No art form can touch all people with the same force, but it would be hard to imagine a medium with more universal appeal than the bronze statue.

It can be sculpted into a delicate hummingbird resting on a tabletop, heaped and hewn into a life-size grizzly guarding a museum entrance. Bronze can illustrate painstaking realism or be gracefully impressionistic. Bronze is timely; art buyers are turning to it in droves as their walls fill up with paintings. Bronze is timeless; the medium is so fundamentally unchanged that an artist from 3,000 years ago could walk into most modern foundries and know what is happening in each step. More analysis is possible — you can ponder the attraction of a piece that changes as you touch, turn or light it differently I’d advise against further dissection though. Simply enjoy the work of the artisans that follow … that will be more than enough to illustrate the universal appeal of bronze.

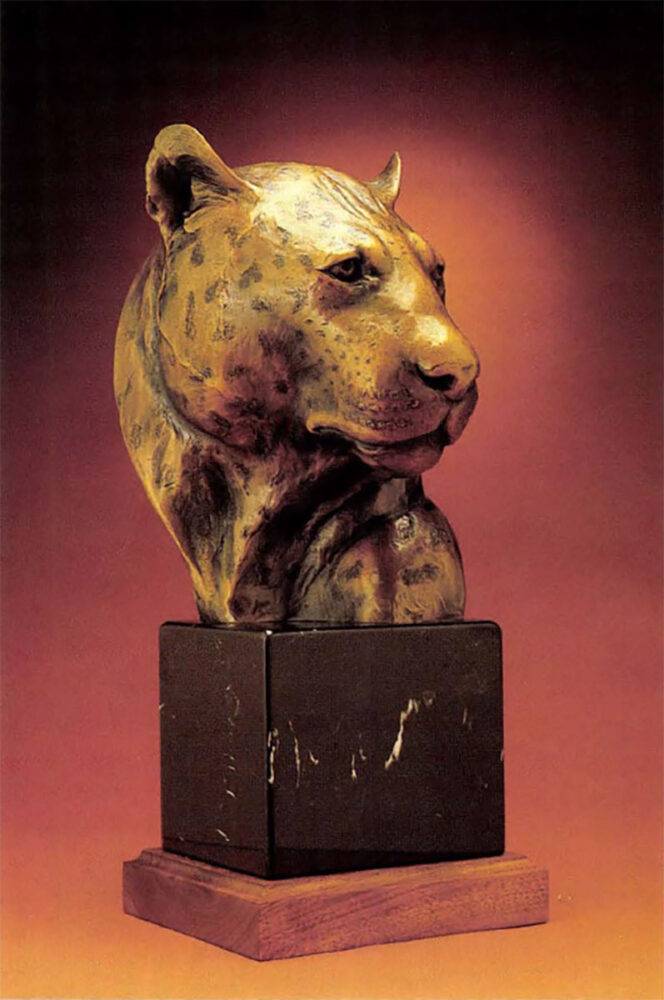

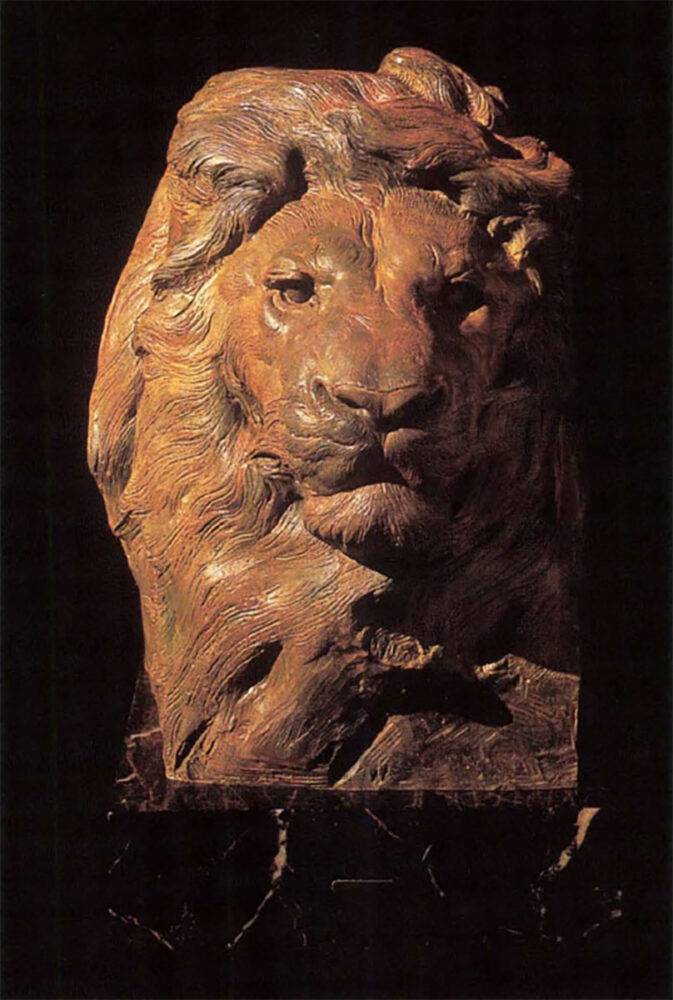

Forest Hart

Forest Hart created this stunning bronze of an African leopard.

Forest Hart has perhaps one of the best backgrounds an animal sculptor could hope for: that of a museum taxidermist. Preparing mounts for countless displays, Hart became intimately acquainted with the anatomy, form and musculature of hundreds of animals. He became so adept at life like taxidermy that he developed an extremely accurate measuring system for constructing animal forms, and eventually created a business that sold those forms to other taxidermists. One would assume then, that when Forest Hart turned to bronze sculpture to depict animals, that every hair, muscle and fiber would show up in his work. But that’s not the case. “I work loose enough that what I produce is definitely artwork and not miniature taxidermy,” Hart says. “I try to strike a happy medium; I want to work fairly loose, but at the same time, detail is extremely important in some areas, like hooves and ears. I strive for an accurate profile of each animal.”

Hart makes his home in Hampden, Maine, but travels extensively “I spend a couple of months each year in Newfoundland, observing wildlife and guiding hunters for caribou,” he notes. Hart does some of his best research in the field, watching animals with binoculars or spotting scope, often modeling clay as he observes. “I’ve tried photography, but it seems I spend all my time fiddling with cameras and not enough watching wildlife. Often, I just watch an animal, and when I see a great image I just close my eyes and remember it. That image is often what I’ll represent in a place.”

Back at his studio, Forest limits himself to about three hours of effort each day. He’s found that if he pushes harder than that, he burns out. “I hate to quit after three hours, but I’ve found that it forces me to take my time and stay excited about the work. When I’m out of the studio, then, I think about the piece constantly, especially when I’m out for my daily run. I get up at 4:00 or 4:30 every morning, go for my run, and when I get to the studio I’m ready to rip and tear and go to work.”

Fred Boyer

Most sportsmen would kill for a childhood like Fred Boyer’s. A native Montanan, Fred was tagging along on his father’s fishing trips when he was three years old. Later, he learned to hunt in the mountains, work with pack animals, guide hunters, fight fires as a smoke jumper.

Artistic talent was also a part of Fred’s childhood, apart in which he excelled. He studied art at Montana State, taught it to schoolchildren in Alaska and again in Montana. Then, in his own words, “One day I saw some sculpture and thought ‘I can do that!’ ” He did it well enough to leave his teaching career and devote his life to producing fine bronze sculpture.

Fred Boyer’s realistic portrayal of caribou, Mulchatna Ballet.

“I’ve spent so much time hunting elk, sheep and goats that they seem to be my favorites. They are all so intelligent and require you to find them in such remote, inaccessible areas. Being out among them so often has a lot to do with being inspired to sculpt them. I guess if I lived in New York, I’d do people.”

Boyer’s works are known for their accuracy and attention to detail. “I appreciate simplified pieces, but I work fairly tight and try to capture muscle and detail. I do what is called additive sculpture, where I actually do an image of the animal as if it were skinned out. Then I begin to add clay for fur, etc. For that reason, I feel it is important to study wild specimens; penned-up ones get too soft. The wild ones are the best of the species, lean and muscular. Bronze lends itself well to animals for that reason. I really feel you can capture their spirit.”

James Stafford

Jim Stafford’s love for, and knowledge

of, high-country wildlife is obvious in

this bronze of a mountain goat.

Jim Stafford has a simple, but exhaustive, goal as an artist: he wants to portray all of the world’s wild sheep in bronze. There may be no sculptor more suited to that task than Stafford who, as you might have guessed, is an avid sheep hunter and observer. ”Ask any sheep hunter and he’ll tell you — it gets in your blood. As a hunter, I enjoy the remote country they inhabit. As a sculptor, they are an excellent study. They have a full form that is unique. I spend all the time I can in sheep country, hunting, photographing and sketching them.” A Washington native, Stafford’s childhood found him drawing and sketching animals as avidly as he hunted them. He worked as a taxidermist for awhile, then studied to become a commercial illustrator. He was exposed to, and worked in, “virtually every medium” enroute to receiving a BA and M.FA. in art. But attendance at a summer study of wildlife painting in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, would expose him to the genre where he would leave his greatest mark. Once Stafford settled into sculpture, he got involved in a big way; he experimented with, and perfected some new patinas, designed and built two foundry systems, and continues to do his own casting, welding, chasing and patina work. Stafford labels himself “an impressionistic realist. I like to think that I can model like Rungius could paint. I try to work sculpture fairly fast, hoping that I can stop the piece before I kill it. I’m a mass and movement person; I feel that if you don’t have the right proportions, all the detail in the world can’t help you.”

Philip Marcacci

When Philip Marcacci suffered a disabling neck injury in 1979, he had no idea the accident would turn him into a topnotch bronze artist. The injury required the removal of three cervical disks from his neck, resulting in a severe loss of dexterity in his hands and forcing him to live with chronic pain. But Marcacci, an irrepressible optimist, refused to let the incidents our him. “If you need to look for the good in everything, the accident was a positive,” Marcacci stresses. “I couldn’t physically handle the welding torch I used for my steel and brass sculptures anymore, so I went looking for clay.” That search led him into the studio of John Soderberg, who Marcacci feels is one of the nation’s best sculptors. “Soderberg and I hit it off immediately,” Marcacci recalls.” He was the most unusual teacher I’ve ever had. He’d walk in while I was sculpting, look at the piece, say ‘No’, pick up a knife and lop off some clay and say ‘do it again: He’s changed the way I look at art.”Marcacci also worked with Soderberg to develop Classic Clay, which the amiable Californian sells to others and, of course, uses in his work. Marcacci sculpts a variety of animals and birds, but raptors are his favorites. ”I’ve always had a fascination with birds of prey, especially owls;’ Philip says. Marcacci is a devout family man; he’s a househusband and Cub Scout leader for his sons by day, a sculptor late at night. “I usually can only handle two or three hours of sculpting a day, four days a week. If I push any harder, I end up taking a week off to recover.”

His limited work time hasn’t overwhelmed his perfectionist nature, however. “I did a falcon piece awhile back that I had three falconer friends critique. I told them ‘tell me what’s wrong with it: They each came back with about a page of notes, which I combined, then went back to work. When they looked it over again they were satisfied, so I figured it was okay.”

Frank DiVita

Blue Waters Sailfish by Frank DiVita.

Frank DiVita lives in Kalispell, Montana, but his exposure to fine art goes back to his childhood in Genoa, Italy “I was exposed to the work of the masters at an early age and wanted to be an artist,” DeVita remembers. “But my parents discouraged me. Not because they didn’t like art, but art was not very popular then. They didn’t want to see me wanting or lacking anything. But as my friends have told me, it’s fortunate you can’t crush the spirit of an artist.” Fortunate, indeed. DiVita is now among the world’s best bronze sculptors, and his work is on display in galleries as distant as China and Sweden. It took a while for the modest craftsman to find his niche, however. He intended to become a medical illustrator, realized he didn’t want to leave Montana for the cities that held such jobs, and settled into teaching. During his teaching career he developed his sculpting ability, and after one of his bronzes won Best of Show at the CM. Russell Western Art Show in 1978, Frank decided it was time to become a full-time artist. Since then he has devoted most of his bronze work to portraying birds. “I love all birds,” DiVita says, “but especially birds of power and birds of delicacy. My two favorites are the eagle and the hummingbird.” DiVita’s works are detailed and accurate; he works tight and offers no apologies. “It’s much more difficult to work tight and still bring out the essence of the animal — there is always the chance that the detail will take over. But the exterior becomes the skeleton that encompasses the essence of the creature. The lines and details could be melted off, and the sculpture would still essentially be the same.”

DiVita maintains a relentless work schedule: he employs six craftsmen, many of them former students, who assist him with foundry work and the intense labor that bronze requires. Whether they are working on a small piece for someone’s home or a large monument, Frank DiVita is driven by a search for perfection. “We treat every piece the same. If something goes wrong, we simply start over. If I’m driving from Montana and my goal is Chicago, I’m not content to wind up in South Dakota. I want to get there.”

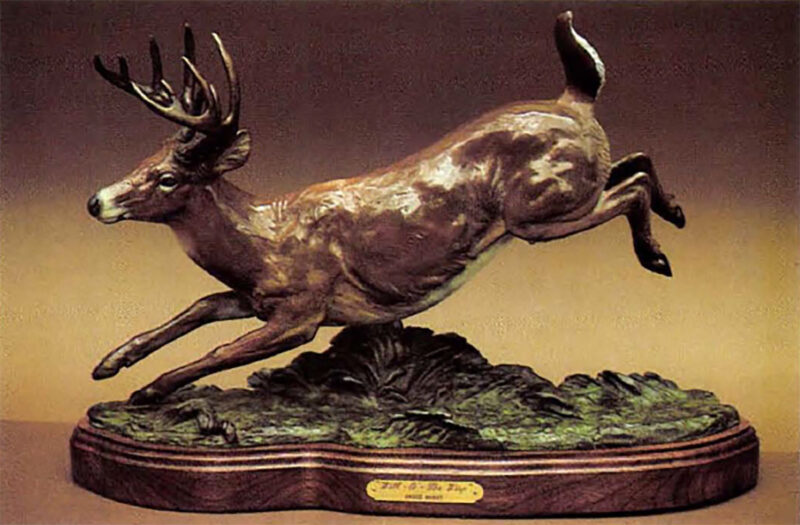

Bruce Brady

Bruce Brady’s bronze work reflects over 50 years of outdoor experience, but his tenure as a sculptor is really in its infancy After all, his success as an artist is the third career he has tackled, and excelled at, since his graduation from the University of Mississippi. Brady’s post-graduate footsteps seemed to be following in his father’s; the elder Brady was a country lawyer, and Bruce jumped into law school, passed the bar, and established a successful practice that spanned 10 years. But his journalism degree and part-time freelancing work for sporting magazines tugged at him until he left law to pursue a career as an outdoor writer. Brady was successful at the typewriter as well — he only abandoned his post with Outdoor Life when another calling struck him.

“Our family was donating hand-made items for a church auction, and everybody had something to contribute but me;’ Brady recalls. “My son Bruce tossed me a ball of clay and told me to model a sheep head like one I had mounted in my office. I carved the clay with a letter opener, my wife Peg fired it in our oven, and it brought$475 at the auction. I about fell over!” Like someone under a spell, Brady gobbled up everything he could read and observe about bronze sculpture. “When I was learning to be a writer, I’d sit down with a great story and a red pencil and dissect it to see why it was so wonderful. That’s the same approach I took with my art.”

Bruce Brady’s Will O’ The Wisp whitetail deer.

Technical execution was Brady’s only concern — he had no lack of inspiration or “sculptor’s block” to battle. “I guess I’m not an uneducated artist because of the vast experience I’ve had in20 years of photojournalism, and my hunting and fishing has also been invaluable. I feel like I’ve got an advantage over someone sculpting a whitetail deer who didn’t just shoot, skin, butcher and eat one like I did a while back.”

Brady is a full-time sculptor now, devoting his considerable energy to what may be his final career. He is, however, leaving his options open. “I’d love to paint, too;’ he sighs. “But I’m so devoted to this medium right now -I guess that will have to wait another 10 or 15 years.”

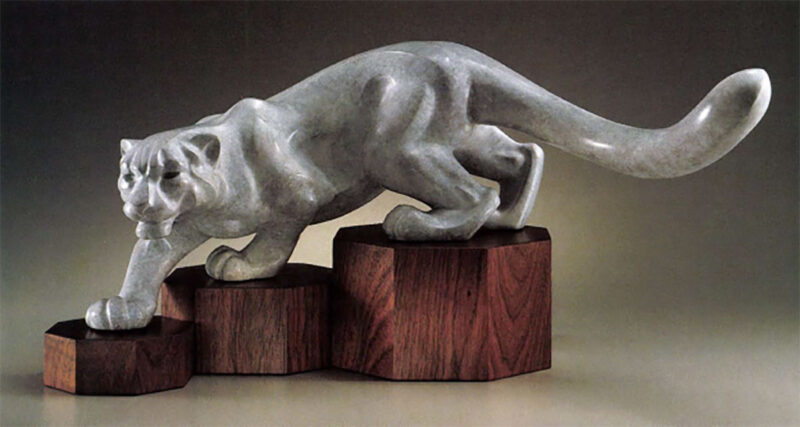

Rosetta

Rosetta’s fascination with the world’s big cats runs deep; she can recall vivid childhood dreams of them even today. “I can remember having nightmares of cats stalking me, circling the house, trying to get in the windows as a little girl. “But in one dream, things were different. Instead of being afraid, I decided to go out and face the cat. I made friends with him and wasn’t afraid of them anymore.”

She didn’t know it then, of course, but shedding that fear may have been an important step. Rosetta now devotes most of her sculpting energy to portraying the feline form in bronze. “I was one of those lucky kids who knew they were going to be an artist very young. I can remember my father giving me lessons in perspective at an early age, and I used to take soap from the bathroom and carve it into little animals.”

Rosetta captures the grace and fluidity of cats in her impressionistic piece, Snow Leopard

Despite her early attempts at three-dimensional art, it took Rosetta a while before she would find her niche in sculpture. After receiving a BA in art from the University of Delaware, she worked in a design studio, an ad agency, and eventually started a business as a freelance lettering designer. “I was going merrily along doing that, when a painter friend asked me to sculpt a bust of him while he painted a portrait of me. That experience hooked me, even though I didn’t know some very basic things about bronze — like you forged it in a foundry.”

After winning several awards and doing some commissioned work, Rosetta gave up her freelancing business to focus on sculpture fulltime. Naturally, cats have been her favorite subject. “They are the most incredible moving animals I’ve ever seen, fluid and beautiful. That’s why I’m not trying to depict every little bump and curve — I emphasize grace and fluidity.”

John L. Jones

JL. Jones’ Wading The Run.

Building swimming pools may not seem like the perfect groundwork for a sculpting career, but don’t tell that to John L. Jones. He’d worked in the construction business for seven years before becoming a full-time sculptor, and was struck by the parallels. “It took me a while to see it, but I realized that sculpture was a lot like construction; building something with your hands out of rock. I like being able to touch it, to walk around it when I’m finished.”

Though he’d enjoyed art since childhood, Jones was settled into the construction business, or so he thought, when his boss asked him to do some artwork of his boat. Something clicked inside as Jones worked on those projects, and he decided to go back to school for some more formal training. A sculpture class later, and John L. Jones had found his medium.

Fans of his work appreciate his honest portrayals of hunters and fishermen afield. “It doesn’t seem that many artists do people, and I like to take a different perspective,” Jones says. While his images of duck hunters and trout fishermen remind sportsmen of their own experience, he is not one for minute detail or exacting realism. “I try not to make faces, for example, too perfect. You hardly ever see anyone out there like that. All my favorite painters are impressionistic, and I’d like to become even more so as I grow…to have less distraction, to say more with less.”

Today, the world of construction seems long behind the bright young artist. He works in a small studio next to his home, gaining inspiration from outdoor adventures and monthly trips to galleries like Collector’s Covey in Dallas. “If I didn’t like to stay up late and work, or wake up in the middle of the night with an idea, I wouldn’t do this. My friends tell me that I’m obsessed with sculpture,” Jones laughs. “I guess they’re right.”

Bob Guelich

Serengeti Breeze reflects Bob Guelich’s move toward impressionism.

Bob Guelich has been sculpting bronze long enough to remember when hunt able wildlife was all that buyers showed interest in. “We used to say that if you couldn’t sell it,” Guelph muses. “Fortunately, that attitude has changed.” The personable Texan started his career using the quail, ducks and doves he’d bagged as models, but he’s portrayed many other bird species since then. “I’m currently working on belted kingfishers, and I also enjoy doing eagles and owls.”

Known for colored bronzes that are vividly realistic, Guelph would like to be more impressionistic. “I work very tight. I really don’t want to, and I’m trying to loosen up. I think if your sculpture becomes too tight, you risk losing that feeling of motion.”

A lifelong artist, Guelich has also worked as a painter and engraver, and for a short time, left the world of art to become a businessman. “I tried not to be an artist then,” work and everything. I lasted three months. It was terrible!”

Returning to bronze, and wildlife, came only after exposure to many mediums. “I compare it to going to medical school. You are exposed to everything in your field, and you eventually decide what you like best. The more you see, the more you narrow your choices.” It appears tax Bob Guelich has found the right area.

Lorenzo Ghiglieri

When international figures like Pope John Paul II and Mikhail Gorbachev visit the US, they create quit a stir among Americans. Oregonians, though, might have been even more elated when the Pope and Gorby left after their last tours. Why? Because the booze sculptures of Portland artist Lorenzo Ghihglieri accompanied them on their return trips. You don’t have to be a celebrity to own a Ghiglieri, of course, but he does have some impressive collectors. Among the mare King Juan Carlos of Spain, Ronald Reagan and Michael Jackson.

Ghiglieri is an accomplished painter as well, but his bronze work often draws comparisons to those of Remington and Russell.

High & Mighty – Bighorn Sheep, a striking, .999 silver sculpture by Lorenzo Chiglieri. The piece is also available in a bronze limited edition.

The talented sculptor was born and reared in southern California where he played barefoot in the hills and swam in the surf of nearby beaches. He lived in a world of ethnic blends that enriched his understanding of world culture. His father and grandfather were sculptors, and his mother a French artist. As a young boy he received formal art training, and he studied the works of Rembrandt, Corot and other masters at local museums. At 17 Ghiglieri won a prestigious art scholarship. By 20, he was working on national commissions. At age 22, while serving in the U.S. Navy he was commissioned to paint what became a gift from the United States to Great Britain for Queen Elizabeth’s coronation.

In the next few years Ghiglieri won over 20 national awards in graphic design and magazine illustration. Helearned the discipline of communication that laid the foundation for principles which give meaning and value to his art.

Though Ghiglieri has depicted numerous themes in his work, some of his most stirring sculpture is of wildlife. These pieces reflect a lifetime of personal outdoor experience. He has taken countless wilderness treks in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. Traveling through such rugged country has allowed him intimate glimpses into the lives of the wolf and caribou, eagle and grizzly. Recent Ghiglieri bronzes depict African wildlife as well.

Reflecting on his art, Ghiglieri has said, “Most of my sculptures and paintings are done to remind us of the important things in life; the bountiful beauty of nature, the value of caring and being responsible, the value of recognizing the true source of our gifts and giving thanks, the value of honesty and dignity, and above all, the value of faith.”

Larry Isard

Like many of the country’s top bronze artists, Larry lsard’s inspiration comes from an intense love of wildlife and a rich sporting background. He differs from his sculpting contemporaries in one major regard, however. For Larry Isard, creating fine bronze statuary is just a hobby. An assistant director of the Cleveland, Ohio, Museum of Natural History, Isard has many more ideas than moments to bring them to life in sculpture.

I’ll come in on some Saturdays and sculpt, or work when the museum has an evening program, but my sculpting time is pretty limited,” Isard admits. Don’t count the museum as a complete handicap, though. When Isard begins work on his latest bronze he delves into “a tremendous picture file “of animals and birds that the museum keeps for reference.

On Hold – English Setter by Larry Isard.

Indeed, Isard’s early employment with the museum as a taxidermist and exhibits preparator were the very foundation of his art. “When you get involved in making a mount of a large animal, you first make a small model of what will eventually be the finished form,” Isard notes. ”As a taxidermist, I skinned and prepared literally thousands of animals for exhibits, and you soon get a real understanding of what’s going on underneath their skin.”

Despite his intimate knowledge of anatomy, don’t expect to see excruciating detail in an Isard bronze. “I have no interest in carving every feather,” he stresses. “There is much more to a living animal than flesh and bones. I want to capture that ‘much more’ — that tension and energy that wild animals possess.”

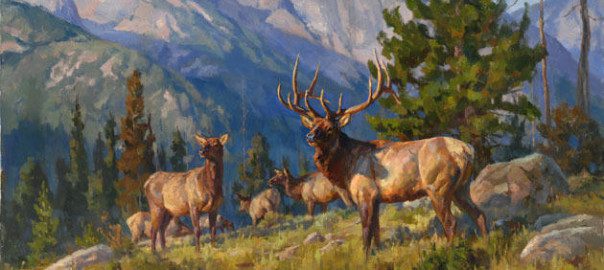

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now