I had an uneasy, anxious feeling as we drove to the bait tree just east of camp.

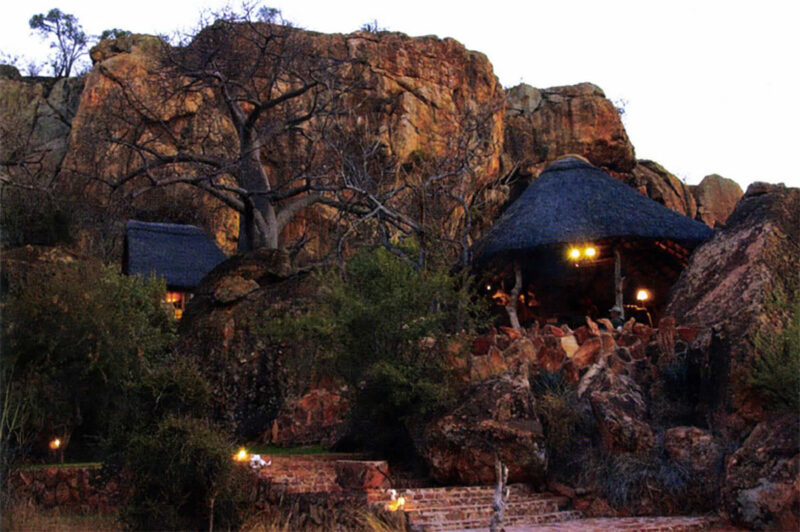

It was with a bit of apprehension that I viewed my trip back to Zimbabwe and a patch of hunting land I had come to know and love. Through my long-term partnership with property owner Digby Bristow, I had visited Sentinel Safari Camp on many occasions, taking a number of top-flight animals including kudu, bushbuck and spotted hyena. Political instability in the country had shut down hunting operations on the 80,000-acre concession for over a year, but the situation had improved somewhat and hunting had resumed.

It was with a bit of apprehension that I viewed my trip back to Zimbabwe and a patch of hunting land I had come to know and love. Through my long-term partnership with property owner Digby Bristow, I had visited Sentinel Safari Camp on many occasions, taking a number of top-flight animals including kudu, bushbuck and spotted hyena. Political instability in the country had shut down hunting operations on the 80,000-acre concession for over a year, but the situation had improved somewhat and hunting had resumed.

As a wildlife biologist and outfitter, I was interested in evaluating how Zimbabwe and its animals were faring, and discovering that answer firsthand is what united my friend Rob Lurie and me in a leopard blind just a few hundred yards from the Limpopo River.

Rob and I had originally met 10 years earlier; I was in Africa on my very first safari and he had come over from the neighboring camp where he was enjoying his first year as a professional hunter. We were both fresh out of school — Rob as enthusiastic as any apprentice PH I’d ever seen, and myself, a 24-year-old plantation manager in Georgia. We both thought we had died and gone to heaven in this wonderful land called Zimbabwe.

My, how times had changed, for each of us and for the country that we had come to love. Rob was now a freelance PH with his own safari operation, and I had become the managing partner of High Adventure Company, a booking agency and outfitter that operates lodges on three continents. Zimbabwe, on the other hand, had not been as prosperous.

Within a few hours after my arrival, I was confident that the camp was again ready for the most discriminating bwana hunter, and it was on to the serious business of determining he condition of its wildlife. Two close friends, Ron Bettendorf of Alabama and Jeff Whitehead of Mississippi, had joined me on my scouting mission, both in Africa for the first time. Their excitement was contagious to say the least!

Helping with the safari was Richard Brebner, a veteran Zimbabwe PH who had guided me on previous safaris in South Africa and Tanzania. Richard’s primary duties over the next 10 days would be to find a Cape buffalo for Scott and Cindy Davis of Georgia though he had already established several bait-stands for cats.

Helping with the safari was Richard Brebner, a veteran Zimbabwe PH who had guided me on previous safaris in South Africa and Tanzania. Richard’s primary duties over the next 10 days would be to find a Cape buffalo for Scott and Cindy Davis of Georgia though he had already established several bait-stands for cats.

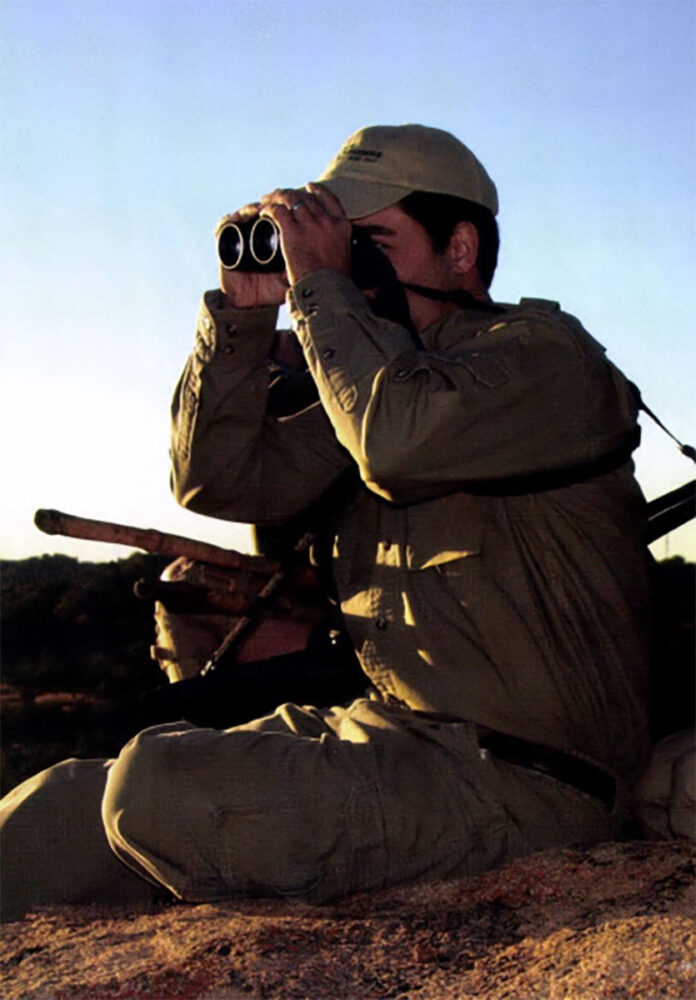

We spent the first morning riding part of the vast concession to check the leopard baits. It was obvious that the wild animals had not only survived but were thriving in spite of this dark time in Zimbabwe’s history. Jeff Whitehead’s beautiful, 56-inch kudu helped to confirm that the browsers were doing just fine. After checking all the baits, Rob and I decided to sit that night at one of the best leopard blinds on the property, a tall acacia tree at the edge of a meandering sand river.

As we crawled into our tent blind, I tried to get settled for what I knew could be a long wait. In fact, my “wait” had gone on for some 30 years. As a youngster growing up in rural East Tennessee, I had dreamed of hunting on the Dark Continent, and nothing captured my imagination quite like the leopard. One of the world’s most adaptable predators, the leopard can be one of the most dangerous animals on the planet.

I snapped to attention when the local wildlife population -rock hyrax, klipspringers and go-away birds – started their alarm calls, almost in perfect unison. I was prepared for a long wait, but only 20 minutes had passed. As I glanced down to grab my binoculars, I caught a movement out in front of the blind. There, directly in front of us — in broad daylight! — stood the biggest tom leopard I had ever seen in more than twenty safaris.

The dominant tom, confident in his position as king of this riverine forest, glided through the scattered rocks and boulders in the little clearing, then stopped. Rob and I remained completely still with the leopard only 75 yards away and looking intently at our blind. Besides, we were confident he would continue to the bait.

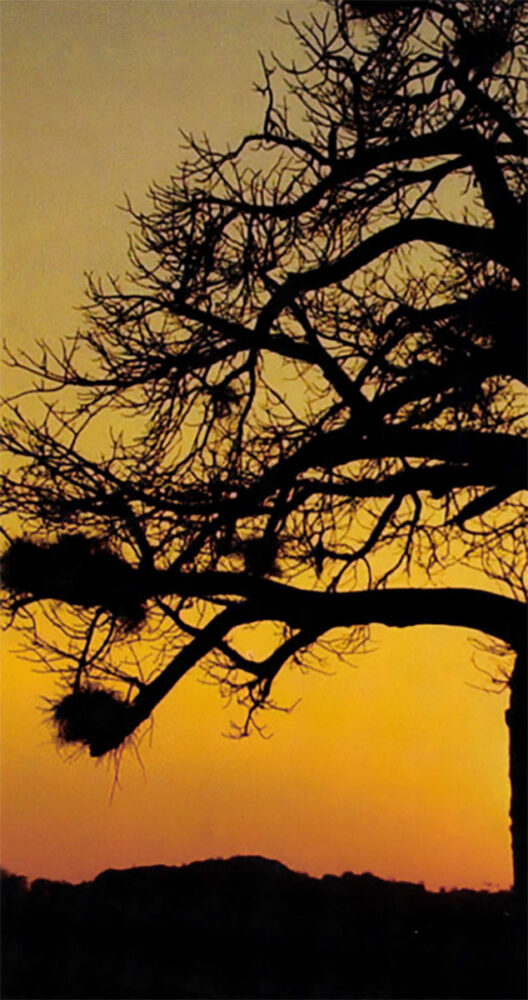

Instead, the big cat turned and moved down the riverbank, then vanished from Sight as the bright Zimbabwe day gave way to the graying dusk. As the light continued to fade, we expected to hear leopard claws scaling the bait tree at any moment. We sat on pins and needles for the next four hours waiting for his return, but to no avail.

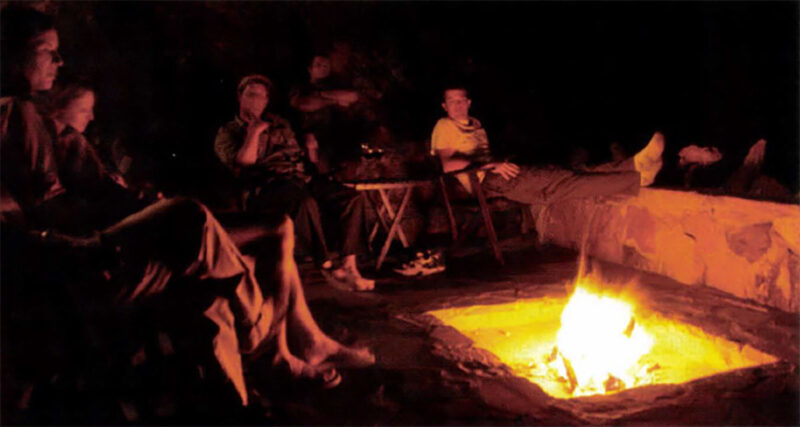

At breakfast the following morning the debate over last night’s hunt began. The “old school” crowd was convinced we should have allowed the cat to feed for a couple of days before sitting on the bait, while the younger crowd, eager to kill a leopard and with only eight days to hunt, felt we had made the light decision, even though the leopard had not returned. We deferred to wisdom and experience and decided to take the evening off from our leopard mission to join my buddies on a hyena hunt. After arriving at Hyena Hill, which has produced several of the top hyenas in the record-books, we sat back and enjoyed one of the spectacular sunsets that make Africa such a magical place.

Rob and I would only be observers this afternoon, so we simply sat back, and I enjoyed our share of cold Zambezi beers while waiting for the evening parade of wild animals. While heading to the ‘cool box’ for another beer; I crawled to the edge of the 80-foot cliff to check the hyena bait, only to find a tom leopard feeding on the carcass. He was a mature tom, though nowhere near the size of the monster we’d seen a few miles away, and after a quick discussion we decided to let him feed in peace.

After several minutes the leopard left the bait, a sure sign that hyenas were corning. Jeff and Scott soon had their hyenas trophies, and as we were driving back to camp, the thought hit me: two mature tom leopards in two days and nothing in the salt. I have been in the safari business long enough to know that many sportsmen leave Africa without ever seeing a leopard, and I had just let one walk that any hunter would be proud to take. Needless to say, sleep proved difficult that night.

The next morning dawned clear and much cooler. Anticipation was killing me as we headed to our bait tree to see if the big leopard had fed. While still a hundred yards away, it was obvious he’d returned, since the impala that we’d left the day before was completely devoured. There was only one thing to do: quickly go collect another impala and get it in the tree for the afternoon hunt. In certain areas of Africa that can be a mission, but with thousands of impala on Sentinel- a tribute to Digby’s tireless anti-poaching efforts — we had one in the tree by noon.

More focused than ever, Rob and I decided to sleep in the blind that night if that’s what it took to get our cat. I had an uneasy, anxious feeling as we drove to the bait tree just east of camp.

More focused than ever, Rob and I decided to sleep in the blind that night if that’s what it took to get our cat. I had an uneasy, anxious feeling as we drove to the bait tree just east of camp.

As the heat of the day slowly faded, I was gripped by an almost overwhelming feeling that this would be THE afternoon. Guineafowl flew to a nearby baobab trees to roost out of harm’s way. The sky turned to amber, then orange and finally a reddish glow that gradually dissolved into the approaching dusk. It’s moments like this that hold me captivated to this harsh continent and what draw me back again and again.

Just as the grey light was fading to black, I was shocked to attention by Rob’s hand in a death grip on my leg, our prearranged signal that the leopard has come.

Seconds passed like days and though I heard nothing, it was obvious that Rob had. As a bright full moon rose in the Southern Sky, I could make out the silhouette of the leopard — my leopard — ascending the tree. My heart started to race and I fought to stay calm.

In all my hunting experience, this was a feeling I had felt in the presence of only one other wild animal — a giant whitetail — but tonight the stakes were much higher. Rob calmed enough to release his grip, allowing me to move into shooting position. Through the riflescope I could see the cat standing like a statue just a few feet from the bait. As he edged toward his evening meal, Rob and I quickly determined that he was the huge cat we’d seen before.

Though 70 yards with a dead rest may seem like a chip shot, it is without question the most frequently missed shot on African dangerous game — and if you don’t kill the leopard, you’d better hope you missed! Just as I was taking the slack out of the Model 70’s trigger, the cat laid down on the limb to enjoy his newfound repast of fresh impala fillets. With Rob’s urging — some thing to the effect of “shoot the –––––– leopard now!” — I took careful aim and squeezed the trigger.

Though 70 yards with a dead rest may seem like a chip shot, it is without question the most frequently missed shot on African dangerous game — and if you don’t kill the leopard, you’d better hope you missed! Just as I was taking the slack out of the Model 70’s trigger, the cat laid down on the limb to enjoy his newfound repast of fresh impala fillets. With Rob’s urging — some thing to the effect of “shoot the –––––– leopard now!” — I took careful aim and squeezed the trigger.

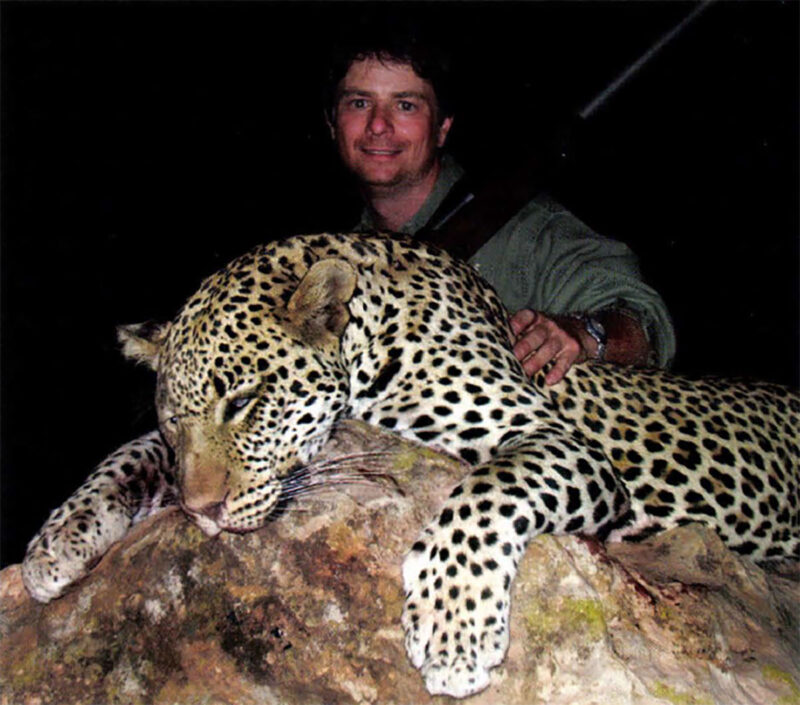

At the shot, the cat catapulted out of the tree, crashing through the branches and hitting the ground with a loud thud. The thud, according to many old-timers, is a sure sign that a leopard has been hit hard.

Rob stuck his head out through the blind just in time to hear the leopard crash away into the thorn bush while letting out a deafening roar.

We sat quietly for 20 minutes or so without saying a word, both thinking of the task at hand. It’s never fun to roust out a wounded leopard, and I had seen firsthand the damage they can do when one of our PHs had been mauled a few years before.

The trackers arrived shortly with Rob’s old 12-gaugeEnglish double in tow. I would carry his open-sighted 416, which posed a small problem because it has a light-handed action and I’m a southpaw. Not that it would matter, though, as in the dark you’re lucky to get one good shot before you’re wearing a not-so-happy leopard!

Our initial plan was to slip toward the tree and evaluate matters. What we saw when we got there made my heart jump in my throat. I could only imagine what Rob was thinking. Along with a few drops of blood, we found my 270 bullet inside the limb where the cat had been resting. With this in mind, we formed a second plan: we would walk shoulder to shoulder, a couple steps at a time, toward where we last heard the leopard.

Two steps into the thick cover, Rob heard something and immediately began backing up. After a short discussion with his tracker Philamon in the native Shona language, Rob informed me that the leopard sounded as if he was “very sick.”

At this point we formed a third plan, which we hoped would be the charm. We decided to cross the open, rocky area where we’d seen the cat on the first afternoon, expecting to find him in a small island of thorn bush on the other side of the sand river. We also expected to find him waiting for us, ready to exact the revenge that only a wounded leopard can.

At this point we formed a third plan, which we hoped would be the charm. We decided to cross the open, rocky area where we’d seen the cat on the first afternoon, expecting to find him in a small island of thorn bush on the other side of the sand river. We also expected to find him waiting for us, ready to exact the revenge that only a wounded leopard can.

As we inched forward, I swept my Surefire flashlight back and forth over the dense undergrowth. Suddenly, I caught a glimpse of the leopard’s glowing eyes. I traded the 416 for my scoped 270 WSM and handed the light to Philamon who trained it on the snarling animal. One shot at 60 yards ended our ordeal — or so we hoped.

After throwing several rocks into the thicket and without hearing a sound, we crept in to find the leopard stone dead. My first bullet had hit right on the shoulder, then passed through one lung — before striking the tree.