One doesn’t have to dig deeply into the career of the “little man with the big Stetson,” Elmer Keith, before realizing that he was a fascinating character in a universe—that of hunting and shooting writers—generously populated by highly unusual individuals. Outdoor writers in general, and gun writers in particular, seem to be inclined to be an overabundance of quirkiness, eccentricity, bombastic personalities, or downright crankiness. Hence the oft-used description “gun crank.” Yet even in the ranks of strange or distinctive personalities, Keith was pretty much in a league of his own. Familiarization with Keith’s career soon leads to an inescapable conclusion that he has to be reckoned, by most any standard of measure, not only a gun writer of enduring appeal, but the king of gun cranks. He was controversial, frequently so cantankerous as to be almost intolerable, and endlessly colorful.

In that context, the title of the revised edition of Keith’s autobiography, Hell, I Was There! is singularly apropos. A man whose propensities really belonged to the days when frontier justice was rough and ready and when every male wore a six-shooter and knew how to use it, he was born two or three generations too late. That never stayed him and, at some point early in life, he seemingly decided to be a living anachronism. He carried a sidearm much of the time and showed a diverse array of abilities so typical of life on the frontier.

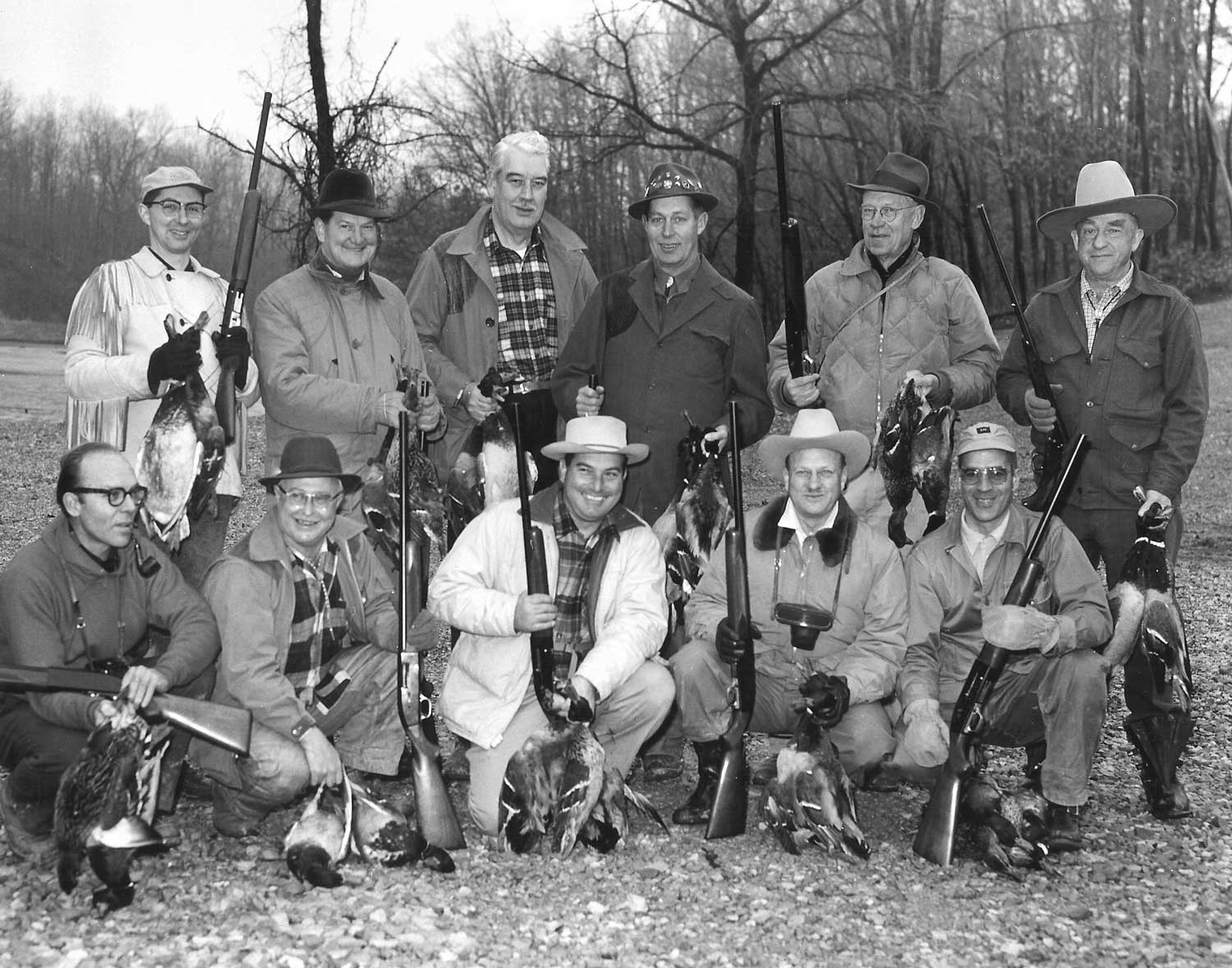

Some of the most famous names in gun writing gathered for a picture at a Winchester seminar, including (standing, from left) Bill Edwards, John Amber, Pete Kuhlhoff, Warren Page, Jack O’Connor and Elmer Keith. Front row, from left are Ray Ovington, Larry Kohler, Tom Siatos, Pete Brown and Jack Seville.

Over the course of a wondrously eventful life, Keith was a guide, outfitter, horseman, cowboy, gunsmith, ammo designer, superb pistol marksman and shooter for all seasons, hunter and writer. It was in the latter capacity he gained fame (or notoriety), and decades after his death he continues to be both revered and reviled. No matter what one’s view of him though, there can be no denying that he was a fascinating fellow.

Elmer Merrifield Keith was born on March 8, 1899, in Hardin, Missouri, the son of Forest Everett and Linnie Neal (Merrifield) Keith. There was adventure aplenty in his veins, thanks to bloodlines of both parents tracing back to Kentucky pioneers who were contemporaries of Daniel Boone. Another forebear was Captain William Clark, the explorer commissioned by Thomas Jefferson to explore lands acquired in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Elmer continued that family tradition, focusing on newspaperman Horace Greely’s advice, “Go West young man, if you would seek your fortune.” Most of his adventure-filled life would be spent in Montana and Idaho.

Certainly, in his case the boy would become father of the man, for from early boyhood onward he loved living close to the land. Keith’s earliest years found him on a farm with sprawling prairie lands for a playground, and it was there he developed an affinity, one as strong as his love for guns and hunting, for horses. He was able to ride almost as soon as he learned to walk, and in time became as knowledgeable (and opinionated) on what constituted a good horse, saddle or tack as he was on firearms.

Not surprisingly, he also had an early introduction to shooting and hunting. In his autobiography, Keith noted: “From my earliest years I seem to have been more interested in guns and ammunition than other things.”

Early in the 20th century, when Elmer was still a small child, his family left Missouri, at least in part because his father found the area was becoming too populous for his tastes. This love of open spaces and few people was something his son came to share. Elmer was never happier than when in a wilderness camp with only a few friends and lots of critters for company. The move took the Keiths to the Montana mining community of Marysville, but they stayed there only a couple of years before reversing track back to Missouri. However, during that initial sojourn, a landmark event in the boy’s life occurred. He became the proud owner of a Hopkins & Allen 22-caliber rifle and almost immediately began making welcome contributions to the family larder through his small game hunting. Elmer developed rapidly into a first-rate marksman, doubtless encouraged by his father’s insistence on receiving detailed reports for every cartridge fired.

Soon, the lad was handling a shotgun as well, although his introduction to scatterguns was decidedly unpleasant. Accustomed to the minimal recoil of his 22, he fired at a fox squirrel without taking “kick” into account. As he later wrote, “What part of the gun hit me, I don’t know. But it cut my upper lip clear through to my teeth and when I woke about three hours later, there was blood all over the side of my face and the oak leaves where I was lying.” Typically, though, this misfortune did nothing to deter his ebullience, just as he never let his small frame interfere with his love of big-bore rifles.

By the time Elmer was on the cusp of his teens, the family again moved to Montana, this time for a much longer period. He was already an accomplished shot and fine woodsman, and with the onset of puberty he became the rambunctious soul, complete with an abrasive tongue, known to posterity. For Keith the veneer of civilized society frequently wore thin, and among the hallmarks of his eventful life were scrapes, contentious and sometimes year’s long arguments and fights. He was a salty, pugnacious character, and his well-known dispute with fellow sporting scribe Jack O’Connor over the relative merits of big-bore versus smaller bore rifles was but one of many examples of a life punctuated by pugnacity. Yet in some senses, Keith’s temper and vocal honesty were among his most redeeming qualities. A man who never minced words or deeds, you always knew precisely where he stood.

Keith’s adolescent years in Montana, a wonderful place for a youngster with his interests, saw his family living a peripatetic existence with frequent moves back and forth between Missoula and Helena. He was terribly burned in a hotel fire during the course of one of these moves. It took a decade for him to fully recover, but the tragic event did little to stay his involvement in bronco busting, trapping, hunting and competitive rifle shooting. He was good enough in all to bring in food or cash on a regular basis.

During the summer of his 16th year, Elmer worked at a bakery and with his earnings bought a hammerless Ithaca double barrel. He soon became a masterful wingshot, a status he had already achieved with rifle and handgun. This period also saw him do a great deal of hunting and become a tough, seasoned young man despite the fact doctors predicted he would never live to reach his majority. Montana was a rough place in those days, and in his words, “a man carried his law with him. If he didn’t, he might not last too long.” That may have been an overstatement, something at which Keith excelled but, accurate or not, throughout his life he made a practice of carrying a six-gun at his side when at home.

The “rough times” Keith described suited the young man just fine and by his early 20s he was a bona fide “gun nut,” with the bulk of his earnings from various jobs going toward what would in time become a veritable arsenal. He was single, footloose and wonderfully free, although a bout with influenza in the early 1920s nearly killed him and did kill a brother. It was at this juncture his family pulled up stakes yet again and moved, this time to Idaho.

Once Elmer fully recovered from the flu, he took several steps that loomed large in shaping his subsequent career. In 1922 he joined the National Rifle Association (NRA) and, anxious to try his hand at match shooting, joined the Montana National Guard as a means of getting into competition. He made the Montana team in 1924 and represented his state in national matches held at Camp Perry. There he met leading gun writers of the time including James V. Howe, Julian S. Hatcher and Townsend Whelen. He became enamored of their way of life and the seed was planted leading to him becoming a writer.

When Keith returned from Camp Perry, he met his future bride, Lorraine Raddall, and he also came back west determined to return to the national competition the following year. It was during this period he made his first appearance in print, albeit in an unpaid capacity. This took the form of a letter to the editor of American Rifleman, Thomas G. Samworth. “Mr. Sam,” as he was widely known, had as irascible a personality as Elmer but was something of a publishing genius. He was the individual responsible for giving the NRA’s stodgy house periodical Arms and the Man a new title, and he was a gun guru in his own right. The contact between the two formed a landmark in Keith’s career. Samworth, seeing Elmer’s shooting ability and knowing his editorial skills could overcome any literary shortcomings, asked Keith to cover the 1925 Camp Perry matches. This, in effect, launched an outdoor writing career that made Elmer Keith one of the most recognizable names among 20th century sporting scribes. From that point forward, moving from success to success, writing lay at the heart of how he earned a livelihood.

Elmer (center) with two hunters on Babcock Creek elk hunt that ended tragically with the death of Bill Strong.

Meanwhile, he had married Lorraine and, over the next few years, the Keiths tried ranching, outfitting, guiding and to no small degree lived off the land. Those years saw him produce an award-winning story on how his hunting partner, Bill Strong, had been killed on an elk hunt, and the $100 the NRA paid was big money at the time, since the country had just plunged into the depths of the Depression.

The reason Keith won the contest, and the primary explanation of his considerable success as a writer, derived from what would always be his strengths—masterful storytelling and in-depth, practical knowledge of his subject matter. A natural raconteur, his stories carry as clear a ring of authenticity as his technical pieces do accuracy. Those considerations being duly recognized, it must also be noted that he was anything but a skilled wordsmith. In truth, Elmer was something of an editor’s nightmare, and there are still old-timers alive who faced the onerous task of dealing with his submissions. Unlike most writers, who become smoother with the passage of time, he became more careless, and his submissions demanded greater editorial attention.

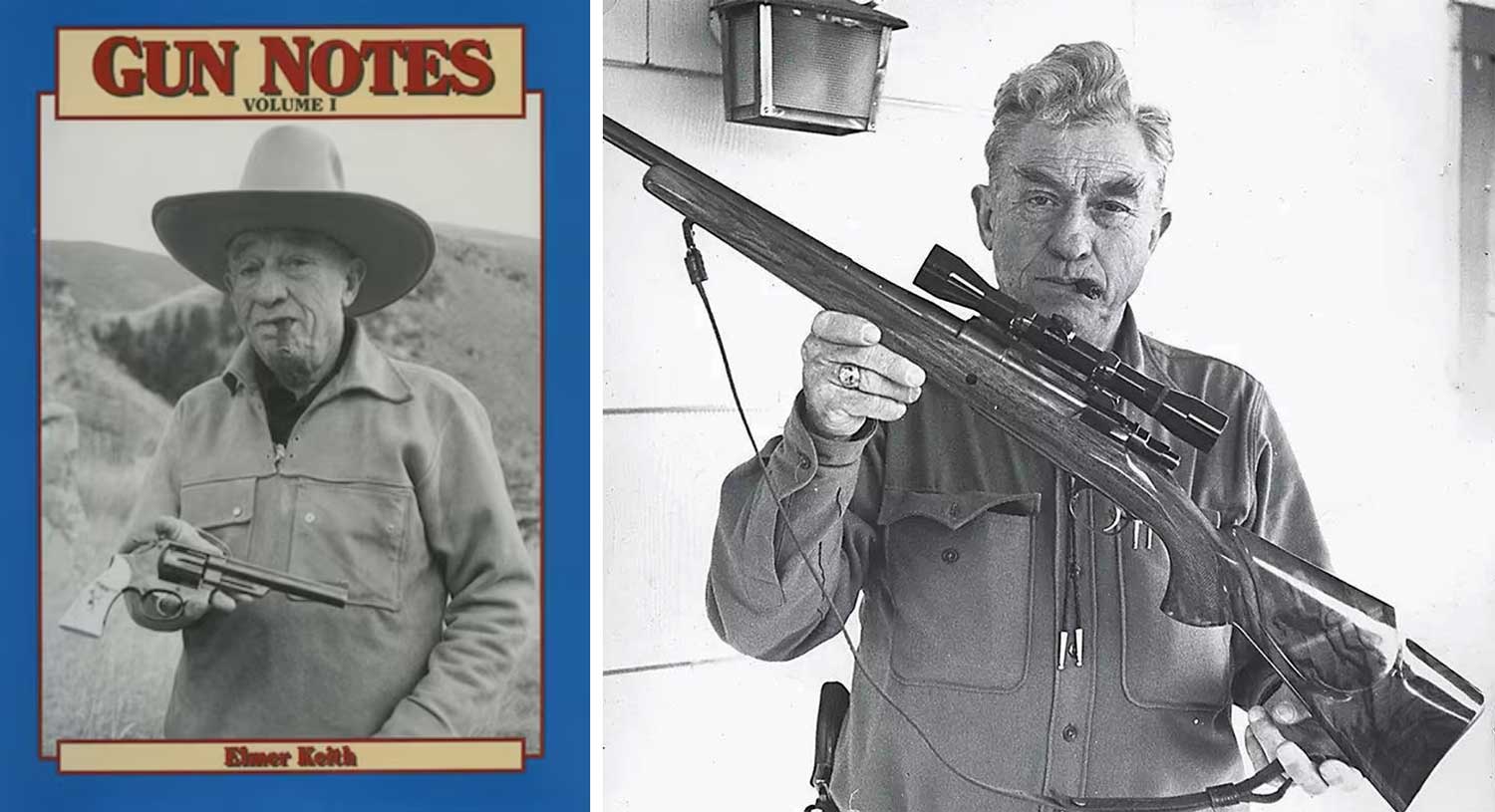

This was especially true once he was something of a living legend. Keith would subject easily intimidated new editors who dared change his words to epithet-laced tirades over the phone, never mind that his submissions were grammatical and stylistic nightmares. Craig Boddington can relate hilarious tales of “Keithisms” and Ludo Wurfbain, who owned Safari Press for many years and published Keith’s 1960s columns from Guns & Ammo magazine as the book Gun Notes, says that Keith’s personal correspondence indicates the man was barely literate. Over the years, various editors took exceedingly rough prose and managed to maintain its wit and wisdom along with vastly improving its literary quality.

Once launched into writing, Keith worked with a will. He sold his first contribution to Outdoor Life in 1926 and soon was making regular contributions to American Rifleman. As his new career blossomed, the Keiths acquired a ranch on the North Fork of Idaho’s Salmon River. They would call the area home for the remainder of their lives. It was also at this juncture, with the Depression strangling, that Elmer made a monumental decision. “I decided to make my living writing and guiding big game hunters and fishing parties.”

That was in 1930 and, interestingly, one of his first guide trips saw him host Zane Grey and several of his angling cronies. For most of the 1930s, guiding would be Keith’s primary source of income as he gradually expanded his writing endeavors. A major breakthrough came in 1936 with the publication of his first book by Thomas Samworth’s Small-Arms Technical Publishing Company. Samworth had left the NRA after a bitter spat, and the crusty old curmudgeon soon managed to be at odds with Keith.

Many years later, Elmer would write: “T. G. Samworth, who operated what he called the Small Arms Technical Publishing Company, commissioned me to write three manuals, which I did. He offered me $250 down and another $250 if they sold. The first one was to be on six-gun cartridges and loads; the second one on big game rifles and cartridges; and the third one on varmint rifles. I wrote the three manuals which were to sell at a dollar apiece. He never did publish the last one. He paid me $250 down on it, and $250 on each of the others. The others sold all right, and plenty good. He later sold the Big Game and Cartridges (sic) to the Stackpole Company and it published a lot more of them. However, I never did get the final payment on either book that he published and, of course, not on the one that he didn’t publish.”

It’s possible all of this is true, but Samworth’s side of the story suggests the first two books had indifferent sales, and it is worth noting that the $250 fronted for each of them was a significant sum in the midst of the Depression. Also, Samworth was a shrewd businessman and my educated guess is that he stuck strictly to the terms of his contractual agreement and that Keith failed to pay much attention to such details. If so, he found good company with countless other outdoor writers past and present. Certainly, Samworth ran a “clean” business. Solid working relationships with 40-odd other writers and dozens of books published under his imprint speak eloquently in that regard. In truth, whether Keith liked it or not, “Mr. Sam” was a mentor who did quite a bit to get him started as a writer. Given the acerbic personalities of both men, one would love to read their correspondence in this literary cat fight.

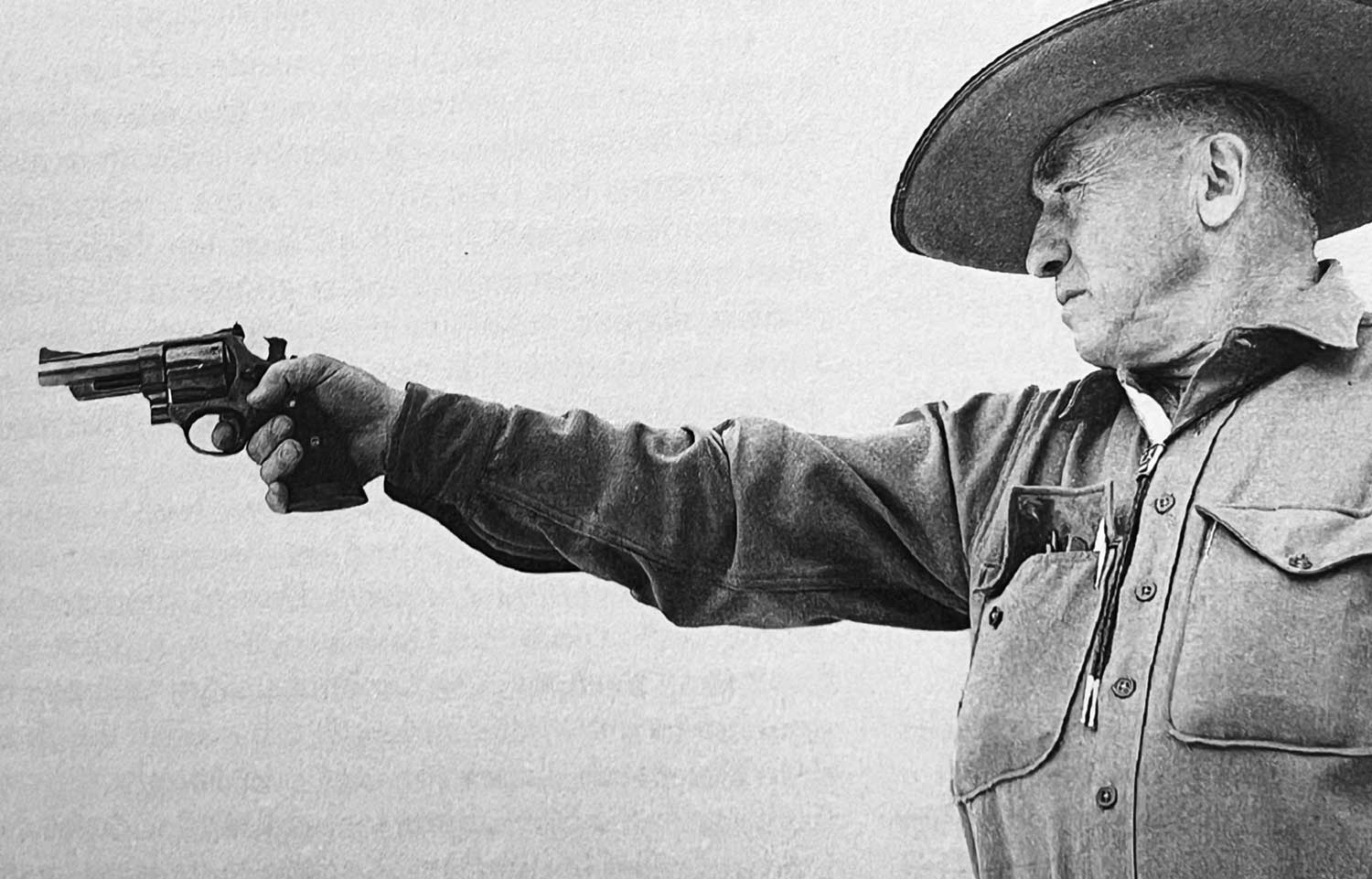

Keith’s bitterness in this particular situation notwithstanding, writing became increasingly important to him. In 1936, he became Gun Edit or for The Outdoorsman magazine, a position he held for a dozen years until a quarrel with a new editor sent him packing. Spats of this sort were a part of his life and, as his writing fortunes prospered, he consciously cultivated the image of an eccentric “character.” Acidity in his dealings with editors was part of that, but so were other factors. He favored oversized 10-gallon hats and often swaggered about with a massive cigar clamped between his teeth. These “effects” were even more pronounced because of his diminutive stature. Yet he always thought big. A psychologist could have a field day with his manifestations of what is sometimes styled “little man syndrome.”

Perhaps the best-known aspect of this feature of Keith was his love of big-bore rifles. He waged a long and bitter battle, at least from his perspective, with Jack O’Connor on what constituted the proper gun for big game. O’Connor, for his part, seemed to tolerate his would-be nemesis from a lofty and sometimes imperious vantage point. He could be vitriolic and even vicious (anyone who doubts this should read O’Connor’s posthumously published The Last Book), but he knew the meaning of restraint. That word wasn’t in Elmer’s vocabulary. He reveled in controversy, and his outspoken, down-to-earth approach to matters endeared him to legions of readers just as O’Connor’s exquisite gentility and mastery of wordsmithing brought him a similar large following.

Elmer Keith knew tragedies and setbacks aplenty—the fire that would have killed a lesser man, rejection when he wanted to serve his country on active duty in World War II, losing one daughter at birth and another as the result of a car accident and periodically fighting emphysema throughout his life. Somehow, he persevered. There were business setbacks as well, such as the aforementioned brouhaha with Samworth and a messy situation with his 1946 book, Keith’s Rifles for Big Game (the publishing house closed shop and half the first printing, after transfer to another publisher, was destroyed in a warehouse fire).

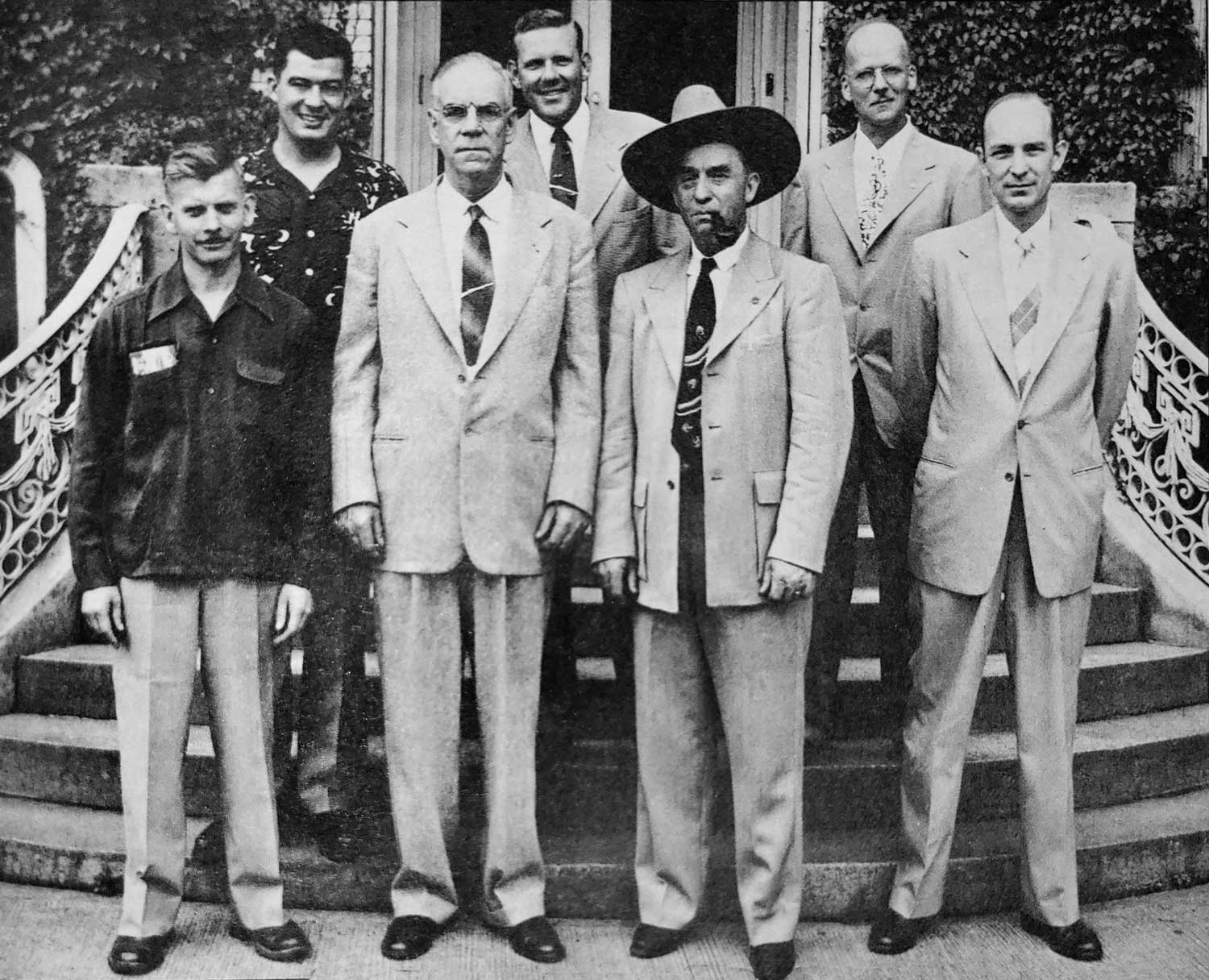

The technical staff of the American Rifleman gathers for a photo in Washington DC. From left, back row, are Bob Wallack, Rudy Etchen, and Harold McFarland. Front row are Phil Sharpe, General Julian S. Hatcher, Elmer Keith and Bud Waite.

Set against this was becoming part of the Technical Staff of American Rifleman in the 1940s, then in the 1950s he wrote books that sold well and didn’t run into problems with the publisher. Those were Shotguns by Keith and Sixguns by Keith, both with Stackpole Press. These variegated activities collectively sufficed, by the end of the 1950s, to make him one of America’s most venerated gun writers. Over the final quarter century of his life, his would be a household name in the shooting world. Those were good years, ones spiced by plenty of travel, exotic hunts and sheer enjoyment of his hard-won place as a gun authority.

Keith’s later career saw him serve as executive editor of Guns and Ammo, although he was constitutionally incapable of doing any hard editing. He also worked with and wrote for a sister publication, Petersen’s Hunting. An offshoot of the latter, Petersen Publishing Company, published several of his books including Guns and Ammo for Hunting Big Game, Safari, Keith: An Autobiography and Hell, I Was There! (the final work was an expansion and rewriting of his autobiography). In many ways these were his best books, thanks in part to careful editorial input but also because he now spoke with the accumulated wisdom of a grand old man of the gun world. The gun crank had become a king.

Starting with a serious heart attack in 1957, Keith’s health began to plague him. He would live another 16 years, although the drive and stamina that had long typified him waned. Still, just shy of his 80th birthday, he wrote: “I have no intention of retiring. You retire, you become a vegetable and usually last six months to three years. I don’t care for that kind of an end. I’d rather keep working and die with my boots on if necessary.”

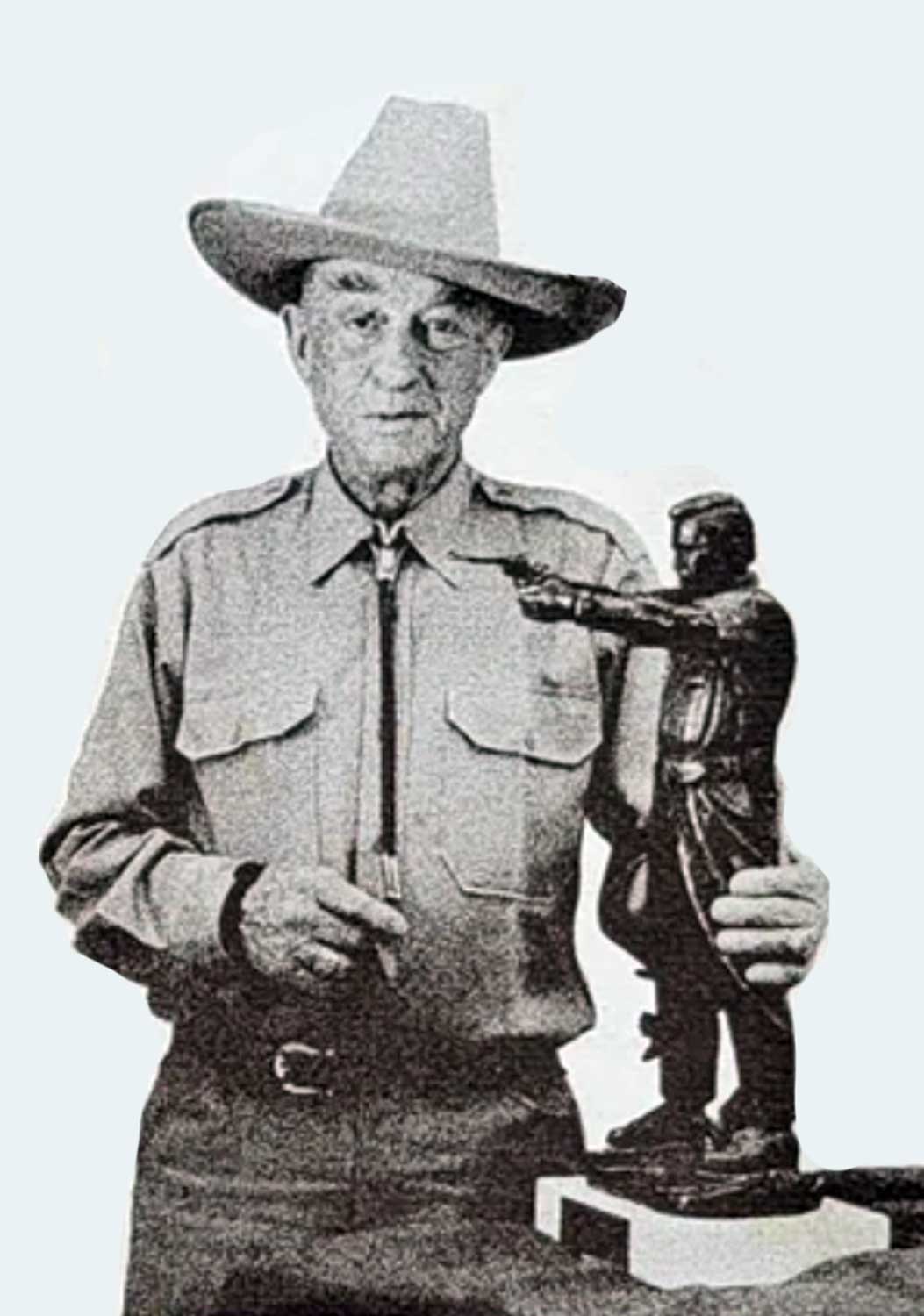

Fittingly, in 1973 Keith was the recipient of the inaugural Outstanding American Handgunner award, and from that point forward he relished holding center stage and pontificating on any and all gun matters. He died on Valentine’s Day a decade later, amusing and abrasive, opinionated and vociferous, right to the end. Turmoil dogged his days, although he undoubtedly courted and likely reveled in it, but there can be no denying his place in the literature and lore of guns and gunning. Sporting posterity is richer for his endeavors and the vim, vigor and even the vituperation he brought to us all. He left an indelible mark, one tinged by controversy. I rather suspect he would have delighted in the enduring controversy.

Fittingly, in 1973 Keith was the recipient of the inaugural Outstanding American Handgunner award, and from that point forward he relished holding center stage and pontificating on any and all gun matters. He died on Valentine’s Day a decade later, amusing and abrasive, opinionated and vociferous, right to the end. Turmoil dogged his days, although he undoubtedly courted and likely reveled in it, but there can be no denying his place in the literature and lore of guns and gunning. Sporting posterity is richer for his endeavors and the vim, vigor and even the vituperation he brought to us all. He left an indelible mark, one tinged by controversy. I rather suspect he would have delighted in the enduring controversy.

Jim Casada is Editor at Large for Sporting Classics and a lifelong student of the history of hunting and fishing. To learn more about his work or to receive his free monthly e-newsletter, visit jimcasadaoutdoors.com.