“He wondered if the dog would recognize him, hoping in one breath that he wouldn’t and in the next knowing it would be the cruelest blow he ever suffered.”

The captain led Ben into a small study. “Ben,” he said, I’m looking for a good young dog. A real field trial dog. A dog that has a chance to win the national. That dog of yours, that Derry, might be what I’m looking for. I’ve a hunch he is.”

Ben looked at the captain, then away. He felt real fear now, cold and hard, and wished desperately that he hadn’t come. He drew a breath that hurt his chest and said, “Yes, sir.”

“Now, I don’t want you to think of how you got your dog at all. Don’t think you owe me any favors. You don’t and that’s a fact. He’s your dog, just as much as if you’d come to my kennel and paid a big price for him. But I’m going to make you a proposition. I’m going to offer you five hundred dollars for that dog. And on top of it, the choice of any other pup I’ve got. You’re perfectly free to take it or leave it.”

Five hundred dollars meant riches such as Ben had never known. It meant lifting the ceiling of fear that pressed his family down. But Derry. He could not let himself think of Derry. It seemed now as if it had been predestined from the beginning. If he had only been wiser he could have seen it coming, sure and certain as the procession of the days. He could, of course, refuse. For a moment he clutched at the thought as if it were a sturdy floating plank and he a boy drowning. But no matter what, you always knew what you had to do. There was something that made you do it out of respect for your own self.

He said, “Yes, sir, captain.”

“It’s a deal,” the captain said. He opened a desk drawer, found a checkbook and wrote a check. He handed it to Ben. “Now we’ll go out to the kennel and you can have your pick again. And boy, I’ll bet you pick right.”

Ben stood up. He said quietly, “Thank you, sir, but I don’t want another dog, I’ll be going now.”

“Then you’re entitled to a hundred more.”

He didn’t answer that. He turned and hurried away. He heard the captain’s voice with a worried note to it, “Well, then I’ll send it down to you.”

Outside he did not look at Derry. He told him roughly to stay where he was and did not look back as the captain led him away.

At home he put the check on the table and told his father what had happened. His father picked up the check and examined it, holding it as delicately as if it were some fragile bit of china. Then he laid it down.

Ben said, “It’s yours. To do with what you want.” His father shook his head. He looked past the boy, above his head, as if there were something of great interest on the wall opposite. “Thanks for your favors. I don’t want no pa

rt of them. I got along and I always will. Maybe you’ll want to be buying a car with it, like your rich friends have.”

Ben stared at his father for a long time. His father’s eyes never lowered. A sudden gust of wind came through the open window and blew the check to the floor. His father picked it up and put it in the drawer of the table.

“It’ll stay there, for all of me and your mother,” he said. “You’ll know where it is when you want it.”

The days went by leadenly. At first it seemed that not having Derry was more than he could bear. Then one day he tore down the enclosure he had made and chopped the kennel into kindling. After that it was not so hard; it was as if with ax and hammer he had destroyed something that never should have been, and so, in a strange sense, set himself free from a harsh bondage.

Half a dozen times he met the captain. Always he escaped as soon as he decently could, not asking about Derry. The captain mentioned the dog once. That was soon after the sale, and the captain asked if he’d like to come up for a hunt. He made some palpably false excuse, and the captain, nodding his head, said gently, “As you like, Ben. I know. But he’s doing what he was made to do and that’s what any being should.” The captain did not speak to him of Derry again.

Half a dozen times he met the captain. Always he escaped as soon as he decently could, not asking about Derry. The captain mentioned the dog once. That was soon after the sale, and the captain asked if he’d like to come up for a hunt. He made some palpably false excuse, and the captain, nodding his head, said gently, “As you like, Ben. I know. But he’s doing what he was made to do and that’s what any being should.” The captain did not speak to him of Derry again.

He worked a day for a neighbor and earned enough cash to subscribe to a magazine devoted to field trials; the check still lay in the table drawer, untouched, and with it the check for an additional hundred which the captain had sent down by a servant. He read the magazine with infinite care, line by line, analyzing the dogs pictured, and finding none that had the grace and power and perfection that was Derry.

The first time he saw Derry’s name, the print seemed to leap from the page. It was in an early article covering a tricounty trial, and it simply said that Derrydale Captain, owned by Capt. Richard Harmon and handled by Joe Bleecher, had placed second. Derry, the article went on, “ranged nicely and obviously had an excellent nose, but was not too well controlled.”

He felt anger at the criticism, then wonder that Derry had come in but second. Yet Bleecher was a famous trainer and handler, to whom the captain had sent many of his most promising dogs. It was ridiculous to think that the outcome would have been different had he been the handler that day, but that night he slept badly and dreamed of hunting with Derry, and the dog was the great champion of all the great champions of the world.

Derry’s name appeared frequently after that – a third here, another second there, a first in one or two county trials where the competition was entirely unworthy of him. In the Western, he did not place at all. Once there was a picture, a small, one-column cut taken at a bad angle. He stood for a few minutes looking at it, miserable with the pictorial injustice of it.

He kept the magazines from his father’s sight. He was always first at the mailbox around the period when they were due to arrive. Once his father caught him as he was reading one in the barn. His father’s shadow fell across the page, and he looked up.

His father’s eyes were wide and bright. “So, our gentleman is improving his mind,” his father said. “It must be fine to be born to the purple.”

Ben stood up, holding the words back that wanted to gush out. He rolled the magazine and stuffed it in a pocket. ”I’m doing my work,” he said.

His father smiled. “When you getting that car? The money’s still in the drawer.”

“It’ll be there forever, far as I’m concerned.”

“And me too. I guess the captain’s ahead a nice piece of change. Well, if you can spare a minute I can use you. If you can lower yourself to help.”

The State Field Trial was coming up and he read in his magazine that the captain had three dogs entered. Derry was one. He was hoeing the kitchen garden a day or two later when the captain’s car came down the road stopped near him.

They shook hands gravely and the captain stuffed tobacco into his pipe. “Ben, Derry’s not going like I hoped. I don’t know whether you know.”

“I know. I’ve been reading about it.”

“I figured for him maybe a national champion one day. And he couldn’t win even those little trials. It’s hard to blame Bleecher. He’s got a record back of him.”

Ben put the hoe down. “Bleecher ought to know as much as anybody.”

“There’s such a thing as a dog working right for only one man.” The captain said. “It doesn’t happen often, but it does happen.” He saw what was coming and wanted desperately to dodge it. He never wanted to see Derry again. That was one thing of which he was dead sure. And all he could do was stand cow-like before the captain and wait for him to say what he knew he was going to say.

The captain put his pipe in his jacket pocket. “I want you to handle Derry in the State. I’ll pay you the same as I would Bleecher.”

Ben broke in angrily, “I wouldn’t take pay for a thing like that.”

The captain eyed him curiously. “Well, we can argue that later. It’s a detail. The point is – will you do it?”

He looked away from the captain, seeking hastily for excuses. There was but one he could hit on that was at all valid. “We’re busy now. I got to help. You know how it is in this season.”

“I know,” the captain said. “I can send a man down to take your place.”

“And my father – well, he wouldn’t like it. He doesn’t think much of things like dog trials. For me, that is. And I can guess I’d better—”

“I can fix that with your father.” There was a way the captain said that, as if he thought his father nothing more than the servants that waited on table, or milk cows in the fine pastures. Ben stiffened and looked away stonily, his whole being an intense discomfort.

The captain watched him for a moment, then said, a different tone to his voice, I’d think he’d be mighty proud of you handling a dog – maybe a winning dog – in that trail. After all, it’s second only to the national. Yes, I’ve a feeling you’ll be out there with Derry.”

He could find nothing to say. The captain left him then, striding away to his car, and Ben watched him drive off. When he looked to the barn, he thought suddenly, his heart beating painfully hard, that he could see the wire enclosure and the doghouse within. He had to run his hand across his eyes to banish the strange illusion.

The captain came for him early and they drove off into the cold, clear morning. His father had said good-bye to him calmly, without comment, as if he were going off on some ordinary errand.

The captain drove fast, humming a tune, keeping his short brier pipe going like a furnace. Ben sat huddled in his ancient overcoat, his body a bundle of active nerves.

The trial was held at one of the great farms, 20 miles away, and long before they reached it the traffic grew thick. There were little cars and big cars, old cars and new, and the men who drove them were the big, smiling kind of men whose lives were given largely to their interest in sporting dogs.

They arrived and the captain got out, stretched, and pointed to a dog trailer hitched to a big coupe parked under a clump of trees. “That’s Bleecher’s rig,” he said without emphasis. “Derry’s there.”

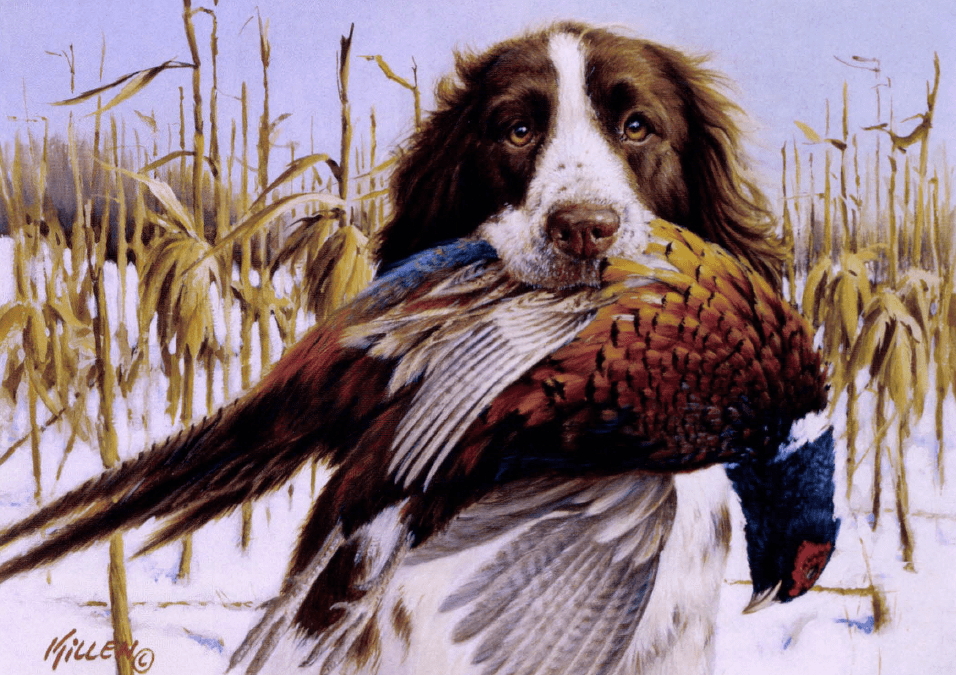

Ben walked to the trailer slowly, wondering if the dog would recognize him, hoping in one breath that he wouldn’t and in the next knowing that it would be the cruelest blow he had ever suffered. Then Bleecher’s boy, at the captain’s nod, was opening the trailer back and Ben was saying, “Hello there, Derry,” and the dog was hurling himself upon him. The dog barked twice, a high-pitched, staccato sound, and his eyes were blazing with eagerness.

Ben said, “Charge, Derry,” and the dog hesitated, then dropped. He could resist no longer. He knelt and ran his hands lovingly down the smooth flanks, his head close to the dog’s ears so he could talk to him without being overheard.

Afterward he took him away into an empty field and gave him orders. He had him cross and quarter the ground and threw a rubber ball for him to retrieve. He was still busy with this when the captain appeared. “You’re going out in twenty minutes,” the captain said. “How’s he doing?”

“He’s fine.” Ben said. “He can win this.”

“He’s got tough competition. It’s the best lot the state ever saw, to my mind. There’s a bitch here – shipped west by plane with her handler. She’s been taking everything.”

“He can win,” Ben said again. The feel of the captain ‘s hand on his shoulder was warm and pleasantly intimate, and he was glad the captain said nothing more.

Afterward, he tried to remember the day in full detail, and he failed. He remembered the beginning of it, when his own clothes seemed horribly shabby beside the fine boots and breeches and jackets of the big handlers. Then he put this firmly out of his mind and concentrated on Derry. He never looked at another dog, and he never allowed himself to think that another dog might be going better. When he came to the trailer in the early afternoon the captain spoke to him for the first time since the start.

“Well done,” the captain said. He really saw the Eastern bitch for the first time when it was announced that she and Derry were to go out together – the judges had not been able to decide between them for first honors. She was a liver-and-white dog, delicately but beautifully made, with the fine eyes and full muzzle of a great line. He saw her handler looking at him, smiling curiously; he drew his shoulders back and made a little speech of resolution to himself. Then the guns were ready, and the judges were down the field in a little knot.

They were to have three birds each, and before Derry found his first a shot to the left meant the bitch had scored. Then Derry found two in quick order and they were brought down and perfectly retrieved. The bitch found her second a moment later. Both found their third birds almost together – the shots came hardly a second apart.

It was over. As Ben walked back, Derry at heel, the sweat was dripping down his back and chest, though the day was not warm. The captain had his arm and was saying, “I don’t care which wins, I’ll never forget this. You even had Bleecher amazed. By the way, your father’s over there. He arrived a couple of hours ago.”

Ben turned quickly, and saw his father standing alone, dressed in his ancient Sunday best, the dust thick on his heavy, carefully polished shoes. There was about him an immense pride, as if it were his protection against a world full of humiliating and inimical things. He stood very straight and he looked like a man who was alone because it was the way he wished to be, not because he had no one to whom to turn for companionship.

Ben walked quickly toward him, thinking of how his father must have come because he could not bring himself to ask for a ride with Ben and the captain. The five-mile walk to town, the search for a lift to reach the farm…Ben felt a strange, soft emotion that was entirely new to him. He said, “Hello.”

His father said, “Hello. I guess you did all right out there.”

Now he could almost feel the pride – as if it were a stone wall between them. He said, “Listen – I want to tell you – I want to tell you I’m mighty glad you came. That makes it a good day…sort of caps it off, as they say.”

It seemed to Ben that a little of the ramrod stiffness went out of his father’s posture. “You mean that, Ben? You mean that, like you said it?”

“Of course I mean it.” His father smiled then, a wide, free smile that was reflected in his eyes. “I’m glad I came too. I guess there’s a lot more to these dog things than I knew.”

The loud-speaker rumbled then, and a metallic voice roared out, “The judges wish it announced that this was one of the closest and most brilliant contests in their experience. The winners are: first, Derrydale Captain, owned by Captain Richard Harmon and handled today by Ben Frazier. Second—”

He heard no more, for there was a pounding as of surf in his ears and his father and the captain were slapping him on the back and shouting. His mind was a spinning wheel of many colors that he thought would never stop.

It seemed a long time later that the captain was saying, “I’ve something to tell you. I’ll make it short. It takes you to handle Derry. He’s your dog. I’m giving him back to you, no strings attached. He won’t work right for Bleecher or me or anyone else. I’m doing this because I want to, Ben.”

The world was a calm and silent place now and he looked up at the captain, knowing at once what his answer had to be – as if it had been all prepared by some portion of his mind that had the gift of anticipation. “I can’t do that, sir.”

The captain didn’t answer but waited. “Because of Derry. He…he’s got to do what he’s supposed to do. Win the national. He can do it. It wouldn’t be right not to give him the chance to do that.”

“You mean,” the captain said slowly, “there’s a sort of absolute justice involved?”

“I guess that’s it. I can help Mr. Bleecher so Derry will work for him. Derry’ll do what I want. And I want him to be champion.”

“I see.” The captain looked away and when be looked back his eyes were soft and moist as a spaniel’s. “Only the way you feel about Derry, I thought—”

“It’s something I’ve got to work up to. To earn, I guess you’d say. And I will. I don’t care how long it takes, I’m going to work and save for it.”

The captain looked at him for a long time, then ran a big hand across his face. “Well. Well. Anyway, you go to your father. We’re having a victory dinner tonight at the house. And I’m going to see to it your mother comes up too.”

He found his father and they went along to the car. His father walked slowly, his head down. Ben took hold of his arm.

“I had an idea,” he said. “About you and me and what to do with the money the captain paid for Derry. Maybe we could use it to start a little place of our own. We could work it on the side, to begin with. I could help with all the work and then maybe get a pup cheap from the captain and start raising dogs and – well, I thought something like that might be all right.”

His father’s shoulders bent forward a little and he did not lift his head. “That was no thought of mine,” he said slowly. Then the words came out with a sudden burst, as if a dam had broken. “You could use that money for schooling. You’d ought to have more than just eighth grade. You could go to high school in town – the money would buy clothes and books and I could make out here without you maybe, if I worked Sundays and a little extra evenings. I never wanted – I never wanted you should grow up ignorant like me.”

Ben stopped short and faced his father with blazing eyes.

“What a thing to say!”

For the first time in his life he felt grown up, felt that he and his father were men together. “No man’s ignorant that can farm the way you can. No man’s ignorant that can train dogs right. But any man that don’t know what he can do and has to go to high school to try and find out – that’s awful ignorant!”

He stopped talking, suddenly conscious of his father’s eyes. They were looking straight into his own with a warm, awakening understanding. “All right,” his father said.

They walked on toward the car, keeping step, heads up, feet coming firmly and rhythmically down on the ground.

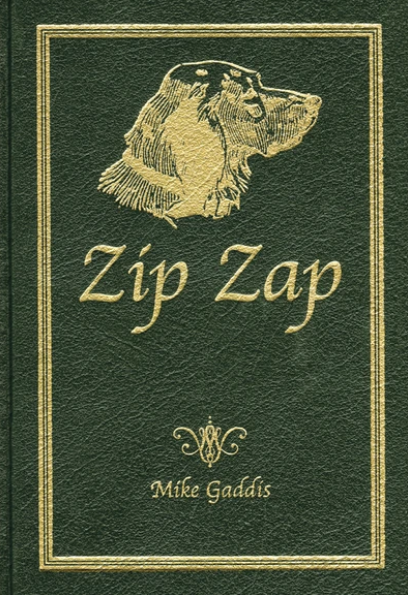

Zip Zap is a wonderful true-life story of a superb English setter and its litter-mates. On the heels of his highly-acclaimed novel Jenny Willow, Mike Gaddis reaches again into a half-century love affair with pointing dogs and upland birds to retrieve the true-life story of Zip Zap, his greatest English setter. Gaddis swore to be painfully selective in choosing the puppy that would accompany him as he pursued his dream of competing in horseback field trials. He knew the smallest female of the litter was special, but he didn’t fully realize her potential until he let her loose in the field. Her lightning speed earned her the name Zip Zap, and she grew to be the most brilliant bird dog Gaddis ever owned. In this absorbing memoir, Gaddis celebrates the dog’s indomitable spirit and tells the story of training and developing a superior pointer, from her first unrefined runs in the amateur puppy stakes to victorious performances in major championships. Evocatively told and set against the plantation quail hunting and field trailing legacy of the Old South, here is a rich, powerful memoir, certain to gain favor with anyone who has shared the destiny of a once-in-a-lifetime dog. Buy Now

Zip Zap is a wonderful true-life story of a superb English setter and its litter-mates. On the heels of his highly-acclaimed novel Jenny Willow, Mike Gaddis reaches again into a half-century love affair with pointing dogs and upland birds to retrieve the true-life story of Zip Zap, his greatest English setter. Gaddis swore to be painfully selective in choosing the puppy that would accompany him as he pursued his dream of competing in horseback field trials. He knew the smallest female of the litter was special, but he didn’t fully realize her potential until he let her loose in the field. Her lightning speed earned her the name Zip Zap, and she grew to be the most brilliant bird dog Gaddis ever owned. In this absorbing memoir, Gaddis celebrates the dog’s indomitable spirit and tells the story of training and developing a superior pointer, from her first unrefined runs in the amateur puppy stakes to victorious performances in major championships. Evocatively told and set against the plantation quail hunting and field trailing legacy of the Old South, here is a rich, powerful memoir, certain to gain favor with anyone who has shared the destiny of a once-in-a-lifetime dog. Buy Now