Jay “Ding” Darling, two-time Pulitzer-Prize-winning cartoonist and father of the Federal Duck Stamp program, was a friend of my grandparents, and he gave my young parents a Chesapeake Bay retriever pup as a wedding present. The newlyweds named the gift after the man, and Ding passed into family lore, the hero—or frequently anti-hero—of most of my father’s tales about the many dogs he had loved throughout his life. That most of these tales about Ding were tinged with wry humor, my father being the usual butt of the joke, should have warned me, but instead, I relished those stories of a time before me, and of a wildly colorful dog that towered above the constraints of time and place, a kind of canine Robin Hood or Scarlet Pimpernel. The very natural result was that I grew up worshipping the ghost of dog who died before I was born, a dog who was as real to me as the dogs of my own childhood.

The author, Max, and Chris Dorsey in a frozen Kansas landscape. Photograph courtesy of the author.

When I got my Chessie (from Linda Harger’s Northstar Kennels, sired by her legendary Fireweed’s Aleutian Widgeon), it was purely unintentional on my part. I wanted a Labrador, as a versatile waterfowl/upland dog, but had no idea where to get one. I was plying my trade in Hollywood in those days, starring as A.J., one half of the team of Simon & Simon, and in Hollywood, hunting is considered more deplorable than murder or pederasty, though not quite as bad as being late on the set. The only man I knew who hunted was a producer who kept his hunting a secret, and the only breeder he knew was Linda Harger. I called her to ask if she could recommend a Labrador breeder.

Linda is a great dog breeder. She is also no dummy. She told me she would need to meet me before she could recommend anyone to me or me to anyone. In those days, she was living between Los Angeles and San Diego, so I drove down, and she showed me around her kennels. Then we went inside to talk.

Linda is a great dog breeder. She is also no dummy. She told me she would need to meet me before she could recommend anyone to me or me to anyone. In those days, she was living between Los Angeles and San Diego, so I drove down, and she showed me around her kennels. Then we went inside to talk.

Widgeon was inside, the immortal Widgeon, and as we talked, he came and sat in front of me, gazing up at me as if I were the Beginning and the End. When he put his head on my knee, the deed was done, and before I left, Linda had a check for one of Widgeon’s pups. I have often wondered if Linda trained her grand old champion to go through this pathetic charade to beguile potential customers. Probably.

While waiting for my pup, I read every training book I could lay my hands on. Since I have always learned far more about hunting from my dogs than they have ever learned from me, it was a questionable use of time and money, but the one salient tip I retained was to pick a name that was short and could be yelled forcefully. I tried all kinds of possibilities, none of which resonated, so when Linda finally delivered my pup to me, on the backlot of Universal Studios, in front of sound stage eighteen, I was devoid of inspiration and named him Max.

Acting shares some characteristics with being in the military, and one of those is “hurry up and wait.” The advantage to going everywhere with me, studio and location both, was that Max had plenty of time and attention showered on him. Every day, 80 to 90 grips, dolly operators, set dressers, prop men, stunt men, camera men, sound men, gaffers, electricians, makeup artists, wardrobe men, drivers and dozens more, had to pet, kiss and make much of my young friend, and in the long hours of waiting, I played all those games that are the foundation of formal training: “come,” “fetch,” “sit,” “stay,” “find it.” By the time hunting season rolled around, my 10-month-old pup had a good head start on socialization and training.

Our first-ever hunt was as the guest of a friend of Linda’s, a professional trainer up in central California, in a flooded rice paddy, and the very first bird I shot over my young partner was a snow goose. I hit it hard, and it dropped about 40 yards out. To my dismay it popped up.

A wounded goose can be a formidable bird, and I didn’t want Max’s first live bird retrieve to be a bad experience. I looked at the trainer.

“Why don’t you send Sally out. I don’t want my pup to take a beating.”

He laughed. “He’s a Chessie. Send him out.”

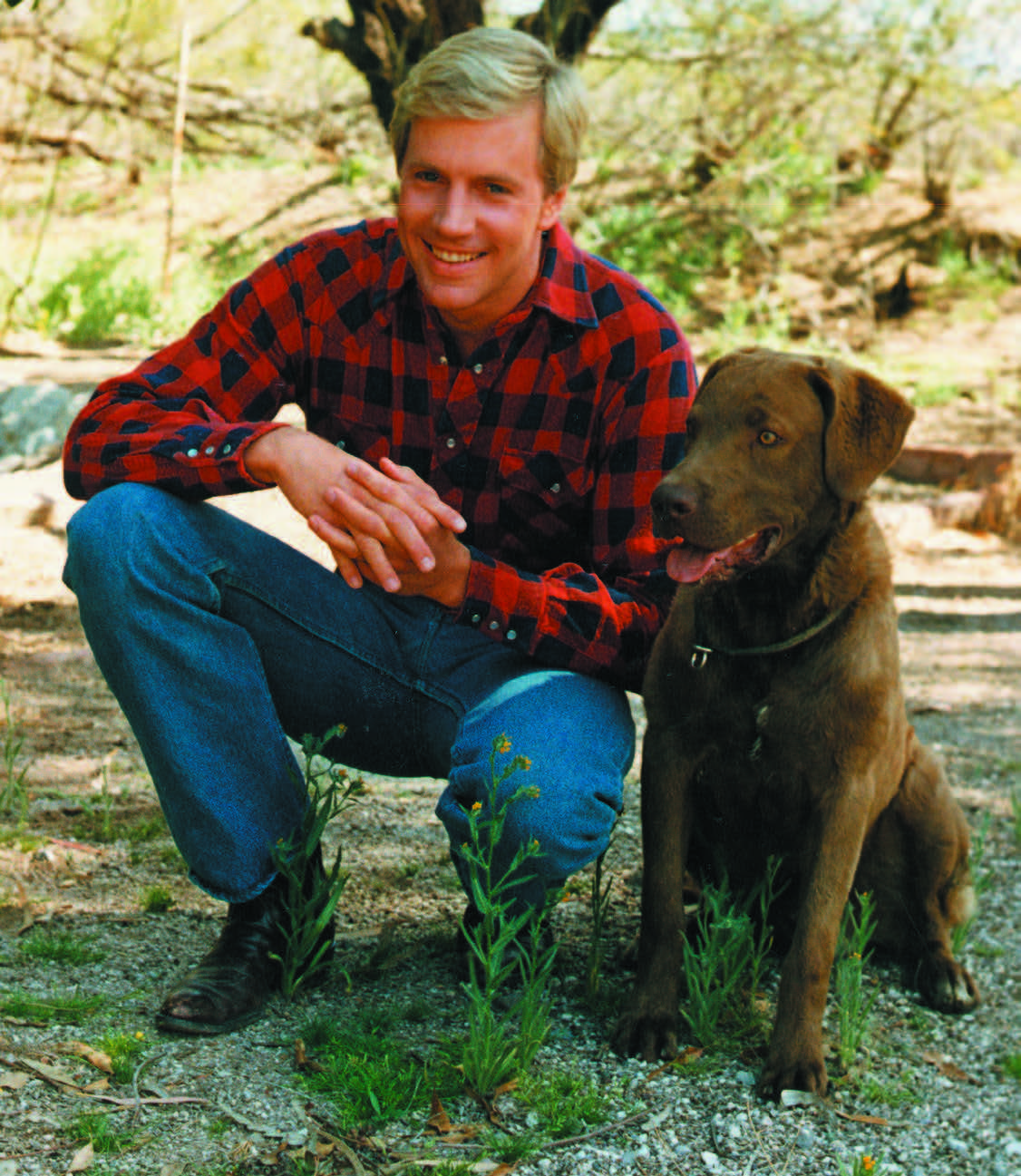

A young television star and a young Chesapeake by the name of Max. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Max bounded through the water, the very picture of eagerness and professionalism. The goose raised itself partially and whacked him hard on the nose with a wing. Max took a step back, but before my heart even had time to sink, he gathered himself and lunged in, grabbing the goose firmly by the body. Very firmly. When he delivered the goose it was dead, and from that first bird to his last retrieve in his 13th year, he never once delivered a live bird. He never mauled them; he never ate them; he just made damn sure he wasn’t going to get whacked again.

I shamelessly took advantage of this habit over the years. I’m a dreadful shot, and my many hunting partners have delighted in ribbing me about my many misses. But whenever Max and I hunted with someone new, I stunned them with my clean shooting. I never had to wring a neck; either I missed or I killed the bird clean. If I was lucky enough to have a good day, those strangers marveled at my ability, and I never corrected them. When you shoot as badly as I do, a little marveling is good for your ego.

I have been fortunate enough to have had many fine dogs, but the greatest, unquestionably, was Max. I hunted three different species of quail over him, ruffed and spruce grouse, pheasants, chukars, doves, band-tail pigeons and every species of waterfowl that may be legally hunted, and he never made me anything but proud. Gobsmacked, sometimes, but always proud.

The author and Max in a northern California marsh. Photograph courtesy of Chris Dorsey.

His only bad habit was his insistence on making the first retrieve. It made no difference who made the shot, you, me, the total stranger three fields over; if someone shot before me, and Max could hear it, that bird would be brought to me. After that, he would settle down and behave, but I have had to return many a bird and make many an apology.

The one exception to his “first-bird” rule came when he was very old, on his last hunt.

Several years after I left “the business,” as acting is known, I was hired to work one of my dogs at a private hunt club that was hosting a driven shoot for a party of multi-multi-millionaires. Since it would be physically undemanding, I took my old friend.

The shooters were members of a frightfully exclusive group that allowed the use only of classic side-by-side shotguns. Think Boss, Purdey, Holland & Holland, Piotti, Lebeau-Courally, David McKay Brown, Hartmann & Weiss—the kinds of guns that start in the high five-figures and careen quickly up into six figures. There were a few tacky high-grade Parkers and Model 21s dragging the tone down some, but for the most part, it was very, very refined. All the members wore traditional British shooting outfits, plus-fours and shooting coats in heavy Harris tweed, woolen shooting caps and knee-high wool socks.

The secret anarchist in me looked at all this with great interest. I was doing a lot of riding on southern and central California ranches, pretending I was a cowboy, and I had a pretty good idea of what would happen when the thermometer rose up into the high 70s. I also had a pretty good idea of what would happen to those woolen socks as members walked to their butts, the shooting stands that in the British Isles are made of rock, but in southern California are made of hay bales.

I was right on both counts. By the time we broke for lunch, each of the gentlemen in question was dripping sweat, and each of them had to spend the lunch hour painstakingly picking foxtails out of his socks. But I have to give them credit: not one of them complained or shed his coat; in their own refined, impractical, anachronistic way, they were tough and stoical. They were also phenomenal shots.

A driven shoot is considered to be one of the most challenging forms of shooting. I won’t call it a hunt, because hunting is a process of searching for birds, a cooperative venture between man and dog where the skills of each combine to make both more effective than either might be individually, but driven shooting deserves respect for the skills it demands. It also, at least for this particular organization, prompted a good deal of rivalry, and money was riding on the final tally at the end of the day.

The special celebrity guest at that long-ago shoot was a young lady who had recently become the youngest female gold-medal winner in the history of Olympic shooting, the legendary Kim Rhode, and to give you an idea of the difficulty of the shooting, she was not the best shot present that day.

In Scotland, driven shoots are conducted with beaters who march through the heather with dogs and sticks, driving grouse out before them so that, from the shooter’s point of view, the birds come screaming out of the sky at great heights and great speeds, and it takes truly extraordinary eye-hand coordination and years of practice to be able to cope with the difficulties of speed, distance and angle involved.

In southern California, heather and grouse are conspicuous by their absence, so pheasants were released on a high hill where the prevailing westerly winds had them flying at the outer edges of a full-bore’s capability and at speeds that required almost professional trick-shooting.

It was my first experience working my old friend and hunting partner as a non-slip retriever for other shooters, but I knew he would remain by my side, and as long as no other dog was fool enough to challenge him over ownership of an individual bird, all should be well.

At the first break, the guns retired to gulp down water (and pick foxtails out of their socks), while Max and I went out to do our duty. Max was one of the two finest retrieving dogs I have ever owned or even seen, and we quickly brought back all the birds my shooter had dropped, the guns returned to their butts and the shooting began again.

My shooter was a rotund little man who looked as if he had no more athletic ability than an avocado, but he was to his shotgun (a W & C Scott, and I would have happily murdered him to own it), what Lebron James is to a basketball. I tried to mark all the more difficult or distant birds, and when we broke again, I sent Max out to find the hidden ones while I picked up the ones I could see.

Happy author, happy Max on a pheasant hunt in South Dakota. Photograph courtesy of Chris Dorsey.

I thought at the time our pile of pheasants looked considerably larger than I had remembered, but I put it down to the excitement of the moment, and after all, it wasn’t as if I had been keeping count or anything.

It was during the morning’s third and final round of shooting that I caught movement out of the corner of my eye. A Chesapeake that looked suspiciously like Max was quietly picking up a pheasant out of the pile of birds behind the next shooter about 50 yards away. I hadn’t realized there was another Chessie working that day and I glanced back at Max—only there was no Max behind me. I was so confident of my friend’s steadiness on a down-stay that it had never occurred to me to put him on a leash—leash my dog?!—and he had evidently decided if what the boss wanted was pheasants, he would, by God, bring me pheasants. I had to choose whether I wanted to confess my dog had been stealing birds and tipping the gambling stakes in favor of my shooter, or whether I wanted to be a party to cheating.

I have always prided myself on doing the right thing and being scrupulously honest, but I had to weigh those virtues against my ever being invited back to that particular club. I made the difficult moral decision to put Max on a leash and keep my mouth shut. As it turned out, even with Max’s, um, assistance, my shooter did not have the high tally for the day. Either someone else farther up the line was a better shot, or he had an equally unethical dog.

In the 13 years between that first and last hunt was a life made infinitely richer—both in the field and in the home—by his presence. We hunted from the Pacific to the Atlantic, and from the northern plains to southern marshes, and had all the grand adventures and misadventures common to itinerant hunters. But Max stood out as much as a family member as he did hunting partner.

When I taught my sons how to play baseball, pitching a tennis ball to them for practice, Max would sit behind me and play shortstop, frequently catching the ball in the air, always retrieving the ball to hand before resuming his position, with his ears cocked, his eyes full of enthusiasm.

For two years I lived in New Hampshire in a little village on the Connecticut River. On hot summer days, I would take Max and my children down to the river to swim. My youngest daughter, then only four or five, is disabled, so I would put a life preserver on her. She would grab Max’s tail, and my old boy would happily tow her around, hour on end, like the lifeguard he was, giving a little girl the greatest physical freedom she would ever know. He was that kind of dog.

He was also the first dog whose death I had to face. All the dogs of my childhood had died while I was away at school, or on a camping trip or overseas. But Max was the one I had to take to the vet myself. We sat in the little room—rooms of healing, rooms of death, which is sometimes the only healing possible—and I stroked his thick soft ears as I had to confront the horrible disparity between a man’s life and a dog’s, and the even worse irony that man should be given the role of God in that relationship, for we are so woefully miscast. When it was over, I felt something inside me break, a literal sensation of something gone as irrevocably as my old friend.

I dream still of dogs I shared my life with many decades ago; most of those dreams are happy, or at least bittersweet; a few anxious as I attempt the impossible save, the impossible rescue, the impossible search. But there are also the other dreams, the ones where I awaken sobbing bitterly, for love lost too soon, too soon, for a lifeguard with an uninspired name.

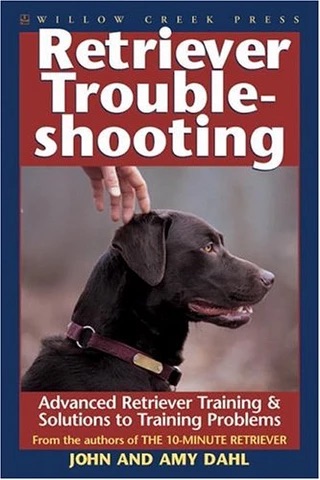

In this book, nationally-recognized retriever trainers John and Amy Dahl (The 10-Minute Retriever) tackle advanced training methods and problem-solving using a dog’s innate strengths to compensate for its weakness. They discuss how dogs learn at an advanced level while encouraging readers to tailor their training so the dog keeps progressing. Training topics include: how advanced training applies to hunting and to competition; blind retrives; achieving range and multiple blinds; handling; hazards and formidable obstacles; more disciplined lining; marking; and the use of e-collar in advanced field work. The authors also discuss good general practices and individuality in training, along with specific real-life dog training stories that help readers see how they deal with unique problems. Shop Now

In this book, nationally-recognized retriever trainers John and Amy Dahl (The 10-Minute Retriever) tackle advanced training methods and problem-solving using a dog’s innate strengths to compensate for its weakness. They discuss how dogs learn at an advanced level while encouraging readers to tailor their training so the dog keeps progressing. Training topics include: how advanced training applies to hunting and to competition; blind retrives; achieving range and multiple blinds; handling; hazards and formidable obstacles; more disciplined lining; marking; and the use of e-collar in advanced field work. The authors also discuss good general practices and individuality in training, along with specific real-life dog training stories that help readers see how they deal with unique problems. Shop Now