Still ruled by the spirits of Mayan kings, Mexico’s Espiritu Santo Bay is a timeless place of ancient temples, unexplored tropical forests alive with strange and wondrous creatures, and hidden lagoons where on some days, eager bonefish snatch every fly tossed their way.

Our skiff pounded south over water a dozen shades of sapphire, green and lapis — ultramarine. Off to our right, coconut palms stretched from dense Yucatecan jungle toward a morning sky where squads of frigate birds swooped, their throats a dazzle of scarlet. We were headed for Espiritu Santo Bay, wet with salt spray and too thrilled to care.

Our skiff pounded south over water a dozen shades of sapphire, green and lapis — ultramarine. Off to our right, coconut palms stretched from dense Yucatecan jungle toward a morning sky where squads of frigate birds swooped, their throats a dazzle of scarlet. We were headed for Espiritu Santo Bay, wet with salt spray and too thrilled to care.

Local fishermen spend lobster season there, where according to the Secretaria de Turismo, the stable lobster population produces 75 percent of Mexico’s commercial catch. About 150 miles south of Cancun, this barely flyfished water promised schools of bonefish which hadn’t seen a fly, much less refused one. With permit possible, and chances for small tarpon, perhaps even snook where Rio Katil divides the mangroves, we vibrated with enthusiasm.

Holy Spirit. The name of this bay seems a lot to live up to, even considering the ornate turns of the Spanish language. Plunked down in Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve (See-Awn Kah-Awn, Mayan for Birthplace of the Sky), the bay remains remote and hard to access, enough so to have escaped signs of modem incursion. No paved roads, no www dot com. Created in 1986 by presidential decree to promote rational use of natural resources while preserving ecosystems, the reserve’s 1.3 million acres harbor 325 species of birds, from hummingbirds to jabiru, the world’s largest flighted bird. Its thick tropical forest also provides refuge for such unusual creatures as bracket deer, grison and even jaguar. Loggerhead, hawksbill, leatherback and green sea turtles nest on the beaches.

We wondered if this bay could match expectations we formed years ago while working a long, jolting drive down a dusty, rutted track farther south. Then, shallow pockets and time constraints had prevented us from exploring it. Now, finally, we would delve into its reaches, catch its fish.

“We look for bone fish here,” our guide, Martin (just Martin, like certain celebrities) announced, hoisting his wooden pushpole.

A gusty March wind kept us to leeward flats, where it still managed to shudder the water like goosebumps that rise from good music. Small marine invertebrates spread their fat indigo pipes in colorless brine and trees along the shore evoked wet teabags.

“Here they come,” Bob said. Then he cast to a pair of happy young bonefish and bingo, no skunk for our boat.

The amazing thing about this fish and the rest caught and released that day? Not its sleek body, as wraithlike as its reputation, but its willingness to travel feet, yards off its prior route to gulp the proffered fly. Blustery weather that proved a bane to fellow guests may have aided in this case by blocking these bonefish from sensing us as readily. Whatever the cause (this sport fairly teems with variables), these eager bones snatched at every bug we tossed. They acted naive as newborns — we joked that we could hook up if we tied on a safety pin.

Bob grinned. “This is as good as it gets — singles and doubles coming steady, and eager to chew.”

Agreed. And for salt-suds-in-your-teeth-adventure the hour-long return voyage of smashing into and falling off waves wins the cigar. Spinal columns pounded into dust, we slogged ashore from the boat moorings to become human cargo in a stake bed truck, punchy but undefeated.

Then we all ducked palm fronds while the truck bumped over its furrowed path, our flyrods bouncing and pointing out the back. In the blink of a frond slap one rod suddenly hooked up. A feisty 30-foot palm tree took Bill, the droll Texan, well into his backing, reel fizzing, before we could alto! our driver and prompt him to back down on the sizable palm. Guides and anglers alike nearly choked with the breathless hilarity of it. In two languages. Probably shouldn’t count as a legal catch though, since Bill was, technically, trolling.

Pleased with our day, we returned to the lodge where thick towels and chef Simon Torre’s incredible pastel nuez (nut-flavored pastry) continued to freshen our humor. Our hosts, Osvaldo Balaguer and Cristina Diez, flyfishing devotees from Madrid, added to the mealtime repartee and really stretched our warped decorum — try laughing with a mouthful of gazpacho.

Pleased with our day, we returned to the lodge where thick towels and chef Simon Torre’s incredible pastel nuez (nut-flavored pastry) continued to freshen our humor. Our hosts, Osvaldo Balaguer and Cristina Diez, flyfishing devotees from Madrid, added to the mealtime repartee and really stretched our warped decorum — try laughing with a mouthful of gazpacho.

The accommodations were far more luxe than imagined — whitewashed stucco, tile and thatch, potted palms, mahogany shutters, ceiling fans. Plans to scatter additional bungalows between road and beach, where makeshift fishing palapas once stood, must obey the Preserve requirement that new structures only replace existing ones, but with considerable range allowed as to size. The main lodge, still under construction during our visit, will be outfitted with solar and wind power systems and house larger dining facilities and a rooftop mirador overlooking Santa Rosa lagoon, the Caribbean and The Ruins.

Situated about a football field west of this old fishing village, once called Santa Rosa, stand the ruins of a Late Classic Mayan temple built around 600 to 900 AD. in honor of the reclining rain god, Chac Mool (Chock Mool). A representation of Chac still rules there, recumbent in his stone chamber with its freshly thatched awning at the portal. A deep cavity carved into his chest makes room for sacrificial hearts (to supply vitality?), although his head now resides in a museum at Cozumel. Excavations have uncovered dog, and human, bones.

Next morning, we loaded back into our stakebed limo and jostled toward Sacrificio where the moored boats awaited, a shallow wade away. We passed beneath chattering green parakeets, flushed several grouse-like chachalacas, and spotted the tower of a ruina called Tupac (Too Pock) about a mile away across the maze of ankle-deep jungle waterways.

We received the same bonefish cooperation as day one, and even with a couple long-distance releases caught eight little krystal flashers. They smelled like herbal shampoo. We saw a large school of palometa and strange basaltic rocks halfway underwater that resembled petrified crocodiles. And chin chin.

“That one?” I pointed to a tree similar to our poisonwood in Florida, but with bumpier bark.

“Si, malo,” Martin replied.

“Which tree cures it?” Said to always grow near this noxious black-sapped plant is one which alleviates the suppurating blisters it causes.

“Chacha (ChawKAW) cure it,” Martin replied, and pointed to what we call gumbo limbo. This answered our question of how the ancients survived among such mean-spirited foliage.

Another day we ventured a 40-minute boat ride farther into Espiritu Santo. Other boats had seen great schools of bonefish there, with a few shots at small tarpon. We hadn’t yet, and wanted to. As flats dwellers often will, they eluded us.

But when fishing gets tough, some of the tough resort to fine Mexican beer to remove the sting. To commiserate, several of our fellow anglers sampled Scorpion Juice — a local libation produced by adding live scorpions to an empty mayonnaise jarful of tequila. By then the relentless wind had bludgeoned their plans to score high on bones, as most had relied on the conventional wisdom of 8-weight rods sufficing for bonefish. Those who had brought 9- or 10-weights for tarpon had the best edge against the breeze-on-steroids we had that week. In liquid minutes, our debate washed to its hub: Bonefishing is supposed to be hard, and by that very characteristic it appeals to those who relish a challenge. To anticipate an easy dabble in a fish bowl will generally merit you a day of frustration. If the weather doesn’t thwart you, the quirky actions of these fish often will.

But when fishing gets tough, some of the tough resort to fine Mexican beer to remove the sting. To commiserate, several of our fellow anglers sampled Scorpion Juice — a local libation produced by adding live scorpions to an empty mayonnaise jarful of tequila. By then the relentless wind had bludgeoned their plans to score high on bones, as most had relied on the conventional wisdom of 8-weight rods sufficing for bonefish. Those who had brought 9- or 10-weights for tarpon had the best edge against the breeze-on-steroids we had that week. In liquid minutes, our debate washed to its hub: Bonefishing is supposed to be hard, and by that very characteristic it appeals to those who relish a challenge. To anticipate an easy dabble in a fish bowl will generally merit you a day of frustration. If the weather doesn’t thwart you, the quirky actions of these fish often will.

On a couple forays, we squeezed our chunky lancha through narrow mangrove passages where animal calls echoed like growls from a rusted cat. This, in order to fish Santa Rosa lagoon, a large arm which extends south from Ascension Bay. Again, other boats had reported large schools of bonefish there, plus by then everyone else had fired several shots at lagoon permit. Of course, they admitted, the permit gleefully dodged all efforts to hook them, but just getting a cast at these shimmering carangids can qualify as a day-maker. Always jacks our heart-rates up to fibrillation.

In the lagoon, dozens of roseate spoonbills fluttered out of camera range, wood storks stalked nearby and one cove held so many bonefish their scent reached us long before we spied their tails. These fish defined spooky, often sprinting away before we approached casting distance — a bonefish penchant on calmer days due to their improved visual window through smoother water. Adding to our degree of difficulty, even the diminished wind in this relatively sheltered lagoon produced irritating little wavelets that inevitably slapped our boat from the noisiest possible direction.

By now the lodge will have received its new skiffs, solving the hull-slap problem which alerted those bonefish. Should greatly ease that rigorous Espiritu Santo Bay commute as well. We did manage to trick a few lagoon bones with Really Long Casts and a Gotcha variation. The permit kept us successfully at bay, although we heard that two anglers bagged grand slams — bonefish, tarpon and permit on the same day — in weeks preceding our trip. Doesn’t that figure. We began plotting to sneak the hearts out of chickens before Simon fried them for our lunch, maybe summon Chac Mool’s help.

Another day, we paddled a three-man canoe over shallow tea-colored water laced with neon-piped fish to the ruin at Tupac.

“What does tupac mean?”

“It’s a tree,” Martin replied in Spanish, although he speaks decent flyfishing English.

A temple dedicated to a tree? Heavy.

“Can you show us one?”

“Si, back there by the entrance (to this canoe trail).”

The small temple sat on a slight rise, only recently found in this maze of watery trails and overgrown pathways after being lost for ages. Countless other ruins throughout this peninsula still await discovery under the shroud of vegetation. A carved jaguar head, symbol for the world Balam and often used in names of Mayan rulers, such as Great Jaguar-Paw, king of Tikal, adorned one stone protrusion. Its (probably) matching icon across the arch was gone. A few tiny brown bats like those we had seen busy every night hung on the ceiling of an inner chamber. They rolled bright eyes when the camera flashed. We climbed a handmade wooden ladder to the tower and faced inevitable mysteries: Why Here, and especially, How, in these wetlands.

Back at the canoe dock we examined tupac trees gnarled over the pathway. Density of woodgrain in one sawed-off branch suggested ironwood, very hard, or maybe lignum vitae, both super hard and oil rich. To a civilization with little metal, either tree would carry great value. Library investigations have yet to solve the identity of the tupac riddle.

The Maya civilization appeared over 3,000 years ago and built more cities than ancient Egypt, while producing the most sophisticated written language in the Americas. Their fascinating glyphs represent either whole words or syllabic symbols that form words but look like artwork. As many as sixteen million inhabitants once spanned from southern Mexico to Honduras. They traded salt, honey, cotton, beeswax, shark’s teeth, stingray spines and shells for grinding stones, animal skins, feathers, cacao, jade, obsidian and vanilla. About 6 million Mayans remain.

Our last evening with Ozzy and Cristina, somewhere between fresh baked bolillos and chocolate eclairs (ancient Mayans cherished cocoa beans not only as a delicious food but also as money — yes, Once Upon a Time money grew on trees!), we discussed some distant flats that had proved barren, even though lush bottom grasses flourished. It aroused suspicions of illegal netting, and Ozzy had contacted the Garda Costa to pursue the issue. He told us the Garda often must get their fuel and even food from the lodge when sent on such missions. Hopes are that increased watchfulness by the Friends of Sian Ka’an and the influx of flyfishers will help curtail poaching.

Our last evening with Ozzy and Cristina, somewhere between fresh baked bolillos and chocolate eclairs (ancient Mayans cherished cocoa beans not only as a delicious food but also as money — yes, Once Upon a Time money grew on trees!), we discussed some distant flats that had proved barren, even though lush bottom grasses flourished. It aroused suspicions of illegal netting, and Ozzy had contacted the Garda Costa to pursue the issue. He told us the Garda often must get their fuel and even food from the lodge when sent on such missions. Hopes are that increased watchfulness by the Friends of Sian Ka’an and the influx of flyfishers will help curtail poaching.

Midweek a roomy Mexican Air Force helicopter had dispensed a gaggle of friends and politicos on an inspection tour, with Bruce Babbitt, Ozzy said, among them. Their tidy, blow-dried selves settled into the chopper to leave as our salt-crusted bones unloaded from the truck, so we didn’t hear their findings. We subsequently learned, however, that increased patrols to protect Espiritu Santo have kept it free of poachers since our visit.

Over coffee, we mused about the two biggest bonefish seen all week — right where our boats tie up at Sacrificio. Guarded by royal terns perched on the moorings, they had rooted happily in turtle grass until we approached, then squirted toward the reef line like dark-green bullets. Large caliber. If only we had noticed them earlier . . . How clever of them to reveal themselves at sundown of our last day. And how often we search at great length to find what awaits at our feet.

We hadn’t managed to circumnavigate Isla Chal, at the mouth of the bay with its lighthouse and coconut ranch, or search the channels of Rio Katil — our time nemesis, again. Everyone agreed that much study, exploration and charting remains ahead for Bahia Espiritu Santo, and oh, how we would love to participate. Just having that task ahead could do wonders for one’s spirits.

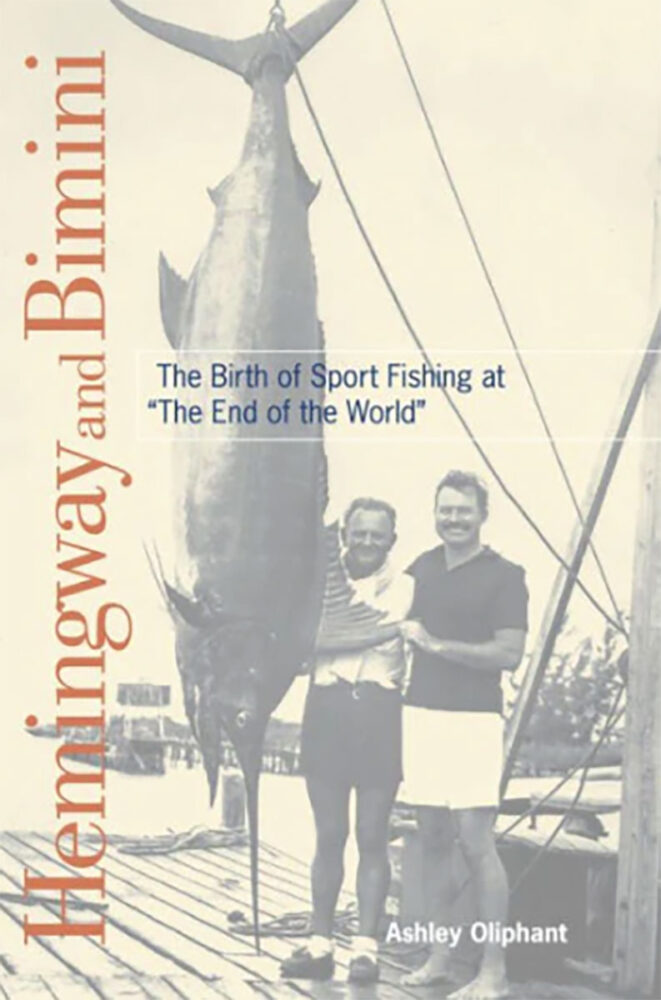

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his underappreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream. Buy Now

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his underappreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream. Buy Now