I’ve always had a few BB guns around the house, but now there’s a whole lot more, and I’m hungrily riding happy trails looking for the rest.

I suppose if you’re going to revert to childhood, you might as well just get on with it, whole hog and all the daisies.

My grandpap believed so. About the time he gave me then the thing I’m trying to find back now, he advised, “Boy, if you’re bound to do somethin’, don’t talk about it and fret over it like most people do until it’s too late and gone. Just go the hell on and do it.

“When you git as old as I am—’less maybe you’re in servitude for a Purdey shotgun—you’ll find that over time ever’thing works out in the wash anyhow. A pig here, a poke there.

“Don’t be afraid to do somethin’ while you’re here, when maybe you’d think you shouldn’a when you’re gone. ’Speci’lly if it seems foolish to somebody else at the time.”

Well, I’ve lived nigh as long as he did about now, and I’ve found that to be a pretty profitable philosophy. In sentimental accrual for sure, and not an altogether shabby proposition when it comes to fiduciary gain.

Because I’ve found most every time, with every heart’s desire I embrace, there’s a host of other folks out there wanting to do the same.

Which is why I’ve reinvested about three grand the past two months or so in yesterday. I know, most folks invest about everything at this stage of life in tomorrow, and maybe that’s more frugal and perceptive, but hell, it’s all just numbers on a page. Grandpap was right. What counts more is what’s on the ledgers of your heart before the ink dries. While you’re still here to enjoy it.

When it comes to the final accounting, whoever’s left can bargain off the necessities to pay for the planting, then notion out the interest on the frivolities to someone still here who wants yesterday, too.

When you can buy yesterday, or at least the remnants of yesterday, use them until tomorrow comes, then pass them on to somebody else who’s invested in yesterday, it strikes me the whole world’s happier.

I’ve been happier than a weevil in a cotton boll buying back BB guns.

Daisys? “Oh, yeah. Gotta be a Daisy, pod’ner.” Red Ryders? “Yep. And 1894s.”

You know one of the happiest things about BB guns—well, Red Ryders particularly—for us old farts that came up in the late ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s? We were there, pod’ner. Seen it all. Had it when it was happening. Lived it ’fore the ink dried.

Went to the Saturday afternoon serials at the picture show, came home, grabbed our trusty Red Ryders, set off huntin’, capturin’ outlaws, and warding off Injuns. Killed a bunch o’ Luck’s pinto bean cans, picked off bumblebees on the fly, shot wasps on watermelon rinds, rounded up the worst of the desperados. Made the neighborhood safe again. Right there ’longside Bob Steele, Johnny Mack Brown, Roy Rogers, Lash LaRue and Gabby Hayes.

A lot of us lived East, but with our Ryders and a Daisy Peacemaker, we all went West.

We lived it until it was part of us. Especially that little 36-inch lever-action saddle gun. And it’s never left. At this point we’ve had the Purdeys and the Hollands, the McKay Browns, the Parkers, the Famars, the Piottis, and the Guerinis. And still, I’ll just about bet my favorite Stetson and chaps that somewhere in a corner of the house—probably a pretty handy one—there’s a Red Ryder BB gun. Old or new. To maintain respect among the varmints at the bird feeder, the black snake in the hen’s nest, or the vermin in the corn crib. It was, and is, the original gun no man ever outgrows.

I’m convinced, had there been an eighth day in the week, God would have used it to create the Red Ryder.

I know, there’s a few folks rode shy of the sagebrush and favored the old Daisy 25s—the pump guns. They shot strong, and were pretty desirable for that reason alone. Plus, for a time Daisy overlaid some gold-stenciled hunting scenes on the receiver, like a hunter and pheasants, and a dog and some ducks. I mean, a fully “engraved” gun when you were 9 years old was no easy thing to turn aside. But gold-gilding or no, I never saw Hopalong Cassidy carry no pump gun, nor, come riding time, Randolph Scott or Jimmy Stewart shove less than a Winchester ’73 in the scabbard.

If you were Have Gun, Will Travel, friend, you backed those holster guns up with a lever gun, a bonafide saddle rifle.

Though, by the way, did you know that the Daisy 25 has a strong tie back to D.M. Lefever, and the fine, old Lefever Arms Company guns, the lovely old Syracuse sidelocks? Sure does. Its genesis, in fact.

In December of 1911 Charles F. (Fred) Lefever, son of the late D.M. Lefever and one of the siblings in the old D.M. Lefever & Sons Company, approached Daisy by letter with his newly invented pump gun. Wrote, “Come to St. Louis, and I’ll show it to you.”

In other words, Mister Mountain, come to Mohammed.

Lefever was a cantankerous sort, and when Daisy at first reflected reticence, he quickly returned, “Well, if Daisy ain’t interested, others will be.”

With that, E.C. Hough, the Daisy principal—at first offended—decided to reconsider and set off for St. Louis, ending up bringing both the man and his gun back. Thus the Model 25 pump of 1914, which by the time it was discontinued in 1979 had sold more than eight million.

I was talking with Lefever’s grandson at the recent Side-by-Side Spring Classic, and we both got a kick out of his recollection that during the 41 years his grandsire was at Daisy, he was said “to have quit about once a year.” Maybe so, but what the hell would the world do without those we sometimes chide, who are as equally gifted with genius as eccentricity?

But for all the success of the Lefever Model 25, and the company’s Buck Rodgers and Buzz Barton hero-guns of the ’30s, it was the wooden-stocked, #111 Model 40, introduced in 1940 and based on the Fred Harmon comic book character, Red Ryder, that validated beyond all expectations and for all time the 1895 evolution of the old Iron Windmill Company of Plymouth, Michigan, into Daisy Manufacturing and BB guns. Largely due to the cult following it generated among a simultaneously imaginative and wildly receptive, vintage generation head over heels in love with Western romance.

Actually a dressed-up version of 1939’s popular “Lightning Loader” Carbine, the 111-40 was initially touted with unrivaled aplomb in an April 1940 preview ad in the perennial Daisy spot on the back page of Boy’s Life: “Watch for Red Ryder. Coming next month.”

At its debut, for which Daisy bought the whole back page, the pitch was virtually irresistible: “Out of the Golden West, Red Ryder brings You this Sensational new 1000-shot Golden-Banded Daisy. Picture Yourself riding the range with This lashed to your saddle. Looks real, and shoots with a snarley carbine Bark. Rush down now to your nearest hardware store.”

Mom ’n’ Dad, dig out the egg money. It sold for $2.95.

Probably most of us gray enough to remember first slavered over the lever-action Red Ryder Carbine—with saddle ring and leather thong, the man himself, his horse “Thunder,” and lariat-encircled signature burned into the stock—around 1946-’47, upon its reintroduction roughly three years after Daisy’s mid-’42 production suspension for World War II.

From there—along with a stick horse, hat, vest, chaps, revolver, boots and saddle—it was a cowboy, bust-a-gut, gotta-have staple of ’40s/’50s boyhood America. Hell, it was America. Suddenly we could all own a Winchester, “The Gun That Won the West,” and ride the range carrying the closest thing to a Win. 94, a real gun that shot real bullets—of which we were warned: “Be careful, now, or you’ll shoot yer eye out, kid.” And Pilgrim, I’m here to tell you, that was BIG!

Warrants were immediately served on outlaws, low-down, thieving scalawags, bullfrogs, alley cats, water spiders, rats, cat-birds, big game like squirrels and chicken snakes and everything between, and by 1949, the 111-40 had become so popular that one million guns were sold in a single year, a sales figure theretofore unheard of. Plus, in the late ’40s, ammo was cheap. You could buy penny packs of BBs, torn off a roll of cellophane segments, as many as you could afford with paper-route money.

The 111-40 remained in the Daisy line until 1957, selling six million. Somewhat incredibly, then, the name Red Ryder was dropped.

Only to be brought back by Daisy in 1972.

So that even today, most happily, the venerable old Red Ryder Model 40—reconfigured only slightly in 1979 as the Model 1938B—rides on. The most famously recognizable BB gun ever, and probably the most highly sought by collectors, the early guns now in especially good condition easily reach the $200 mark and beyond. Moreover, an amazing number of special, limited-edition and commemorative Red Ryder guns have been produced by Daisy over the years, including the 50th, 60th, 65th, 70th, 75th, Millenium, 120th and now 130th Anniversary Models, DU editions, “A Christmas Dream” edition from the 1980s’ Little Ralphie movie, A Christmas Story, a Roy Rogers & Trigger Commemorative and numerous others, such as the “Pledge of Allegiance” and “Second Amendment” guns.

I never knew there were so many. I’ve always had a few BB guns around the house, but now there’s a whole lot more, and I’m hungrily riding happy trails looking for the rest. I’m astounded to no end at the plethora of other Daisy BB and pellet models and variants aside from the Red Ryder—almost 400 and counting—the company has made over the 130 years of its existence.

A Safari Model, for instance, #86/70, quite rare and made for only the six years from about ’70 to ’76. Hardly recognizable in design as an African dangerous-game rifle, mind you, but charismatically touting its namesake with characteristic Daisy promotional élan.

Only one other Daisy BB gun—if you can believe it—over these 13 decades has bested the Red Ryder Carbine in popularity and sales: the Model 1894, not surprisingly, an even more authentic facsimile of the famous Winchester 94. Just like Marshal Dillon carried when he went after the Apache brothers.

If ever there was a rootin’-tootin’, to-die-for boyhood cowboy dream, it’s the 1894. Maybe the “Yellow Boy” variant, made for a short period for Sears Roebuck, or the highly esteemed “Texas Ranger” edition with a Lone Star adorning the receiver. Which was complemented the greater, should you desire, by an equally veritable pair of “Texas Ranger” six-shooters. Woooo-eee!

The 1894, introduced in 1961 (the same year Charles Lefever died), was the first entry in the immediately beloved “Spittin’ Image” series cloning famous guns. Among them the Colt Peacemaker and the Model 26, which remarkably replicated the Remington 572 Fieldmaster, the iconic .22 pump.

But the 1894 led the way. Easy to see why. So honestly reproduced you’d be arrested today, or worse, for simply carrying one down a city street, it arrived in so many desirable configurations it made your head spin. In addition to the “Texas Ranger” and “Yellow Boy” commemoratives, there was the “Wells Fargo,” the “Golden Spike,” celebrating the transcontinental railroad, the “3030 Buffalo Bill Scout,” the LE “Winchester 94 Centennial,” the “NRA Centennial” and no doubt a few others I’m yet to discover.

The 1894 lasted from 1961-1986 and sold for $12.95 in 1961. Today a nice 1894 in its original box and complement—if you can find it, and depending on edition and condition—will bring up to a half-grand or more at auctions.

But boy, Daisy, forget that . . . just bring it back again.

My imagination flies into ecstatic overdrive thinking about the possibilities—a Native American series: “The Sitting Bull,” with an “eagle feather” dangling from the front barrel ring; “The Geronimo,” with a likeness medallion and brass tacks in the stock; or a limited edition “Little Big Horn,” of only 500, with Custer and Crazy Horse on opposite sides of the stock, boots and saddle, a saber an’ a Cavalry hat on one side of the forearm, a crossed bow, tomahawk and Sioux arrow on the other, and a leather thong from the barrel band.

And while you’re at it, how ’bout an “Adobe Walls” Sharps in .50-90 cal., with Billy Dixon and commemorative art of the fight on the stock? Or a “Wyatt Earp & Doc Holliday” and the gunfight at the O.K. Corral? Or a “Wild Bill & Calamity Jane.”

My, oh my. Makes me wanna grow my ’stache out like Sam Elliott.

Meanwhile, at 74, I’m happy as a kid come Christmas, and how many times can you truly replicate that in a lifetime?

’Course, here I am collecting again at a time I worry about how I’ll tolerably disperse all else I’ve accumulated. But the late Yogi Berra had a thing to say about that as well: “It ain’t over ’til it’s over.”

Seein’ as how Grandpap would have cottoned kindly to such a notion, I think I’ll just keep on keepin’ on.

When it does come quittin’ time, and I make the Pearly Gates, and St. Peter says, “Well, Old Fellow, how was the trip?” I can quietly smile and reply:

“It was a Daisy.”

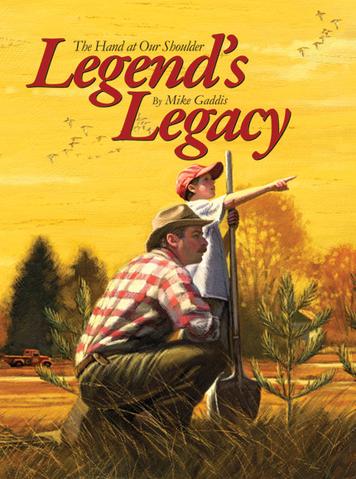

There was a time when the world spun more gently, when family was the axis of its existence and folks lived closer to the land. A time when a gun was no less valuable to the scheme of being than a Bible or a blade, when a hunting dog could be found under the front porch and a fishing pole sat ready in a chimney corner

There was a time when the world spun more gently, when family was the axis of its existence and folks lived closer to the land. A time when a gun was no less valuable to the scheme of being than a Bible or a blade, when a hunting dog could be found under the front porch and a fishing pole sat ready in a chimney corner

There was an age, a space of innocence, freedom and fascination, where every day brought another revelation, and tomorow could never come fast enough. When, as boys and girls, we learned as much from woods and waters as from a spelling book.

Most of all, there were moments of infinite beauty and sharing, when someone laid a hand at our shoulder and led us there. So that later we might lead another, in turn.

Here, in parables of incomparable warmth and intonation, the author of the celebrated books, Jenny Willow and Zip Zap, explores the enchanting realm of outdoor mentorship. Not only in kind and gentle remembrances, but in intuitive vignettes, present and future.

Legend’s Legacy stands unparalleled as an affecting commemoration of the most endearing aspects of our sporting traditions—an inspiring tribute to those who cared, who taught us then and guide us still. Buy Now