Will the Tanzanian government succeed before the country surrenders too many of its wild lands and these ecosystems succumb to over-grazing and the inevitable and irrevocable desertification that follows?

We watch as a lone bull elephant heads for a water hole but encounters several hundred Maasai cattle blocking its path. The elephant begins chasing the herd like an outsized Australian shepherd, which prompts the Maasai tending the bovines to shout at the spirited bull that then turns its attention to the lone herdsman. The shepherd sprints away from the irritated pachyderm, leaving the cattle to momentarily fend for themselves. The elephant has had enough, however, and changes course to locate a different pond, presumably one not encircled by cattle.

Such an encounter is common in this part of northern Tanzania. For Harpreet Brar, a fourth generation descendent of Indian immigrants who has operated a hunting concession for more than 20 years, the population explosion of Maasai cattle in recent years is creating a crisis for the region’s wildlife. According to one report, there were some 19 million cattle in the country in 2010 and now they number roughly 30 million, which doesn’t include millions more goats and sheep also impacting the landscape.

Grazers like Cape buffalo and zebra compete with Maasai cattle for the region’s limited supply of grass. JOHN MACGILLIVRAY, DORSEY PICTURES

For the Maasai, cattle act as a currency that’s used to trade for virtually anything they may need or want — including wives, if the price is right. The problem with this compounding bovine bank, however, is that it consumes ever more land — and they’re not making any more of it, to paraphrase Mark Twain. The same grass needed by cattle also serves as the primary food source for many wildlife species, and there simply isn’t enough to go around — especially in drought years. Then there’s the staggering amount of water needed to sustain millions of cattle across a relatively arid landscape.

“It’s early in the season and already the cattle have eaten much of the grass that the buffalo and other wildlife will need to survive until the rainy season that’s still several months away,” says Brar as we drive through his hunting territory, encountering an astonishing number of cattle herds along the way. “This is an area designated for hunting by the government, but the Maasai have moved in for the grass and water, so what is the wildlife supposed to do?”

Like much of Africa, Tanzania’s human population is growing exponentially — from roughly 8 million in 1950 to nearly 68 million in the country today. For Brar, the demands on natural resources and wild lands has hit an inflection point. While hunting is an especially important economic driver for the country — providing roughly four times the revenues generated by photographic tourism — the challenge for Tanzania is how to preserve the cultural traditions of the indigenous Maasai, while at the same time providing for wildlife that draws thousands of visitors from across the globe each year. Exacerbating the problem is the fact that the Maasai’s barter cattle economy generates little income for the country, and the domestic stock compete with wildlife interests that are the basis of the nation’s tourism economy.

Wildlife tourism is a leading economic driver for the nation of Tanzania. JOHN MACGILLIVRAY, DORSEY PICTURES

Furthermore, according to a 2022 World Wildlife Fund report, Africa has seen a 66 percent decline in biodiversity, one of the most impacted regions on Earth. Human population growth leading to habitat fragmentation and degradation is at the root of these declines. For Brar, the rapid increase in cattle populations and their impact across vast regions of Tanzania is simply not sustainable.

“Hunting provides funding for anti-poaching efforts, and it creates the financial reason to keep habitat healthy,” says Brar. “And that benefits a wide assortment of species, most of which are not hunted. It also provides higher quality photographic experiences as wildlife from hunting concessions moves freely back-and-forth between parks and photographic areas.”

According to a 2023 Scientific Research economic report, moreover, the total value of hunting concessions is far greater than direct fees paid to the government. In addition to those funds, the areas provide a biodiversity boon as well as delivering other direct benefits including timber and fuel wood collection, fishing, fruit and honey collection, and limited agriculture. Indirect benefits that are key to sustaining optimal biodiversity include erosion and flood control, soil conservation, storm protection, air and water purification, and genetic diversity among many other values.

Thousands of visitors flock to Tanzania each year to witness scenes like this.JOHN MACGILLIVRAY, DORSEY PICTURES

“The good news is that the Tanzanian government is aware of these issues and is working to solve the problem,” says Brar. But the question remains: Will they succeed before the country surrenders too many of its wild lands and these ecosystems succumb to over-grazing and the inevitable and irrevocable desertification that follows?

Therein lies the urgency of the problem and why the stakes couldn’t be higher for a nation whose fate is tied to the health of its charismatic wildlife and the foreign currency it generates.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in Forbes.

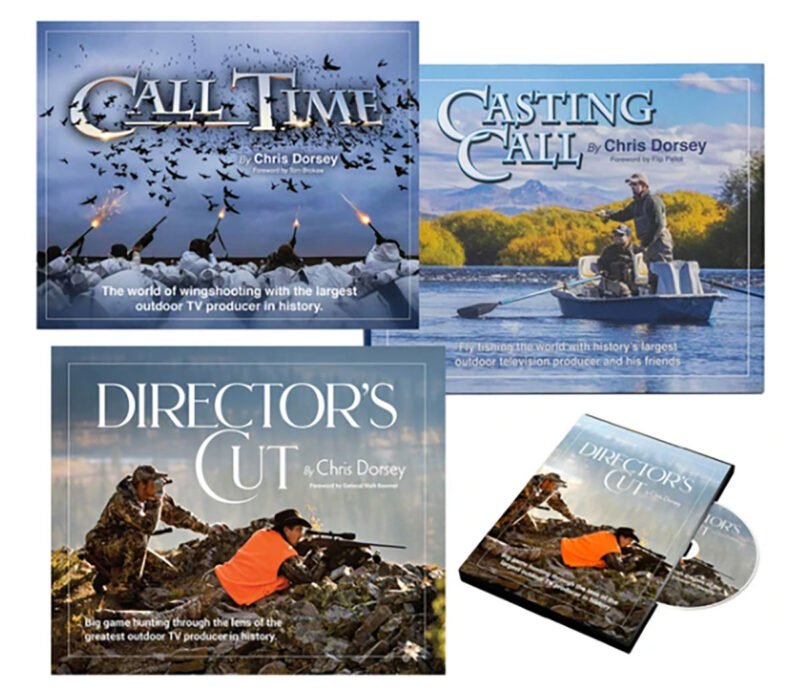

Featuring Casting Call, Call Time and Director’s Cut this bundle includes a book and film production more than 30 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of wingshooting, fly fishing, big game hunting and the great outdoors. Each large-format 250+ page book includes a DVD with corresponding film shot on location for every chapter. Buy Now

Featuring Casting Call, Call Time and Director’s Cut this bundle includes a book and film production more than 30 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of wingshooting, fly fishing, big game hunting and the great outdoors. Each large-format 250+ page book includes a DVD with corresponding film shot on location for every chapter. Buy Now