My music career was very short-lived. It began in fifth grade when Mr. Browne recommended I mouth the words to the National Anthem. According to him, I “sounded like a crow.”

As with many young fellas, I shifted gears and started playing the trumpet. I was pretty good until eighth grade, but that ended as fast as it got started. The way I figure it is that after a vigorous start on my part, my classmates simply caught up. Nowadays I sing a bit in the car until the laughs start in the backseat. I rarely sing in the shower.

Maybe I’m tone-deaf, but my wife is a different story. When Angela sings anywhere—while driving, in church, or while gardening—I am in awe. She has the voice of an angel, so much so that she’s constantly being recruited to join the choir. Her singing voice might be tied in to genetics. Her Aunt Maryann has a great voice, plays just about every instrument known to mankind, and even teaches the subject. Me? I stand on the sidelines, keep my mouth shut, and listen. It’s better that way.

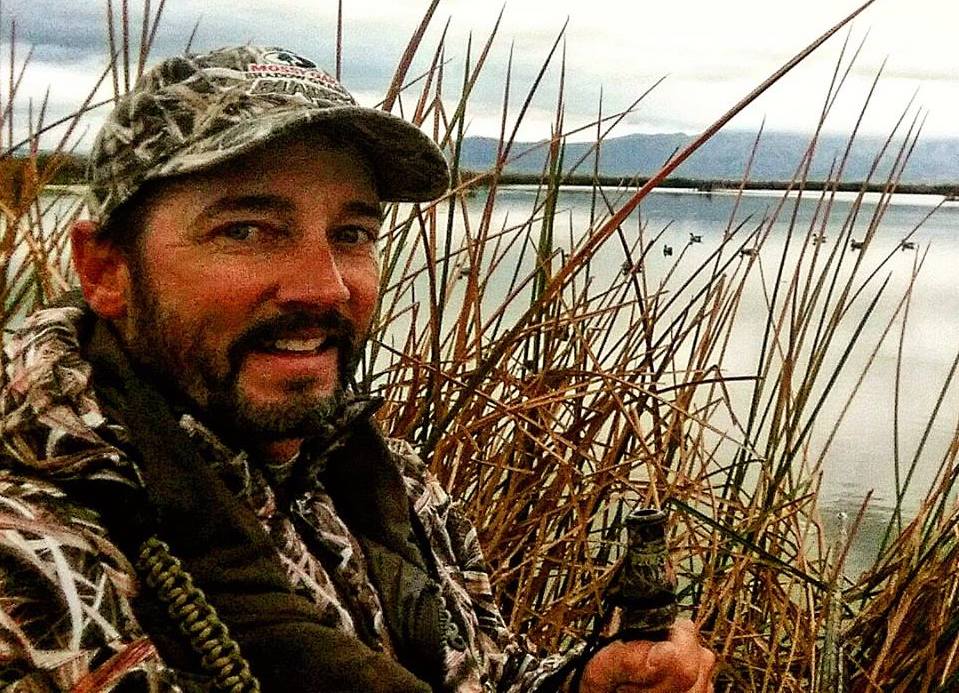

When it’s waterfowl season, you’ll find Bret Wonnacott in a blind. Outside of that, it’s anyone’s guess where he’ll be, but a safe bet is bird hunting, training dogs, or fishing.

But the problem is that they make it look so easy that I feel I can compete. It’s been that way with other things, too. Take Michael Jordon drifting above a point guard, forward, and center’s head from the top of the key to the rim. His jam is so effortless that I think I can do it, too. There was never a question of keeping the motor running in my linebacker legs. In their day they chewed up a lot of running and quarterbacks, but since they’re similar in size to a California redwood, they don’t get above the rim. It doesn’t matter how easy MJ makes it look.

A while back I saw a video posted by my friend Diane Deming Gates. It was of her Hall of Fame husband, John Rex Gates, and a fella named Bret Wonnacott. They looked to be in the midst of a midday parking lot party. Brett is from Utah, and he was in Grand Junction to visit with the Gates and swing by the Field Trial Hall of Fame and National Bird Dog Museum.

My understanding of Bret was that he was an upland bird dogger, so it made sense for him to be with the Gates and in Grand Junction. He and JR were probably shooting the bull about dogs past and present, talking training, you know the drill. But all of a sudden he whips out a duck call and starts laying out a few licks. Some hail calls, some comeback calls, the chuckles associated with contented feeding, and even a few quacks.

His calling was so good that I looked at the top of the screen. I figured Bret was gonna put some greenheads on the asphalt somewhere between the yield and the handicap-parking signs. I saw no birds flying, so I looked at the bottom of the screen to see if they already landed. The guy is that dang good.

John Rex Gates and Bret Wonnacott share a laugh at the National Bird Dog Museum.

I was inspired so much that I descended the stairs to the basement. I found my waterfowl bag, pulled out an old Olt 66, and hit some licks. It was June, a long time since waterfowl season closed, and I was a tad rusty. No matter; it all flooded back. In no time I was Brett Wonnacott, and I sang the sweetest of songs to waterfowl everywhere. Behind my home is a marsh, so I grabbed a few black duck dekes and headed out. There were always a few ducks back there.

Calling ducks in near-summer is an odd business, but I tossed those cork blocks into the water and crouched low in the cord grass. I didn’t have to wait long before a half-dozen birds were flying overhead. I waited until they passed and hit ’em with a quick hail call followed by a comeback call. They kept flying. A short while later I saw some more, and I hit ’em again. No dice. The tide must have turned, for there were black ducks flying everywhere. I had no takers, so after an hour or two I picked up my dekes, coiled the anchor lines, and headed home. They went back in the basement where they belong.

Duck calling sounds like a symphony, or at least it should. That’s probably why Bret has won five state calling titles in Utah and has competed in five World Championship Duck Calling Contests in Stuttgart, Arkansas. Pros like him make things look so easy that the rest of us are inspired. And who knows? I may be tone-deaf after all.