A cane pole, whether used from shore or in a boat, is wielded by a simple, graceful motion in which the angler lobs the baited hook.

The image is as enduring as it is appealing, something straight from a Norman Rockwell cover on an old Saturday Evening Post. A barefoot, freckle-faced country lad walks down a dusty lane with a bait bucket in his hand and a cane pole over his shoulder. Headed for a favorite fishing hole, he’s as footloose and carefree as a frolicking puppy. Those fortunate enough to have enjoyed such experiences in a time of simpler days and simpler ways can look longingly back to them, while for others such images provide a bit of that comforting nostrum known as nostalgia.

Or perhaps when you think of cane poles another vision comes to mind. It is one of a battered old car or pickup truck bumping down a gravel road with a passenger-side window open. Several cane poles, all of them decorated with colorful bobbers, stick out the window. Inside the vehicle, passengers, perhaps a father and his children or maybe a bunch of friends, smile as they anticipate good times to come at the old fishing hole.

Sadly, I must acknowledge it has been years since my eyes have feasted on sights of this sort. Still, this vanishing aspect of the sporting scene is offset by glad realization that it is still possible to open a window of memory into youth and yesteryear. For that matter, with a modicum of gumption and a reasonable amount of effort, you can resurrect cane pole days.

It isn’t necessary to drink from the fountain of youth to do so. Cane poles remain as functional, and as much fun, as they ever were. With that squarely in mind, let’s look at some of the ways in which fishermen have long successfully plied this simple, satisfying angling tool. A logical starting point comes with the manner in which cane poles have been most frequently used over the years—for bank fishing.

A cane pole, whether used from shore or in a boat, is wielded by a simple, graceful motion in which the angler lobs the baited hook (usually, though not always, with a bobber affixed to the line above it) to a likely spot in the water. With some practice this can be accomplished with remarkable precision. The only real limitation is reach—the fisherman can get his bait in the water no farther than a distance just over twice the length of his pole. Nicely offsetting this shortcoming is the fact that a cane pole with a short length of line hanging from its end is ideal for poking into tight places such as beneath docks and piers, along shorelines with overhanging brush or in the midst of log jams or flooded timber.

Bedding bream, for example, are notorious for spawning in places where a cast with a spincasting or fly rod faces the likelihood of getting hung up. But the length of a cane pole lets the fisherman hold it above the detritus on the surface and drop his cricket or red worm precisely where it needs to be. When there is a bite, and there is a real expectation this will happen, he hoists the fish directly into the air rather than having to worry about weaving and working it through limbs, stumps or other impediments.

Cane poles, although more often than not used while being hand held, also lend themselves to being “set” with the butt end jammed into the mud or sand and propped up in a forked stick. That allows the angler to tend multiple set poles aligned conveniently along the bank. Often this will be done while the angler wields a handheld cane pole. It is a fairly simple matter, especially after one has done it a few times, to lay a pole down and rush excitedly to the set one that is getting a bite. If perchance there are simultaneous bites, and this sometimes happens with bedding bream, spawning crappie and summertime catfish, the ensuing “Chinese fire drill” is just part of the fun. There will be time enough later to deal with tangled lines and crossed poles.

A variant on this multi-pole approach is crappie fishing utilizing a “spider” rig. The name comes from an arrangement of poles extending from all sides of a boat, giving it an appearance similar to the legs of a spider. Spider-rig fishing involves much the same restful, relaxing ease angling as does idling on a shady bank waiting for a bobber to bounce, but another cane pole technique involves plenty of energy expenditure.

A cane pole works well for warm-weather wading in creeks or even sizeable rivers where there are shoal areas with depths of just a foot or two. The fisherman eases along, lobbing his bait or lure into likely spots, then deftly working it with the current or into inaccessible places that might be all but unreachable with a spincasting rig. This can be done with a float or through “tight lining,” where the angler maintains a taut line as the sinker on his rig bounces along the stream bottom. In slower water, a slight lift and drop of the pole’s tip suffices to change the hook’s position.

This technique works for all sorts of species—trout in mountain streams, channel catfish in shoals during the heat of summer, panfish in deeper pools or slow areas of creeks or even bass. I have fished for trout all my life and been privileged to watch dozens of skilled anglers in action. Without question, the single finest hand at catching these inhabitants of clean streams and wild places I’ve ever observed fished wet flies wielded with a length of monofilament at the end of a cane pole.

Perhaps the most interesting of all cane pole techniques involves the type of fishing colloquially known as doodlesocking or jiggerpoling. In this approach, a fisherman uses a cane of appreciably greater length than normal—sometimes as much as twenty feet if the individual handling the pole is strong enough. A short length of monofilament holding a large surface plug, a jig-and-pig rig, plastic worm or an actual piece of a pig in the form of pork rind is attached to the business end of the pole.

The word “finesse” isn’t in the doodlesocker’s vocabulary. It’s a matter of getting a lure into or near heavy cover along shorelines, amid flooded brush piles, adjacent to lily pads or moss beds, among log jams, alongside boat landings or at the edge of riprap then making a ruckus with it. You can keep the lure precisely where you want it, imparting back-and-forth action all the while, for an extended period of time. This is impossible with any cast-and-retrieve outfit. Strikes from bass, normally the target quarry, are often dramatically sudden and splashy. Expect misses, but often you can put the lure back in place and the fish returns for another go-round.

Once a fish is hooked, it is not played in the traditional sense but brought to the boat hand-over-hand. Once hooked by a skilled doodlesocker a bass may not touch the water again until it is suspended from a stringer. Doodlesocking is a two-man operation, with one individual wielding the cane pole while the other quietly poles a boat or paddles a canoe, always trying to be just the right distance from the spot being worked by the fellow doing the fishing. It can be quite effective for night fishing, especially in times near a full moon when there is enough light to allow anglers to see the spots they want to fish. Because of the necessity of getting close, the technique is more effective when water is murky.

From fishing on hot, lazy days while half-dozing in the shade to operating in the middle of a boat outfitted with a spider rig, from jiggerpoling excitement to the delights of wading a creek, the worthy cane pole has much to offer. With one in hand you can touch base with the past, operate at minimal cost and enjoy realistic expectations of angling success.

Cane Pole Trivia

- The cane pole is a kissing cousin to the ultimate in craftsmanship when it comes to fishing, bamboo fly rods. The latter are made from carefully worked, tapered, fitted and glued sections of cane, usually featuring a hexagonal shape to the rod but occasionally using the “quad rod” (four pieces) approach. The raw material is almost always an oriental species of bamboo known as Tonkin cane (from the region of its origin).

- In many parts of the world, cane is a favorite material in construction thanks to its strength, durability and availability.

- Cane poles, with treble hooks attached to a short length of line, are sometimes used to snare white suckers and other fish during their spawning runs.

- A sturdy piece of cane makes a dandy handle for a frog gig.

- It is also possible to “fish” for bullfrogs using a cane pole. A small piece of red cloth attached to a hook and dangled before a frog resting atop a lily pad or on a pond bank will often draw a frog “strike.” Obviously, a stealthy approach is essential if one expects to feast on frog legs.

- Slender sections of switch canes were often used by Native Americans to fashion fish traps.

- Small, tightly fitted sections of hollowed-out cane, either by themselves or in combination with a turkey wing bone, make a fine turkey call. These calls are known as Jordan yelpers, after Charles L. Jordan, who popularized them circa 1900.

- Should you have the misfortune to drop a cane pole out of a boat or have a fish unexpectedly drag a set pole into the water, cane has the great virtue of floating. An old river rat from my boyhood named Al Dorsey would even throw poles in intentionally on occasions when he hooked a catfish possibly big enough to break the pole’s tip. He then followed it in his flat-bottomed boat, poled with a particularly stout length of cane, while watching for the drag of the fishing pole to bring it back to the surface. When he reckoned the fish was sufficiently tired, he would seize the pole and endeavor to land the whiskered behemoth.

Jim Casada is Sporting Classics’ Editor-at-Large and Book Columnist. This piece is a revised version of a story that originally appeared in Black Belt Bounty, a coffee-table book that he edited and for which he was a major contributor. For more information on this or his many other books, or to subscribe to his free monthly e-newsletter, visit Jim Casada Outdoors.

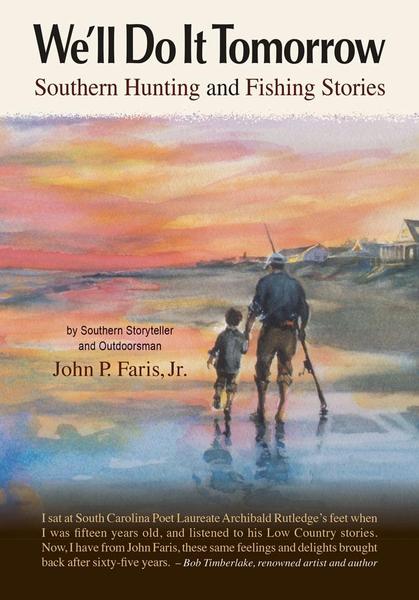

We’ll Do It Tomorrow:

We’ll Do It Tomorrow:

Southern Hunting and Fishing Stories

By John P. Faris, Jr.

253 pages, Hardcover, Signed by the author.

15 stories and 30 illustration

Reviewed & endorsed by Jim Casada of Sporting Classics who said, “This is relaxed literature on the outdoors in the vein of Babcock, Rutledge and Ruark in his ‘Old Man’ pieces.” Shop Now