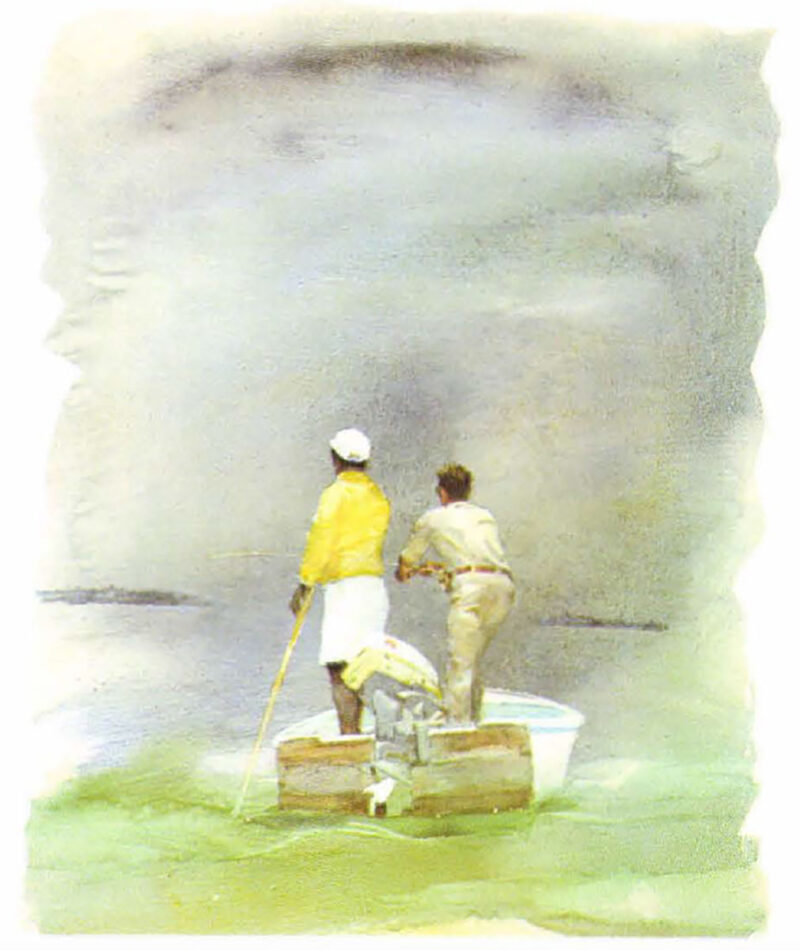

Bonefishing the Florida Flats, originally in Sports Afield, shows the confidence and skill with which Golden executes a watercolor.

It is hard to imagine this tall, gregarious man standing quietly at his easel, totally absorbed in the solitary task of painting. Affable and easygoing, he is a whirlwind of abundant energy. Whether he is singing tenor in the local barbershop quartet, digging a new flower bed in the garden, piloting his Crestliner into Long Island Sound after bluefish, or baking his famous apple pie, Francis Golden embraces everything with an infectious enthusiasm.

Yet he makes his living standing quietly, for long hours, at his drawing board. Perhaps it is the intense concentration required for the unforgiving medium of watercolor that seeks diversion in all his other activities, or perhaps it is Golden’s overflowing energy that attracted him to watercolor in the first place. One of its great assets is that it lends itself to the spontaneous expression of the artist. As Golden himself puts it, “I like to work fast and loose. With watercolor, each painting is like a happening. I have an image in mind when I start, but I’m never quite sure how it’s going to tum out. That’s part of the excitement of painting in watercolor. ”

I visited Frank Golden one sunny afternoon at his home in Weston, Connecticut. His studio is a room in the back of the house, overlooking the garden and woods beyond, tranquil and conducive to concentration. Sliding glass doors admit northeastern light, important to an artist for its true rendering of colors. His easel was hidden from view by the surf-fishing rods propped against it, and one corner of the studio was stacked with fly rods in cases. A few guns adorned one wall. Golden has not hunted in years, and recently, after a neighbor was robbed, he sold most of his 200-gun collection. He now keeps only his father’s shotgun, his first Winchester. 22 and a few air rifles. In the middle of the studio stand stacks of paintings, framed and unframed, some waiting to be shipped off to dealers, others returned to him after being printed by the magazines that commissioned them.

I visited Frank Golden one sunny afternoon at his home in Weston, Connecticut. His studio is a room in the back of the house, overlooking the garden and woods beyond, tranquil and conducive to concentration. Sliding glass doors admit northeastern light, important to an artist for its true rendering of colors. His easel was hidden from view by the surf-fishing rods propped against it, and one corner of the studio was stacked with fly rods in cases. A few guns adorned one wall. Golden has not hunted in years, and recently, after a neighbor was robbed, he sold most of his 200-gun collection. He now keeps only his father’s shotgun, his first Winchester. 22 and a few air rifles. In the middle of the studio stand stacks of paintings, framed and unframed, some waiting to be shipped off to dealers, others returned to him after being printed by the magazines that commissioned them.

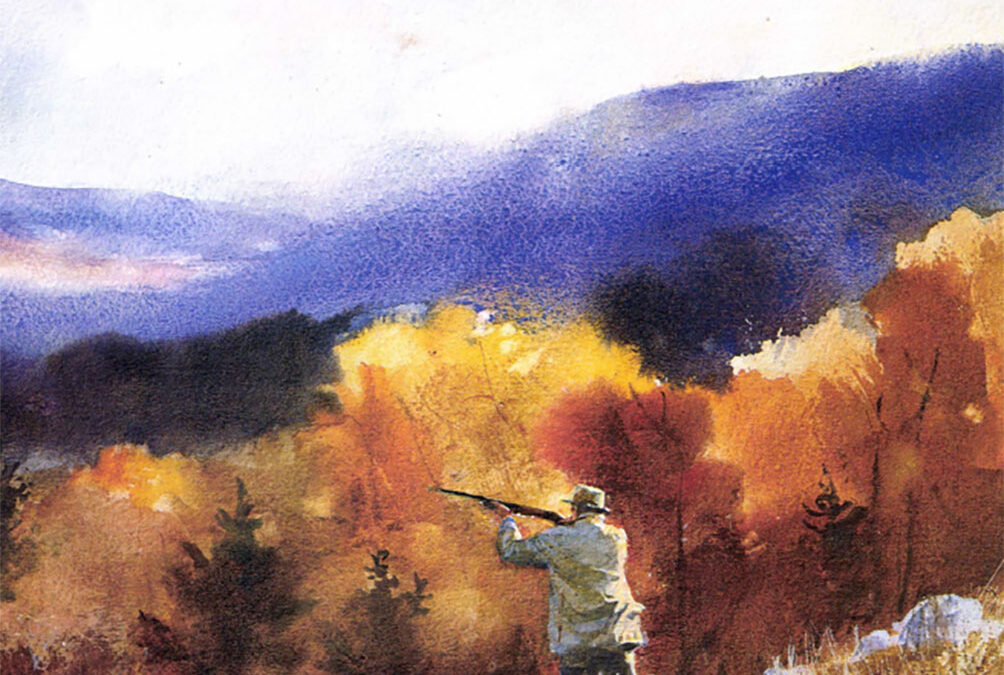

Golden likes to work fast and loose with watercolor as in this scene depicting duck hunting along the Mississippi delta. He feels each painting is a “happening” and is never sure how it will turn out.

Golden is best known for his sporting scenes which have appeared in the pages of Sports Illustrated, Sports Afield, Gray’s Sporting Journal and Audulxm. His career as an artist began as a boy fascinated with paint and color. Born in 1916, in Adams, Massachusetts, Golden did not have ready access to art classes or proper materials. Most of the time, he used Benjamin Moore paint and brushes from the hardware store. When his mind was made up to pursue his artistic inclinations, he traveled east to study at the Boston Museum School of Fine Arts. He was all set to establish himself in Chicago as a commercial artist when a friend persuaded him to come to New York and work on murals and backgrounds at the 1939 World’s Fair. By the time the fair work was completed, Golden had decided to pursue his ambitions in New York.

In 1940, he was hired as a free-lance artist by J. C. Penney to create signs and posters for their stores, on a $22 per week retainer. During World War II, the draft was thinning Penney’s art staff, and Golden (rheumatic fever as a child had left him with a heart murmer) found his services much in demand. His retainer was increased to $500 a month, a good salary for a free-lance artist in those years.

Trumpter Swans in Winnepeg is one

of the few paintings Golden has done in acrylic.

Collier’s was the first magazine to commission his work. That was in 1946. Within two years, Golden was employed full-time doing magazine illustrations. His greatest opportunity came in 1961, when Sports Illustrated revamped its look under a new editor in an effort to turn a profit. It was decided that a more exciting look would broaden the magazine’s appeal, attract a younger readership and increase circulation. Richard Gangel was hired as art director to create the new look, and along with action photography and lots of color, Gangel also wanted artwork with a dynamic approach. Having worked with Golden in the past, and knowing him as a versatile painter as well as a skilled outdoorsman, he sent him off on his first assignment to illustrate hunting of upland birds.

Gangel considerers Golden’s style to be “traditional in the Winslow Homer school,” but quickly adds that Homer is “very contemporary because of his unmistakable vitality.” This so-called traditional style made Golden an ideal choice for illustrating experience-oriented stories for Sports Illustrated. As Gangel put it, the reader “needs to understand what is going on. Golden is very much a visual storyteller.”

Over the next 20 years, Golden was a regular contributor to the magazine, and built a following of readers who looked forward to each piece. He honed their golf swings with Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, took them fishing for roosterfish in the Gulf of California with Jon Tarantino, and showed them the secrets of Johnny Unit as’ forward passes.

Over the next 20 years, Golden was a regular contributor to the magazine, and built a following of readers who looked forward to each piece. He honed their golf swings with Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, took them fishing for roosterfish in the Gulf of California with Jon Tarantino, and showed them the secrets of Johnny Unit as’ forward passes.

After all those years of meeting deadlines, Golden is happy too slow down a little and do more of what he loves — easel painting. But this is not as simple as it sounds. Golden has encountered problems in trying to produce larger scaled works for his galleries. As he explains, “A loose style holds together better in a small size and doesn’t translate well to something bigger. I find I have to put in more detail to hold the overall picture together, and that takes more time. I can’t work as fast as I used to.”

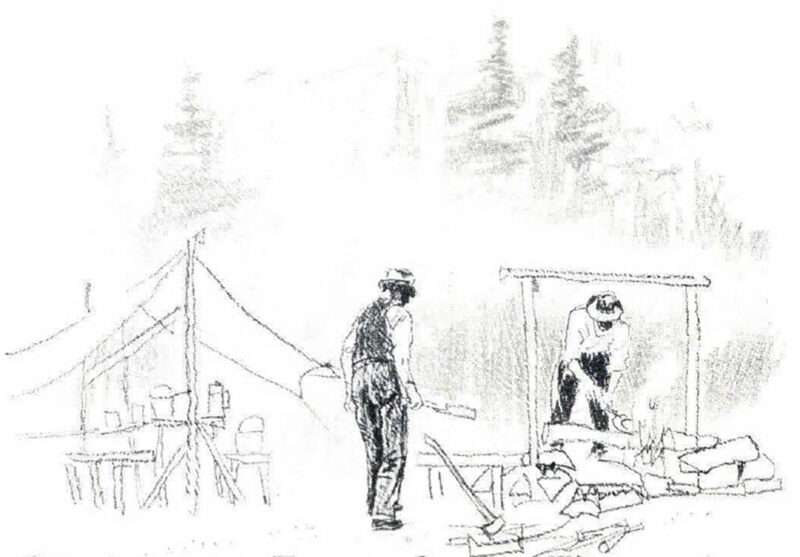

Golden’s scenery is usually the dominant element in a watercolor. Goose hunting at the Tabusintac Camps in New Brunswick typify how he likes to keep his figures small.

An artist painting in oils can scrape out or paint over his mistakes without marring the finished product. But in transparent watercolor, once the paper absorbs the pigment and dries (which it does in about 20 minutes), the color can only be taken out by scratching. It takes confidence and skill as a draftsman to paint in this medium.

Theodore Wolff, art critic for the Christian Science Monitor, compares watercolor to walking a tightrope, with no margin for error. “Watercolor demands total honesty and a thorough mastery of its craft. We know immediately upon seeing one whether or not it ‘works,’ just as we know without question whether or not an acrobat makes it safely across a tightrope.”

Golden agrees. “If I blow it, I just have to take another piece of paper and start over.” His watercolors, however, show no sign of intimidation. His brushwork is energetic, and most of his paintings look as if they were rapidly executed. In reality, some may take days.

Wolff, in his defense of watercolor, states that “many of those who paint in watercolors claim they are the ‘poor relations’ of the art world. Their complaints, unfortunately, are quite legitimate. The world at large does take watercolor less seriously than oils. The problem, I suspect, lies in the informality of the medium. It’s too sketchy and light spirited. “As we sipped tea in the shade on the patio outside his studio, Golden talked about this second-class status. Because oils were the medium for the Old Masters, the art world seems to feel it is the only one that counts. Golden resents the high prices that oils and acrylics can command, whereas he has to settle for $1,800 to $2,000 for one of his originals.

Wolff, in his defense of watercolor, states that “many of those who paint in watercolors claim they are the ‘poor relations’ of the art world. Their complaints, unfortunately, are quite legitimate. The world at large does take watercolor less seriously than oils. The problem, I suspect, lies in the informality of the medium. It’s too sketchy and light spirited. “As we sipped tea in the shade on the patio outside his studio, Golden talked about this second-class status. Because oils were the medium for the Old Masters, the art world seems to feel it is the only one that counts. Golden resents the high prices that oils and acrylics can command, whereas he has to settle for $1,800 to $2,000 for one of his originals.

Gallery sales of some types of his watercolor paintings have not been a rip-roaring success, and Golden is somewhat disappointed. Fred King, owner of Sportsman’s Edge and King Galleries, feels that “fishing scenes just don’t sell. Fishermen don’t spend on art the way hunters do.” Byron Webster, of Wild Wings, also handles Golden’s work, and agrees that the hunting scenes outsell the fishing. Wild Wings sells a lot of the original illustrations that were done for Sports Illustrated, and to Webster this is not a deterrent. “People are surprised when they walk into the gallery and see his work on the walls because they recognize him, but didn’t realize they could buy his originals.”

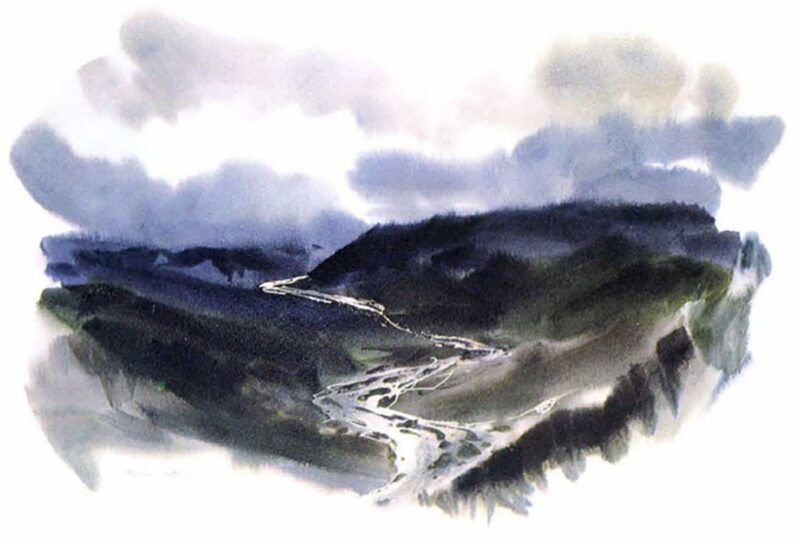

This scene of an Alaskan river exemplifies Golden’s loose style.

So far, Golden has only reproduced three works, a salmon fishing print for the Atlantic Salmon Association in Montreal, a trout fishing print for Sportsman’s Edge and a family of Canada geese for Wild Wings. Although Golden doubts whether these prints have been a success, his dealer, Byron Webster, disagrees. The goose was printed in an edition of 850 in 1981, at $65 each and some are still available. Webster claims “it is a warm piece, with blues, yellows and greens, that appeals to the ladies — easy for a woman to decorate a room around.” Sporting art has a predominantly male following, and yet the non-sporting scenes seem to reach a wider audience, even interior decorators.

Golden has a storehouse of memories, as well as many black-and-white photographs he has taken over the years for his own reference. “Black-and-white is better for me,” he explains, “because I don’t want to be influenced by the colors of Kodachrome. My own memory for color is better, and besides, color is part of the joy of painting.”

Golden is best known for the illustrations he does for sporting magazines. This illustration of a stream in Idaho was the lead for an article entitled Lonely Places which appeared in Sports Afield.

Les Line, editor of Audulxm, uses Golden’s watercolors in a magazine generally known for its photography. As he puts it, Golden’s paintings “offer a truly refreshing reflection of nature and the out-of-doors, a reflection more honest to what our eyes actually see than the finely detailed paintings to which we have become accustomed in recent years.”

Truly this is Golden’s touch, to give us the moment tinged with feeling, perhaps evoking memories of past experiences the onlooker can share, or simply putting his own enthusiasm on paper with sensitivity and style.

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world.

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world.

Sieve paints in a contemporary style, with a keen eye for detail and a masterful understanding of animal behavior and anatomy that can only be learned through a lifetime of experience in the field. Meticulously realistic and beautifully composed, his paintings follow the artistic tradition shaped by wildlife legends Les Kouba and Bob Kuhn and continued by distinguished contemporaries such as Gary Moss, Robert Bateman and more. Buy Now