The novelist John Gardner posited that there are really only two stories: A man goes on a journey, or a stranger comes to town. With all due respect to Gardner’s memory, however, I’d like to add a third: The telephone rings, and you answer it.

The caller identified himself as Myron something-or-other, said that he’d seen a Field & Stream article I’d written on fall fishing in Wisconsin’s Door Peninsula (where I lived at the time), and added that a certain Lake Michigan charter captain, someone I knew slightly, had suggested I might be persuaded to show him a few spots.

“So you’re looking for a fishing guide,” I asked.

“That’s it, basically. I have a couple of friends with me who just flew in from Idaho. They own a fly-fishing lodge where I go every summer, and I thought it’d be fun to have them out here. I’ve heard that the fall fishing for trout and salmon can be spectacular. You do fly-fish, don’t you?”

“Uh, yeah, but I’m kind of busy and I’m not really a fishing guide….” Already, I could sense disaster. The semi crossing the center line. The iceberg looming up out of the fog.

The problem wouldn’t be showing them fish; that’d be easy. I could take them to any of the Door’s rockbound harbors or Lake Michigan tributaries and do that, including 25-pound chinooks, browns of a size that were guaranteed to blow their minds, maybe even the odd fall-run steelhead. Putting them in a place where they might catch one of these fish on a fly, however—especially given how little I knew about the finer points of fly-fishing at the time—was, as they say, a whole other ball game.

There were other complications as well, such as the fact that the best chances for a hook-up were at first light, and that these chances dwindled rapidly after sunrise. On the other hand, if the Idaho guys were such big experts, maybe I could just sort of point them in the right direction, stand back, and let them take it from there.

“I’d make it worth your while,” said Myron, “and it’d only be for the morning.” He came across as such a sincere, sweet-natured person that the reluctance I felt at setting myself up for a potential epic fail (read: making a complete fool of myself) was finally shouldered aside by the desire not to disappoint him.

“Wonderful!” he said. “We’ll look forward to seeing you in the morning, then. Why don’t you come by the boat about 7:30.”

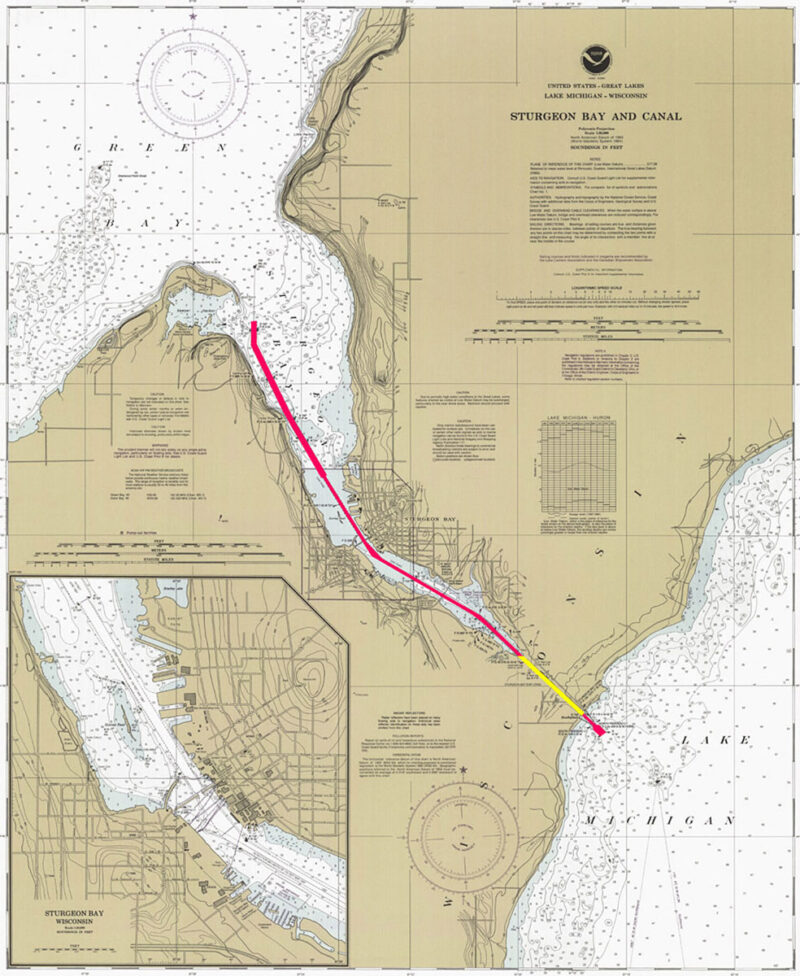

Sturgeon Bay and Canal

“The boat?”

“Oh, sorry, I forgot to mention that we’re staying aboard my boat—the Alianora. She’s docked at the Palmer Johnson yard in Sturgeon Bay. You can’t miss her; she’s a 72-foot wooden ketch. She needs some minor repairs and Palmer Johnson is the only yard I trust to do the work. We sailed her up from Chicago; I have a home there, but I spend most of my time at my place in the British Virgin Islands, the Bitter End Yacht Club.”

When I’ve told this story to friends who are in the sailing/cruising loop, this is where their jaws drop, their eyes grow wide and they say, “Wait—the owner of the Bitter End Yacht Club was in Sturgeon Bay having his 72-foot wooden ketch worked on at Palmer Johnson, and you took him fishing?”

“Yep.”

“And none of this struck you as unusual?”

“Not at the time….”

This is also where, looking back with the benefit of 30-plus years of hindsight, I realize how abysmally ignorant I was—and feel a hot prickle of shame at ever having been that person.

Bitter End Yacht Club, British Virgin Islands’ “end of the line.”

I showed up the following morning at the Palmer Johnson yard—my one and only visit to what was long regarded as one of the finest boatyards in the world. (The name lives on, but these days it’s attached to an address in Monaco. Seriously.) The Alianora, all varnished wood and polished brass and bristling spars, was an impressively handsome vessel, while Myron was exactly as I imagined him: an avuncular older gentleman, slender and white-haired, who seemed perpetually bemused. His friends from Idaho, John and Randy, were lean, tanned, typically Western-looking guys, and not a hell of a lot older than I was.

“Myron tells me you own a fly-fishing lodge,” I said, by way of breaking the ice. “Does it have a name?”

The two exchanged a quick glance. Then John, who did virtually all the talking, gave me a thin, forced smile and said, “It’s really kind of a private club. You have to know somebody.”

In retrospect this was bullshit—they didn’t want to open the door even a crack to the possibility that I might play the “writer card” and try to dun them for a freebie—but I was so naïve in those days that instead of being offended I just accepted it at face value and moved on.

“Well, before we do anything, we need to get everybody legal,” I said. “You can buy your licenses and stamps at Mac’s Sport Shop, right across the bridge. Just follow me; I’m driving the blue Chevy Luv.”

“We’re in the Suburban,” Myron said, pointing toward a shiny silver behemoth glinting in the morning sun. If theirs was the Mother Ship, mine—with its frisky aluminum-block four-banger and cab that seated two uncomfortably—was the dinghy.

We crossed the old steel bridge over the Sturgeon Bay Ship Canal and parked in front of Mac’s—less a tackle shop, really, than a shrine to the culture of Great Lakes trout and salmon fishing. Getting licenses is normally a pretty cut-and-dried procedure, but when newcomers to the glories of Door County fishing showed up at Mac’s it was like pushing the “Play” button at an interactive museum exhibit. One or the other of the McMillan brothers would launch into his spiel (with a map of the peninsula taped to the counter as a visual aid) and for the next several minutes you were a captive audience. There was no stopping him and, in any event, you had no hope of getting your license until he’d finished regaling you with facts, figures, where-tos, how-tos and various nuggets of imperishable wisdom.

John, at least, saw the humor in it. “Man!” he exclaimed as we walked to our vehicles, shoving our hands into our pockets against the September chill. “You couldn’t have turned him off with a pipe wrench!”

Randy, for his part, maintained his stony silence—a silence that, as the morning wore on, was hard not to take personally. Whenever I replied to one of John’s questions about fly selection or presentation, Randy would give me a look that shot daggers, clench his jaw and stalk off to do his fishing as far away from me as he could get. I was painfully aware of my limitations, but his obvious contempt only served to make me feel smaller and more inadequate than I already did.

Yeah, he was a gem.

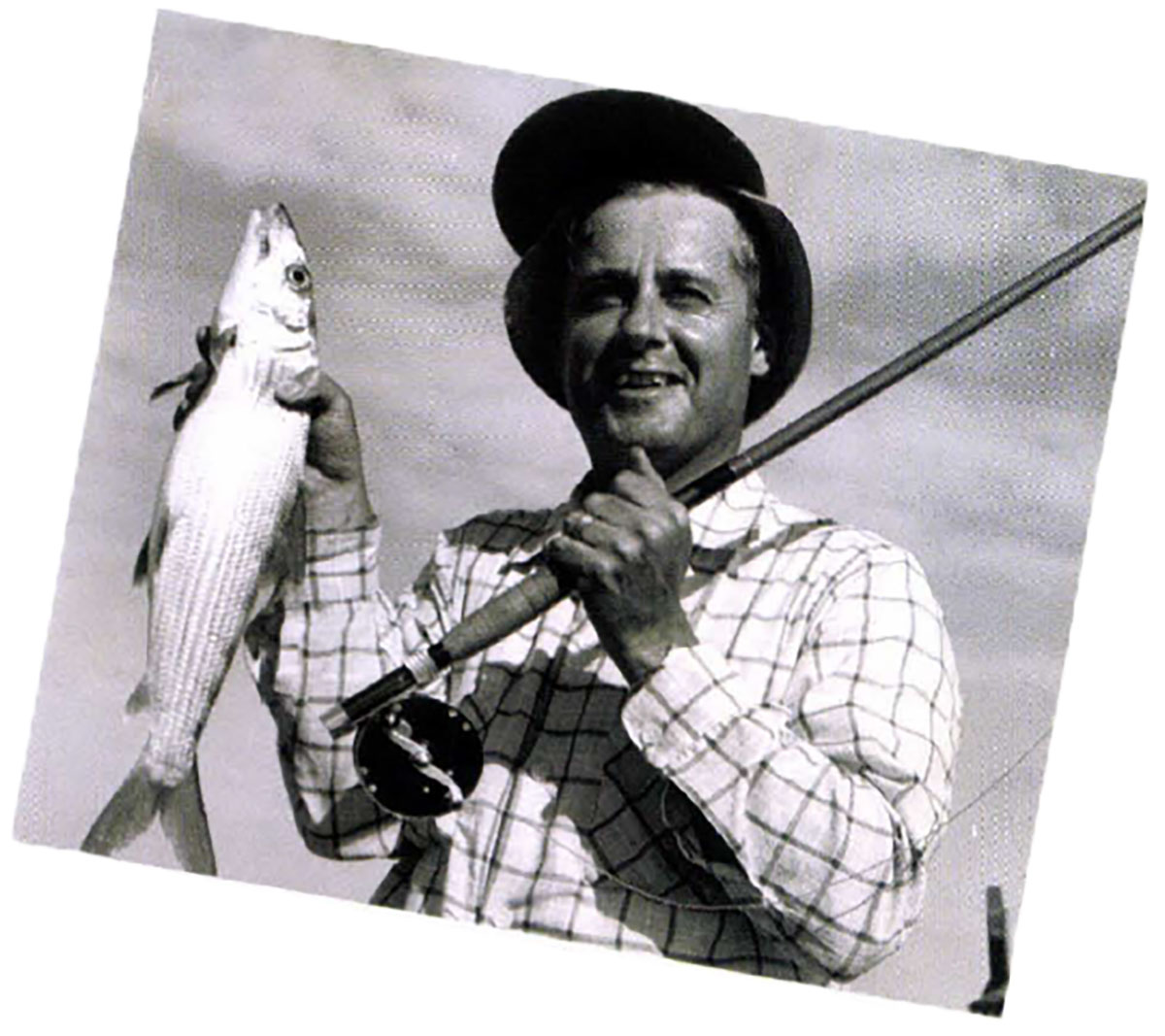

Thankfully, John proved to be as amiably enthusiastic as his partner was terminally pissed-off. He seemed to understand that I was in a tough spot, that I was doing my best and that whether they caught any fish or not there were a lot worse ways, and a lot worse places, to spend a gorgeous September morning than poking around the northern reaches of the Door Peninsula. When I showed him a pair of preposterously large steelhead holding in tiny Whitefish Bay Creek he nearly jumped out of his waders; when I showed him a brown that might have gone 15 pounds finning along in the clear, emerald-tinted water of Baileys Harbor it was if he’d been robbed of the power of speech. And when, finally, he hooked and landed a 20-pound chinook, also in Baileys Harbor, he whooped and hollered like a schoolboy whose classes have just let out for summer vacation.

Chinook salmon

He also appreciated the rustic charm of a little crossroads store, out by itself among the cherry orchards and dairy farms, where we stopped mid-morning to pick up some drinks and snacks; the kind of uniquely Wisconsin place where they make their own bratwurst and kielbasa, the owners live upstairs and the attached garage doubles as a small engine repair shop, chainsaws and snow-blowers a specialty.

We had lunch in a lighthouse-theme café with a view of Lake Michigan, dazzlingly blue in the September light, then went our separate ways. It’s possible Randy may have spoken to me, or even shaken my hand, but I tend to doubt it. I know I shook Myron’s hand because when I did, he slipped me a Benjamin—a small fortune by the standards of a guy who typically gassed up his truck in $5 increments. It was pretty good pay at the time for half-a-day’s work, but not enough to be habit-forming.

And that’s the story of my career as a fishing guide, a story that began and ended on the same day. I like to think the Alianora is still afloat and seaworthy (although I have no way of knowing that), and if I’m reading the website correctly, Myron’s son now runs the Bitter End Yacht Club, still a haven for salts, sailors and pirates of every stripe. The Palmer Johnson boatyard in Sturgeon Bay closed but, as I mentioned, the PJ name survives in Monaco. It appears to be affiliated in some fashion with Bugatti; in other words, only Arab oil sheiks and Russian oligarchs, along with the odd hedge fund manager and tech entrepreneur, need apply.

I eventually learned the name of the lodge John and Randy owned. It still exists, but damned if I’m about to put its name in print.

The White River Step-Up Fillet knife design. The razor sharp edge is then leather honed to easily slice through fish with the utmost control and ease. The new tough G10 handle creates a strong positive no slip hand purchase in wet and even slimy conditions. The step up design affords excellent visibility of blade location for precise filleting and also provides extra knuckle clearance for very thin filleting. Buy Now

The White River Step-Up Fillet knife design. The razor sharp edge is then leather honed to easily slice through fish with the utmost control and ease. The new tough G10 handle creates a strong positive no slip hand purchase in wet and even slimy conditions. The step up design affords excellent visibility of blade location for precise filleting and also provides extra knuckle clearance for very thin filleting. Buy Now