An angel at home and a demon in the field, the French Brittany packs maximum ability in minimum volume.

In the 30 years or so that I’ve been scribbling about gundogs, the biggest “breed story” has been the renaissance of the cocker spaniel. Finding a decent hunting cocker in this country prior to 1980 was like finding a Parker Invincible in the attic; nowadays you can’t swing a dead cat without hitting one. And that’s all to the good, in my opinion.

What may be the second biggest breed story, though, has kind of flown beneath the radar: the establishment on these shores of the French Brittany. Or, if you want to parlez-vous Français, the Epagneul Breton. EBs, for short.

Now, if you’re thinking, “Wait a minute; isn’t calling a Brittany ‘French’ like calling an Iowan ‘American?'” Well, yes, technically. The dog known here simply as the Brittany – and recognized by the American Kennel Club as such; the surname “spaniel” was dropped in 1982 – is, indeed, a breed whose origins trace to the rugged coastal region of that same name in the west of France. Where, reputedly, its small size (conducive to quick getaways) and relatively nondescript appearance (so as not to arouse suspicion ) made it a great favorite of poachers.

Following its first importations to the United States in the 1910s and ’20s, however, the Brittany’s American fanciers took it in a very different direction. In so doing, they essentially created a similar, but recognizably separate, breed.

The American Brittany (or maybe the “Americanized” Brittany) is typically leggier and larger than its French cousins, with a longer, deeper muzzle, a broader, more domelike skull, and a longer, lower-set ear. And while only two color combinations, white-and-orange (by far the more common) and white-and- liver, are acceptable in the eyes of the AKC, the French dogs are often black or tri-colored.

In terms of performance, while versatility, ease of training and an abundance of natural ability are hallmarks of the Brittany on both sides of the pond, some American breeders have attempted to infuse more drive and “go power” into their dogs. There are at least a couple motivations for that.

One is to develop Brittanys with the pace and range to compete with pointers and setters in field trials, horseback and otherwise; the other is to equip the breed with the genetic tools it needs to hunt in places such as Texas, Oklahoma and Montana that feature the kind of vast, wide-open country the dogs’ French ancestors never had to contend with.

Ben Williams, the legendary hunter, author and Brittany breeder from Livingston, Montana, has a unique perspective on this.

“The dogs I started out with in the 1950s,” he once told me, “were essentially the original French Brittanys. They were great little dogs, but over time – and especially when I moved to Montana – I began to understand that to hunt as successfully as I wanted to, I needed a bigger, stronger, wider-ranging dog. A lot of other American breeders came to the same conclusion.”

Starting in the 1970s a handful of American sportsmen who’d hunted over EBs not only in France but in other parts of Europe began importing a few dogs to this country. It’s often said that these enthusiasts were “unhappy” or “dissatisfied” with the direction the Brittany had taken here, and there’s undoubtedly a germ of truth in that. But it’s probably more to the point to say that they simply liked what they saw in the Epagneul Breton and believed that other American bird hunters would, too.

For many of us of a certain age, our introduction to the French Brittany coincided with the launch of Gun Dog magazine in the early 1980s. David Follansbee, one of the magazine’s original columnists, was a New Yorker who shared his apartment with several EBs. As you’d expect, he wrote about them frequently, extolling their virtues as biddable, hard-working gun dogs for the “everyman” bird hunter – precisely the role the breed was originally created to play.

Brique, owned by Fred Overby, was chosen Best of Breed at the National French Brittany show.

Still, the French Brittany “movement,” if you can call it that, gained momentum slowly. It wasn’t until 1997 that the breed club, the French Brittany Gun Dog Association of America, was organized and incorporated. Since then it has been renamed “Club de l’Epagneul Breton of the United States”. One of its founders was Fred Overby, an attorney and avid hunter of both upland birds and waterfowl who splits his year between Columbus, Georgia, and Bozeman, Montana.

“It grew really quickly after that,” says Overby, who’s the past president of the club and at the moment shares his life with nine EBs.

“We worked very hard to create a dialogue and develop relations with breeders in Europe, the upshot being that between 1998-99 and 2004 there were about forty importations. Those dogs had a significant impact on our gene pool and enabled us to take a big step forward in terms of our breeding programs and the overall quality of our dogs.”

Overby’s involvement with the breed began in 1994 following a failed bid for Congress. (Seriously.) He was Sort of moping around – “Licking my wounds,” in his words – when his then-girlfriend suggested that getting a puppy and training it might be just what the doctor ordered to snap him out of his funk. He’d had pointers, setters and even Plott hounds, but the idea of a French Brittany had intrigued him for a while. His research led him to a breeder in Arkansas, John Goldsmith (no longer active), and the pup that Overby eventually obtained from him, Ellie, was everything he’d hoped for and more.

“She was a pocket rocket,” Overby reflects. “She lived to be sixteen and a half, and she pointed pretty much every upland gamebird you can hunt in North America. It didn ‘t make any difference how unfamiliar she was with the bird; in a day or two she would learn to handle it.”

Ellie’s example points up the versatility and adaptability that are among the EB’s great strengths – qualities that the breed club works hard to preserve and promote. Overby notes, too, that it’s extremely rare for a French Brittany not to be an enthusiastic natural retriever, both on land and in water.

“I’m not about to tell you they’re the equal of a Lab in the water,” he says, “but my dogs retrieve a lot of wood ducks for me. And a couple years ago one of my males retrieved a Canada goose from the Madison River in February. There were icicles on his ears when he brought it in. I was pretty proud of him for that.”

EBs typically back naturally as well, and in Overby’s estimation they occupy “the easy end of the training spectrum.” And while their reputation as relatively close workers is, in his words, “not unfair,” he emphasizes that they adjust their range to the cover and terrain and will move out surprisingly well in big, open country – the high plains of Montana, for example.

One thing EBs are not, says Overby, are good “kennel” dogs. “They need, and thrive on, attention,” he observes. “They do much better in a family environment. We like to say that the French Brittany is ‘a demon in the field, and an angel at home.'”

Another point of emphasis within the club is correct conformation, which Overby admits was somewhat lacking in the years when the EB was just gaining a toehold here. Fortunately, the standard – unlike the conformation standards of many of the sporting breeds – is all about functionality. Beauty is as beauty does, and one way to identify a French Brittany virtually at a glance is by its distinctively “cobby” body. If you’ve never heard the term “cobby,” it means something like “boxily square,” which is exactly the impression an EB with proper conformation conveys.

Bench shows and walking field trials for EBs are held by the parent club under the auspices of the United Kennel Club, which recognized the Epagneul Breton as a separate breed in 2003 and serves as its primary American registry. While some EBs are registered with the AKC as well (even some whose coat color falls outside the AKC standard, oddly enough), they’re simply lumped into the basic “Brittany” designation and accorded no special status.

Oh, and just in case you are wondering, outcrossing French Brittanys to American Brittanys is something the Club de I’Epagneul Breton of the United States strenuously discourages and explicitly frowns upon. It’s hard to imagine what purpose such an outcross would possibly serve (it’d be about like breeding a Gordon setter to an English setter), but there’s always someone, particularly in this era of “designer breeds,” who’s sure he’s hit upon the Next Big Thing.

You don’t try to fix what isn’t broken, either, and enthusiasts like Overby are awfully happy with the dogs they have.

“One of the most important figures in the history of the breed was a man named Gaston Pouchain,” he muses. “He was the president of the French Kennel Club in the mid-20th century, and a great fan of the Epagneul Breton. He came up with a famous description of the breed that translates as ‘a maximum of quality in a minimum of volume.’ We like to believe that’s as true today as it ever was.

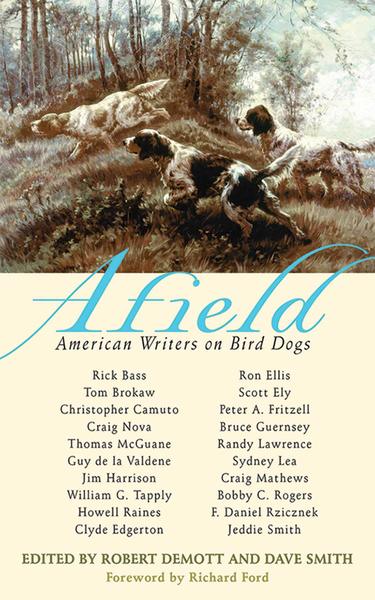

This marvelous collection features stories from some of America’s finest and most respected writers about every outdoorsman’s favorite and most loyal hunting partner: his dog. For the first time, the stories of acclaimed writers such as Richard Ford, Tom Brokaw, Howell Raines, Rick Bass, Sydney Lea, Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, Phil Caputo, and Chris Camuto, come together in one collection.

Hunters and non-hunters alike will recognize in these poignant tales the universal aspects of owning dogs: companionship, triumph, joy, forgiveness, and loss. The hunter’s outdoor spirit meets the writer’s passion for detail in these honest, fresh pieces of storytelling. Here are the days spent on the trail, shotgun in hand with Fido on point—the thrills and memories that fill the hearts of bird hunters. Here is the perfect gift for dog lovers, hunters, and bibliophiles of every makeup.

This is a delightful, handsome volume that captures the wild spirit of dogs and those who love them.This is the story of the author’s powerful connection to his family, friends and the northern outdoors. Loosely organized by the changing seasons, different sections feature essays on such topics as family fishing trips in the wilds of Maine, trophy fly fishing, turkey and deer hunting in Vermont. Buy Now