A subspecies of zebra went extinct in the 19th century, leaving the Dark Continent without one of its South African herd animals. Now, after more than 100 years, the “quagga” is back. Sort of.

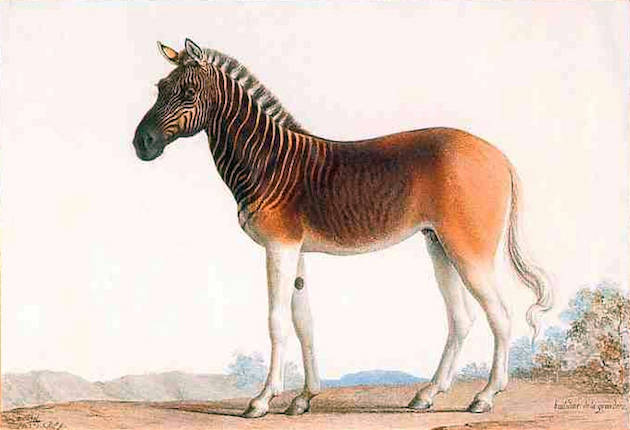

The quagga was once thought to be a distinct species, but DNA analyses have since proven it to be a subspecies of the plains zebra. It had stripes like its cousin, but only on the front half of its body. Its haunches and trunk were brown instead of white like a typical zebra. According to CNN, vast herds once roamed across the southern tip of Africa. Europeans, particularly the Dutch, hunted the animals because they competed with livestock for grazing. The last quagga reportedly died in 1883 in Amsterdam.

The quagga was the first extinct animal to have its DNA examined. While nothing extinct can ever truly be brought back into existence, researchers with the Quagga Project hypothesized that the quagga’s genetic information might still exist in the DNA of its plains cousin. Testing of the plains zebra’s skin showed the animals could be selectively bred for a quagga’s outward appearance, with subsequent generations showing a greater similarity to their extinct relatives.

“The progress of the project has in fact followed that prediction. And in fact we have over the course of four, five generations seen a progressive reduction in striping, and lately an increase in the brown background color showing that our original idea was in fact correct,” said Eric Harley, a Cape Town University professor and leader of the Quagga Project.

Critics have labeled the project a stunt, with the “return” of quaggas a shallow attempt at environmental reparations. Even Quagga Project member Mike Gregor said the replacement animals “might not be genetically the same,” and, “there might have been other genetic characteristics [and] adaptations that we haven’t taken into account.”

Rather than say the animals are true quaggas, the scientists have named their results “Rau quaggas,” after one of the project’s originators, Reinhold Rau. Of the 100 animals in the project’s breeding program, only six hold that name; when that number reaches 50, the project members hope to place the Rau quaggas in their own preserve to live as a herd.

“What we’re saying is you can try and do something or you could just not,” Gregor said in defense of the project and its ambitions. “And I think us trying to do, trying to remedy something, is better than doing nothing at all.”

“If we can retrieve the animals or retrieve at least the appearance of the quagga,” Harley said, “then we can say we’ve righted a wrong.”

What say you? Does a genetically/physically similar animal qualify as raising an extinct species from the dead?

Seems to me that the project is worthy of the effort. Man has a long history of excess and “hunting” animal to extinction. To steal and modify a movie line, “That ain’t hunting, that’s killing.” We should be grateful for the opportunity to replace some of those animals for whose demise we are responsible…passenger pigeon, ivorybilled woodpeckers?