One Christmas I was to be at the ranch, and I made up my mind that I would try to get a good buck for our Christmas dinner; for I had not had much time to hunt that fall, and Christmas was almost upon us before we started to lay in our stock of winter meat.

So I arranged with one of the cowboys to make an all-day’s hunt through some rugged hills on the other side of the river, where we knew there were whitetail.

So I arranged with one of the cowboys to make an all-day’s hunt through some rugged hills on the other side of the river, where we knew there were whitetail.

We were up soon after three o’clock, when it was yet as dark as at midnight. We had a long day’s work before us, and so we ate a substantial breakfast, then put on our fur caps, coats, and mittens and walked out into the cold night. The air was still, but it was biting weather, and we pulled our caps down over our ears as we walked towards the rough, low stable where the two hunting ponies had been put overnight. In a few minutes we were jogging along on our journey.

There was a powder of snow over the ground, and this and the brilliant starlight enabled us to see our way without difficulty. The river was frozen hard, and the hoofs of the horses rang on the ice as they crossed. For a while we followed the wagon road, and then struck off onto a cattle trail that led up into a long coulée. After a while this faded out, and we began to work our way along the divide—not without caution, for in the broken countries it is hard to take a horse during darkness.

Indeed, we found we had left a little too early, for there was hardly a glimmer of dawn when we reached our proposed hunting grounds. We left the horses in a sheltered nook where there was an abundance of grass and strode off on foot, numb after the ride.

The dawn brightened rapidly, and there was almost light enough for shooting when we reached a spur overlooking a large basin around whose edge there were several wooded coulées. Here we sat down to wait and watch.

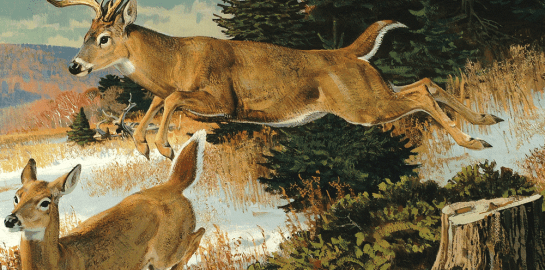

We did not have to wait long, for just as the sun was coming up on our right hand we caught a glimpse of the little ravines some hundreds of yards distant. Another glance showed us that it was a deer feeding, while another behind it was walking leisurely in our direction.

There was no time to be lost, so, sliding back over the crest, we trotted off around a spur until we were in line with the quarry and then walked rapidly towards them. Our only fear was lest they should move into some position where they would see us; and this fear was justified.

While still 100 yards from the mouth of the coulée in which we had seen the feeding deer, the second one, which all the time had been walking slowly in our direction, came out on a ridge crest to one side of our course. It saw us at once and halted short; it was only a spike buck, but there was no time to lose, for we needed meat, and in another moment it would have gone off, giving the alarm to its companion. So I dropped on one knee and fired just as it turned.

From the jump it gave I was sure it was hit, but it disappeared over the hill, and at the same time the big buck, its companion, dashed out of the coulée in front, across the basin. It was broadside to me and not more than 100 yards distant; but a running deer is difficult to hit, and though I took two shots, both missed, and it disappeared behind another spur.

This looked pretty bad, and I felt rather blue as I climbed up to look at the trail of the spike. I was cheered to find blood, and as there was a good deal of snow here and there, it was easy to follow it; nor was it long before we saw the buck moving forward slowly, evidently very sick.

We did not disturb him, but watched him until he turned down into a short ravine a quarter of a mile off. He did not come out, and we sat down and waited nearly an hour to give him time to get stiff.

When we reached the valley, one went down each side so as to be sure to get him when he jumped up. Our caution was needless, however, for we failed to start him. On hunting through some of the patches of brush, we found him stretched out already dead.

This was satisfactory; but still it was not the big buck, and we started out again after dressing and hanging up the deer. For many hours we saw nothing, and we had swung around within a couple miles of the horses before we sat down behind a screen of stunted cedars for a last look.

After attentively scanning every patch of brush in sight, we were about to go on when the attention of both of us was caught at the same moment by seeing a buck deliberately get up, turn round, and then lie down again in a grove of small, leafless trees lying opposite to us on a hillside with a southern exposure. He had evidently very nearly finished his day’s rest but was not quite ready to go out to feed, and his restlessness cost him his life.

As we now knew just where he was, the work was easy. We marked a place on the hilltop a little above and to one side of him. While the cowboy remained to watch him, I drew back and walked leisurely round to where I could get a shot.

When nearly up to the crest I crawled into view of the patch of brush, rested my elbows on the ground, and gently tapped two stones together. The buck rose nimbly to his feet and, at 70 yards, afforded me a standing shot, which I could not fail to turn to good account.

A winter day is short, and twilight had come before we had packed both bucks on the horses. With our game behind our saddles we did not feel either fatigue, or hunger, or cold while the horses trotted steadily homeward. The moon was a few days old, and it gave its light until we reached the top of the bluffs by the river and saw across the frozen stream the gleam from the fire-lit windows of the ranch house.

A winter day is short, and twilight had come before we had packed both bucks on the horses. With our game behind our saddles we did not feel either fatigue, or hunger, or cold while the horses trotted steadily homeward. The moon was a few days old, and it gave its light until we reached the top of the bluffs by the river and saw across the frozen stream the gleam from the fire-lit windows of the ranch house.

In this groundbreaking epic biography, Douglas Brinkley draws on never-before-published materials to examine the life and achievements of our “naturalist president.” By setting aside more than 230 million acres of wild America for posterity between 1901 and 1909, Theodore Roosevelt made conservation a universal endeavor. This crusade for the American wilderness was perhaps the greatest U.S. presidential initiative between the Civil War and World War I. Roosevelt’s most important legacies led to the creation of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and passage of the Antiquities Act in 1906. His executive orders saved such treasures as Devils Tower, the Grand Canyon, and the Petrified Forest. Buy Now

In this groundbreaking epic biography, Douglas Brinkley draws on never-before-published materials to examine the life and achievements of our “naturalist president.” By setting aside more than 230 million acres of wild America for posterity between 1901 and 1909, Theodore Roosevelt made conservation a universal endeavor. This crusade for the American wilderness was perhaps the greatest U.S. presidential initiative between the Civil War and World War I. Roosevelt’s most important legacies led to the creation of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and passage of the Antiquities Act in 1906. His executive orders saved such treasures as Devils Tower, the Grand Canyon, and the Petrified Forest. Buy Now