Using only simple tools, Italy’s Firmo Fracassi achieves astonishing detail in his bulino-style engravings.

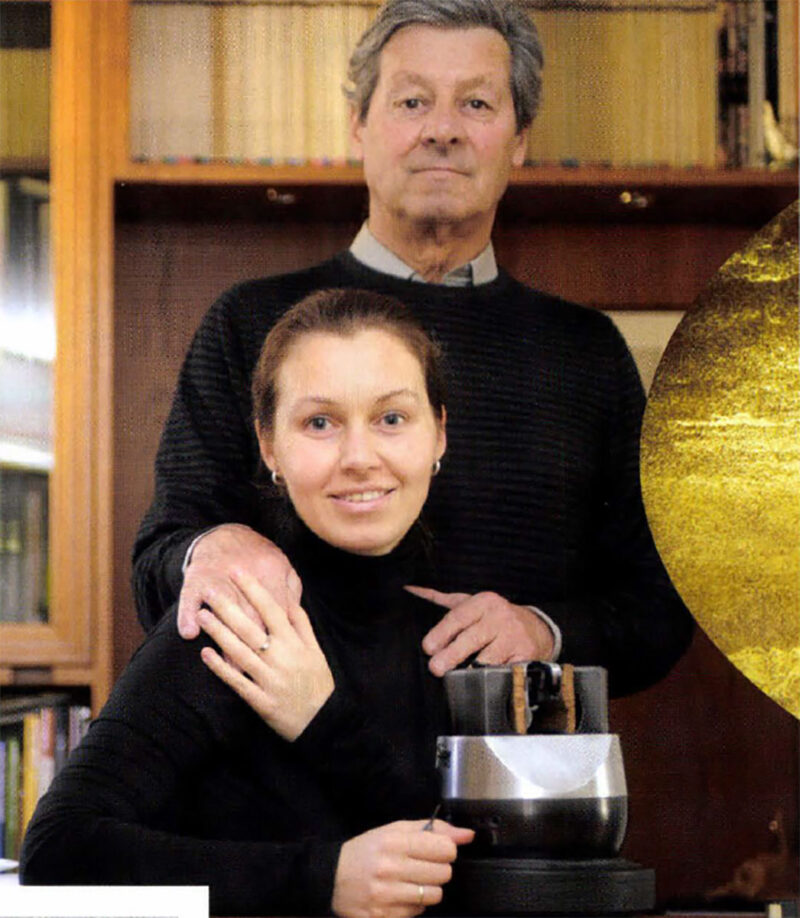

Firmo and daughter, Francesca, who has been engraving for decades under the tutelage of her father.

If suffering is a muse for artistic genius, it came early in the life of Firmo Fracassi.

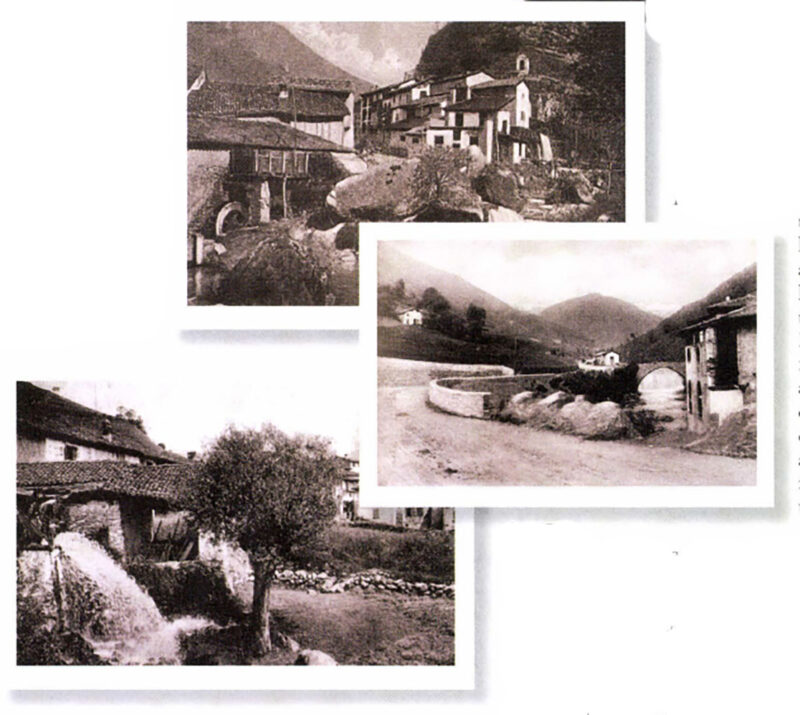

Born in 1939 in Tavernole, a village nestled in Italy’s alpine hills north of Brescia, Fracassi was only a boy when the Nazis occupied his town. They enslaved its inhabitants, forced them to build arms for their war effort and treated them savagely in retribution for their partisan attacks.

“Living through the war years was a terrible hardship with unspeakable moments,” Fracassi writes in Firmo & Francesca Fracassi — Master Engravers, a definitive book that chronicles the life and works of Italy’s greatest living bulino engraver. One of those unspeakable moments occurred when German troops attempted to murder Fracassi and his family by throwing grenades into their home.

“Firmo still has scars and shrapnel in his arms,” says Stephen Lamboy, who along with wife Elena Micheli-Lamboy co-authored the Fracassi book. “He showed me this before his wife Maria interceded and begged me not to go any further as he cannot bear to speak of it.”

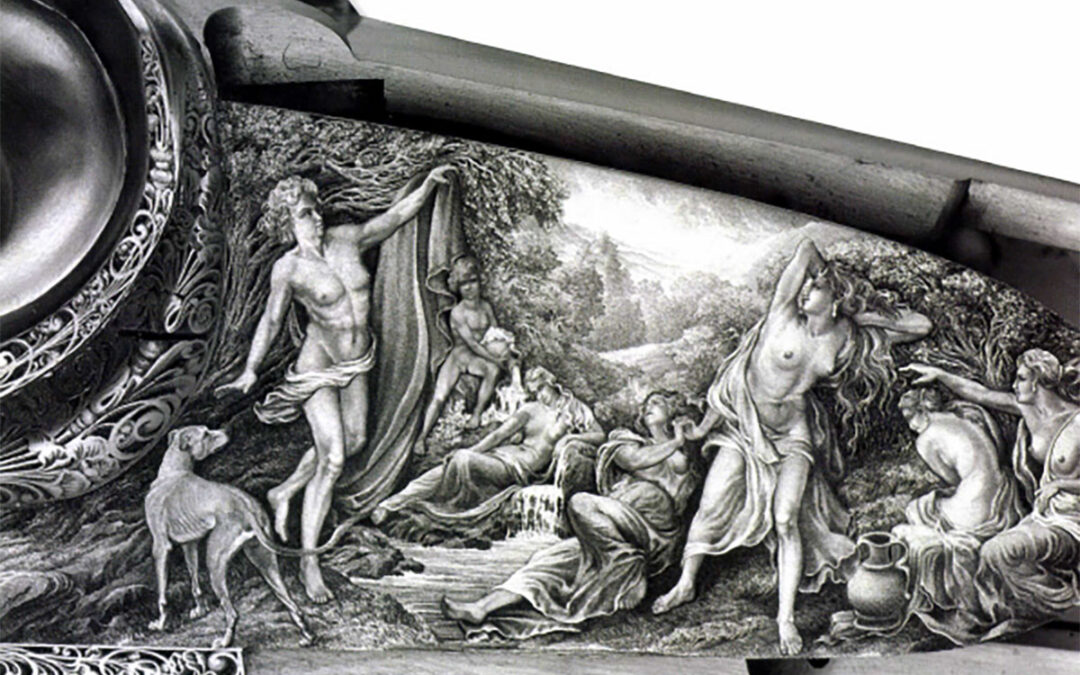

Firmo Fracassi dedicated this magnificent bulino engraving to Diana, Goddess of the Hunt. Note his use of fine, deep liberty scroll to frame the work. All elements, from the grass and trees to the hills and sky, are masterfully lit and depicted to intensify the drama on this engraving for a F.lli Rizzini side-by-side.

As Fracassi notes in the book’s introduction: “I am who I am because I lived through the darkness of those times.”

For solace, the young man took refuge in nature and in his art. “Drawing and studying art saved his sanity,” Stephen Lamboy explains. “He showed me an early charcoal and pen drawing of the graveyard in Tavernole; it was the most dark and depressing drawing I have ever seen; it took away all joy instantly. He may have had to escape into the creation of millions of dots to surmount those memories… .”

Millions of dots aptly describe the bulino engraving technique that Fracassi pioneered a half century ago. Bulino, which in Italian means graver (or burin), is a sharp, hand-held tool used to cut dots and lines in the surface of metal.

By varying the pressure on a burin to change the size and depth of the cuts, an engraver can influence how light interacts with the metal: the more dots and lines and the deeper they are the darker the shading; those shallower and farther apart will produce lighter tones.

In a Fracassi engraving, those dots and lines — individually infinitesimal in size — literally number in the millions. His mastery of the technique, along with his innate ability as an artist, has allowed him to create scenes of transcendent beauty. His detailed, photorealistic compositions are suffused with complex interactions of darkness and light and are conceived to invoke intense reactions in the viewer.

These old photos are of Tavernole, Italy, which came under German occupation during World War” – “a time of terrible hardship,” Firmo says.

Today, engravers the world over practice bulino — with varying degrees of skill _ but as a technique of gun embellishment it hardly existed when Fracassi apprenticed at age 12. Italian engravers back then were skilled enough, but they mostly reproduced standard scroll and floral patterns over and over. Naturally precocious, Fracassi soon mastered his trade’s traditional tools — the hammer and chisel — becoming an independent engraver at 16. He tired quickly, however, of repetitive production engraving.

Instead, Renaissance Art inspired him — the engravings of Albrecht Durer and Hendrick Goltzius; Michelangelo’s reproduction of the human form; the drama and emotion of Caravaggio. Caravaggio, in particular, was a master of chiaroscuro — a painting technique that uses light and shadow to create mood in a work and emotion in the viewer.

While Fracassi made his livelihood engraving rote patterns for the trade in the 1950s and ’60s, he used “every spare minute” to practice with his burin the lessons he learned from studying Renaissance masters and from his drawings.

His breakthrough came in the early 1970s when he caught the eye of Mario Abbiatico, who as co-founder of gunmaker Abbiatico & Salvinelli (FAMARS) was then leading a revival of Italian gun making. Buoyed by unprecedented commissions from Joe Bojalad, an American collector keen on creating high-art guns, Abbiatico cut Fracassi loose to experiment.

“For the first time in my life,” Fracassi remembers, “I was free to leave hammer and chisel behind and use a bulino.”

Engraving since has never been the same.

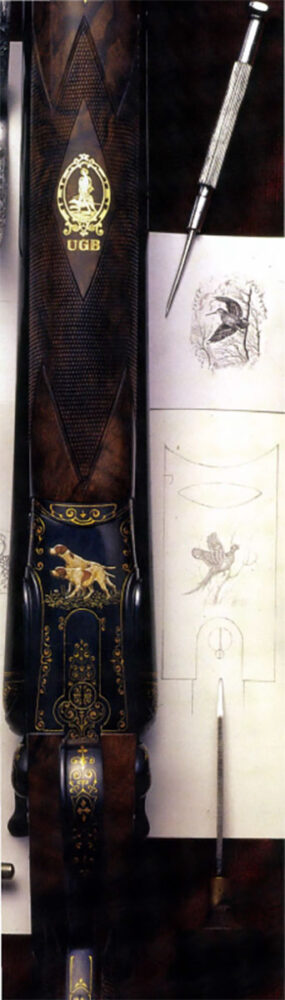

Fracassi combined steel and gold to create high

drama on a 2 1/2-inch belt buckle. In describing this scene, the artist wrote: “My work is all about volume, light and perspective.” This enlargement of a 7 -inch watchcase in white gold reflects the mind-boggling detail Fracassi can achieve with the bulino technique.

It was a rainy cold day in March 2005 when wife and I, along with Elena Micheli, visited Fracassi at his home, a two-story flat in Sarezzo, near Brescia. Fracassi appeared nothing like the tempestuous artist I had half expected. Fit and impeccably groomed, with brown eyes and a dimple in a well-formed chin, he was reserved but not grave, serious but polite and hospitable, and generous with his time.

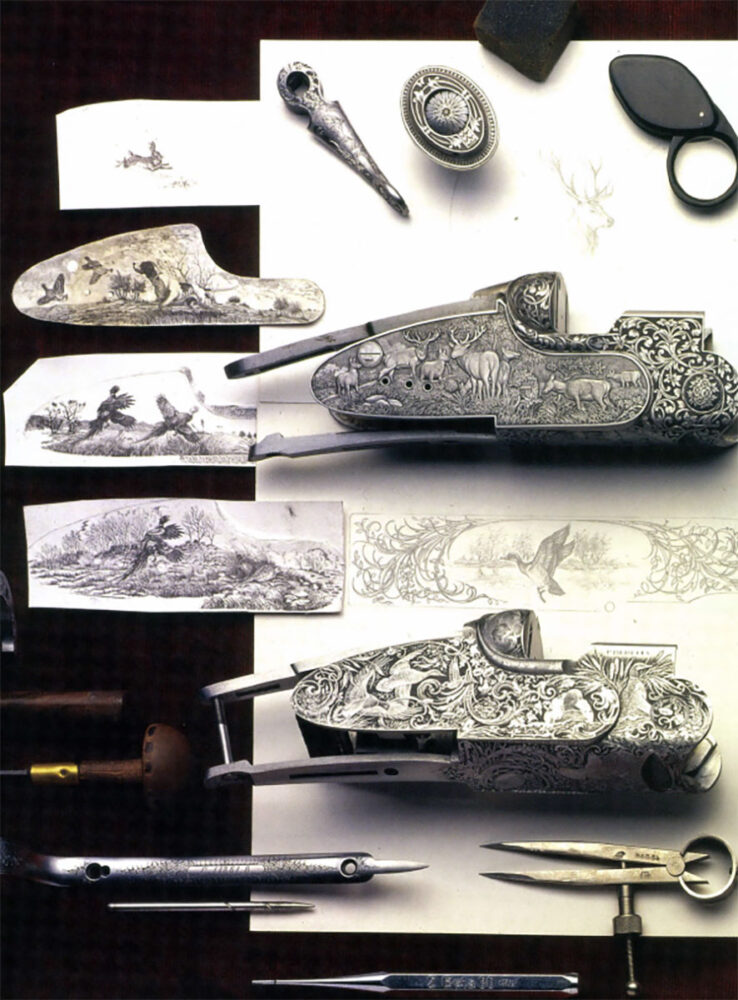

After small talk and coffee, he led us upstairs to the studio, a neatly furnished room where two ball vises rested on a ledge under a north-facing window. Beside each vise — one for him, the other for daughter Francesca — were a couple of gravers, a loupe and a sharpening stone or two.

He works over his vise, peering through a 10x loupe held in his left hand, burin cupped in the palm of the other.

“The sound of him working is very, very quiet,” says Stephen Lamboy, “only a muffled tick, tick, tick — very disciplined.”

Stateside, where the use of microscopes and high-tech air-driven power-gravers is ubiquitous, American engravers often marvel at Fracassi’s achievements using only “simple” tools.

Stateside, where the use of microscopes and high-tech air-driven power-gravers is ubiquitous, American engravers often marvel at Fracassi’s achievements using only “simple” tools.

Simple tools maybe, but Fracassi imagined sophisticated, novel ways to use them. By experimenting with graver geometry, he learned to sharpen his boons at more acute angles than had previously been done, permitting him to engrave dots and lines smaller than a pinprick. His cuts are so small and precise that they can number in the hundreds of dots per millimeter.

This density produces images that appear not only three-dimensional in shading and texture, but also look almost alive. Astonishingly, the realism rendered not only survives high magnification, it actually improves under it.

“The amount of detail he can delicately cut into metal using his unique bulino style defies the imagination,” notes Blue Book Publications’ S.P. Fjestad, a student of engraving and the editor/publisher of the Fracassi book.

Adds Stephen Lamboy: “No detail in a composition is unimportant, and all get infinite attention.”

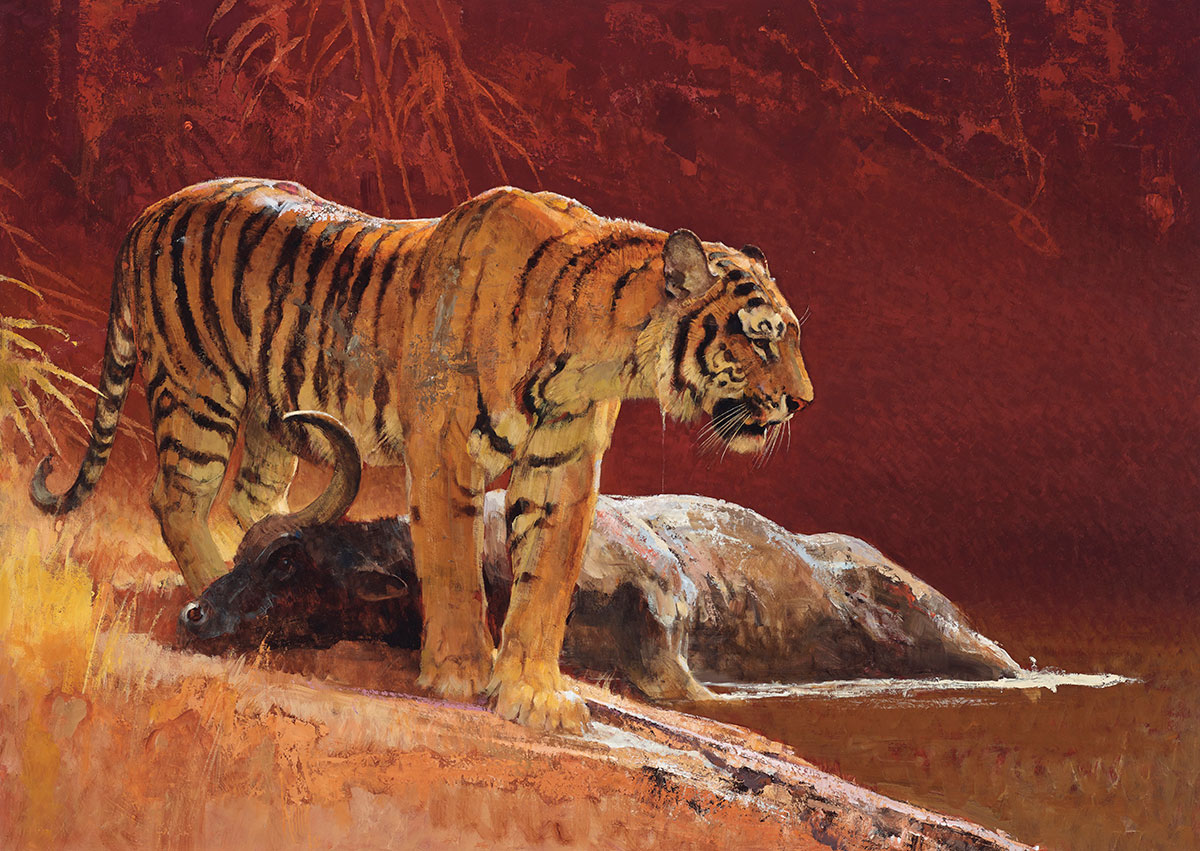

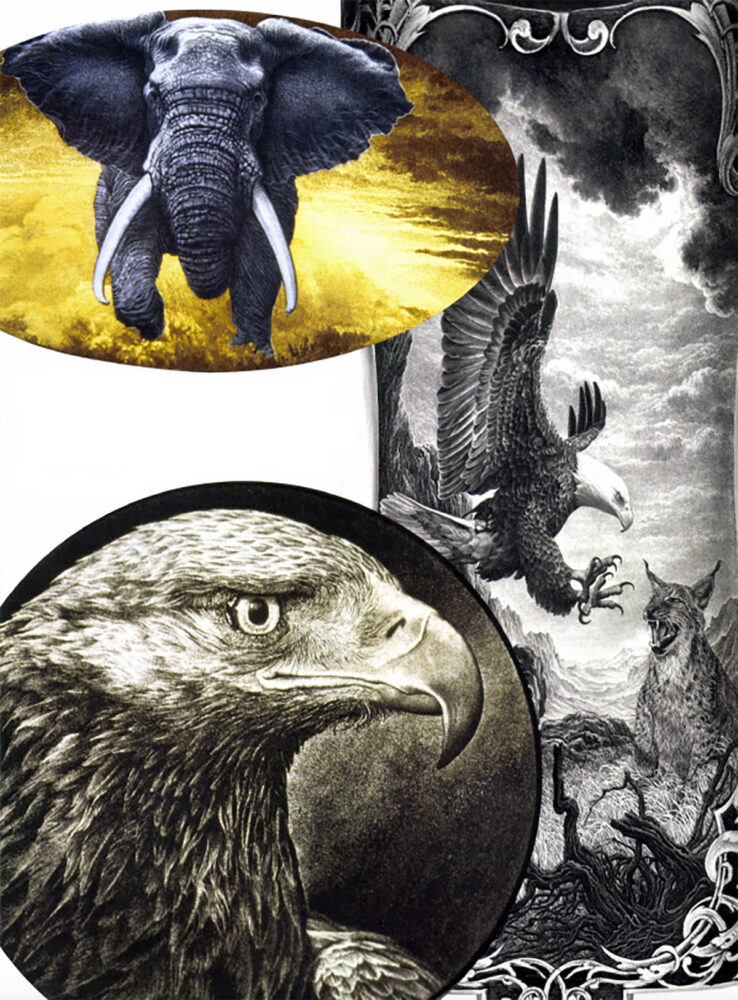

This riveting game scene by Firma Fracassi now adorns a Calazan over-and-under. Francesca Fracassi surrounded these swans by an explosion of tiny water droplets. Firmo composed these bulino portraits of African dangerous game for a set of Fabbri knives.

The other principle quality — and perhaps the most distinctive — is Fracassi’s brilliance in capturing chiaroscuro in steel. A recurring motif in his engraving is not merely the interplay of light and dark, but the Manichean battle between them, with the rays of the sun eventually prevailing.

As Lamboy describes one engraving: “It is as if the light of hope eternal is coming to the struggle.”

Some of my favorites are Fracassi ‘s winter scenes, where gamebirds fly over snow-bound landscapes and white tones — the most difficult to reproduce in steel — predominate. Their crystalline purity suggests peace and tranquility, and in them it is not hard to imagine that Fracassi has at last conquered the terrors of war that clouded his childhood.

Fracassi’s greatest talent, ultimately, is his uncompromising vision of himself as an artist and his singular talent for expressing that vision in the unforgiving medium of metal. “To be a great engraver you must first be a great drawer,” he explains. “One simply cannot exist without the other.”

Before beginning a job, Fracassi may spend weeks, even months, researching the subject at hand and then working out the composition of its elements in his head. Only then will he go to his graver and vise.

Fracassi admits he gets irked if a client asks him for a drawing of an engraving. “If I had to draw it on paper first, then it would be the piece of art,” he says. “To engrave that would only repeat what I have already created, and I would not enjoy that.”

A full-blown commission can take him thousands of hours to complete, depending on its size and complexity. In the past, when Fracassi was “hungrier,” he’d toil 12 hours a day; nowadays he works seven or eight. Given roughly 2,000 working hours in a year, patience is a virtue that each potential patron must possess.

And the cost of a commission? Answer: “Fracassi absolutely won’t discuss what he charges,” says Fjestad. “Other master Italian engravers are tightlipped about pricing. Part of their sizzle is not knowing what they charge.”

And the cost of a commission? Answer: “Fracassi absolutely won’t discuss what he charges,” says Fjestad. “Other master Italian engravers are tightlipped about pricing. Part of their sizzle is not knowing what they charge.”

Since specializing in bulino in the 1970s, Fracassi has engraved only 57 guns, and a smattering of knives and other objets d’art. A family man, he rarely socializes with other engravers, and apart from his love of biking in the mountains, leads a life almost monastic in its dedication to his art.

“When I go to bed in the evening,” he says, “I look forward to working in the morning.”

He has inspired almost all his peers in Italy and abroad, as well as legions of younger engravers who have come after.

“Fracassi’s influence on engraving cannot be overstated,” says Winston Churchill, a superb artist in his own light and a man who is widely regarded as America’s best engraver. “He is the Michelangelo of this era … he has set the gold standard for engravers of this generation, and maybe for all times.”

Though many have tried to copy his work (to Fracassi’s great distress), his inimitable style has never been truly duplicated — with one exception: by daughter Francesca, who works by his side.

Though many have tried to copy his work (to Fracassi’s great distress), his inimitable style has never been truly duplicated — with one exception: by daughter Francesca, who works by his side.

Only 36, Francesca has engraved for almost half her life, tutored by her father, a teacher she describes as “extremely patient but also demanding from the beginning. As a young woman and artist, it was difficult to accept my father’s fastidiousness and maniacal requests for precision, but I had so much to learn from him.”

That she learned those lessons well, however, is not in question. Even to the most expert eyes, her work is essentially indistinguishable from her father’s. Today they often collaborate on a project, with daughter tackling the scroll and shading that frames father’s game scenes.

Francesca arrived during our visit and unveiled a sidelock over/under she alone was engraving with scenes of swans landing in a spray of water in an icy pond. Time seemed frozen — drops of water hung in the sky, a pair of wings pushed off the lockplate, their feathers backlit by sunlight penetrating a screen of darkening clouds. It was a breathtaking display of art that, frankly, overshadowed even the superb craftsmanship of the gun it embellished.

And in this sense, father and daughter Fracassi share a common vision for the future of engraving. “We dream of a new canvas which goes beyond the gun where we can create a composition without limits,” they note in the book dedicated to their art. “We dream of engraving large plates worthy of exhibiting in the world’s best museums and appreciated as fine art. This is the next breakthrough.”

Author’s Note: Special thanks to co-authors Stephen and Elena Michelli-Lamboy, and S.P. Fjestad for assisting with this article and for permission to quote from Firmo & Francesca Fracassi – Master Engravers.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the August 2011 issue of Sporting Classics.

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes, and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case. Buy Now

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain, and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes, and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case. Buy Now