Tom Modin doesn’t see himself as much of an artist, but his hand-carved, hand-painted decoys say otherwise.

Tom Modin doesn’t see himself as much of an artist. “The last art class I had was in eighth grade,” he said with a laugh. But on a sunny fall day, the ultimate judges gave Modin high marks for some of his artwork.

As a small flock of redheads suddenly flew into sight over a pond in northwest Missouri, Modin blew loudly into his duck call, then watched as the birds banked and circled the decoys he had carved and painted. They cupped their wings and headed straight for a string of redhead imitations.

Modin’s black Lab, Max, whimpered in excitement as the ducks drifted down. Modin and three of his friends hiding in layout blinds along the large pond also waited in anticipation.

When they got close, Modin shouted, “Take ’em!” and several shotgun blasts rang out. Two redheads tumbled to the water, and Rex bounded out to do his job.

At sunrise, a spread of Tom Modin’s homemade decoys are arranged on a pond in northwest Missouri.

“They came right in to those redhead decoys,” said Modin, 42, who lives in Kearney, Missouri. “I just love that when we can shoot ducks over decoys that I made.

That’s all Modin uses when he hunt—decoys that either he or his friends carved. It’s an old-fashioned way of hunting, but they wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Years ago, hunters couldn’t go to the store to buy their decoys. They carved and painted their own. That’s what we do today.”

Where Modin ventures out, mixed-bag hunting is the rule. He fashions his decoy spread accordingly to ensure it looks realistic.

“We put out decoys of all the types of duck I have seen here: mallards, redheads, green-winged teal, goldeneyes, ringnecks,” he said. “It looks a lot more natural to the ducks than just tossing out a few dozen mallard decoys.”

The decoys certainly caught the ducks’ attention on this trip. The hunters shot an assortment of ducks, all of which came in to the species Modin tried to imitate when he started carving.

Tom Modin’s hand-crafted decoys have fooled many ducks into flying within shooting range of hunters.

But that’s not unusual; not for Modin. Since he started carving he has seen the wonders these wooden imitations can perform.

“When we hunt ducks, this is all we use: hand-carved, hand-painted decoys,” he said. “We don’t use motion-wing decoys or anything like that.

“I’m not saying they work better than all the modern decoys on the market. All I know is that we’ve shot a lot of ducks over these carved decoys.”

Modin got started more than ten years ago when he purchased a few older decoys and started researching them. He was intrigued with the art of carving and painting decoys, so he set out to make a few of his own.

He ordered an instructional DVD, carved a goldeneye decoy out of cork, then meticulously painted it.

“When you first do it, you think it’s the most beautiful decoy in the world,” he said with a laugh. “When I look at it now, it’s pretty rough. But it was a start.”

Modin carved several other goldeneyes and green-winged teal and was excited about the success he found. Those decoys are still part of his spread.

“We’ve shot a lot of ducks over those decoys,” he said.

Tom Modin rearranges his hand-carved decoys during a recent duck hunt.

Today Modin carves most of his decoys out of basswood, although he still uses cork and northern white cedar on occasions. He uses artist oil paint for the finish.

He tries to duplicate the ducks in a variety of relaxed poses—head down, feeding, heads tucked under a wing, etc.

He follows a routine when making the decoys. He carves the main shape of the bird, the head and other parts, then hollows it out so that it is buoyant. He glues the pieces together, then seals it. After that he applies primer and several layers of paint.

Modin will trade decoys with other carvers, so his spread is made up of a variety of artwork. He also sells his decoys through his hobby business, Missouri Custom Outdoor Products, but he isn’t in it to get rich.

“Whenever I take a kid out hunting, I try to give them one of my green-winged teal decoys afterward,” said Modin, who is a nurse. “For me, this is still a hobby. But I have a lot of fun with it.”

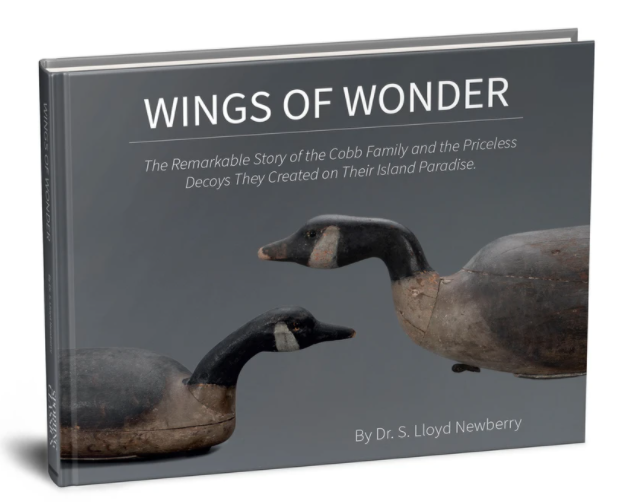

Nathan Cobb and his family were iconic figures in the maritime and waterfowl gunning history of North America. With an ancestry and gene flow directly back to Plymouth Rock, Nathan’s father was a Cape Cod whaler and shipbuilder. Seeking a warmer climate for the women in his family who were suffering from tuberculosis, Nathan sailed south to homestead on Virginia’s Eastern Shore.

Nathan Cobb and his family were iconic figures in the maritime and waterfowl gunning history of North America. With an ancestry and gene flow directly back to Plymouth Rock, Nathan’s father was a Cape Cod whaler and shipbuilder. Seeking a warmer climate for the women in his family who were suffering from tuberculosis, Nathan sailed south to homestead on Virginia’s Eastern Shore.

For their use in hunting, they crafted their own wooden decoys. Though natural and man-made disasters brought an end to their island paradise, these wonderful and highly coveted replicas of the many species they hunted cemented their fame among historians and folk art collectors for centuries to come.

The author traces this fascinating story through three generations of the Cobb family. It’s a chronicle that historians and folk-art collectors will find both educational and enjoyable. Buy Now