In a market increasingly dominated by loose, painterly works that imply rather than show, Daniel Smith is an unreconstructed realist.

Dan Smith

“Let me show you some real cool sheep,” Daniel Smith says. He rifles through a stack of slides, pushes one of them across the light table, then hands me the loupe. Sure enough, it is a shot of a half-dozen magnificent bighorns bathed in late-afternoon light, each turning into the sun, apparently unaware of the cameraman — Smith — who is taking their picture. Very cool sheep.

“I shot these in Jasper,” he says, beaming.

Smith combs his thick brush of gray hair straight back, and at fifty, still has the compact, muscular from of the amateur body builder he used to be. It seems at odds with the artsy outdoor type he also is, but then, most of his career has been at odds with the mainstream art world’s ideas of what wildlife art is and just as important, what sells. In a market increasingly dominated by loose, painterly works that imply rather than show, Smith is an unreconstructed realist. It is a mode of painting, he admits, that he assumed he’d transition out of.

“I always thought I’d have to change my style to be accepted,” he says. “But that’s not the way it evolved.”

Hippo eyeing the banks.

His house is full of prints, rather than originals, of his work (“I can’t afford my own stuff,” he cracks), and the detail is striking — a leopard resting on the burl of a dead tree, every hair in repose; a bull elephant materializing out of tendrils of mist. It’s superbly detailed work, and looks just as good at six inches as it does at six feet. It strikes me, as have works from other artists of Smith’s caliber, that this is nothing less than magic.

Smith claims he never did the starving-artist routine. We’re sitting in his kitchen sipping coffee, and an impressive kitchen it is. Timbers rise from floor to ceiling, and 20 feet away a massive stone fireplace soars two stories above the living room.

Smith attended college briefly, then transferred to art school. Shortly after completing his studies he found work in illustration, drawing for the corporate likes of Betty Crocker, decorating yogurt containers, and sketching album covers for, as he calls them, “B-class rock & roll bands.” Then he discovered duck stamp competitions.

Canyon Outpost

“I was a duck-stamp mercenary,” he says. Along the way, he won the Federal Duck Stamp contest in ’87, as well as four first-of-states and two first-of-nations. After 30-some duck stamps(as well as a pheasant stamp he painted in 1983), Smith found he didn’t have to do illustration work anymore. He’s been painting wildlife — with occasional forays into other subjects — ever since. He shakes his head. “I stated making a living immediately,” he says. “It was amazing.”

Smith doesn’t produce a lot of paintings — perhaps two dozen a year — but an ingrained blue-collar work ethic (two of his brothers are in the plumbing business) puts him in his studio at eight every morning, where he spends the day. “I’ve never been one for waiting for inspiration,” he says. Instead, he paints whether he feels like it or not, and finds that in doing so, the inspiration is there when he needs it.

It takes Smith anywhere from several days to a month to complete a painting, depending on its size and complexity, “and if I’m struggling with it,” he laughs. But Smith is rarely so involved in a painting that he won’t take time off to watch a the mule deer, whitetails and elk that roam through his backyard or the moose that occasionally take a dip in the recirculating pond below the cantilevered deck of his home. In fact, he says — emphatically —that it is wildlife and being outside that are by far his biggest motivations in painting.

Can a painting essentially comprised of one color still be convincing and interesting? Dan Smith’s Riverbank Procession trumpets a resounding yes!

“Most everything begins out in the field with actual hands-on seeing, smelling, feeling . . . “getting jazzed up and taking trips,” he says. “My painting is my reason to be doing all that. I’d rather be doing that any day instead of sitting up here and painting. The painting process . . . it’s fun and it’s creative, but the real enjoyment for me is being out there and experiencing it, seeing the colors, getting rained on and snowed on. That’s where it really comes from.

Smith grew up in Minnesota, and spent much of his childhood hunting and fishing. Today, his success and a sizable family keep him indoors painting far more than he’d like. He and his wife, Liz, have three children, all of whom are “at that age where the cash demand is huge,” he says. Consequently, he spends more time behind an easel than a camera, but he does take two or three weeks off every year to visit Africa, a place he’s fallen in love with.

His work traces the transition. Early pieces revolved around whitetail deer, wolves, cardinals and northwoods scenes; today, a Daniel Smith painting is as likely to be an African Cape buffalo, jaguar or lion. The walls of his home are cove red with African masks; a huge giclee of an African elephant looms above his fireplace. But it would be a mistake to assume he’s any less enthralled with American wildlife, particularly the predators that abound near his south west Montana home.

In Cape Crusaders, the artist has managed to capture the character unique to each animal, yet together the trio reflects the notoriously bad attitude of Cape buffalo bulls.

He gestures behind me with his coffee cup. “Bear broke in back there a while ago,” he says. “That room has our parrot in it, and I guess there were lots of yummy smells. So this bear got up on the window, and the parrot was freakin’ out. It was the middle of the night. The bear had a bad paw, so what I thought was: rogue bear. My son had just finished watching the Blair Witch Project, so he freaked out too and locked himself in his room. Anyway, I boarded up the window and the bear never came back.”

Dan Smith is surprisingly down-to-earth about how he paints, and he’s more than happy to tell me about his lists of “ingredients,” which he shares with students he sometimes teaches at his close friend and fellow Montanan Paco Young’s art classes. He crosses his studio — it’s well kept and quite small” and digs through a stack of wildlife studies: photos of elk, deer, bears, lions, cape buffalo, leopards, birds and ducks. Occasionally he’ll work directly from one photo, but more often he’ll file scenes from several different shots, juxtapose them in his head and then transfer the final product onto hardboard. He taps a photo of a horizontal log, one end of which is hidden in green foliage, then shows me another shot he took of a regal black jaguar. Married, the two became Apparition Of The Amazon, a painting of a jaguar resting on the very same log, the lower half of its body partially obscured behind leaves. It’s painted in dark, almost brooding acrylics, but there’s nothing sinister about it. In fact, that’s one of the striking things about Smith’s work: there’s nothing anthropomorphic in any of it. No cute timber wolves, no evil leopards, no majestic-looking elk. Just animals, the way they really are, in the habitat they really live in.

Yellowstone Procession

Paco Young agrees. “He is one of the guys who really does understand wildlife,” he tells me. “When we critique paintings or look at ideas we’re considering for paintings — we both seem to have a pretty good understanding of animals — but Dan really knows wildlife. He knows what the coat should be at that time of year, he knows bison look shaggy in the spring, because they should look shaggy in the spring.

“He also puts a good bit of animation in his pieces, as well,” Young continues. “You always get the feeling that it (Smith’s subjects) have just finished doing something or are just getting ready to do something else.”

Smith can’t remember when he wasn’t interested in art. He was, he says, always recognized as an artist, or at least, the artistic one in his family. Although he’s had financial success almost from the beginning, he’s had to learn how to deal with the business end of the art world, which has been considerably more difficult.

Dan Smith is wonderfully skilled at using nature’s elements to define his wild subjects. In Autumn Haze, the early morning mist serves to emphasize the reclusive nature of mule deer.

“Over the years, my driving force has changed,” he says. “Going way back to commercial art . . . obviously I had somebody dictating (what I had to draw), And then, in the duck stamp part of the business, you know, you had very specific criteria you were working within; tight parameters. Then my evolution into the print market seemed like it gave me much, much more freedom, but still I was painting stuff that I wanted to sell in mass quantities if I wanted to sell prints. And most of what I was doing I was doing with that in mind.

“But now, with the demise of the print market, my motivation comes more from within, what I want to do, what inspires me. Does the market dictate (what I paint) and how much attention I pay to it? I don’t know how you can not subliminally let that affect you, unless you live in a nutshell somehow. Yet so many people deny that that (the market) has any effect, but I look a little deeper than that.

Deep Forest Descent

“How can it not have an effect?” he muses, “Every art piece that you see, every painting, every image, it all goes into that image bank, that library in your mind, and it all comes out when you’re making decisions. So when I’m looking at my reference, trying to decide what would be a neat thing (to paint), I’m looking for attitudes; I’m looking for mood; I’m looking for things that convey what I experience and what I think. For instance, I’m just starting a new mountain lion painting this morning, and it’s a real neat kind of stalking posture, which to me [epitomizes] mountain lions: the neat musculature, the power, the stealth. I’m always looking for something like that, to kind of [encapsulates] the critters and bring out their best traits.”

Smith says that there are times when he is immersed in the spiritual side of painting, and claims that when everything is clicking, when the painting, as he says, “almost seems to paint itself,” he produces some of his finest work. But he also admits that spirituality per se is a hit or miss proposition. More often, he’d rather be outdoors in it than indoors painting it.

“It’s such a kick. I enjoy that so much,” he says of his time spent studying and photographing animals. ”I’m envious of these professional photographers, although, if I was out in the field the whole time, maybe it would become not as special as it is,” he says.

Canis Lupis

“It’s a real juggling act when you’re a professional artist. You’re juggling between the painting time, which is extremely important, the field work, which is, you know, kind of the chicken that lays the egg and then the promotional aspects, going and doing the shows, signing your name and doing all the business end of it. And so you’re always juggling those three facets of the business. Keeping a balance has always been a challenge, and I think I do it well — but it’s hard to juggle those three balls.”

Back in his studio, Smith has a nearly completed painting of a herd of buffalo on his easel. He’s painting from a photo he took on Ted Turner’s Flying D ranch, a 45 minute drive from his home. He shows me the photo, which is a pastoral shot of two dozen bison grazing in an open pasture, the Spanish Peaks looming behind them.

At first glance, his painting looks identical. But there’s something different, something warmer, about the tone. When Smith points out that he’s moved the focus from the left side of the painting to the right, I begin to see it. A subtle refocusing of the light, which now rests on a lone bull grazing apart from the herd. Then each animal comes to life. Somehow, they look more real than in the physical reality of the photograph, more alive. And I’m struck once again — this is magic.

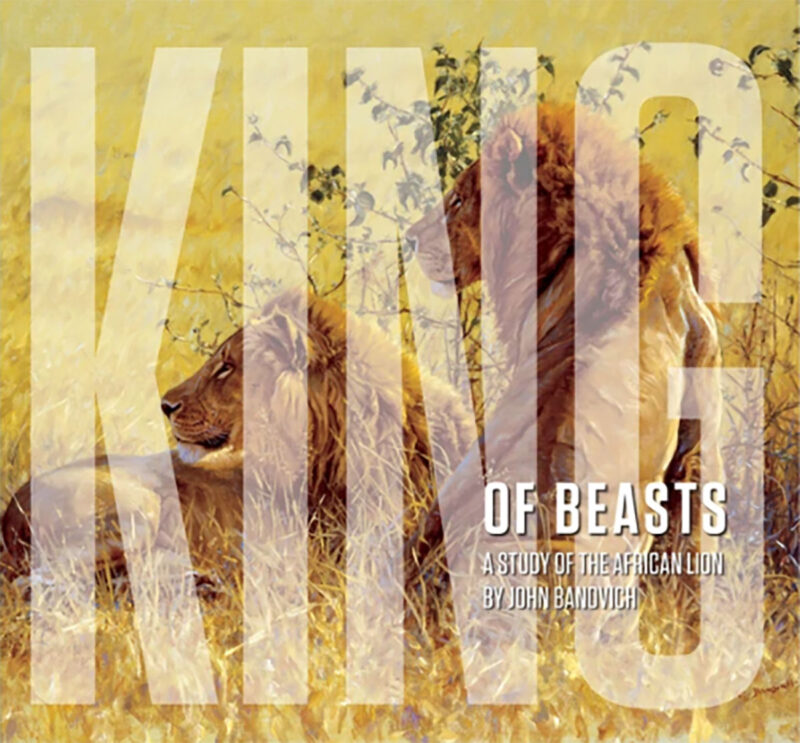

John Banovich believes he was born to tell the lion’s story — from its ancient past to its troubling future. And on these pages, he tells that story the best way he knows how — by painting it.

John Banovich believes he was born to tell the lion’s story — from its ancient past to its troubling future. And on these pages, he tells that story the best way he knows how — by painting it.

Over his illustrious 26-year career as an award winning artist and one of the world’s foremost contemporary naturalists, John has continued to draw and paint the African lion more than any other subject, simply because no other animal speaks to him quite the same way. “Have you ever felt something so deep and visceral that you know in your heart without question that it is a world you want to be in—a relationship you want? Kind of like falling in love is the best way I can describe it. That’s how the lion made me feel.” Buy Now