“You don’t decide on a style…you do the work and a style evolves.”

Over the years, I have had the luck to interview some very talented wildlife artists. A number actually hunted, others did not. In the work of those that did, I discovered another quality, a sincerity perhaps.

Clearly one of the best hunters among artists, Cole Johnson’s work is astonishing. I recently accompanied him on a spring turkey hunt, stumbling behind in the predawn darkness as he glided silently over a hayfield. He arranged the decoys and we set up at a forest edge, watching the stars go dim. At first light came the long, scolding grind of a roosted bird behind us. Shortly after, a coyote walked out and Cole looked at me collusively, knowing it would spook the bird but reveling its lurking, sinister trot. From such encounters in the wild, Cole obtains his genuineness. What less experienced wildlife artists believe to be a natural pose is often way off. Clearly, Cole’s knowledge of animals goes beyond mere perception to insight.

Clearly one of the best hunters among artists, Cole Johnson’s work is astonishing. I recently accompanied him on a spring turkey hunt, stumbling behind in the predawn darkness as he glided silently over a hayfield. He arranged the decoys and we set up at a forest edge, watching the stars go dim. At first light came the long, scolding grind of a roosted bird behind us. Shortly after, a coyote walked out and Cole looked at me collusively, knowing it would spook the bird but reveling its lurking, sinister trot. From such encounters in the wild, Cole obtains his genuineness. What less experienced wildlife artists believe to be a natural pose is often way off. Clearly, Cole’s knowledge of animals goes beyond mere perception to insight.

The coyote left abruptly, probably winding us, and the old tom resumed his shrill admonishment. Cole killed him later, when the gobbler flew down to the decoys, spreading his wings and parading his colors in the newgrass before us. That sight was plenty for me, but Cole was already at work, studying the turkey as he would recreate him in black and white and gray.

Sportsmen’s scrutiny of art stems from their comparison to the real thing. We assume Vermeer accurately depicted 17th century Delft, but there is only the paintings of other Dutch masters to judge him by. When it comes to wildlife art, one has only to walk outside. Nature is rich in subject matter, but use of artistic license must be reasonable, abstract spare. There is little for the wildlife artist to hide behind. The art of Cole Johnson is both original and real. Although he trained formally in oils, he works exclusively in pencil. That he is also a hunter, fisherman and consummate outdoorsman weighs heavily in his work.

Sportsmen’s scrutiny of art stems from their comparison to the real thing. We assume Vermeer accurately depicted 17th century Delft, but there is only the paintings of other Dutch masters to judge him by. When it comes to wildlife art, one has only to walk outside. Nature is rich in subject matter, but use of artistic license must be reasonable, abstract spare. There is little for the wildlife artist to hide behind. The art of Cole Johnson is both original and real. Although he trained formally in oils, he works exclusively in pencil. That he is also a hunter, fisherman and consummate outdoorsman weighs heavily in his work.

The art that results is like no one else’s — delicate renderings of North American game, fish and birds that blend intimacy with intricacy.

“You don’t decide on a style,” declares the young artist. “You do the work and a style evolves.”

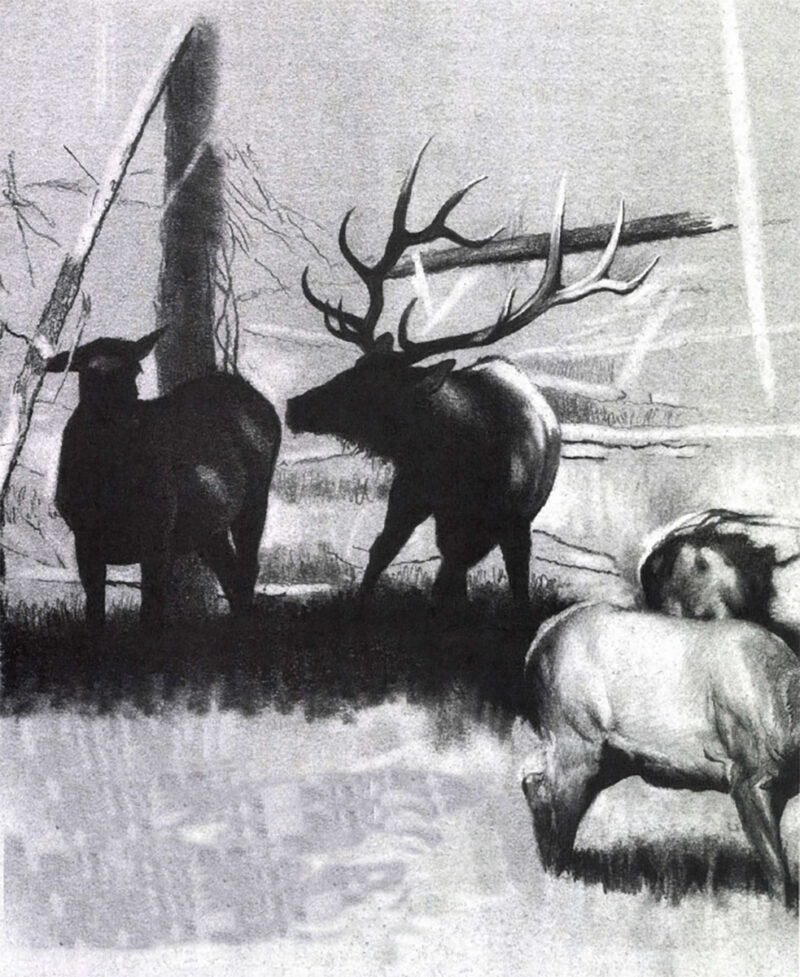

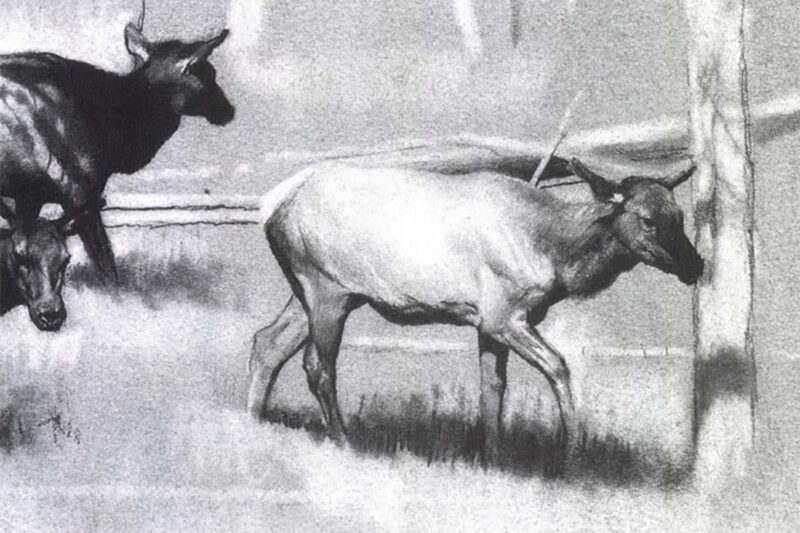

Cole’s drawings begin with a pencil, but it’s his later use of powdered graphite that provides the surrounding hues and tonal softness, subtlety and a foggy notion of what lies beyond — tall prairie grass, a forest, a hedgerow. On the subjects, however, the composition is tight and the margins clear. His loose, painterly backgrounds create a negative space so that the piece is unquestionably about the subject.

Cole’s drawings begin with a pencil, but it’s his later use of powdered graphite that provides the surrounding hues and tonal softness, subtlety and a foggy notion of what lies beyond — tall prairie grass, a forest, a hedgerow. On the subjects, however, the composition is tight and the margins clear. His loose, painterly backgrounds create a negative space so that the piece is unquestionably about the subject.

Says Cole: “Part of it is working the setting, not just applying it. I have to lay down this medium ground, then reintroduce light by taking away. Initially, it’s a fairly loose application. Later, it becomes tighter and more detailed. “When a piece is almost completed, I stop working and display it where it can be viewed from a distance. There isa risk of becoming overexposed to a composition and not being able to pick up inconsistencies. This cooling off period enables me to be a little more objective.”

So much of Cole’s work is impressive that it is difficult to decide what to profile. New to his work, I liked everything and focused on several that truly expressed his method. One piece that immediately caught my eye was a dramatic portrait of an osprey, its fierce gaze riveted on something beyond the borders of the drawing. The bird’s black and white plumage is highly detailed, yet the drawing is wonderfully artistic in the way it created a strong, emotional response within me. Another drawing, Fallen King, was of a freshly dead kingbird that Cole’s mother retrieved seconds after its early morning collision with a fence. Knowing that its principally black and white colors would lend itself to his style, she rushed it inside to his studio. Cole immediately began to draw the bird on its back.

So much of Cole’s work is impressive that it is difficult to decide what to profile. New to his work, I liked everything and focused on several that truly expressed his method. One piece that immediately caught my eye was a dramatic portrait of an osprey, its fierce gaze riveted on something beyond the borders of the drawing. The bird’s black and white plumage is highly detailed, yet the drawing is wonderfully artistic in the way it created a strong, emotional response within me. Another drawing, Fallen King, was of a freshly dead kingbird that Cole’s mother retrieved seconds after its early morning collision with a fence. Knowing that its principally black and white colors would lend itself to his style, she rushed it inside to his studio. Cole immediately began to draw the bird on its back.

“Something is lost within several minutes of a bird’s death,” he explains. “No matter what technique the artist uses, it will never look the same. I raced to capture it, knowing that the suppleness would soon be gone.” The piece is wonderfully stark and one views it reflectively, as though watching the last few moments of life pass from the subject. All Cole Johnson’s drawings are studies.

Since childhood, Cole’s subjects have been provided by the wildlife around his family farm north of Binghamton, New York. At age seven, he etched his first renderings in the fungus that grew on tree stumps. Fueled by his outdoor ramblings, Cole continued to sketch profusely but quietly. In high school, though not enrolled in any of the art classes, a teacher convinced him to submit some drawings to a student art exhibition. “I did small pencil sketches of a mockingbird and a wood duck,” Cole recalls. “The response from everyone was very positive which surprised me because I wasn’t that involved in art back then. That experience convinced me to pursue art on a higher level.”

Since childhood, Cole’s subjects have been provided by the wildlife around his family farm north of Binghamton, New York. At age seven, he etched his first renderings in the fungus that grew on tree stumps. Fueled by his outdoor ramblings, Cole continued to sketch profusely but quietly. In high school, though not enrolled in any of the art classes, a teacher convinced him to submit some drawings to a student art exhibition. “I did small pencil sketches of a mockingbird and a wood duck,” Cole recalls. “The response from everyone was very positive which surprised me because I wasn’t that involved in art back then. That experience convinced me to pursue art on a higher level.”

Cole went on to enroll in the fine art program of Munson, Williams, Proctor Institute of Art in Utica. He then attended Buffalo State, graduating in 1991 with a degree in fine art. Every artist struggles economically. Commercial employment existed at that time, but Cole was turned off by industrial art. Choosing to remain true to his motif, he took a construction job and squeezed drawing into his 50-hour work weeks. Those were tough times. However, his work has gained the success it deserves, thus opening new subject opportunities. Western game is appearing in more of Cole’s drawings.

Among Cole’s many awards are the Eastern Region of The National Arts for the Parks Competition and Best of Show in the Yankee Heritage Wildlife Art Expo, Art in the Animal Kingdom III and Somerset County Carving and Wildlife Show. In 1998 Cole was inducted into the prestigious Society of Animal Artists and two years later won their coveted Award of Excellence. I spent a day with Cole at his family farm near Green, New York. His studio is an unpretentious, sunlit section off the main house. On a commissioned work, he demonstrated his use of graphite shading. Initially moderate near the edge of the canvas, the mood heightens as it reaches inward to its subject, the expressive and vital face of a border collie. Cole’s Elhew pointers, on the other hand, are reserved and distinctly elegant.

Among Cole’s many awards are the Eastern Region of The National Arts for the Parks Competition and Best of Show in the Yankee Heritage Wildlife Art Expo, Art in the Animal Kingdom III and Somerset County Carving and Wildlife Show. In 1998 Cole was inducted into the prestigious Society of Animal Artists and two years later won their coveted Award of Excellence. I spent a day with Cole at his family farm near Green, New York. His studio is an unpretentious, sunlit section off the main house. On a commissioned work, he demonstrated his use of graphite shading. Initially moderate near the edge of the canvas, the mood heightens as it reaches inward to its subject, the expressive and vital face of a border collie. Cole’s Elhew pointers, on the other hand, are reserved and distinctly elegant.

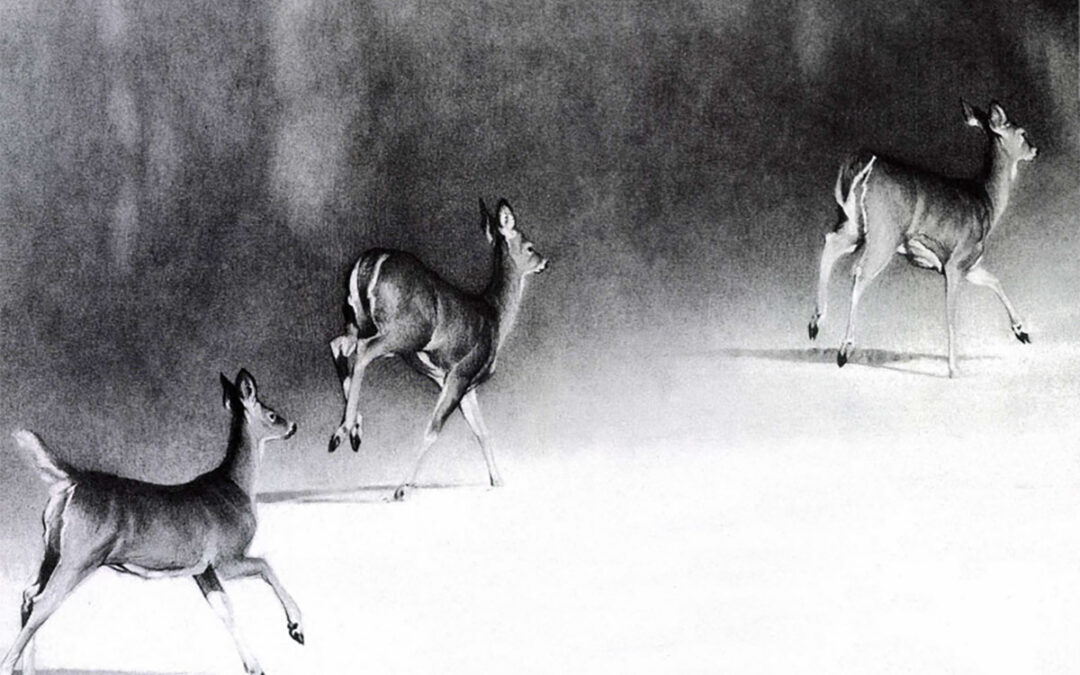

What Cole is able to evoke every time is the prevailing disposition of each subject. A larger, more ambitious piece depicts a small herd of bucks and does bounding along the edge of what we perceive as dense woods, which the artist loosely delineated in a soft blending of gray shadows. The deer themselves are varying shades of gray and black that somehow define sinew, joint, ligament — flexion and extension, the articulation of movement.

“Anatomy is very important to me, but more so is how that anatomy moves,” Cole says. “The sprightly gait of an antelope versus the swaying, lumbering motion of a moose. With mammals I want to depict the illusion of mass and weight. With birds you have a sense of lightness and the effortless ability to ascend. What I attempt to do is to avoid an illustration — what a deer or bird simply looks like — but to create life.”

In some of his drawings, bringing an animal to life is mostly a matter of drawing shadow. In Cole’s White on White, an enchanting portrait of a willow ptarmigan, what defines the bird’s form are those parts of its body in shadow against the white snowscape. “The contrast of that shadow and the light of the paper create the image,” Cole explains. “Together, they create the illusion of the bird’s mass.” Beautifully conceived and stunning in its simplicity, the drawing won a best of show at an Art & The Animal exhibit in Vermont and was selected for a special tour of original works organized by the Birds in Art exhibition at Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wisconsin.

In some of his drawings, bringing an animal to life is mostly a matter of drawing shadow. In Cole’s White on White, an enchanting portrait of a willow ptarmigan, what defines the bird’s form are those parts of its body in shadow against the white snowscape. “The contrast of that shadow and the light of the paper create the image,” Cole explains. “Together, they create the illusion of the bird’s mass.” Beautifully conceived and stunning in its simplicity, the drawing won a best of show at an Art & The Animal exhibit in Vermont and was selected for a special tour of original works organized by the Birds in Art exhibition at Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wisconsin.

Insight, study, rendition, the hidden mystery we call the artist’s eye. When I left Cole, he was seated in his studio, regarding a large tail-feather from the turkey he had taken only hours before. Pondering how the bird would live again on canvas, he turned the feather over in his hands as the day’s light filled the room. I crept away as quietly as I could, fortunate to have so exceptional a talent among today’s sporting ranks and the promise of enjoying his unique style for many years to come.

The authors have spent nearly forty years assembling this rare collection of all fifty-five of Frank Benson’s etchings in the hunting and fishing genre. The strength and subtlety of the pieces show off Benson’s mastery of technique and artistry. For subject matter for the etchings he chose his pastime passions, hunting and fishing. The book fully documents the etchings, how they were created, their focus/subjects, background and provenance, including their sale at auction. In the world of art, it is generally held that Benson will be best remembered for his etched work. Buy Now

The authors have spent nearly forty years assembling this rare collection of all fifty-five of Frank Benson’s etchings in the hunting and fishing genre. The strength and subtlety of the pieces show off Benson’s mastery of technique and artistry. For subject matter for the etchings he chose his pastime passions, hunting and fishing. The book fully documents the etchings, how they were created, their focus/subjects, background and provenance, including their sale at auction. In the world of art, it is generally held that Benson will be best remembered for his etched work. Buy Now