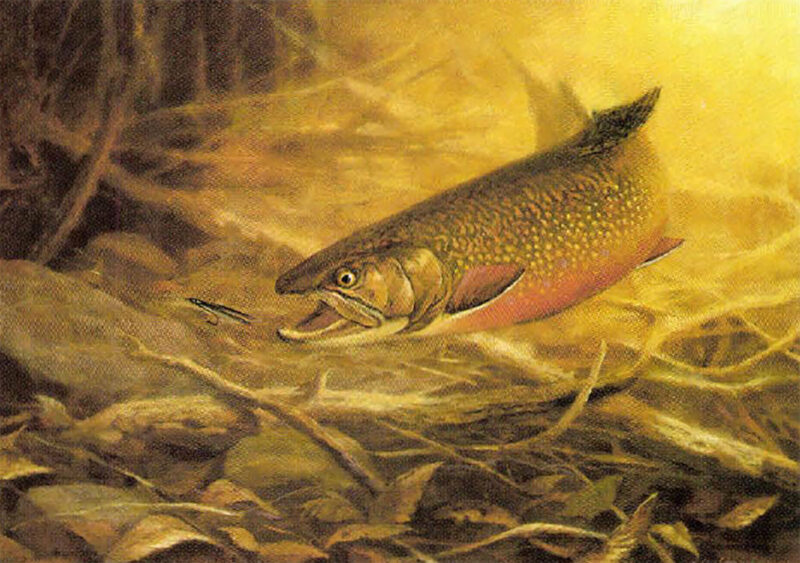

In many ways John Hamberger was more an impressionistic artist than a painter of fish portraits.

On the vintage plaster of the kitchen wall, left of the table where winter window light refracts through a collection of old pop bottles, is taped a snapshot of a man standing on the beach. He is staunch, feet spaced squarely and shoulder width apart. His face is broad and open, fringed with neatly trimmed white beard, and broken into a smile. Behind him the Atlantic, blue as it can sometimes be on a sunny day in early spring, laps more like pond water than ocean on the tawny sand. His right hand waves. Greeting? Goodbye?

On the vintage plaster of the kitchen wall, left of the table where winter window light refracts through a collection of old pop bottles, is taped a snapshot of a man standing on the beach. He is staunch, feet spaced squarely and shoulder width apart. His face is broad and open, fringed with neatly trimmed white beard, and broken into a smile. Behind him the Atlantic, blue as it can sometimes be on a sunny day in early spring, laps more like pond water than ocean on the tawny sand. His right hand waves. Greeting? Goodbye?

“That’s my dad,” says John Christopher Hamberger, dark eyes glistening with tears.

John Hamberger, one of the country’s most talented wildlife artists, died in June of 1999, in his quaint 1900s house in Chincoteague, Virginia. Divorce had chased him there – “He lost the big house but got the paintings,” John Christopher explains. Like a dozen other painters, sculptors and potters, John senior had found a kind of respite in this fishing village tucked behind a barrier beach at the base of Assateague Island.

Chincoteague leads a schizophrenic existence. Throngs of tourists crowd its streets, lured by Assateague’s gentle beaches and shipwrecked ponies of the island. They come for the annual round-up and sale of the little horses, made indelible by Marguerite Henry’s Misty of Chincoteague, that thin classic that remains a favorite for children worldwide. When tourists leave with the start of school, natives reclaim the town. Nearly everyone finds time during the day for a short walk on the beaches of the national seashore or the loop through the bayside wildlife refuge. John Hamberger would be among them, tan jacket open, a camera or sketchpad at hand.

At night you’d find him working in the front room, the parlor if you will, of the house on willow Street. Like stars swirling outward from a spinning galaxy, he’d spiraled tiny white Christmas tree lights from the old faux bronze fixture in the center of the ceiling. The result was an evenness of illumination not unlike the northern light favored by artists. He sat near the window and painted, two or three canvasses — a snowy egret contemplating a pair of moths, an Atlantic salmon brooding under a log, a rainbow leaping for a damsel fly — going at once.

At night you’d find him working in the front room, the parlor if you will, of the house on willow Street. Like stars swirling outward from a spinning galaxy, he’d spiraled tiny white Christmas tree lights from the old faux bronze fixture in the center of the ceiling. The result was an evenness of illumination not unlike the northern light favored by artists. He sat near the window and painted, two or three canvasses — a snowy egret contemplating a pair of moths, an Atlantic salmon brooding under a log, a rainbow leaping for a damsel fly — going at once.

Clammers from the rusty fishing boats tied to the short wharf near the drawbridge would see his midnight light and stop by, have a couple of beers and chat, interruptions that John apparently, welcomed more than minded. Glib and generous, he was a favorite on the island, particularly with single women, and according to one local artist, “He left a lot of broken hearts when he died.”

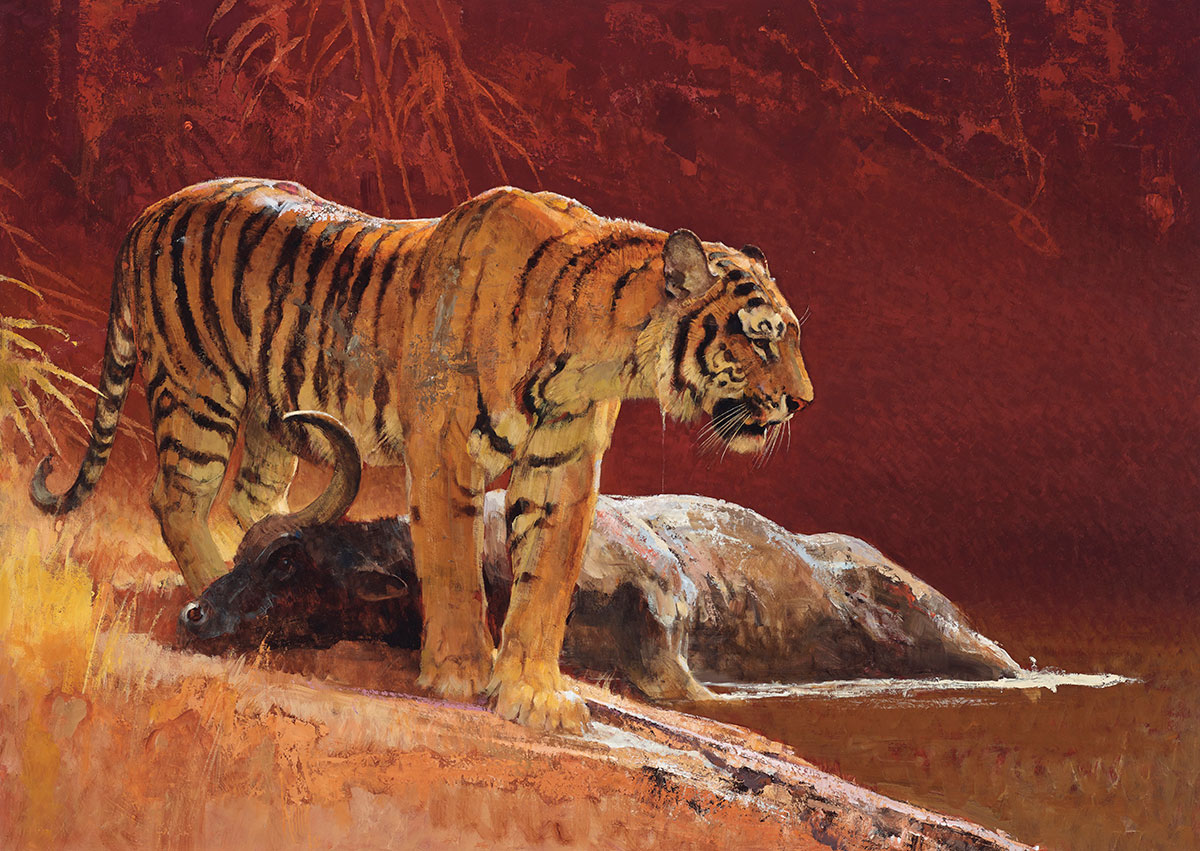

John Hamberger was a romantic, and you can see it clearly in his oils. His forte was painting fish in their natural environment, not ours, and his work has an ethereal quality about it. You feel as if you are suspended, floating, when you view his portraits of fish and for good reason. John fished, for sure, but he was not adamant about it. He’d rather pull on a mask and snorkel, and drift, weightlessly, observing and remembering and feeling what it’s like to swim with his subjects.

At times his works are passive. Looking at his pair of salmon beneath the limb of a tree, newly fallen into the river, you can feel their gills steadily pumping, open and close, open and close. Eyes ever alert, the fish seem to be at rest, at peace, content. The same is true of three tarpon holding smugly on the edge of a flat, mouths clamped shut, sun and wave shadow mottling their backs.

But that is not the case with most of his fish portraits. A largemouth surges from a weedy ambush trailing strands of moss as it closes on a red-and-white Daredevel. A Peacock and Yellow provokes a flashing-eyed Atlantic salmon to strike, a rainbow turns on a Mickey Finn just as it lands on the water. A striped bass rockets form the face of a wave, its mouth wide to engulf a glass minnow. Rapacious sailfish slice through a school of baleo in a dance that’s at once joyous and macabre.

But that is not the case with most of his fish portraits. A largemouth surges from a weedy ambush trailing strands of moss as it closes on a red-and-white Daredevel. A Peacock and Yellow provokes a flashing-eyed Atlantic salmon to strike, a rainbow turns on a Mickey Finn just as it lands on the water. A striped bass rockets form the face of a wave, its mouth wide to engulf a glass minnow. Rapacious sailfish slice through a school of baleo in a dance that’s at once joyous and macabre.

His works are not without whimsy. In a painting titled Trophies, a brown trout lies beneath a flat rock that snagged a pair of flies. A Royal Coachman hung in a bush draws a strike from a rainbow that rises like a missile from the shaded pond.

This man Hamberger knew his fish, not so much because he caught them with rod and reel, but because he studied them. “ Dad’s freezer was full of fish,” his son smiles. “People would bring them to him. Sometimes it was only the head.” Look at the detail in the eyes, jaws and gills of his fish. Just the way a portrait photographer adjusts the lens to focus on eyes and mouth, but soften the rest of the subject — so too does Hamberger. It’s an old trick, born in the days of glass plates and black focusing hoods, and a good one.

The settings are as realistic as the fish, but they’re rendered in a much more impressionistic style. If you want to know what the underside of a wave or lily pad looks like, you’ll learn from John Hamberger’s paintings. You can nearly feel the cobbles of his river bottoms through the soles of your wading shoes. The play of light on boulder and log is subdued, as if the water were slightly turgid with thin sediment washed in by rain.

If, from below, the view of the water’s surface resembles the scape of a troubled sky, it’s because he’d photograph roiling clouds so he could remember the interplay of texture and motion and use them later when he needed them. He’d shoot landscapes and turn the prints upside down to better understand the inverted world. And when his paintings weren’t going quite right, he’d hang them by their sides or bottoms for a few days and ultimately a solution would reveal itself.

In many ways John Hamberger was more an impressionistic artist than a painter of fish portraits. He would not set out to do, say, a brown trout. Rather, he’d want to try a new composition of submerged shapes, and into it a big kype-jawed male would swim. His subjects included everything from deer to bobcats to birds and even monkeys. Not the kind of guy to knock out painting after painting, John sometimes took months to complete a canvas and he found himself always living on the edge.

Born in the Bronx in 1934, John always claimed that he knew he wanted to be an artist from the time he was seven. His parents owned a small farm near Pine Bush in the Catskills of New York, where they spent their summers. John fished and prowled the woods and the landscape became a part of him. His urge to paint was, to him, like a calling to the priesthood.

What training he had was that of an illustrator who freelanced for a living. That’s his longhorn bull on Big Red chewing tobacco. Like so many freelancers, John doggedly pursued agencies and publishers for assignments and eventually, in the late ’50s and early ’60s, they came. He illustrated books — scores of books — for Readers Digest, Prentice Hall and Scholastic. His wordless The Lazy Dog is considered a classic by educators who use it to teach children to read. (OK, how do you use a book without words to teach reading? Children look at the pictures and make up their own stories which they then write down.) You can still find copies of MacMillan Book of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Creatures that he illustrated. An otter chasing a rainbow graces the cover of Boy’s Life in April of 1961.

Thinking that he’d try a full-time job to even out his earnings, John joined a commercial studio, but quit after half-an-hour. Too confining, he said. For 25 years he turned out drawings, sketches, posters and paintings of mostly natural subjects. And his earnings kept the wolves from the door.

Yet he yearned to paint because his mentor, Bob Kuhn perhaps the wildlife artist of the past century — had told him he had talent. During his lean, mid-20s, Hamberger had twisted somebody’s arm at Outdoor Life to fork over Kuhn’s phone number. Never short of chutzpah, John wangled a couple of hours with Kuhn who reviewed his portfolio, offered some suggestions and set the young artist off in what must have been the right direction.

In the 1970s and 80s, John Hamberger hit his stride. A show at Beaverkill Angler in Roscoe New York started him on the exhibition trail. His painting of a coho salmon is permanently displayed in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. He did a set of eight postage stamps featuring endangered species for the World Wildlife Fund. His paintings graced Field & Stream and Outdoor Life. He was elected to the board of the Society of Animal Artists and served on its jury for admissions. His works were sold at Abercrombie and Fitch back when it was the finest outdoor emporium in America, and in numerous galleries in other cities. By the late ’80s, he was riding the wave.

Back in Pine Bush, John remodeled the floor of his home and turned it into the Pine Bush Arts Center. For reasons clear to no one, he called the sales space “Bison Gallery” and there exhibited his and the works of other S.A.A. painters including Bob Kuhn. He taught classes and sold art supplies, traveled and painted and the years were good.

“John and I met at an art show in Palm Beach about tenor twelve years ago,” remembers Bill Turner, founder of Turner Sculpture in Onley, Virginia. “John was a great guy I loved his attitude and his work, and I guess he felt the same way about me.

“John and I met at an art show in Palm Beach about tenor twelve years ago,” remembers Bill Turner, founder of Turner Sculpture in Onley, Virginia. “John was a great guy I loved his attitude and his work, and I guess he felt the same way about me.

“His paintings are calm and soft and pleasant to look at — not the meticulous style you see in so many artists today. Yet he captured everything about the fish or animal, but without detailing every scale or feather. That’s the secret to being a really good artist. John was also very versatile. He could work in all kinds of mediums, and he was comfortable with almost any kind of subject matter.”

Though gifted artistically, John was never very adept with money and the mid-’90s found him in the throes of financial crises and divorce, and in search of a new venue.

“I suggested that he take a look at the Eastern Shore of Virginia,” said Turner, “and he eventually settled on Chincoteague. John was only 30 miles from our gallery, and he’d occasionally come over and help me with my painting technique. He would always joke that I should skip working in bronze and concentrate on painting.”

In March 1994, John moved into the little house on Willow Street. Here too, he taught classes, and according to Bill Turner, he was very good at it. Yet, artist’s block plagued him — sometimes for an entire season. “He needed to feel it,” says son John Christopher.

In March 1994, John moved into the little house on Willow Street. Here too, he taught classes, and according to Bill Turner, he was very good at it. Yet, artist’s block plagued him — sometimes for an entire season. “He needed to feel it,” says son John Christopher.

His paintings brought thousands, but tourists mobbing town every summer could seldom afford such fare. To capture a slice of vacationers’ dollars, he turned to making custom jewelry from salvaged gold and silver, and plaster relief casts of birds and fish found in the refuge and its waters. He called his digs Ark II, as if it were a second vessel of safety.

John had again returned to painting just before the end, and his work was better than ever. He was promoting his art in galleries, and Sporting Classics’ editor (at the time) Chuck Wechsler had called to arrange a profile in the magazine. John was well into a crash diet to lose weight. His easel held the picture of the egret and the moths, almost completed. Anticipating a visit from John Christopher, he’d laid in a stock of ribs and some beer, a favorite supper of theirs. When John C. called to postpone his visit, his dad decided to eat the ribs before they spoiled. That June night he died.

John Hamberger is remembered as one of the finest wildlife artists of the 20th century. His gamefish project a vitality uncommon among the works of other painters. There’s a richness of hues, a depth of feeling and an uncanny energy that draws your mind into the picture. You’re there in the river with the fish contemplating the fly. Will you take it?

World-class angler, diver, photographer, and artist Guy Harvey shares his signature artwork, knock-out photographs, and fascinating stories of his time on and in the waters of the world. From Alaska to Australia to the Galapagos and beyond, Guy takes us along on the international fishing experiences of a lifetime.

World-class angler, diver, photographer, and artist Guy Harvey shares his signature artwork, knock-out photographs, and fascinating stories of his time on and in the waters of the world. From Alaska to Australia to the Galapagos and beyond, Guy takes us along on the international fishing experiences of a lifetime.

This strikingly beautiful, large-format book showcases Guy Harvey’s around-the-world fishing and diving adventures. Drawing from meticulous notes, knock-out photographs and Guy’s signature artwork, Guy weaves together fascinating stories, scientific discoveries and insights into the behavior of dozens of gamefish species to give us an up-close picture of his time on and in the water. Buy Now