From one world to another in a couple of blinks.

The first boat heads out. Native fishermen crowd the beach and watch to see if they make it through. We idle upriver, then circle to wait our turn. Ahead is a quarter mile of choppy, mocha-stained water. Five-foot waves roll in, some white-capped with spindrift blowing off their tops. The river mouth, over four city blocks across, has treacherous sandbars in the shallows. If the waves are too high, you go up in the air then plunge down to smack the bottom. The boat capsizes, or big breakers spill in and you flounder.

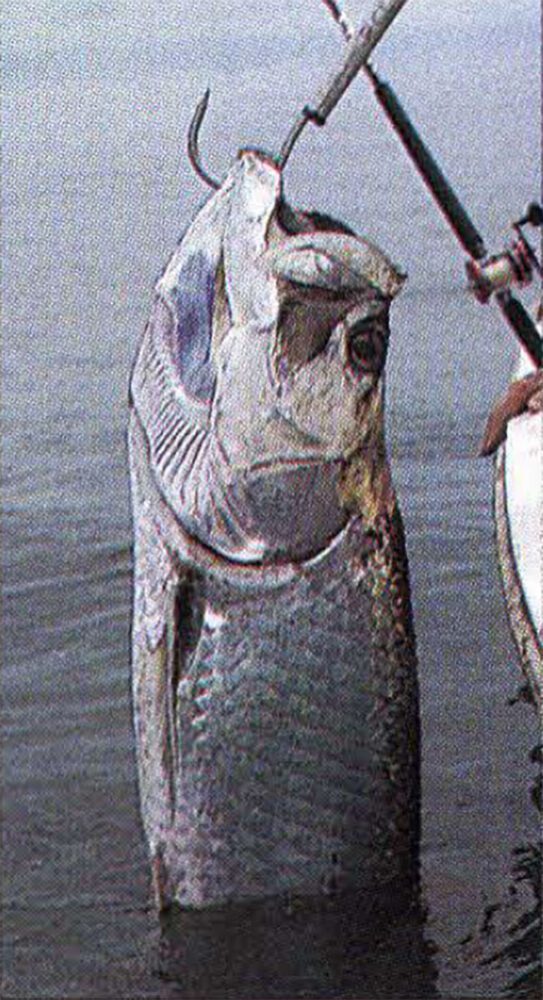

60 pounds of silver.

The first boat struggles through. We’re up next. Our Coast Rican guide yells, “Hang on!” He swings our bow toward the churning boil, guns into the first wave, climbs up and over the crest, then cuts the motor and slides down the other side. Up we go again, again and again. Spray pummels my face. I wipe it with my hand, feel grit on my skin and taste salt. We slide sideways. I almost panic.

We labor on. Over the top, down the side, into the trough, up again. Gradually the waves flatten. The water still heaves but is smooth. We are out of the mouth of the Rio Colorado, out to where massive schools of tarpon roam.

“You’ve got to get out to sea,” a friend told me before my first trip to Archie Field’s Rio Colorado Lodge in 1986. No problem. I had calm water, no jolting whitecaps, a millpond sea. Not so on my second trip in 1989. The wind was up, waves were high and spaced close together. Words like “reckless,” “audacious,” “Fool!” came to mind. But once we ran the gauntlet, fishing was fabulous. We sighted funneling birds, sped to them, circled and cast into frantic bait on the surface. I hooked half-a-dozen 30- to 60-pound tarpon every time we went to sea.

A 60-pound tarpon comes within inches of joining the author in his boat.

On the first afternoon of this trip in May of ’93, conditions are different. We ride all the way out to blue water. When I look back, land is a thin pencil line. Sky conditions are weird. It is leaden in the west, except where the sun pierces holes in clouds and spotlights the sea. My bait barely hits the bottom when I feel a slashing take, set the hook and a big tarpon is on. He goes airborne like a Polaris, crashes the water, spews diamond spray and leaves a 12-foot crater. The first run is spectacular. He twists across the horizon, surface-walking, scale-rattling, head-shaking. I count five jumps, bow to the King and heave him closer and closer. The line veers off to port soI turn my fighting chair.

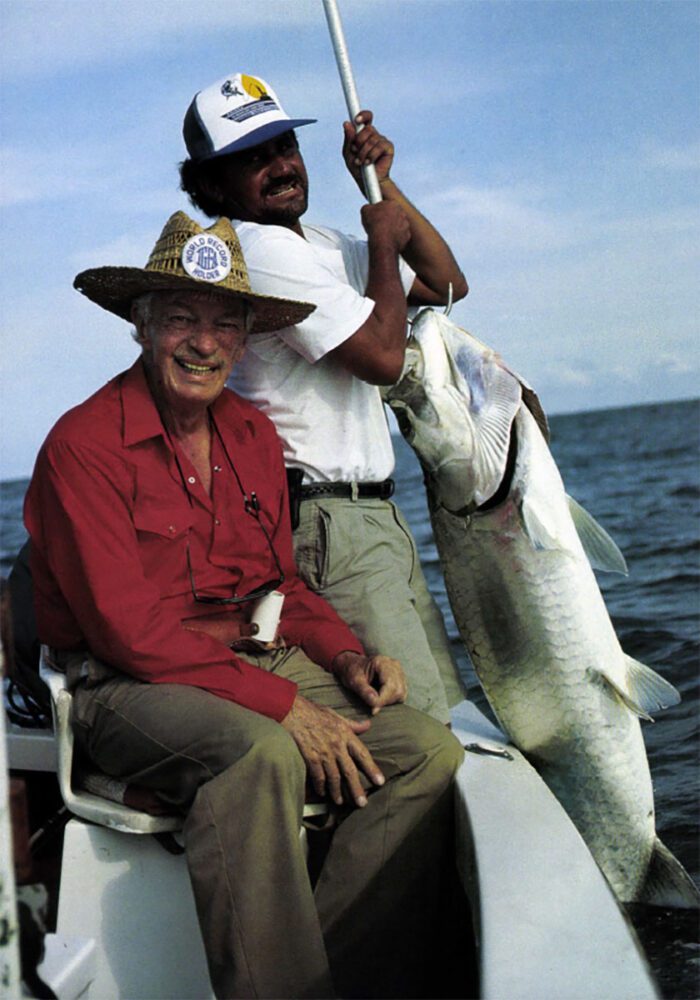

Then it happens. The sun is angled just right. When I look down it is like seeing through the transparent wall of a vast aquarium. Hundreds of huge tarpon charge through the water below. Bathtub sized! White porcelain! Glowing silver! Going like missiles! Amazing! What an experience. Whish! Suddenly the legion is gone. The sea is clear. I gasp with excitement but have no time to reflect, because I’m still hooked to a bruiser and have to bring him in. Tim yells, “I saw ’em too!” He guides his boat near and takes some great shots of the tarpon as it leaps between us. Finally we ease the fish against the boat. Guinder Clark, our 33-year-old guide who goes by “Gunga Din,” gaffs the monster’s lip, lifts him for a picture, then pumps him up and down until he floats off the hook.

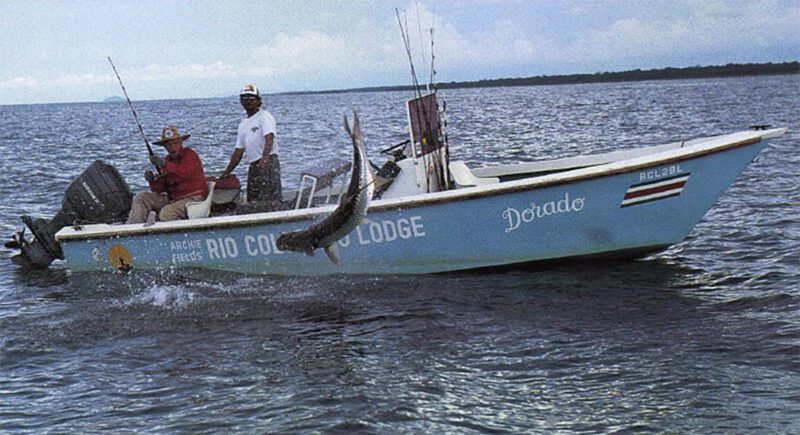

I appreciate fishing out of a larger boat. This one’s a 23-footer, seven feet beyond the boat I rode in 1986. Extra length is a comfort when you confront the river mouth and navigate the ocean. The fiberglass craft is called a Sea Boat, made in Costa Rica. It has a center console and a 76HP Mariner engine. There is a fairly large well and a forward deck for stand-up casting. Its fish finder is a Lowrance LM5-200, which pings like a steel drum in a hailstorm. Gunga Din says, “They’re down there,” and points to lumpy snow covering the scope. “We’ll get our share.”

Doug Johnson and his Costa Rican guide. Guess who s having the most fun.

It’s like going home again to be back at this camp. I almost feel like I grew up here, came of age, you might say. It is my theory that no angler reaches maturity until he brings his first tarpon to the boat and pats the noble fish’s muzzle. A kiss is optional. This is a rite of passage similar to a Masai warrior spearing his first lion or an el-Molo adolescent knifing his first hippopotamus. Unhappily for them, present conservation laws in much of Africa dictate that neither tribesman can achieve his manhood legally nowadays. But here at my favorite lodge in the world, a “Silver King” can still be reeled in for the ritual.

I actually wanted to come back as kind of a tribute to Archie Fields after his recent death and frankly, to be sure things hadn’t changed too much. I wanted to return to Samay Lagoon, where I hooked a 95-pound tarpon on light tackle and played him for over half an hour. I remember practically lying flat in the boat, wheezing, struggling to hang on with the fish swimming close, wheezing, looking at me across the water with one baleful eye and both of us wondering why we were doing this to each other. I had hoped to release him, but the guide said people in the village needed food. We had respectful pictures taken together. He was handsome and stretched longer than I am tall.

This trip I want to indulge in sensory nostalgia, to listen as squeaky boards tell me someone is passing my room in the dark. I want to sniff the salty air at night and just before sun-up, catch the first cook fire smoke as it wafts through the little village of Barra Colorado-Sur. At dawn I want to see a lemon sunrise glitter on the chocolate river and paint a bleary tint on green orchids in russet pots perched every three feet on the rail along the promenade. Let me hear the first outboard motor grind in the distance, and count while my ceiling fan circles and goes “wooop.” I yearn to find that everything is friendly, familiar, absolutely old shoe, and that I’m back home again.

The guide, Guinder Clark, with a catch.

Rio Colorado Lodge expects high water, which is why it’s built on six-foot stilts. Covered walkways lead to rooms for 36 guests scattered around the area. It’s kind of a maze but you get used to it. One reason for the disarray is that wild winds rip through now and then, and yank corners off the place. They are rebuilt by people who appear to have lost the original plans. On this trip I notice the once-prominent weighing and cleaning station on the east end has been switched to the west end and miniaturized. Actually, since catch-and-release emerged, weighing has lost its cachet. A scale is almost superfluous. “What happened?” sez I. “Hurricane!” sez they. Enough sezed.

The dock stretches along the river’s edge not far from the sea. Boats are tied in roofed-over slips that remind me of a PT boat pen I visited outside Hollandia in New Guinea over half a century ago. In the center of the dock is the camp store, and a lounge area juts out over the river. There are four, free-standing, double hammocks on the deck, among lots of chairs and rockers. The prime spot is out on the lip facing the water. I made it my “office” for morning coffee and evening rum. Breakfast happens here and tall tales are told. Other meals are served buffet-style off the pool table in the bar or family-style in a big upstairs dining room. The food is outstanding and the devil of a temptation for dieters.

This afternoon Tim Hardin, my non-fishing/photographer friend, is in a second boat so we can shoot some classic tarpon jump-shots. I’m giving him plenty of opportunities and he’s burning film. It is hard to believe just the day before we hugged our wives at Indianapolis International and boarded an American Trans Air for Florida. From there we took a 727-200 run by Aero Costa Rica, a fledgling airline that has quickly learned to do very well by its passengers. We had some afternoon and evening hours in San Jose. I never have enough time to properly explore this charming, energetic city with its smiling people. The next morning we headed north over a circle of volcanoes for a scenic ride above the jungle to the northeast corner of the country.

Built on six-foot stilts to cope with constantly fluctuating water levels, Rio Colorado Lodge is just a short flight away from San Jose on the Pacific side of Costa Rica.

At touch-down we are greeted by Todd Staley, the lodge manager. He gained a fine reputation around Largo, Florida, as a guide, newspaper columnist and inventor of fishing baits. Todd is here to help Dan Wise, the new owner, preserve the high quality of the lodge. I liked them both immediately. Wise, a young lawyer from Hattiesburg, Mississippi, told me, “I don’t see any reason to drop Archie Fields name from the lodge logotype. He built the place and hosted hundreds of anglers over 20 years. They knew and liked him. The name stands.”

The next morning we struggle out of the river mouth, turn north and head toward Nicaragua. We cruise toward a point about 30 minutes ahead. The beaches are black volcanic sand laced with Jaleo palms. Gunga Din says the natives smoke their small seeds in pipes. The tall palms are Royals, planted for the coconut harvest. Salt in the constantly fuming mist burns the leaves and turns them brown.

We round the point and in about 10 minutes come to a red sign on the beach. This is the casual, no-barriers, no-guards border between Costa Rica and Nicaragua. Plenty informal, I’d say. Just beyond is a river mouth similar to the Rio Colorado, but not as shallow. This is the mighty San Juan which flows east from Lake Nicaragua, near the Pacific, across the country to the Atlantic. We enter, turn north for a mile between sandy banks, then west up the river.

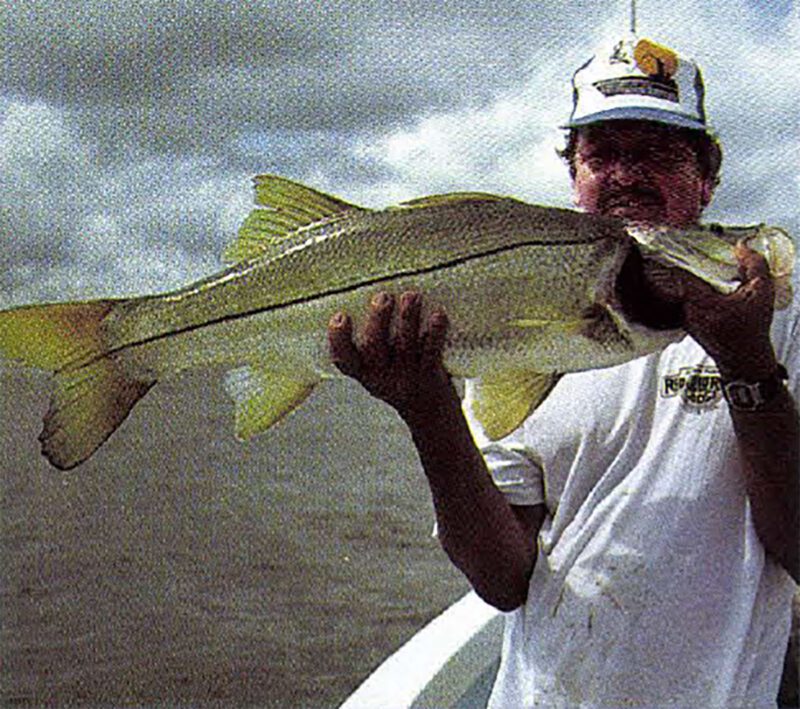

Houdini sneaking a snack.

In another mile there is a collection of shacks along the south shore. Gunga Din says the original settlement called San Juan is miles from here. It was fought over during the war; mines were planted, bombs dropped and some did not explode so are still live. The townspeople moved out and, afraid to go back, they started a new settlement. Tim photographs a sign that says, “Welcome to Greytown.” We bump the muddy shore in front of some unpainted, wooden buildings. A youngish man in official black pants, white shirt and billed cap charges us $25 for a license. The guide says it will go to help school children with books and supplies. Everybody pays because the area is kind of a wildlife refuge.

We turn around and go back out to the river mouth to fish. Big waves roll in but break about one hundred yards away. Still, it is very choppy.

Using both fly and bait-casting gear, we get six tarpon hook-ups and boat several 60-pounders. I finally snag an 80 -pounder that really puts me to work. Right after we get him in and off, I change to a medium-action rod, a reel filled with 120-yards of 12-pound test line, and a seven-inch plug. As you can tell, I’m rigged light and baited for snook. Bam! A tarpon takes it on top! This is a fish I’ll never forget. He fires across the water like an IndyCar in the grand-stand stretch. I’m hooked to a 50-pound flying fish that skips like a flat stone. I tighten the brake, try to palm the reel. Nothing stops it. Line won’t break. The tarpon makes a screeching run out to sea and rips off every inch of monofilament. I’m spooled. I feel a yank when the tag end snaps off the reel. That’s it. Long gone except for a vacant feeling in the pit of my stomach. A one-minute event. But what a show!

The lure that works best here looks like a finger-length of steel reinforcing rod. It has an interesting story. Originally called the Sea Hawk, it was invented by a man named Porter as a Florida snook lure. Somebody brought a half-dozen to Rio Colorado Lodge and found it also worked fine for Costa Rican snook. What’s more, it turned out to be a humdinger tarpon catcher. Porter sold the baits for many years, then quit producing them. They couldn’t be found at retail outlets. To fill the gap, Jack Walker of Adkins, Texas, started to manufacture them under the name Coast Hawks. His lures come in ten colors with one- and two-ounce weights. The most popular here are the black tiger stripe, the yellow tiger stripe, and the redhead with the white body (my choice.) To fish them you cast out, let the bait drop to the bottom and jig slowly as you drift. Easy up, pause and easy down. Don’t jerk, not yet. Wait for the slightest hit, then give the rad a killer yank to set the hook in a cinder-block jaw.

One morning we went upriver and tried the Agua Dulce (“sweet water”) lagoon. I caught perfectly shaped nursery tarpon from six to twelve inches long on my flyrod. I also hooked what Gunga Din called a “bluegill” or azul mojarra (mo-HAR-ah). Those with red peacock bass stripes are mojarra rajah. A second variety was the running, bouncing machaca (ma-CHAA-kah) that I’d have on for a minute-and-a-half before it’d ricochet off. I also landed small “tarpon snook,” which have bigger eyes than regular snook and an even more prominent lateral line down the side. It’s a blast to sample the variety.

The author works a quiet lagoon for “tarpon snook ” and other toothy fish that inhabit the brackish backwaters.

Tim and I also got a kick out of the camp petting (at your own risk) zoo. The gangway leading from the dock to the bar is lined with cages of small animals and brightly plumed, very vocal, tropical birds. Tim took pictures of Baby the trunk-nosed tapir eating bananas. It is a homely beast, kind of a combination infant elephant and Poland China hog. Then there is Houdini, a white-faced monkey who picks every lock they put on his cage. He roams the rooftop and swings from the beams until somebody notices he has sneaked back behind his bars to find a square meal. They slam the door on him and the game starts again.

Gunga Din says, “The best time to fish for tarpon is all year around. Some say January through June is best because the ocean is down, but if it is rough you can still find a lot of fish in the river. The largest tarpon ever caught around here was hooked on a handline at the river mouth. It weighed 187 pounds.”

I didn’t catch it. But I did just great this trip and had a ball. To review: My average tarpon was about 70 pounds, bigger than the other two trips. The first day I had 15 hookups with five to the boat. The second day, I had 28 with 12 to the boat. Among them were fish that weighed 70, 80 and 90 pounds. On the third day I had 16 hookups, brought nine to the boat, among them several 60s, and my best, a 95-pounder. Fabulous!

I was just getting revved up good when somebody said, “Time to go.” I yelled, “No, not so sooooonn!” The flight back to San Jose was 35 minutes — from one world to another in a couple of blinks. But hey, I can get back just as fast.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1994 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now