“Dennis identifies with big, powerful animals; the bold and the dangerous,” Smith says. “But he shows you some nuance of them that you’ve never seen. It’s like he knows we have some preconceived notion of what a certain animal is, so he doesn’t bother with that.”

Bear in Ice

The hike down to the remote section of Washington’s Cascade River had been a rugged one for Dennis Anderson. The hillside was steep and the footing treacherous, but the roar of the water ahead hinted at just what his father had promised: a view of the wild river that few ever saw. But the young man was about to get far more than a glimpse of the gorgeous Cascade.

“When I broke through the willows and alders near the bank, I looked to my left and there was a black bear cub standing there, looking at me,” Dennis recalls. “Then to my right I saw another one. I heard a ‘woof!’ and I turned to see the sow directly in front of me. I looked at the river, which was moving right along, and wondered just how far downstream I was going to wind up when I jumped into the thing to avoid getting killed!”

Fortunately, the sow gathered her charges and beat a hasty retreat before Dennis had to risk a whitewater getaway. But the tense encounter burned itself so firmly in Anderson’s mind that, while describing it to me in his studio last October, he was able to recall the experience in vivid detail. Not the species of plants or the types of rocks, but the intense emotions . . . worried sow, anxious cubs, tense interloper. Minute details? Sketchy or absent. Raw fear and anxiety? There in spades!

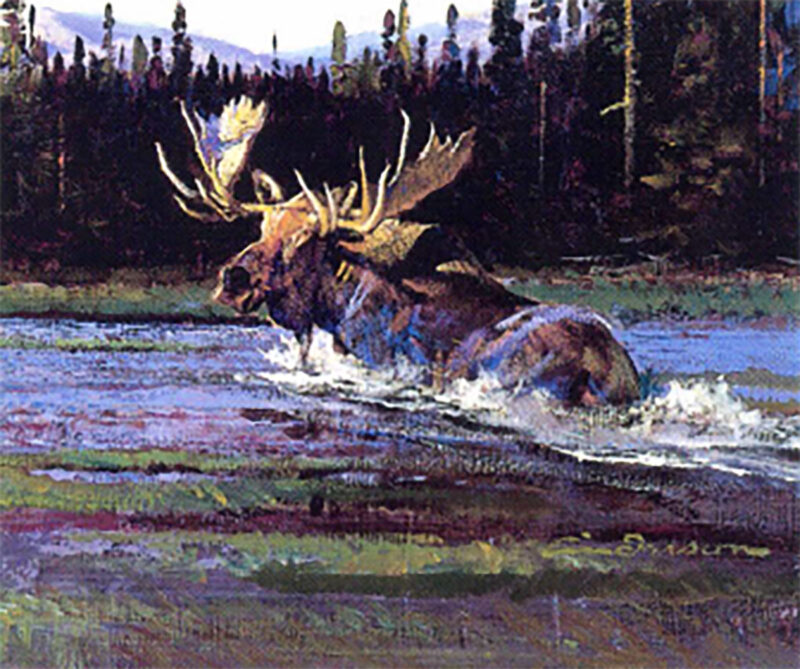

This story, of course, is a metaphor for Dennis Anderson’s art, both his bronzes and his paintings. Dennis occupies a unique niche in the world of wildlife art: as one of the foremost animal sculptors, yet also as a highly acclaimed painter whose acrylics exhibit the same intensity and feeling found in his bronzes.

A pack of hounds splash after a jaguar in Border Patrol.

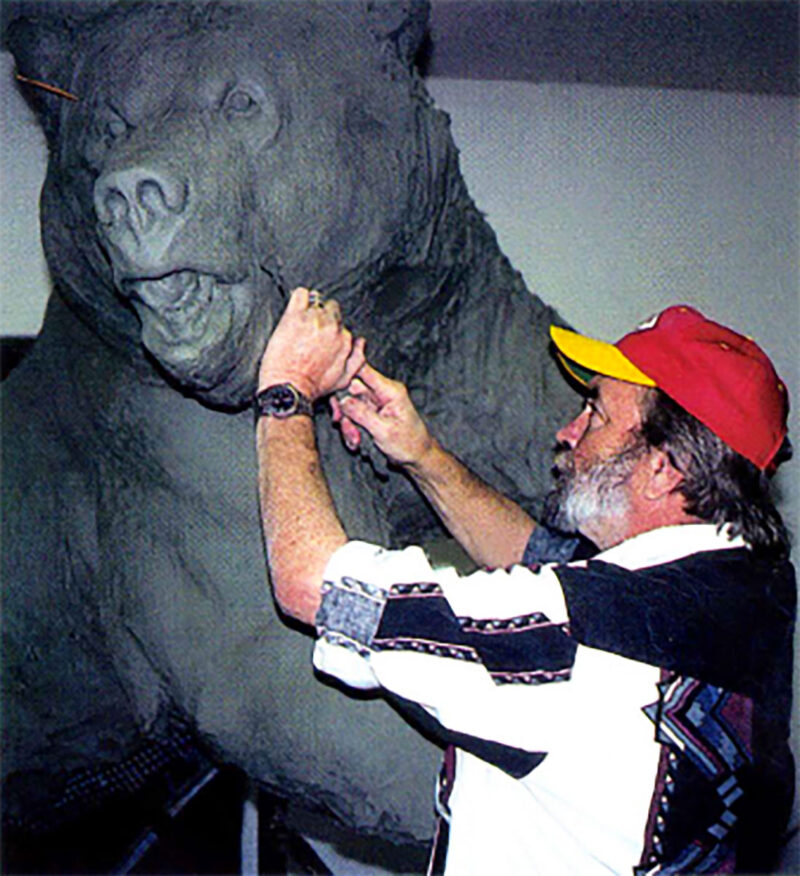

I visited Dennis at his studio outside Collins, Missouri, just a couple days after a fall turkey hunt in the Show-Me state. The Anderson studio is a rectangular, chocolate brown building with a bland exterior indicating not even a hint to the magic Dennis works within. The interior resembles a machine shop, with a decor that would scare some art patrons. There are stains on the bare cement floor, rugged, handmade tools lying about, grotesquely twisted steel armatures, a wicked-looking arc-welder hooked up to a 220-amp power supply. And Dennis is dressed for business, too: worn jeans and t-shirt, scuffed shoes and a baseball cap. While the stuff he makes is pure art – meant for displaying the finest homes, galleries or museums – the place he creates it smells like an auto mechanic’s stall and feels like somewhere you’d go to grind out a blue-collar, honest-to-God, 40-hour work week.

“Yeah,” Dennis laughs as he looks around. “I could work on cars in here and have less oil on the floor. There is motor oil in that clay, you know. A little wax, some axle grease, a bit of mineral oil. You have to work hard to get your hands clean at the end of the day.”

Dennis Anderson, 58, works on a heroic, seven-foot-tall version of Missing Lunch.

At 58, Dennis Anderson is lean and wiry, with intense eyes that seem always on the move. He walks with a limp, partly due to severe arthritis in his hips, but also as the result of a boating accident years ago that cost him a couple toes and part of his heel on one foot. “I was towing a kid in an innertube when we just hit a big wake from another boat. I pitched overboard and I dove as the boat circled around. I got my head under, but my foot wasn’t so lucky.

“Ironically, the accident was the catalyst for his sculpting career. Already an accomplished painter, Dennis received some modeling wax from a friend who urged him to get at it.” ‘You have no excuse not to try this now,’ he told me,” Anderson remembers. “So I just started groping around with it. I guess that’s alii do, even now.”

Anderson’s modesty belies the depth of his talent. Growing up near Seattle, Dennis realized at an early age that he had a gift. “I guess I knew by the time I was six or seven that this is what I’d be doing,” he says “But I never did well in art classes until I got into college, and I think it was because I never had a teacher who was as good as I was. Don’t take that the wrong way; I just don’t think the really talented artists were teaching then, at least at those levels.”

Miniature of Missing Lunch.

The budding artist did lay a foundation for his career by exploring the wilds of the Pacific Northwest. “We did a lot of fishing when I was young, hiking into remote rivers that had wild salmon and steel head. There were big crowds on the streams with hatchery fish, even then. But we weren’t interested in those places. We went to the wilderness rivers where, if you caught a couple of steelhead in a year, you were doing pretty well. We tied our own flies, just hunks of rag tied to a hook with copper wire. The fish were naive, but there just weren’t that many of them. We didn’t care, we just wanted to be where the wild ones were.”

He accumulated other experiences as well: bugling in bull elk with homemade calls of bamboo, hunting ducks on the flats and watching countless bears as they fished alongside him. “I watched a lot of bears over the years,” he recalls. “They were basically pretty docile creatures, but they never really did what you’d expect them to do. I guess I kind of think like one.”

When Dennis was a junior in high school, his family moved to California, where he finished high school, some junior college, and two years at The Art Center School of Pasadena. “Then some friends and I decided to go up to Seattle to see the World’s Fair, and when it was over, I just stayed,” he says. “I worked in a dental lab, making false teeth. That’s kind of sculpture, you know. They use wax to make impressions, and then a casting process Hey, lost wax is lost wax!” But Dennis was not going to make teeth for a living, and he eventually moved back to California, where he worked for the Navy as an illustrator before signing on with Hallmark and moving to Kansas City. There he designed book jackets, magazine covers, textbooks. “Saturday Evening Post kind of stuff, but it didn’t pay nearly that well,” Dennis says. “I quit after a while and did some freelance work for them. When I got a bellyful of that. I went into the painting thing.”

The “painting thing” was a chance for Dennis to strut his stuff and explore the subjects that he wanted. “I liked the shape and mass of big animals,” he says “Not that there isn’t something appealing about rabbits and kittens. But not done the way I’d been doing them. Hallmark was a good place to work, for a big corporation. But I’ll tell you one thing, they sure cured me of cute!”

Dennis may have remained content as a painter for a good many years, but like many artists, the business of selling art was not nearly as satisfying as creating it. “I never had a printing house, like a Hadley’s or a Greenwich, distributing my work,” he says matter of factly. “They have a marketing network that’s pretty remarkable. They’ll distribute prints to 500 of their dealers just like that. When I printed one of my paintings, I didn’t know 500 people who I could give one to!”

Should Have Been Here Yesterday

“I was moderately successful as a painter. But I think I’m better suited to sculpture — it’s more tactile; I get to use my hands more. You can attack a block of clay, whack off pieces of it and put them back on. I guess I use that approach while painting, too. You can look pretty peculiar at the end of a day [of painting] like that, and the canvas can get pretty heavy by the time you’re done. Sometimes you’ve got to take a sander to it just to thin it down a little!”

Making the transition from flat art to three-dimensional work was easy, according to Dennis. “You just look at a sculpture as a multitude of paintings,” he says, motioning to each quarter of a striking, finished bronze of a wolverine. “This is one painting, this is another, this is another. And the great thing is, you don’t have to put in a pretty background or a striking sunset. Seriously, though, 200 years ago, every artist did both.”

Dennis dove into sculpture, setting up shop near one of his foundries in Loveland, Colorado. Back then, he was among the small group of sculptors who established that town as a mecca for fans of bronze. While Dennis found the camaraderie of other artists enjoyable at first, he soon shied away from the tightness of the community. “It got to be an almost incestuous relationship after awhile,” he remembers. ”I’d see someone taking a little [idea] from someone here, and little more from someone there. You get some unconscious imitation, and some that’s more deliberate. After a time, I just had to find my own isolation booth.”

Indian Lake

Dennis found that isolation in Missouri, where he setup a studio and where he could put clay together and rely on his own outdoor experiences for inspiration and reference. “The great things that hunting and fishing do for you is make you think like a predator. And you also begin to think like the animal you’re after,” Dennis says of his sporting experience. “Anyone who’s caught a trout has had one wriggle out of their hands. So think of a bear that’s caught one and has it slip out of his grip. It’s easy to put yourself in his place.”

Keen observation is the cornerstone to emotion-filled art, he insists. “For starters, anyone who says they’re not using photos for reference is full of it. You simply have to. And sketch pads are another good tool. But if you’re married to either one of them, you’re keeping your head down for at least half the time and missing most of the action. I’m convinced if you really want to see how something behaves, leave the camera and sketchpad at home and bring along a tape recorder.”

Intent on capturing and feeling, Dennis’ style is loose and impressionistic, reminiscent of great painters like Bob Kuhn and Carl Rungius. He refers to them both frequently when talking about the kind of art he admires. “I think Bob Kuhn was trying to teach me everything he knows without knowing it,” he muses. “I admire tighter work, if it’s designed well. But achieving the same results with a looser style puts a high price on every move you make. I like to compare it to golf. If you’ve got a 180-yard hole to play, and the par is 18, you can play the entire hole with a putter. But make that hole a par-four, and you better choose your clubs right and make every shot count.”

Horn of Africa

Gordon Smith, who represents Dennis and collects his work, refers to Anderson’s bronzes as “sculpture with attitude.” “Dennis identifies with big, powerful animals; the bold and the dangerous,” Smith says. “But he shows you some nuance of them that you’ve never seen. It’s like he knows we have some preconceived notion of what a certain animal is, so he doesn’t bother with that. He gives you a glimpse of their temperament that goes beyond hair, teeth and claws.”

Smith, whose gallery has hosted the work of many artists, knows such perception is the rarest of gifts. “It’s definitely not something they teach you in art school,” he emphasizes. “That seeing beyond the obvious – the things that anyone can see – is something inside Dennis. So he’ll take some incredibly dangerous animal, like a bear, a Cape buffalo, a lion . . . something that could eat you for lunch, and put it in an amazingly innocent position. He isn’t going to bore you with details you already know.”

Over the course of our interview, the artist was usually warm and congenial, elaborating on some points like a teacher talking to a student, but other times almost terse in his response to my questions. A week later, Cordon Smith shed some light on Dennis’ personality with two stories, both of which occurred at a Game Coin International Show in San Antonio in the early ’80s.

Dennis was attending the popular exhibition for the second straight year when a couple approached him, mentioning that at the previous show they had considered buying his painting of two bears locked in savage combat, yet had decided it was too violent to hang in their home. Unsettled by their reasoning, Dennis’ response had bordered on being rude. “But we’ve already purchased one of your paintings this year,” the man explained, then added: “Will you be nice to us now?”

Morris

Over the first two days of the same exhibition Dennis had noticed a young boy lingering near his booth. Finally, the artist asked the youth why he was hanging around and the boy said, “I really like that picture of a leopard, but my dad won’t buy it for me.” Dennis told the boy to come back after the show and if the painting wasn’t sold, he could have it. The leopard painting failed to sell, and Dennis lived up to his word.

As our conversation comes to a close, Dennis’ wife, T.C., and their four-year-old daughter Lydia arrive in the studio. Lydia carries a children’s book, an illustrated ABC primer where each letter is represented by an animal. She cuddles close to Dennis, opening the book and flipping the pages, proudly announcing the name of each animal as it appears. Dennis nods patiently after each critter, obviously proud of her ability. After they leave, he will tell me “every time I work on an animal. I’m appealing to the child in all of us. Not the innocence we say they have, but their way of looking at things. They hate to be talked down to, even when they’re four. I have a big piece outside the Topeka zoo: a twelve-foot African lion. Kids play on it and get up and crawl all over that thing — in my book, that’s the best patina of all.”

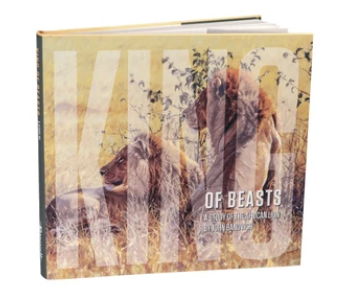

Following best seller and award-winning book “Beast” we are pleased to announce the release of “King of Beasts” by John Banovich. Featuring 208 large format pages, “King of Beasts” illustrates the dramatic artwork of John Banovich, all focused on depicting the extraordinary African Lion. An internationally recognized artist who has studied lions for decades, Banovich has selected a body of work that pays homage and explores questions about mankind’s deep fear, love, and admiration for these creatures.

Following best seller and award-winning book “Beast” we are pleased to announce the release of “King of Beasts” by John Banovich. Featuring 208 large format pages, “King of Beasts” illustrates the dramatic artwork of John Banovich, all focused on depicting the extraordinary African Lion. An internationally recognized artist who has studied lions for decades, Banovich has selected a body of work that pays homage and explores questions about mankind’s deep fear, love, and admiration for these creatures.

John Banovich believes he was born to tell the lion’s story—from its ancient past to its troubling future. And on these pages, he tells that story the best way he knows how—by painting it. Buy Now