Need help deciding on the best choke tube for your shotgun? Here is your guide to different choke types and choosing which is right for you.

Searching for the best choke tube? Which is it? Traditional, wad-retarding, ported, un-ported, the one your buddy uses? The history of choke is full of twists and turns all culminating in the later years of the 20th century with screw-in choke tubes.

The history of the shotgun goes far back, but its development really began when Joseph Manton (April 6, 1766 – June 29, 1835) fashioned two flintlock guns together giving the double shotgun its lines that have lasted until today. Christopher Spencer and Sylvester Roper developed the first successful pump-action shotgun in 1882. Its toggle action was unique and clunky, but what made it stand out was the set of three rings that screwed onto the muzzle that were the first interchangeable chokes! Winchester’s John Browning-designed Models 1893 and 1897 pumps quickly eclipsed the Spencer, and Browning’s Automatic 5 completed the styles of shotguns we enjoy today.

Illinois River market hunter and trap shot Fred Kimble who claimed he invented choke but didn’t. That prize goes to Sylvester Roper.

The History of the Choke Tube

In 1881, the British gunmaker W. W. Greener wrote an immense tome, The Gun and Its Development, in which he took credit for inventing the choke. By the ninth edition, he placed the invention where it belonged, with Sylvester Roper. Greener wrote, “The invention of choke-boring has been claimed by many, [but] is usually attributed to American gunsmiths. The first patent for choke-boring was granted to Roper, an American gunsmith, on July 14, 1868, thus preceding the English claimant, [William Rochester] Pape’s by about six weeks.”

In 1881, the British gunmaker W. W. Greener wrote an immense tome, The Gun and Its Development, in which he took credit for inventing the choke. By the ninth edition, he placed the invention where it belonged, with Sylvester Roper. Greener wrote, “The invention of choke-boring has been claimed by many, [but] is usually attributed to American gunsmiths. The first patent for choke-boring was granted to Roper, an American gunsmith, on July 14, 1868, thus preceding the English claimant, [William Rochester] Pape’s by about six weeks.”

Greener mentions choke boring as early as 1781 when M. de Marolles said, “An iron and wooden mandrel, fitting the bore, is furnished at one end with small files, which cut transversely only. This tool put into the muzzle of a barrel and turned round by means of a cross handle, forms a number of superficial scratches in the metal, by which the defect of scattering the shot is remedied.”

Not to be outdone, the Illinois market hunter and trap shot Fred Kimble boasted of inventing choke boring. He hunted the duck-rich Illinois River with a 6-bore muzzleloading Joseph Tonks of Boston shotgun that he claimed was the first choke-bored gun, but Roper wins the prize. Roper was quite the inventor and is also credited with perhaps inventing the first motorcycle. He died while demonstrating a bicycle with an added steam engine that clocked a speed of 2 minutes 1.4 seconds per mile. During one of the laps, he became “unsteady” and dropped dead of heart failure.

The Purpose of Choke

The purpose of choke is simple: It shapes the pattern. The lead shot used until the advent of nontoxic steel and others was soft and it deformed in several ways: at ignition (called “setback”) from the force of the burning propellant ramming it forward, barrel scrubbing or from rubbing on itself, all leading to long strings of shot and erratic patterns at the target. Choke in its many forms is aimed at corrected these ills.

The Poly Choke showing the steel fingers and the collet that compresses them.

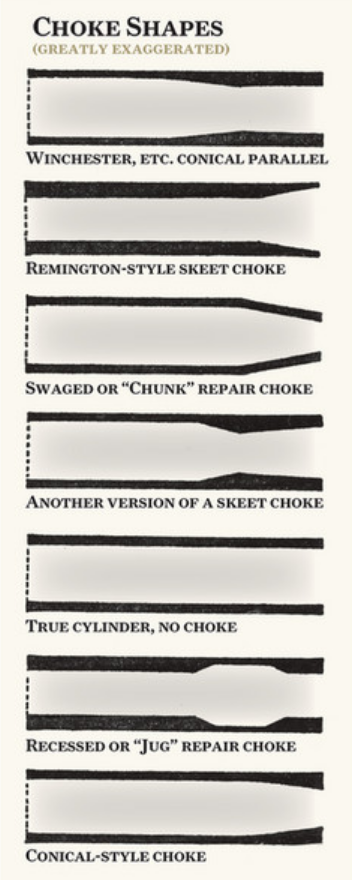

The Conical-Parallel Choke

Until the Winchester Model 59 semi-auto came along in 1959, all chokes were bored at the factory with two exceptions I’ll get to in a minute. Several styles were used depending on the manufacturer. Perhaps the best was Winchester’s that used the conical-parallel formula that tapers from the cylinder bore to the desired constriction, then maintains that dimension out through the muzzle. The theory is that the constriction is established and then the shot charge is steadied until it exits the muzzle. Remington used a similar system with its skeet chokes, only flaring them a bit between the parallel and the muzzle. Other shotguns such as the famed and finest bespoke London-best shotguns also use this style of choking.

The Pure Conical

Another system is the pure conical that was often used on lesser-priced shotguns. Here the barrels were all bored full choke at the muzzle then a reamer is introduced from the breech end and simply run in as far as the indicated choke, i.e., farther for improved cylinder and not at all for full choke.

Another system is the pure conical that was often used on lesser-priced shotguns. Here the barrels were all bored full choke at the muzzle then a reamer is introduced from the breech end and simply run in as far as the indicated choke, i.e., farther for improved cylinder and not at all for full choke.

The Chunk Choke

There are also two “rescue” chokes for barrels that were damaged by trying to “shoot out” an obstruction like snow, mud, etc. One was called by a Wisconsin gunsmith a “Chunk Choke.” It was a very heavy block of steel with a tapered hole in the center. In use he would secure the barrel in a vice then drop his Chunk Choke onto the muzzle. He repeated it until some degree of constriction was re-established.

The Jug Choke

Perhaps less rustic was the recessed or “jug” choke, wherein the barrel was chucked into a lathe then a recess was cut an inch or so before the muzzle that allowed the shot charge to expand then be constricted by the smaller muzzle.

The Poly Choke

The first “adjustable” choke was the Poly Choke that came along in the 1920s. Boasting “Nine Degrees of Choke,” it is a conical-style choke that uses a set of six steel fingers that are compressed or loosened by means of a tapered collet that compresses or relaxes the fingers. Marketed by outfits such as Herter’s Inc. in Waseca, MN, under its own name as the “World’s Finest,” the Poly Choke is still available to fit popular screw-in choke-fitted guns. In my experience, Poly Chokes did pretty well with open patterns, less so with tighter settings.

The Cutts Compensator

In competition with the Poly Choke was the Cutts Compensator. Invented by Marine Corps Colonel Richard M. Cutts to attenuate the severe muzzle climb of the Thompson submachine gun, it was easily transferred to shotguns in all gauges. A cage-like device was installed using an adaptor that threaded onto the barrel’s muzzle. Some skeet guns made by Remington and Winchester were designed for use with a “Cutts” and had their muzzles forged and threaded. Into the end of this cage were threaded choke tubes of varying constrictions.

One unique use of the Cutts Compensator was with Remington’ recoil-operated Model 11-48 .410 skeet guns. Because of the light recoil of the .410 shell, often the 11-48 would not reliably cycle with 2 1/2-inch shells, so the Cutts was made to direct the propellant gases forward, thus increasing the recoil to push the barrel back and cycle the gun. An early form of porting, the Cutts’ cage directed the propellant gases up helping attenuate recoil and, as with the Thompson, barrel rise. One of the best choke tubes for sporting clays and popular among skeet shooters, the Cutts increased the report noise so much that they were forbidden by the Amateur Trapshooting Association.

The Development of the Screw-In Choke

In 1959 the choke scene changed dramatically with the introduction of the Winchester Model 59 semi-auto. Based on Winchester’s Model 50 semi-auto as a lightweight hunting gun, they both used the “Carbine” Williams-style sliding chamber of the M1 Carbine. With its aluminum receiver and barrel made with a thin steel tube around which was wound fiberglass topped with a set of three screw-in choke tubes, the butt-heavy gun was not popular as it has the swing characteristics of a fly swatter, but it heralded the development of the screw-in choke.

Winchester Model 59 semi-auto

It wasn’t long before Seattle, WA, gunsmith, the late Stan Baker, figured out a way to expand the muzzles of shotguns and install his screw-in tubes. The late Jess Briley hopped on the bandwagon with his thin-walled choke tubes that could be used in any shotgun because it was not necessary to expand the muzzle as with Baker’s. My first association with Jess was in 1985 when I bought two AyAs in their gun vault in Eibar, Spain. The 28-gauge No. 2 was bored modified and full, however the importer’s gunsmith flubbed the attempt to open the chokes, so I called Mr. Jess. Still my favorite dove gun, the tubes are invisible save for their two-notches just at the muzzle.

Many a shotgun has been saved by screw-in chokes. I once bought a Browning Double Automatic, the two-shot short-recoil gun of the 1950s that came with an optional aluminum receiver anodized in black, red, blue, green, purple or silver. Some jackleg “gunsmith,” which the late Jack O’Connor called a “lawnmower sharpener,” had opened up the full-choke barrel; except he made the choke elliptical to the naked eye—off to Briley for a rescue set of thin-wall chokes!

Briley Thin-Wall choke tubes in an AyA No. 2 28-gauge barrel. They can be used to salvage an off-center or damaged choke, too open choke or make a shotgun truly versatile for any game or cover.

Types of Screw-In Chokes

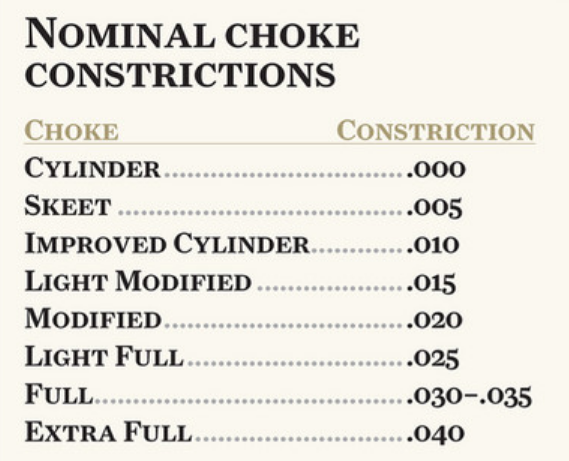

Screw-in chokes come in different styles; parallel-conical, conical and wad-retarding being the principal types plus ported and non-ported. Chokes are subtle things. An extra-full 12-gauge constriction is .040-inch─about the thickness of a couple business cards─and today’s super-full turkey tubes run .060-inch. What is most important is the relationship between the choke’s constriction and the cylinder bore of the gun. In the 1920s the Olins─Franklin, John and Spencer─who owned the Western Cartridge Company in Alton, IL, developed the Super X shotshell that promised superior performance over the other then-available shells. Using a progressive-burning propellant and copper-plated pellets, they were a big step in the right direction.

Ported Patternmaster choke tube showing the internal ring of “studs” that retard the wad, The ports help cut muzzle rise.

Concurrent with the Super X, Boise, ID, lawyer E. M. Sweeley and gun guru Colonel Charles Askins spent a summer refining shotgun barrel performance. The result was the A. H. Fox HE-Grade Super Fox that used a tapered chamber that gentled the shot into the .740-inch over-bored cylinder bore via a long tapering forcing cone. The bore ended with a 6-inch taper to a tight .040-inch choke constriction. All proving that optimum downrange shotgun performance relies upon the relationship between the load, the forcing cone, the cylinder bore and the choke.

Some choke tube manufacturers use the conical-parallel tradition and are pretty much a duplication of the traditional bored chokes of yesteryear. The tubes that come with shotguns are normally of pure conical design.

For a number of years, going back to the 1960s, there has been a move by some choke people to pull the wad back away from the pattern. One choke guru of the 1960s cut a spiral groove into the choke area to spin off the card and felt wads of the period. More recently there have been chokes made to clear our contemporary plastic wads. Perhaps the best known is the Patternmaster that uses a circle of studs to strip the wad from the shot. The theory is that there is little need for constriction if you get the wad out of the way. With hard, non-deforming steel shot, tight patterning is far less of a problem than with lead shot. An earlier choke devised by Winchester ballistics guru Ed Lowery used a set of concentric circles that retarded the wad and gave excellent patterns.

Porting of barrels and choke tubes goes directly back to the Cutts Compensator that provides some recoil attenuation and perhaps more importantly, it reduces muzzle rise caused by recoil. Faster follow-up shots at both clays and game result from the gun staying along the flight path of the bird.

How to Measure Your Choke Tube

Measuring chokes is not really essential to the hunter and shooter, but for those interested you can purchase digital barrel micrometers for about $100 for a 12-gauge and about $500 for a four-gauge ─12, 20, 28 and .410─set. There is also a universal set, the Boremaster Multi-Gauge, that uses a digital caliper system. There are even plug-style choke measuring devices that give a relative dimension and are useful when checking guns at gun shows and elsewhere.

Choke is not a gross measurement. Here is .040-inch, extra-full, on a dial caliper, about the thickness of a couple of business cards.

Using a barrel micrometer to measure choke constriction as it relates to a specific barrel is done by zeroing the micrometer in the cylinder barrel then measure the choke tube at its tightest point and the result is the constriction for that barrel/choke combination. You can also use the old method of comparing a 12-gauge muzzle to a U.S. dime, which will tell you that without a doubt you have a shotgun and a dime, and nothing else.

Three choke measuring devices, a digital micrometer, Robert Louis Company’s caliper style and a plug style that will provide a rough measurement of a choke in all gauges.

Choosing the Best Choke Tube for Your Shotgun

Selecting a choke tube for your shotgun that provides the performance you want really entails some work on your part. You need to shoot patterns, evaluate them, then draw your conclusion based on those facts, not advertising or what “Uncle Zeb” uses.

All choke data is based on the industry standard of 40 yards that was established somewhere in antiquity. However, in 1957 George G. Oberfell and Charles E. Thompson published their findings from extensive research in a book called The Mysteries of Shotgun Patterns that contains the basis of shotgun patterning and such nuggets as, “[The] Effect of Roughening of [the] Inner Surface of Choke Tubes,” the results of which show an increase of about five-percent with “roughened” tubes. Oberfell and Thompson were using the ammunition of the day, which included Remington, Western, Federal and Sears’ brand J. C. Higgins that was loaded by Federal. Most still used card and felt wads and most had adopted the folded or “pie” final crimp, although some probably used the rolled crimp with a card top wad. Regardless, their finding still rings true today. Here’s how you should test your load/barrel/choke combination.

How to Test Your Load/Barrel/Choke Combination

First determine which ammo you plan to use as they can all provide slightly different performance in your gun. Find a safe space with a good backstop, then measure 40 yards using a rangefinder or surveyor’s tape. You can buy targets at your local gun shop or get some butcher paper that is 40-inches square (you can tape smaller-size paper such as old Christmas wrapping together). Shooting from a solid rest, fire three to 10 patterns aimed at the center of each target. My late friend Don Zutz suggested three patterns if they seemed similar, if not then go to five with 10 being more definitive. Once you have your shot targets in hand inscribe a 30-inch circle around the greatest concentration of pellets, count them and divide by the number of pellets in the shell. You can dissect a shell─I use a pharmacist’s pill counter─or refer to one of the tables on the internet, and you then have a working percentage. You need to repeat this routine for every choke and shell you plan to use. Yes, it takes time, but in the long run you’ll have supreme confidence in your gun/choke/shell combination.

Obviously, choke is a complicated affair, made all the more so with the proliferation of screw-in chokes. Taking the time to see how they respond to your choice of shells, what game you are hunting and at what range will go a long way to unveiling the mysteries of choke.

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case.

In Fine Shotguns, expert John M. Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, France, Spain and Italy. Here are all types of shotguns: single barrel, double barrel, combination guns, hammer shotguns, paired shotguns, special-use guns, small-bore shotguns, shotgun stocks or shotguns with metal finishes and bespoke shotguns. This all encompassing guide includes sections on how to care for and storage your weapon, what accessories are available for your model, and how to choose the perfect traveling case.

John M. Taylor began hunting with his father at age five. He has written for major outdoor publications, including Petersen’s Hunting, Gun Dog, The American Rifleman, Outdoor Life and others. He is currently the shotgunning editor of Sports Afield, Delta Waterfowl and Pheasants Forever magazines. He lives in Lorton, Virginia. Shop Now