— Chapter 12 —

First Deer

The green sign with white letters read Durango, Colorado, Population 2165. I pulled our pale blue 1987 Oldsmobile station wagon with imitation wood grain siding into an open parking place outside a wood frame building – Mountain Outfitters.

We were done; all four of us were ready to take a break. We were averaging four hundred miles per day on this, our last of four family western trips. Another hundred miles still lay ahead of us this day, but we all needed to escape the car and each other for a while. My wife and Ashley, our fifteen-year-old daughter headed to a western clothing store across the hot, dusty street while John, our twelve-year-old, and I entered the manufactured cool of a large hunting and fishing outfitter. The weathered wooden facade resembled a saloon in a black-and-white western movie.

Rows of domestic- and foreign-made rifles, racks of beautifully crafted fly rods, and aisles of tents and camping gear in all colors, shapes, and sizes spread before us. We both eyed, with more than a little envy, trophy mule deer, elk, bear, moose, salmon, rainbow trout, and antelope mounts that covered the upper portion of the walls. But it was the bow section that stopped my young son and held him captive.

Before the end of the half-hour rest stop, I had purchased for John a secondhand Browning junior compound bow. I believe it was the highlight of the entire two- week trip for John. After returning home the first week in August, not a Saturday went by without John begging to go to the Totem Pole in Union, South Carolina, a small rural town, ten miles from our farm in the Piedmont section of our state.

It might be good to explain here that deer hunting was just becoming popular in the Upstate. The region had not had a deer population very long, but thanks to the Fish and Game folk’s stocking program twenty years earlier, Union County now had a respectable population. Within our group of hunting buddies, at least once a season, a nice buck would give someone bragging rights.

John and I had only recently caught the deer hunting fever. I had killed my very first buck only the year before, a respectable six-pointer. John had decided that instead of hunting deer with a rifle, he would take on the added challenge of bow hunting.

Being complete novices about this primitive hunting technique, John and I sought out the Totem Pole, a unique backyard establishment, which had the reputation of “fixing you up with all you need.” The store’s owner adjusted the bow to John’s arm and draw length and custom-made him half-a-dozen arrows with camouflage shafts and yellow and green fletching. We acquired arrow points for practicing as well as razor-sharp broadheads of the same weight that you screwed into the shaft when practice was over and the real show began.

An hour on the store’s in-house practice range gave us enough confidence to head home; John full of anticipation, me with a smile on my face at the fun my son was having.

John did not miss a day during the next six weeks without spending all his spare time with his bow. I had stacked and tied fifty new, flat corrugated boxes together to make an archery target in the basement for John’s practice. With the target placed at the farthest corner of the unfinished room and John backed up to the opposite wall, he had enough room to get off a good fifteen- yard shot. This was enough distance to rehearse for the shot he was training for once deer season opened.

During this time John and I traveled to our small farm every Sunday after church and scouted a good place to hang a stand. Luck came about two weeks before the season opened on September 15, when the two of us were walking through a hardwood drainage that encompassed our small duck pond. John was seriously looking for fresh mbs and scrapes while I enjoyed my time with him and the shower of beautiful tobacco, red, and orange fall leaves.

John’s search carried him up the steep right side of the drainage through a small group of mature white oaks and beech nees. Near the rim he hit the mother lode!

Beneath the low-hanging limbs of a spreading beech tree was the largest scrape either of us had ever seen on our land – a forty-inch irregular circle of perfectly cleared, black, loamy dirt. The mature buck that had recently passed this way had pawed the ground and swept it of all leaves. In this hardwood section of the woods with a layer of newly fallen leaves, the clear spot stood out like a neon light. Above the scrape the old buck had either chewed or torn off the tip of every branch within reach, leaving his scent to warn all lesser contenders that he intended to mate with every hot doe in these parts. Fifteen yards to the left of this spot we would hang John’s climbing stand when the big day came.

Our unusual discovery and the accumulating anticipation of the season’s opening was about to drive my son to distraction. Practice hours increased, study time took a backseat, and grades suffered. Opening weekend of bow season came and went, as did the following weekend. I could not get off work to take my young William Tell to the woods.

To his credit, John did not complain; but I knew how disappointed he was. Having to work on the first two weekends of the bow season was about to kill me. The third weekend I again had to work, this time traveling to a company trade show in Myrtle Beach, two hundred miles from our home. The show ran all day Thursday, Friday, and until lunch on Saturday. I wanted so badly to be off Saturday to take John hunting, but the likelihood of that working out looked slim.

Before leaving on Wednesday afternoon, however, I promised my twelve-year-old that I would get home as soon as I could. Maybe, just maybe, if at all possible, we could be at the farm for an hour or so before dark on Saturday.

At the end of the show Saturday morning, I took down and packed the display in the backsea t of my car and hurried up 1-26 at top speed. Close to home I found a phone booth and called John, telling him to get dressed and have all his gear ready when I pulled in the driveway. He could jump in, and we would head straight to the farm. The relief, gratitude, and excitement were evident in his words, “I’ll be ready, Dad. Thanks.”

Breaking most of South Carolina’s speed limit laws landed me in the driveway a few minutes after four. John was standing in the yard just as he had promised. We drove as fast as the Crown Victoria would travel on the two-lane tar-and-gravel road the fifteen miles to the farm.

I was still wearing my business clothes – white dress shirt, striped tie, gray slacks, and shined penny loafers when we pulled up to the barn. No matter. I grabbed John’s climbing stand out of the barn, threw it in the trunk of my Ford sedan, and drove, yes, drove, through the field of broom straw to within fifty yards of the woods’ edge where we had seen the monster scrape.

John collected his bow and arrows, and I grabbed the stand. To our delight, the scrape was clean as a whistle and no doubt just recendy freshened by Mr. Wall Hanger.

I slipped both sections of the climbing stand around a good straight hickory tree about eleven inches in diameter and helped John into the stand. I waited at the base of the tree until John had manipulated the stand up fifteen feet, turned around, secured the safety belt, and gotten settled. I passed his bow with four arrows in the quiver to him, all with new broadheads tightly screwed into the shafts. I whispered, “Good luck,” and “Be careful,” then eased the car back the quarter-mile to the barn.

By the time I parked the Crown Vic back at our rust-colored barn, the long shadows of late afternoon had almost reached John’s side of the field. It had been a beautiful fall day with temperatures climbing to the low sixties. The rolling hills and woods of the farm were now accentuated by the fading western light. My location on the ridge in the middle of the old farm, and the land’s rise from the edge of the hardwoods kept me from seeing John or anything that might cross the field in his direction.

Twelve years old, only twelve, and my son was fifteen feet off the ground, standing up in a climbing stand for the very first time, with four razor-sharp arrows, any one designed to cut the heart out of a two-hundred pound buck. I could not even see where he was from where I sat and in a handful of minutes it would be dark. What in the world was I thinking? My only consolation was, I knew there was no other place he would rather be. He loved it. John loved the outdoors. He loved it all and he got it honestly. He was growing up and I knew I had to let him go. Still I said a father’s prayer.

As I sat on the loading ramp of the barn and fretted, I confess I did not really have much expectation that any deer would approach within shooting range of John’s stand. We had been very late getting to the farm, had to drive across the fields to beat the clock, and had made a good bit of racket setting up the stand. No yearling, much less a wise mature buck, would be anywhere near that part of the farm after all that commotion. If John even got to spot a distant deer this evening, I would count it a huge blessing, but I still hoped. For John’s sake, I still hoped.

The sun slipped behind the tall pines to the west. As a chill rose off Fairforest Creek, I tried to remember if anything in my suitcase would fit over my thin cotton shirt. The long-sleeved top to my pj’s came to mind. I yanked my suitcase out from under the show displays piled in the backseat and slipped the pajama top over my shirt, necktie, and all. The thought briefly crossed my mind that my pale yellow top, tie, and dress slacks would look more than a little out of place in this setting, but who – except an old blue heron laboring overhead to roost – would ever be a witness?

Now it was every hunter’s magic moments, the twenty minutes to dark. Purple dusk oozed in and melted into night.

Unlike a rifle, a bow told no story of the hunt. I waited until the thumbnail of a new moon tipped the treetops over my son’s position before heading down in the car to pick him up. I only used the parking lights until I came close to his stand. Then I pulled the headlight knob on the dashboard, lighting up the woods with my low beams. To make John’s descent safer, I flicked on the bright high beam lights.

In their glare was my twelve-year-old, bouncing up and down in his stand and pumping both arms, bow held over his head. John’s grin seemed to cover his entire face. He was so excited, I felt sure he must have seen a deer, which would totally make his day, and mine, as well.

With the car running and lights burning, I hurried through the knee-high broom straw. He dropped me his bow and started shimmying down the tree. I noted, even before he hit the ground, only three arrows remained in the quiver – not four.

“Dad, I got him! I got him!” he whispered. “I got him! He stepped right in the scrape, and I shot him.”

“Did you hit the deer, John?”

“Yes, sir! He was standing still. I shot him right where you told me to aim. Dad, he’s big! He’s really big!”

“Which way did he go?” I glanced over John’s head, searching the area where tire car lights fell.

“He went straight down the hill and out into the backwater, Dad. I could hear water splashing for a second or two. Then it all got quiet. He may have made it to the duck pond.”

Much darker now, neither moonlight nor starlight would reach the floor of the swamp. We were totally unprepared for this scenario.

I thought for a second then said, “Let’s ride back up to the barn and get the gas lantern.”

We rode the short distance back up to the barn, then unlocked and rolled up the heavy door. I pulled the lantern from its hook on the wall, dusted it off, adjusted the gas, and lit the mantle with one of the big kitchen matches I kept in a glass jar. The lantern hissed to life. Assured the lantern had survived the hot summer months in good shape, I turned it off, grabbed a couple extra matches, and returned to the car.

An old logging road took us close to the deer’s last position. When I reached where the little-used dirt road that crossed the head of the duck pond, I stopped, leaving the engine running and the lights on. After relighting the lantern and adjusting the flame to its brightest, John and I eased off the road into the head of the low, damp ground leading toward the headwaters of the pond.

Two dioughts crossed my mind: assuming he had made as good a shot as he had said, I must find John’s deer, after all it was his very first.

And My dress clothes were going to get really wet and really muddy.

John moved out far to the right as the lantern beam spread, while I moved direcdy into the swamp. I held the Coleman lantern as high as I could so as to see past its bright beam. Wherever a small tuft of grass grew, I tried to step on that, knowing this would be higher ground than the wet, muddy spots. No matter. In minutes water had thoroughly soaked my shoes, socks, and britches legs. I could hear John splashing along ahead of me, oblivious to the fact that I was not protected by hand-me-down 18-inch L.L. Bean rubber boots, as he was.

When I reached the point where the light touched deeper backwater, I grew a little worried. Either John or I should have cut the deer’s trail. Neither of us had seen blood or fresh tracks.

“John, you see anything?” I called out.

“No, Dad, nothing yet.”

“Do you think he made it this far?”

“I don’t know. I heard him splashing through water. But then all noise stopped, and I couldn’t hear anything.”

“Let’s go back the way we came and move closer to the base of the hill. We’ll make another pass.”

“Okay, Dad,” I heard from the fringe of light.

As I turned to head back myself, I stopped when a glint of reflected light caught my eye. What looked like just the base of a small sapling held my attention. I realized it was the curved antler of John’s buck with its head lying on its side. John’s prize was a buck, alright. A nice one from the look of it.

“John, I’ve got him spotted! He’s between us. Start walking toward my voice.”

The splashing of John’s boots stopped suddenly. His excited voice called out, “I see him, Dad! I see him! He’s lying in the muddy water.”

The two of us reached the old rascal at the same time. We just stood there for a moment, looking at what was obviously a mature eight-pointer.

John eased to the ground and ran his hand all the way down the deer’s side, patting him along the smooth mixture of brown and gray. The arrow, ha If broken, had sliced the deer’s heart in two. The bruiser was dead on its feet but had powered through fifty yards before piling up.

“Great shot, son. Very clean. He’s a very nice buck,” I said.

We each grabbed one side of his antlers and started toward the car. Dragging the deer through the muck was tough going. The mud sucked a loafer right off my foot at one point, but after locating it, I slapped it back on and sloshed on toward the road.

Now what were we going to do?

“John, I don’t think we have any choice but to put the deer into the trunk. That’s the only place big enough to carry him to the processor. I don’t know of another way to get him there. You stay here with the lantern and deer while I drive back up to the barn. I’ll find something to lay him on. We’ll ruin the car if we don’t.”

At the barn I found an old 10 foot x 10 foot tan canvas tarp, which I spread out, being sure to turn up all the edges to keep mud and blood off the carpet. I hurriedly drove back to my son and the deer.

Lifting the heavy deer up and over the edge of the bumper was like lifting jelly. As soon as we got one end in the trunk and then tried to push in the other end, the whole deer would flop out on the ground. After a few unsuccessful tries, I got in the trunk myself. I thought that if John could manage to lift one of the deer’s front legs, maybe I could pull the rest of the deer up. After climbing in, I leaned out as far as possible while John struggled to hoist one of the deer’s legs up to me. After several exhausting tries, I was able to snatch one foot as John lifted with all his might. I could do no more, though, than get the front half of the deer over the edge.

“John, you’re going to have to climb in the trunk, too, so that we can both pull.”

I held onto the front legs as John scrambled in with me. Once inside, John got the left leg, I got the right, and we hauled back on the deer until the anders scraped the bumper and the bulk of the deer reached the tipping point. He fell in the trunk on top of us. We were both a mess – covered in mud and blood – but at least the deer was loaded.

Once out of the trunk, we took a long look at John’s kill lying there in the lantern’s glow. I was so proud of my son’s accomplishment. The smile on my twelve-year-old’s face was worth everything.

I said “Let’s get him over to Lancaster’s. We need to get there before they fill up the cooler.”

After a few more moments admiring the kill, we backed out of the swamp road and turned into Lancaster’s Deer Processing shed fifteen minutes later.

I pulled the car up the gravel drive at Lancaster’s, put it in reverse, and backed slowly toward the skinning hoist as several small groups of hunters moved aside. Every observer, I am sure, had his own thoughts about these obvious newcomers, in a car, no less. I stopped just short of the skinning rack. John piled out on his side as I popped the lid of the trunk.

Several small does and a young four-point buck already lay on the ground ready to be cleaned. A decent-size buck – a two- year-old six-point – already hung on the hoist.

Still in my muddy business clothes, including my yellow pajama top that I had completely forgotten about, I joined my son. The curious group of seasoned camouflaged hunters all gathered to see what in the world was in the trunk of my car.

John’s four-year-old buck was undisputedly the best kill that had been brought in that week. Getting the deer out of the trunk was no trouble. All the other hunters pitched in and helped. Weighing the buck on the scales was now top priority for us and those seasoned hunters. The needle on the big brass spring scales setded at one-ninety. All the older men congratulated John. They knew a real wall hanger when they saw it.

Some patted him on the back. Others said, “Nice deer, son.” and others “Great job, young man.”

Craig Lancaster, owner of the skinning shed, told John, “I clean a lot of deer in a season. Not many grown men kill a buck that big.”

I was one proud dad!

When we finally reached home, I slipped into the bedroom and phoned Craig. I told him to please cape out John’s trophy buck and I would have it mounted as a surprise.

I thought, What a great Christmas present – my twelve-year-old bow hunter’s first deer.

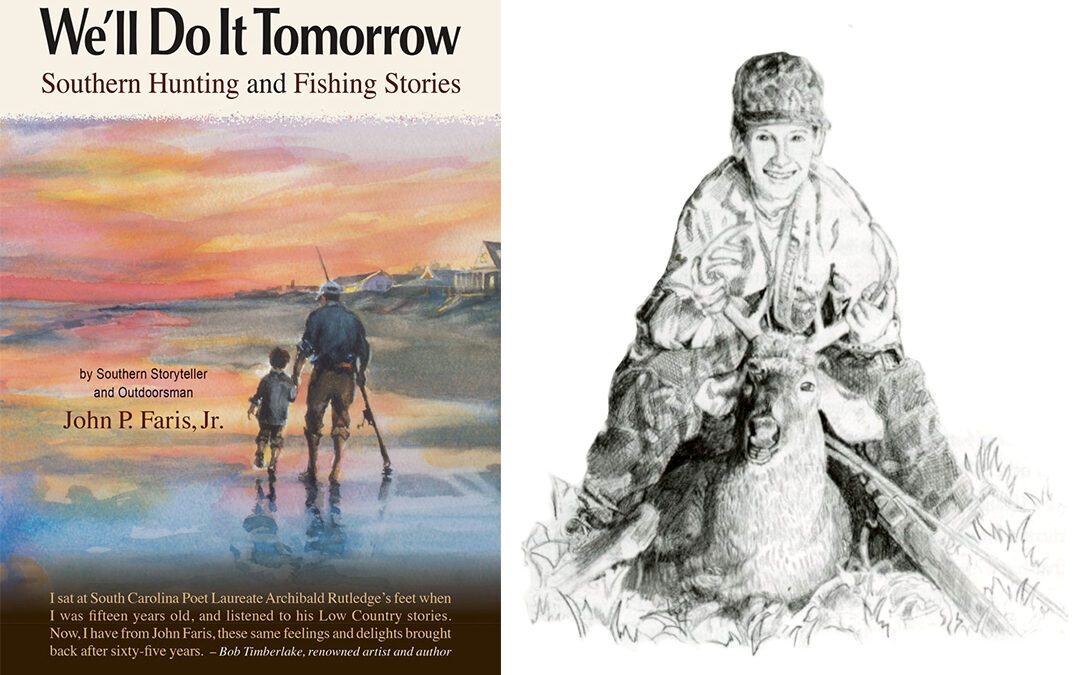

We’ll Do It Tomorrow

We’ll Do It Tomorrow

Click Here to Buy Now

We’ll Do It Tomorrow is more than a book of tales about hunting and fishing, these stories are about the joys and sorrows of life. They will linger in your heart and leave you wishing for more. Filled with 15 stories and 30 illustrations We’ll Do It Tomorrow is definitely a keeper.