May 1979

Ethiopia, much like Nicaragua, ain’t what it used to be. It’s the same problem of Marxist incursion that has so altered life there that the country I knew really was a last horizon.

There is still safari hunting in Ethiopia, but I think things have a very different flavor than they did under the management of the late Emperor Haile Selassie. In the time I spent there, I came to understand that the old Abyssinia was always unique when compared with the rest of East Africa, such as Kenya and Tanzania. It had had home rule for some 3,500 years and was far more dangerous than the usual safari areas to the south because of the great shifta or bandit activity along the borders with Somalia, Kenya, and Sudan. It was along this southern Ethiopian border area where I hunted.

This chapter is taken from my first experiences in Sidamo Province, and at the risk of sounding too Indiana Jone-ish, I think that the three of us involved were lucky to have gotten home at all.

Christian Pollet sat close to the dying thornwood fire with the shotgun cradled in his arms. He had been thinking about the cigarette for a long time now, forcing the thirst from his tired brain with the imagined aroma of the single smoke left in the tattered, sweat-stained blue pack. If he thought hard enough about how the smoke would slide, strong and smooth, into his lungs on the first drag, he found that he didn’t notice quite so much the thin, icy wind that razored through his flimsy cotton bush jacket, or the chill from the ancient sands that penetrated into his desert boots and bones like winter swamp water. He placed the butt between his cracked lips and let it hang there unlit. He knew he wouldn’t light it – it would only increase the torture of his thirst.

As I lay on the other side of the fire watching him, he pressed the action-release button of the pump gun and slid back the action an inch. The brass base of a red plastic shell – an ounce and a quarter of 7 1/2s – gleamed gold against the blued steel of the Winchester Model 12.

“Well,” I whispered, “we’re in great shape to hold the fort against a couple of marauding quail, but I wouldn’t want to tangle with anything much bigger with these popguns.”

Pollet wrinkled his face. He jerked his head toward the little Model 70 .270 Winchester propped near him. “Yes,” he answered in his Gallic accent. “I know what you mean. Want another piece of last week’s warthog?”

“No thanks, too dry,” I said. Besides, the piece of pig hanging nearby was reaching a state of advanced aroma. “When shall we drink the beer?”

Chris picked up the previous can and glanced at the label. It was written in the strange symbols of Amharic, the prevalent language of Ethiopia. “The Champagne of Panther Pee,” he translated freely. “Not for Internal Consumption.”

“Don’t make me laugh with these cracked lips, chum,” I told him. “Here we are in the lap of primitive luxury, free from all the complications of the civilized world, our blessings replete – nay, bounteous – with a cigarette and a can of beer, not to mention the finest aged warthog ham in Sidamo Province. You know what warthog sells for in New York? I don’t either, but it must be plenty. Appreciation, that’s your problem. No appreciation for the simple, lusty life. Fresh air and exercise. Look at all the weight you’re losing!”

Pollet folded his hands under his chin. “Do you suppose I could have it copyrighted as Dr. Pollet’s Diet? You know, no water and all the warthog you can eat?”

“I doubt it,” I told him. “With Cleveland Armory lurking put there somewhere, there’s bound to be a Save the Warthog Federation.”

He nodded glumly and stared past me into the world of bush-twisted blackness beyond the campfire’s glow. I noticed that his expression had changed, his eyes narrow and his head cocked. “Did you hear that, Peter?”

“Hear what?” After even a moderate lifetime of muzzle blasts without proper protection, I have the hearing of a fireplug.

“Dunno. Listen.”

As I strained, a sound came softly from the darkness, the light swish and rack of dry bush seeming to emanate from 50 yards downwind. I felt the same stirring in the pit of my empty stomach that a Neanderthal must have experienced at the scratch of powerful claws at the entrance of his cave. I suspect you know the sensation. It is called advanced apprehension.

“What the hell is it?” I whispered.

Pollet’s jaw muscles drew up into round walnuts as he stared me in the eye. “Elephant,” he said flatly. “Wake up, Karl.”

I nudged the Swiss professional hunter who came instantly awake with a questioning look on his rugged face. He, too, listened as Chris pointed wordlessly and the sound moved closer, then stopped. “With this wind he sure as hell knows we’re here, but he doesn’t seem to be moving off. Maybe a lone bull with a toothache or something.”

A screech like a speeding train with locked brakes made me jump involuntarily a foot off the ground. “Oh-oh,” Pollet moaned. “We got trouble, boys,” He grabbed the .270 and slapped the shotgun into my hands.

“Chris, don’t belt him with that Peashooter!” yelled Karl. “That little bullet doesn’t have a chance of stopping him!”

“Stop him?” Chris shouted. “I won’t even be able to see him until he’s in the firelight! Get on the far side of the fire, and if he charges, Peter and I will run left, you right, cutting the wind. Maybe we can dodge him. If worse comes to worst, meet back here at dawn.”

I ran over to the far side of the clearing as the crashing of bushes grew closer. I had never even seen a wild African elephant, and it was beginning to look like my first close-up might be my last. The big – at least he surely sound big – bull was cutting loose a charming series of burbles, gurgles, and roars so loud I could feel the vibrations in my chest. I was frankly frightened motherless, afraid to run and afraid not to.

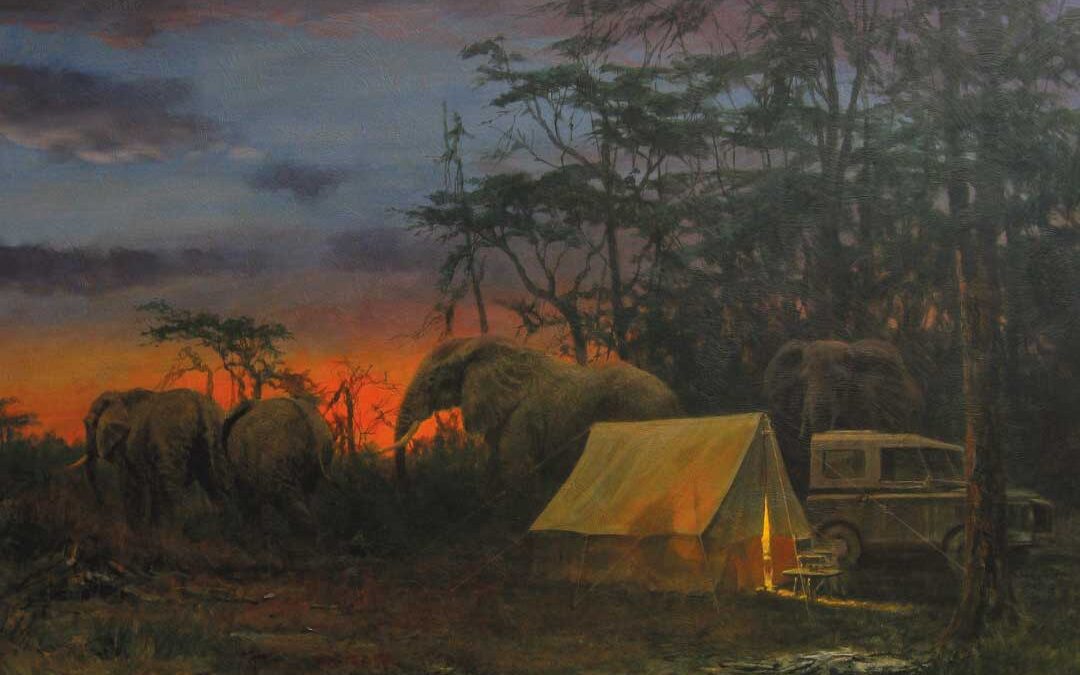

Night Terror by John Seerey-Lester

Karl began to shout some very nasty things and clap his hands. The elephant couldn’t be more than 15 yards away now, just starting to loom as a mountainous shadow. He howled for me to fire the shotgun over is head, and I pumped off two quick rounds. There was instant silence. The bull had stopped. Then he began to blow low, foghorn notes, almost a mutter of confusion. Maybe he had changed his mind about whipping up a batch of people-burger. I most definitely hoped so.

I could hardly hear Karl whispering to me over the thump-crashing of my heart, now wedged just behind my second molars. He was telling me that the bull was moving off but would probably be back. I heard the sounds receding until they stopped 40 or 50 yards away. I looked over at the small, metallic sounds Chris making with the Winchester and came to the immediate conclusion that he had lost his mind. He was unloading the rifle!

“What the hell?” I asked him incredulously. “Have you gone off the deep end? That’s an elephant over there that’s trying to eat us or whatever! What we don’t need is an empty rifle!” He looked at me and continued ejecting the 150-grain soft points.

“Nope. If you can keep that thing off my neck for five minutes or so, I may be able to rig something to stop him.”

“Look,” said Karl patiently, “you just can’t run around shooting elephants with .270 softpoints. It tends to make them very angry. It will make this one especially angry because he’s already in a very poor frame of mind. I say the best bet would be to try to blind him with the shotgun, run crosswind and hope for the best.”

“Tell you what, Karl,” said I, offering him the shotgun, “If he comes again, you take him and I’ll go look for another. Okay?”

Chris ignored us, fiddling with a cartridge and digging around in his pockets. I turned to face the blackness where the elephant was now probably deciding whether or not to make our little group a foursome. As the seconds ticked by, I wondered vaguely to myself what in the world I was doing here, freezing, dying of thirst, and about to be stomped into furry pink Jello-O in a land that was already hoary with history before King Solomon and his Merry Band pried their first diamond from her rugged surface . . .

Chris and I shared bachelor digs in New York back in the ’60s and worked together for the safari division of one of the big arms companies. Chris had spent 20 years in what was then the Belgian Congo, earning the same sort of reputation as a professional hunter that Joe Louis had pounded out in the ring. Upon arriving from Belgium, he had started off with Pan American, but gradually had fallen prey to the independence and adventure of the safari business.

Before he had to leave in 1960, during the late extreme unpleasantness of the “Simba” uprisings, he could count among his clients such men as Lowell Thomas and Belgium’s Grand Duke. As for myself at this time, after a few years in Central and South America as a professional jaguar hunter, I had a positive rash to see Africa and jumped at the chance to check out hunting quality in southern Ethiopia for the company with Chris.

“Ethiopia is a weird joint,” Chris had told me, “and the first thing you will notice is that Abyssinia was the perfect old name. It is 99 percent vertical, and most of it’s still as wild as the rest of Africa was five hundred years ago. It’s been free, black, and under the same management for something like 3,500 years now, and Hailie Selassie claims direct descent from the Queen of Sheba. It still has quiet slave trading and shifta gangs – private armies of nomad bandits that specialize in castrating infidels. Pretty tough real estate down around Sidamo Province, bordering Kenya’s Northern Frontier District, which itself is now closed to hunting because of shifta.

Our area is known as Borana, after the Boran, toughest of the local bad boys. It’s probably because the place is so rugged that it still has a hell of a lot of game, or at least that’s what Karl Luthy tells me. He’s a Swiss, but he’s been down in Borana for about ten years, hide-hunting crocs on the Dawa River. If the shooting’s as good as it sounds, the company wants us to sign him up for exclusive representation in the States.”

“Okay,” I agreed. “See you in Borana, Bwana.”

Our Ethiopian Airlines jet swung over the field at Addis Ababa and settled to the asphalt like a huge, pregnant vulture. We had met Karl Luthy in Monte Carlo at a game-conservation conference, and he had flown back to Addis with us. He waved to his pretty wife, who stood waiting by the door marked with the Amharic equivalent of Customs, and led her over to meet us. It would only be a matter of a few minutes’ formalities to get our gun certificates, she assured us, but two hours later we were still standing there. The official who had to approve the approval of the approval of the first two officials had gone to dinner. Tomorrow was Coptic Christian Christmas, January 7. Wouldn’t we come back in three days, please?

Karl explained that we were leaving on safari the next morning and probably would not fare too well without guns, so how about it? Sorry, the official had gone. Back in three days. No guns. The clerk walked off.

“Well,” said Karl, with the helpless shrug of any long-time resident of an African country, “E.W.A.”

“What?”

“E.W.A. Ethiopia Wins Again.”

On the third day we were back at the airport, mightily girded with righteous indignation and quite a few American dollars in small, easily digestible denominations. No, the officer was not back yet, said the clerk. Was he certain, Karl asked, flashing a wallet that looked like part of a cabbage patch. Ninety dollars later we were on our way. With the guns.

An hour later we spotted the whitish smudges of smoke faithfully tended by Karl’s staff at his strip. The landing was surprisingly smooth, and we hauled up in the midst of a murmuring gang of Galla and Gherri tribesmen, most of whom looked at the aircraft as if trying to decide the easiest way to clean it. A zebra-striped Jeep rolled up. I half expected Stewie Granger to step out, but it was a kikoy-clad Moslem gunbearer named Ahmed who shook my hand.

On the way to camp, the Jeep crawled to a halt and Karl began to study a distant patch of bush through his binoculars. I also stared through mine, but the late-morning heat mirage was too severe to make out much. “Very nice gerenuk over there in that patch of scrub,” muttered Karl. “We could use some camp meat, so let’s take a swat at him.”

“Great idea, but what in hell’s a gerenuk? I asked.

“Long-necked antelope, sort of a trial-size giraffe without the markings. Sometimes call them Waller’s gazelle. Have a funny way of feeding on their hind legs.”

“Lead on, Lawrence of Abyssinia, I’m fair mouth-watering for home-cooked gerenuk.”

Ahmed opened one of the hard cases and slapped me the .270, having won the coin toss for first shot with Chris. I unscrewed the tension toggle of the detachable scope, as I hadn’t been able to re-zero and would be better off with the iron sights. I didn’t want to blow my first chance at African game. Karl nodded and began to lead off in a low hunch through the thorny scrub and lion-colored grass.

After 150 yards, we began to crawl, my thoughts mostly on the really neat assortment of cobras, mambas and various adders I envisioned behind every third tuft of grass. Karl stopped short and held his hand behind him in the halt sign. He turned and barely whispered “Uh-oh. He’s spotted us and is looking right at us. Just head and neck showing. Not much of a shot . . . want to try it?”

“What the hell? I shoot all my gerenuks through the neck. Only way.”

I sneaked a few feet ahead and slowly rose, slipping my elbow into a ready-sling. As I lined up the sights and began to squeeze off, there was a flash of movement as the animal turned and began to bound away to the right. I swung the sights a yard ahead of the neck and touched off. There was a bang and a whock and the gerenuk disappeared.

Karl slapped my shoulder as Ahmed came loping through the grass from behind us, headed for the fallen animal, his knife tight in his fist. When we came up, he had cut the throat with a deft whip of the blade.

“Was that necessary?” I asked Luthy. “He must have been stone dead before he hit the ground.”

He shook his head. “It’s called hallal. Most of my men are Moslems. Unless the throat of an animal has been cut by a Believer, they can’t eat it. It isn’t really supposed to count unless the game is at least a little bit alive, but these chappies get fair starved for red meat between safaris and cheat now and then.”

From the hill overlooking it, Karl’s camp looked like Saladin’s winter quarters. The tents, each of a brightly dyed native color, were nested like fantastic toadstools on the grayish banks of the Dawa River, each tucked neatly beneath fluffy green trees. His staff was pulled up into a neat rank to greet us. Luthy ran a tight camp. It was not very long before I wished I had never left it.

Over gerenuk á la milanais in the screened-in dining tent that night, we discussed our operation plans for the safari. This being my first African trip, I was most interested in members of the “big five,” the stuff that bites back. Rhino were protected in Ethiopia, and lions were usually encountered as a matter of routine chance. Buffalo were located farther downriver, so we logically started the campaign on elephant. Karl said that they were not overly numerous in the area, but some really fine old tuskers did come across from Kenya, and there were normally a few to be found with hard work.

Between us, we decided that our best bet for jumbo would be that which gave us the most mobility if we could cut a big spoor, and therefore we opted to travel light in just the Jeep, without a gunbearer. Blankets, food and water – of course with appropriate additives for the traditional sundowner or two – would be the extent of our comfort for the next several days – or so we thought at the time. Karl reckoned that a water hole some 50 miles upcountry, known to be used by elephant, would be the logical place to begin checking for activity.

False dawn found us finished with breakfast and hunched against the cutting wind of the open Jeep as we sped at a dizzying ten miles an hour along a game trail into the barren, rocky hills. A few times along the way we stopped to ask nomadic Somalis and Boran if they had seen any elephant.

“Oh, sure,” they would invariably reply, “thee are slathers of them just a few miles ahead, all with teeth like big, white trees.”

Karl dismissed most of the information, telling me that the local theory was that even if they hadn’t seen a jumbo in six months they would say they had and should we kill one, then claim the customary reward for “directing” us to the bull. Larceny is an advanced way of life in Ethiopia.

The sun was high and hot when we reached the waterhole. It was a lovely spot, lined with cool emerald trees, the center of a spiderweb of game trails leading in from every direction. The only problem was that it wasn’t a waterhole any more, just a hole. A scorching December had left only a hint of subterranean moisture beneath the sands down the slopes, where there was normally a small stream. There were, however, several places where signs showed that elephants had shuffled and tusked their way down to the seepage a few days ago.

“Doesn’t look so hot,” mumbled Karl. “We can’t even get any water here for ourselves as I’d planned.” He looked over the tracks the size of garbage can tops that marked the perimeter of the area, noting that most of them seemed to lead east. “Let’s have a look fifteen or twenty miles over this way and see if we stumble into anything.”

We climbed back into the Jeep and began to weave through the thorn tangles. The “trail” twisted through miles of increasingly difficult country, the Jeep often leaning at hairy angles on the slopes. It was nearing dark when it happened.

We were edging along the grassy rim of a steep gully when the old roller-coaster feeling hit the pit of my stomach. At the same instant, Chris screamed “Jump!”

I threw myself into the air as the Jeep began to turn over, the loose soil at the edge of the ridge collapsing under the vehicles weight. It smashed down the incline for 50 feet, throwing gear and loose objects into the air with each flip, bashing itself into junk until it came to rest, upside-down, half-impaled on a rocky spine at the bottom. It teetered there for half a heartbeat, then burst with a whom! Into flame as gas from the ruptured tank met the hot engine.

Chris and I picked ourselves up and went to Karl, who was feeling his left arm for a possible break. It was swelling like a kid’s balloon, but didn’t seem fractured. Behind the wheel as he had been, he was damned lucky to get out at all, being thrown clear after the first bounce, happily not on his head. Chris was spending his spare time offering some very explicit opinions involving the ancestry and dubious origin of the dead Jeep.

The blackened car was crackling as merrily as a Yule log as we began to take stock of the equipment that had survived. Chris was looking at the smashed body of his camera when the first shot went off. We had forgotten the ammo in the glove compartment, 500-grain, .458 Magnums, .270s and shotshells all cooking off as we hugged the slope and prayed. Finally, certain that they had all detonated, we got sheepishly up. Nobody had been hit. Of course, there was little danger, I realized, as the cartridges were not confined.

“You know, old buddies and true, I think we’ve got a bit of a problem here,” I said. “Am I mistaken, or is it forty miles across this piece of hell to the Dawa?”

“More like sixty,” Luthy answered cheerfully.

“Well, let’s take stock of what’s left,” said Chris.

The modest pile of recovered gear didn’t look too encouraging. It totaled, miraculously, the .270 (which, although the scope had been knocked askew, seemed in working order), the shotgun, a hatchet, and, almost incredibly, two flax water bags that had been hanging over the mirror support and against the edge of the door. Checking our pockets, we filled out our cache with Karl’s big folding skinner, my Swiss army knife, two rolls of film, seven shotgun shells, five .458 rounds and seven for the .270. Chris had four cigarettes, I had two.

I considered throwing away the .458s since both rifles in that caliber, a pair of Model 70 Africans, were destroyed in their lashed-down rack by the fire, but figured that we had so little that anything might turn out to be useful.

We decided to rest where we were for the night, and start back at first light. It would have been impossible to travel through such terrible terrain at night, so Karl lit a fire while Chris went over the area for anything we might have missed from the car, returning with a dented can of local beer. I checked the radiator of the car on the remote possibility that the system might still contain some water, but it looked like an ax murderer had gotten rid of his frustrations on it.

The primary question was which route to take back to camp. The dry water hole was about 20 miles off at a tangent, and by the time we reached it, even the foul seepage might be out of reach. It would also mean an extra 15 or 20 miles of walking – perhaps for nothing – so we decided our best bet would be to push straight across country, trying to pick up the Dawa somewhere north of camp. We all knew that we could live a long time without food even if we were so unlucky as to shoot nothing, but also that the 110-degree days would kill us quickly unless we got to water soon. The two quarts of water and the can of beer we had wouldn’t last long.

As the blankets had been lost in the fire, we suffered in our light cotton bush jackets from the intense chill of the highlands despite the campfire, yet the first night went well. Karl insisted we keep a close guard, since Sidamo had a nasty reputation for man-eating lions (now he tells us!), yet but for two hyenas and an odd jackal, nothing disturbed us. We split the night into three watches, starting when the first man slept and ending with false dawn.

At first light, Chris shook me awake. I had drawn the middle watch, and now felt as though I had done 15 rounds with Marciano the night before, having more bruises and aches from jumping from the Jeep than I realized. We pushed off with the guns and water evenly distributed by weight. After three hours, we were about bushed from struggling through the wait-a-bit thorn scrub and alternately rocky and sandy footing up and down the torturous, never-ending gullies, hills and ravines. I guessed we’d made five miles, most of it vertically, but already I was dying for a drink.

The sun seemed to dry me out like a piece of jerky, and I knew that Chris, who had fairer skin, was really being fried. Recalling my paperback westerns, I sucked on a pebble to keep my mouth moist. Maybe it works for cowboys and Apaches, but it is notably ineffective for curing the thirst of one-time stockbrokers turned idiots.

Despite the hours of trekking, bitching at thorn cuts and scraped knees, we spotted no game in the arid country. Through the long, searing days, only the kites and king vultures kept us wary company, and only the hyenas by night, which made me wonder idly what the hell they did for water. I could easily have knocked down one of the big birds with the scattergun, but I wasn’t thirsty enough to try sucking the juices out of a vulture – at least not quite yet.

Thorn-studded, bleeding real blood and completely exhausted, we dropped in our tracks for the second night’s rest. We had not yet touched the water, and except for a one-hour break at the sun’s unbearable zenith each day, we had been constantly on the go. But it was now obvious that we had to use some of the precious water.

Using the small blade of the pocket knife, I pried open the crimp of a shotshell and removed the contents, and we each had three shellfuls of the delicious stuff. I drank the first two almost straight down, but held the other in my mouth for a long time, feeling the tepid liquid soak into the leathery lining of my parched tongue and cheeks. Chris and I split one of his remaining cigarettes, agreeing that nothing – and I do mean nothing – ever tasted so good.

Around the fire we three sat shivering, looking at the deflated water socks, each realizing that they were all that stood between us and a terrible, lingering death when we became too weak to go on. As we were now, when the water was gone it would only be one or two agonizing days before the hyenas polished us off where we lay.

I had a conversation with Chris and Karl about possible alternatives to a creeping death if we got too weak to move on, a chat that I prefer not to recall here. Officially, we would have simply disappeared, and considering the wildness of the region and the efficiency of the African sanitation squads, only the Jeep might ultimately be found. Things had looked brighter.

Two more days of pain-filled exhaustion followed as we plowed ahead by dead reckoning. I made up a little personal joke that if we were wrong in our direction, dead reckoning would be a wonderfully accurate term. Then, late on the fourth day, Chris nearly stepped on a warthog to which he administered the classic Texas shot with the .270. The late pig was in very poor condition and it looked like the “before” picture in a bodybuilding advertisement. Nobody thought it very funny. We squatted around the pig and tried to decide what parts to take, agreeing to eat the backstraps right here and carry one ham along the next day. Although it took most of what was left of the water even to be able to swallow the delicious stick-roasted meat, we all got a tremendous lift out of the gorging, despite severe stomachaches that slowly passed, and felt much refreshed the next morning. As we set off, Karl thought the river was probably about 20 miles away, not much of a walk for a fit person, but for three apparitions like us to cross the horror of ridge-snaggled bush, now down to about a pint of water among us, was something else.

That night, as we sat around the campfire, having been forced to finish the last of the water at noon to be able to get this far, the elephant came out of the darkness . . .

The brush began to crash again as the bull came forward in another threat display that might turn into a full charge at any second. My guts felt as if a covey of quail were trying to escape, fear weakening my knees. I’d looked at a lot of interesting things over the rib of a shotgun, but this was too bloody much! Then I decided the hell with it. If I’m going, I’m going down with all guns firing! Suddenly he burst into a ring of dull firelight and paused, then his trunk tucked up against his chest and his ears flared out like big, gray billboards. With an earsplitting scream he began to come at us, his heavy, mismatched tusks glowing eerily.

My first shot went almost unheard as I fired at his left eye with the shotgun, the tight pattern kicking up dust from the surrounding skin. He tossed his head, but never slackened pace. I was working the pump instantly when from alongside me came a flat whiplash of sound. I saw another puff of dirt between and just above the bull’s eyes. To my amazement, as if in slow motion, the bull’s head began to rise as his hind end collapsed in mid-stride. Like a gray mountain, he plowed to a halt of flying dirt, one tusk furrowing deeply into the ground six feet from the fire.

I stood mute, the shotgun still pointed at the fallen hulk, hardly realizing that, somehow, the elephant was dead.

But how? Karl was unarmed. I turned and saw Chris extract a spent cartridge from the .270 and carefully hand-feed another into the chamber. He walked around to the side of the bull and shot him twice more, low and just rearward of the foreleg, spacing the shots to be certain to hit the heart. Satisfied that the elephant was dead, he fished another cartridge out of his pocket.

Karl walked over and took it to the fire for examination. “Unbelievable,” he said, “absolutely unbelievable.”

I stepped over to look at the round for myself, still unable to believe that a 150-grain softpoint could kill an elephant by penetrating through the nearly three feet of spongy bone protecting the brain in the classic frontal position. Suddenly I realized what he had done.

What ever made you think of this, chum?” I asked him, handing back the round.

“I read about it ten years ago in an old book on elephant hunting,” Chris said. “When the ivory hunters used to run low on solid bullets, they would finish up the safari by reversing their soft-point bullets in the cartridge cases so they were fired base-first. Of course, penetration was greatly increased. Not much for long shots, but deadly at short range. Okay for an emergency, though. I figured we had an emergency.”

He felt the inside of his mouth with a forefinger. “Thought I was gonna break a couple of teeth getting them out of the cases, though.”

Chris fed the cartridge back into the magazine and, taking Karl’s hatchet, walked over to the elephant. Karl was bent over, examining a tusk. “Aha!” said the Swiss, pointing to the base of the right tusk. “Here’s why the old boy was looking for blood.”

I followed the point of his finger to the edge of the animal’s lip, where a half-inch black hole oozed pus from the huge tusk nerve.

“Musket ball,” said Karl in disgust. “Poor old bastard must have been insane with the pain in the root of his tusk.”

“Well, if we’re lucky he may have solved our water problems, anyway.”

I asked Chris what he meant.

“Elephants can store considerable quantities of water in the forward part of their stomachs, especially in dry country. From this old boy to be wandering around this far from water, he probably took on a load yesterday. I’ve seen them reach down their throats with their trunks and blow twenty gallons of water over their backs to cool down. First time I saw one do this, I figured he was sucking it up from a waterhole I somehow couldn’t see, but when he moved off, there was no ground water at all.

“Watch this,” he said, swinging the hatchet hard, the more cautiously for ten minutes. Switching to Karl’s folding knife, he continued to cut for some time, finally stepping back to wipe his gory hands on the ground.

“See that?” he asked.

I looked into the bull’s chest cavity and saw the side of a large, rubbery sack at what appeared to be the front of the stomach cavity. Chris took the knife and cut two strong thongs from the ear skin, and we were able to tie of the front and rear of the organ much like a knackwurst. With the greatest care, we sliced the sloshing, formless sack free of the carcass and laid it on a clean, smooth patch of sand.

Karl smoothed a number of sticks and sank them deep into the sand to act as a support for the sack so that it would not topple and the invaluable liquid escape. Tenderly steadying the apparatus, Chris made a smooth slice across the top, and there, a finer sight than emeralds, gleamed ten gallons of reasonably clean water, the still body-warm liquid steaming in the icy night by the light of a flaming brand.

With the water bags again bulging, we rested all the next day and night, despite the even worst cold. Finally leaving the carcass for the final walk out, we felt like new men, completing our escape just before dusk that evening.

By the best dead reckoning I’ve seen, Karl hit his camp right on the button. The description of the multiple joys of a triple Scotch, a hot bath, a whole pack of smokes of my very own, a breast of francolin snared by Ahmed, roasted a cordovan brown and accompanied by several icy bottles of Graves, is well beyond the ability of your obedient servant.

The tusks, abstractly and incidentally, weighed 64 and 51 pounds, and were later recovered by Karl’s crew.

Ethiopia did not soften her tricky ways the rest of the safari, and although I really did quite well in the trophy department, including a new world-record Peter’s gazelle (at the time), status returned to quo when the plane sent to pick us up for the return to Addis Ababa never showed and we were forced to drive the supply lorry all the way back, a feat not unlike jockeying the Queen Mary up Mount Everest in dry weather. Consequently, Chris – whom I greatly regret to tell you has since been killed in Africa – and I arrived back in New York ten days late. Reporting back to work the next morning, we were asked by an irate bossman why we were 11 days late.

“E.W.A.,” answered Chris.

“What?” asked the vice-president.

“Ethiopia Wins Again,” said Christian Pollet.

Note: Death in Sidamo first appeared in the May, 1979 issue of Petersen’s Hunting magazine and then in Last Horizons, published by St. Marten’s Press in 1989. It was reproduced in the 2012 September/October issue of Sporting Classics magazine courtesy Fiona Capstick and St. Marten’s Press.