Damascus-barreled shotguns are considered inferior to those made with fluid-steel barrels, but are they really more dangerous to shoot?

Damascus, the capital of the Syrian Arab Republic, is a big city surrounded by an even bigger desert. Nearly two million inhabitants call Damascus their home. The old city is surrounded by a wall and the River Barada. These days the river is most always dry, particularly because the annual rainfall is a scant five inches. My friend didn’t think about the ancient city when I pulled the Damascus-barreled shotgun from its case in the vibrant October foliage. Could shotguns like this one really be safe to shoot?

“Where’d you grab that blunderbuss?” he laughed. “From someone’s fireplace?”

“It’s a buddy’s,” I said. “I’m thinking about buying it.”

“Well, I’ve got my cell phone. Hopefully I’ll get a signal to call 9-1-1 when it blows up.”

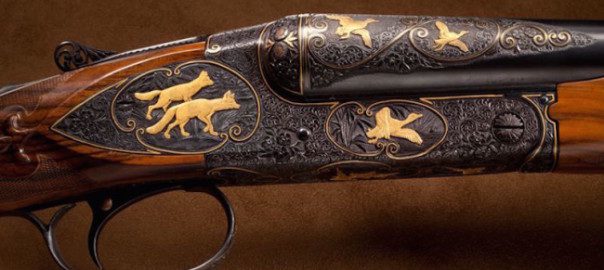

A pair of 12-bore heavy actions with half carved four seasons engraving by Bradley Tallett.

He joked about the Old Blunderbuss while my setter, Rebel, cast through the alder hell down by the river. He added more insults as we quickly walked around the orange and red-leafed maples in the pass-through cover. His jokes stopped in the aspen run when Rebel locked up on point. His head was high and his tail set at a measurable 90 degrees when a grouse rumbled out from under his nose. I dropped the bird with one shot, the blunderbuss remained intact and the shotgun’s efficacy came up in no further conversations.

These days, Damascus-barreled shotguns invoke fear and avoidance from both shooters and hunters. These antique firearms are considered inferior to those made with fluid-steel barrels. Damascus, a general term describing the combination of steel and iron, was first used for edged weapons as early as the third century. As swords and knives were sold in volume in Damascus, the unique metal carried the name.

Perfection over the next millennium resulted in early Damascus firearm barrels being made in Eastern and Near-eastern countries. Trade brought them to Europe in the mid-1790s. A Frenchman, Jean- Francois Clouet of Liege, was among the first Western gunmakers to experiment with Damascus barrels.

Several years later, two Englishmen, William Dupein and J. Jones, expanded on that process with Jones patenting a new process of turning a bevel-edged band of metal into a spiral-twist with interlocking threads. To make these barrels, iron and steel plates were stacked one on top of each other, heated and hammered to create one block of mixed metal. That block was then heated and drawn to form a rod.

The process was repeated until six such rods were made, and then the rods were prepared for heating and twisting. Three of the rods were twisted with a right-facing thread while the other three were twisted in the opposite direction with a left-facing thread.

Thin ribbons were wound around a mandrel, heated and hammer-welded to create barrels.

A thin metal sleeve was wrapped around a mandrel over which the barrel ribbons were wound. The threads were connected, heated and hammer-welded, the mandrel was removed and a barrel was formed. It normally took seven feet of rod to create one foot of barrel.

The process that many of us know is the Crolle Damascus pattern-welded barrels. Some are artistic and contain highly figured patterns based on how the two different-colored metals were “piled” or layered while the rods were twisted. When twisted, the outer layers move inward. The various degrees of depth that come from the number of threads per inch determines the pattern, with some being simple chevrons or diamonds while others being more complex. The layering of metal combined with the twists are how names can be written into steel.

British gunmakers manufactured Damascus steel barrels through the early 1930s. Americans, eager to switch to smokeless powders that burn more slowly and maintain high pressures for higher velocities and longer-distance shots, preferred barrels that would accommodate that extra pressure.

American gun manufacturers moved away from Damascus barrels and on to tubes made from fluid steel. Around the 1880s, Damascus barrels became an object of the past.

Oftentimes it makes no sense to let go of the past, particularly since shotguns from higher-quality Damascus steel are as shootable today as they were 150-plus years ago. Firearms manufactured by lesser-known companies are what give Damascus guns a bad rap. Smaller companies used lower-quality metals and sub-par construction that, when combined with modern ammunition, causes some barrels to burst. Still, and in many circles, Damascus guns offer shooters the opportunity to acquire high-grade, vintage shotguns for more than a reasonable fee.

Lars Jacob, owner of Lars Jacob Wingshooting, has been a tremendous proponent of shooting Damascus-barreled shotguns for decades. He’s so bullish on them that he usually has several in his Dorset, VT, gun room.

“Damascus-barreled shotguns in good repair are highly functional,” Jacob said. “Barrel integrity is the most important— and the least understood—element of shooting vintage Damascus-barreled shotguns. Before you buy a Damascus-barreled shotgun, have a reputable gunsmith inspect your firearm.

“I find that barrels fail inspection from one of three distinct issues,” he said. “The first comes from pitted bores, which are often caused by a manufacturer’s use of soft iron or poor welding techniques.

“Pitting also can come from improper storage over time. If the bores have been reamed to remove rust and pits, then the wall thickness is altered. When excessive amounts of metal are removed, then the barrel integrity is compromised and is therefore weakened. Gunsmiths use micrometers to measure barrel thickness in a variety of places and then compare those measurements with factory specs.

“A second reason Damascus guns fail inspection is because the barrels have been dented while hunting. It’s easy to remove dings from fluid steel barrels, but their removal from twist barrels creates a soft spot and lessens barrel integrity.

The Viking Gun, 12 bore with Damascus barrels. Carved by Alan Brown.

“A third issue resulting in failed inspections relates to chokes. Most vintage guns had tighter chokes. Improved cylinder and modified were common, and modified and full were as well. If your candidate has cylinder and skeet chokes, then the odds are high that the chokes have been opened at some point. Each of these conditions is easily assessed by a competent gunsmith with a micrometer.”

Shooting low-compression shells is a must. Thanks to companies such as RST and Polywad, these traditional shells are commercially available.

“Chambers in the 1800s were the standard of the day, 2 1/2 or 2 5⁄8 inches,” Jacob noted. “While a modern 2 3/4-inch shell will fit into the chamber, they pose problems upon discharge. Modern shells feature full crimps and, when fired, the crimp extends beyond the chamber’s length. Damage to forcing cones and hinge pins along with increased compression are a by-product.

“All that is necessary is to shoot short, low-compression shells from companies like RST Shotshells and Polywad, among others.”

Shawn Wayment is a bird hunting veterinarian from Colorado who specializes in treating bird dogs. He isn’t afraid to reach into his gun cabinet and extract a Damascus-barreled shotgun.

“I’ve got seven Damascus guns,” he said. “Two are Parkers, two are Lefevers and three are Frank Hollenbeck drillings. Every one of their barrel patterns is unique, and they’re all gorgeous.

“My first Damascus gun was a Parker GH 16 gauge on an O frame,” said Wayment. “Because it’s a 16 gauge on a 20-gauge frame, it’s light and is considered to be the Holy Grail of grouse guns. I found it at M.W. Reynolds shooting and fly fishing store in Denver, and when I mounted the gun, it fit perfectly.

“After a thorough inspection, I bought it on the spot. I’m a bit more careful when hunting with the Damascus gun, and because I hunt at high elevation in rugged terrain, I’m cautious not to ding the barrels. I shoot RST 2 1/2-inch low compression shells, and I’ve killed one heck-of-a-lot of birds. These days I don’t care if a shotgun’s barrels are fluid steel, Damascus or twist. If the gun fits, I buy it.”

Are brand new shotguns with Damascus barrels available? Graham N. Greener, director of W.W. Greener Sporting Guns LTD, has been making shotguns with Damascus barrels for some years.

“Our company was the last English gunmaking company to make Damascus barrels and production of these ceased in 1903,” he said. “However, we had a stock of these and so we decided to make shotguns with these barrels again and some with steel and Damascus interchangeable barrels. These have mostly been sidelock side-by-side sporting shotguns in 12 and 20 bore. All have been made to individual orders, including pairs and sets of guns. Many are featured on our website.”

There is a reason that Damascus barrels are no longer in current production, and that’s because the quality of available materials is metallurgically harder than before. Still, one gunsmith, Missouri’s Steve Culver, gave it a try.

“Laffite’s Revenge” is Steve Culver’s award-winning combination weapon. He fashioned both the blade and barrel from Damascus steel. PHOTOGRAPH BY STEVE CULVER

As both a master knifemaker and a master gunsmith, Culver sought to create a firearm that combines his two unique skill sets.

“I made ‘Laffite’s Revenge’ as a combination weapon,” he said. “I designed the flintlock mechanism to create a .50-caliber flintlock pistol with a spiral-welded Damascus barrel. To that I added a 12-inch long Damascus blade that features a Woodhead pattern.

“You’ll note that the spine slopes downward toward the point; that slope enables the blade to be out of the shooter’s view when aiming,” he explained.

“I made three combination weapons from Damascus, and that will be all. They’ve been a highlight in my career, but the required production time as well as the required materials are too much. Still, I don’t know of any modern gunsmith who has made Damascus barrels. Do you?”

I do not, but what remains is that while shooting a Damascus-barreled shotgun requires more due diligence from a quality gunsmith and the shooting of low-compression shells, these firearms are safe to shoot. And if properly cared for, I suspect they’ll continue to drop grouse and quail a hundred years from now.