Bob Ruark left every lover of nature, every hunter and fisherman a bountiful legacy.

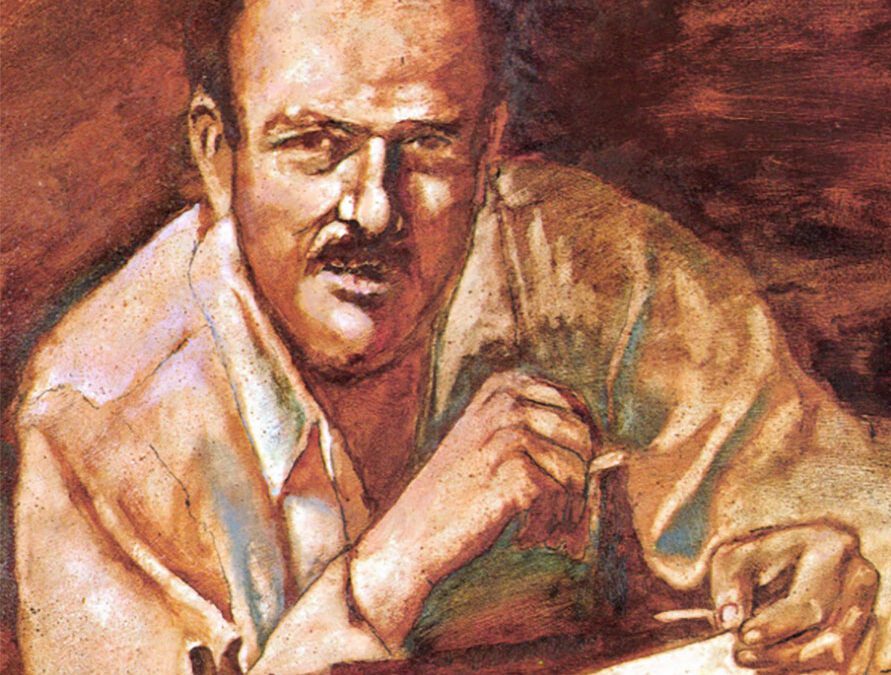

To virtually all contemporary lovers of fine sporting literature, not to mention the millions who came to know him through his biting newspaper columns or best-selling novels, the name of Robert C. Ruark is a household word. Thanks to his timeless and immensely popular series of stories in Field & Stream or The Old Man and the Boy, and a host of other articles and books treating various aspects of life in the outdoors, Ruark earned recognition as one of America’s most popular and best-loved sporting writers during the 1950s and early 1960s. These endeavors, however, were but one facet of an extraordinarily versatile and productive career that ranked Ruark as a literary figure of considerable magnitude. Yet the winsome child we follow through the joys and tribulations of adolescence and young adulthood in The Old Man and the Boy and The Old Man’s Boy Grows Older (the book-length versions of the collected Field & Stream stories) is sadly removed from Ruark the man.

Something of an enigma even in his lifetime, Ruark has, in the two decades since his untimely death in 1965, become even further shrouded in mystery. This may seem surprising, because many of his books remain popular, and while most originally appeared in large or multiple editions, they are already much in demand by collectors. Since his death, though, little save the standard obituary notices and a succinct sketch in the Dictionary of American Biography has appeared on Ruark. Likewise, aside from a couple of quite useful autobiographical pieces, there is a paucity of revealing information dating from Ruark’s lifetime in print.

Ruark was born on December 29, 1915, in Southport, North Carolina. He was the son of a Bookkeeper, Robert Chester Ruark, Sr., and Charlotte Adkins, a schoolteacher. Thanks largely to the reminiscences of the “Old Man and the Boy” stories, we know far more of Ruark’s childhood than is normally the case. Even though his family moved to the nearby, larger port city of Wilmington quite early in his life, it was in and around his birthplace that Ruark spent the most meaningful and joyous days of his youth.

Ruark with his cherished Rolls Royce in front of his “castle” in Palamos, Spain.

By all accounts his was an idyllic boyhood, and as he writes in engaging fashion in an author’s note to The Old Man and the Boy: “Anybody who reads this book is bound to realize that I had a real fine time as a boy. ‘The best and most impressionable of those good times were spent with his maternal grandfather, Captain Edward Hall Adkins, the “Old Man” of Ruark’s later writings. Adkins was an endearing figure full of dry wit, homespun philosophy, and an endless store of outdoors lore which he patiently shared with his grandson and protege — the “Boy.” While the Old Man could be vinegary at times — such as when the &y neglected the essentials of good sportsmanship or when he reluctantly found it necessary to thrash an inebriated, insolent dandy (he called such noxious characters “Willies off the Pickle &at”) who cursed him and then refused to apologize for his arrogant rudeness — at heart he was a gentle figure of great humanity. While he may have appeared a bit rough around the edges, underneath the Old Man’s scruffy exterior lay a shrewd mind and a carefully nurtured intellect-“He knows pretty well everything.”

With the guile of years of accumulated experience and a born teacher’s abilities, he imbued Ruark with a genuine love as of learning as well as endowing him with extensive practical knowledge about the outdoors. Theirs was a timeless partnership, familiar to anyone fortunate enough to have had close contact with one’s grandfather in an outdoors setting; what made it unique was Ruark’s subsequent ability to capture in prose the nostalgic wonder of those elusive days of youth. In so doing he gave us, especially in The Old Man and the Boy, enchanting pieces of sporting literature which far transcend the normal confines of the genre.

Ruark’s years with the Old Man were all too few. Captain Adkins died when the boy was only 15, but as Ruark gratefully acknowledges in the two poignant tales that conclude the first volume and open the second of the Old Man series, his death was not on opening day and “All He Left Me Was the World.” Few individuals are privileged to have such a mentor, and Ruark knew it. In the midst of the sorrow and bitter desolation that followed the Old Man’s demise, Ruark found both solace and a strong resolve for the future in the Old Man’s legacy:

It suddenly occurred to me that I was educated before I saw acollege. I made up my mind right then that someday I would learn to be a writer and write some of the stuff the Old Man had taught me. There was only one thing I had to do first, and that was to get educated and make enough money to buy back the old, yellow-painted square house (lost to creditors as a result of expenses associated with the Old Man’s final illness and the concomitant onset of the Depression) with its mockingbird in the magnolia and its pecan trees in the back yard.

A precocious youth already blessed with an ample measure of the spunk and tenacious capacity for hard work that would be among the more redeeming hallmarks of his later years, Ruark entered the University of North Carolina well short of his 16th birthday. Suddenly gone were those fleeting halcyon days spent with the Old Man and “all the honorary uncles, black and white,” who had been an integral part of the process of growing up. A much harsher world now faced Ruark, and only with the passage of time and many trials would he learn the truth inherent in Thomas Wolfe’s claim that “you can’t go home again.” Yet in one sense Ruark did go back home. He accorded readers everywhere the rare favor of sharing the Old Man with them, and in so doing here captured for those readers precious moments of their childhoods as well as his own.

At Chapel Hill Ruark soon found a niche as a collegian, a l though there are hints in his later behavior that he somehow felt that both his age and patently juvenile features inhibited his undergraduate experience from being all it should have been. A con temporary with whom he worked on the campus humor magazine later gave a fine description of the awkward but ambitious adolescent:

I think Ruark was the most guileless boy I ever knew. He was as skinny as a boat pole in those days. The biggest thing about him was his grin.

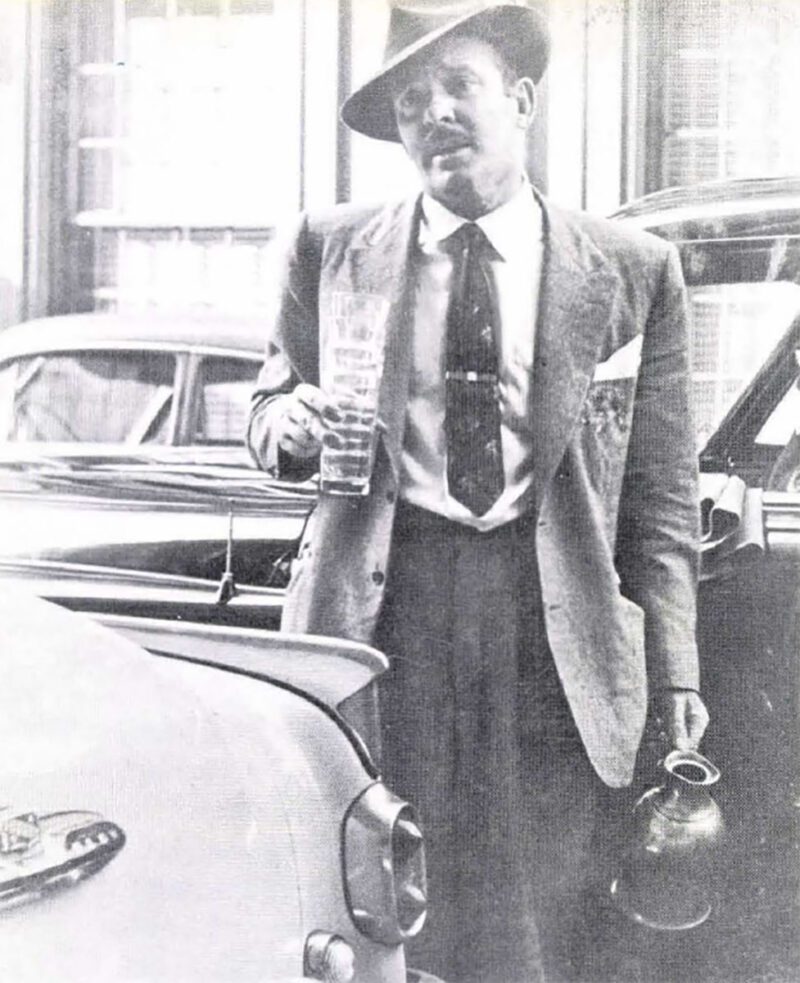

Ruark after one of his all too frequent nights on the town — in this case in Lyons, France.

Nonetheless Ruark garnered experience writing for the Yackety Yack and drawing pen and ink sketches for both the Carolina Magazine and the Buccaneer (he was an artist of considerable merit and his drawings illustrate some of his books). He even managed to scrape together enough cash, partly through a little judicious bootlegging in the dormitories and by hustling in local boarding house bordellos, not only to pay his way through college but to join Phi Kappa Sigma fraternity as well. Later, in returns to his old fraternity house, Ruark would several times reveal a somewhat unsavory side of his character. Apparently attempting to compensate for the fact that anempty purse linked with his age stood in the way of his cutting the romantic swath among the young ladies, Ruark reveled in bouts of ostentation once he had “made” it as a writer. Several photographs survive in carefully preserved albums of a now successful Ruark surrounded by a bevy of local beauties, and he took great pride in making the fraternity a gift of an ice machine. Ruark justified this unusual gift by saying that ready access to the ice for their drinks would free pledges from needless trips and thereby contribute immeasurably to their academic progress! For all his infectious love of fun, there always was a serious undercurrent deep within Ruark, and whatever his failings, he was never one to shirk hard work. A journalism major, he completed his B. A. in 1935 well towards the top of his class and immediately launched into his career.

Ruark was, in rather rapid-fire succession, a reporter and journalistic jack-of-all trades for the Hamlet (North Carolina) News-Messenger, an ordinary merchant seaman serving aboard the Sundance under a tyrannical captain, an accountant in what he styled a “fraudulent stint” with the Works Progress Administration, and on August 12, 1938, the husband of a young interior decorator, Virginia Webb. By the time of what would prove a tumultuous and rather tragic marriage, Ruark had become an employee of the Daily Newsin Washington, under the incomparable tutelage of its managing editor, Ernie Pyle. Here he rose rapidly through the ranks from copyboy to a top feature writer, with an interim as a sportswriter exposing him to the “raffish life, … astounding characters … [and] a vocabulary that never failed him when in a few years he was a highly paid columnist. ” By the time war broke out he was assistant city editor. Ruark already was, in the grudging estimation of one of his co-workers, “brash, ambitious, cocky, fast, and good.”

World War II interrupted Ruark’s meteoric rise in journalistic circles, albeit only temporarily. He entered the war as a naval ensign and later served as a gunnery officer with convoys in both the Atlantic and Mediterranean. Towards the conclusion of the conflict, he also saw shore duty in the Pacific, where an injury incurred in a jeep wreck in the Solomon Islands sidelined him. Following recuperation Ruark finished up his military service as a press censor, doubtless the capacity his superiors thought best suited to muzzling his uncanny nose for scandalous news. In the middle of the war Ruark had created a sensation, along with bringing about much-needed reforms, by writing about the shoddy treatment being accorded soldiers serving under “General Lee and a precious group of army colonels in Italy, who thought they would ape the German officer class which they had just beaten.” He also wrote several pieces for the Saturday Evening Post during this period, and by the war’s end there was little doubt about what path his career would follow.

Ruark joined the Scripps-Howard Newspaper Alliance and in short order made a major breakthrough by intentionally gaining national notoriety. Calculating how he could best make an impact as a syndicated columnist, Ruark “looked around for the biggest rock I could throw.” That rock, a veritable journalistic boulder, was a stridently sexist column on how current women’s fashions nauseated servicemen returning home. The piece, which Ruark later described as “naked sex, with a twist,” created the splash he desired. Some 2,500 letters, most from irate style-setting females, inundated the offices of the Washington Daily News. Predictably, few found any humor in Ruark’s depiction:

[They sport] nine-inch nails, wear Dolman sleeves, flat-heeled shoes, and have hair hauled up either into an Iroquois Indian top knot with a rubber band around it or else flopping in a net like a sack of mud. [Their] purple lipstick … makes them look like the wrath of God.

Roy Howard, Ruark’s boss, was suitably impressed and he gave Ruark the regular column he so desperately craved. Over the ensuing years Ruark produced upwards of 4,000 columns, totaling an estimated 2.8 million words, for the Scripps Howard syndicate. Although he would describe himself as “a pretty ordinary hack,” he wrote rapidly and well. Ruark boasted that he could turn out a daily column in a quarter hour or less and that he once wrote 16 pieces in a single sitting in Rome. As if this were not enough, he also produced over one thousand magazine articles in his career.

Once in the ascendant, Ruark’s literary star rose rapidly, and in 1947 he produced his first book, Grenadine Etching: Her Life and Loves. By this time Ruark was, according to Life magazine, the “most talked about reporter” in the country. Grenadine enhanced this reputation. Essentially a potboiler, it nonetheless showed the author at his lampooning, Iconoclastic best. A biting, rollicking satire that attacked the then commonplace sex and syrup writing of historical novels, it demonstrated Ruark’s remarkable ability to lash out effectively at anything which was sacrosanct. He would utilize the same approach, relying heavily on a facetiously ungrammatical style, in what he described as “a very unfunny sequel” entitled Grenadine’s Spawn (1953), and in both I Didn’t Know It Was Loaded (1948) and One for the Road (1949).

Although all of these books sold moderately well, Ruark, as an author, was still searching for the literary genre which would prove his true métier. Still, by the early 1950s he was something of a celebrity. He had moved to New York, was a regular at Toot Shor’s, drank free champagne at the Stork Club, lived in an expensive penthouse, dressed his wife Ginny (he always called her “Mama”) in mink, “knew everybody from Bernie Baruch to Frank Costello,” and even though his income was up to $50,000 a year, he was desperately unhappy.

Ruark was punishing his liver unmercifully through excessive drinking (a family malady, apparently his paternal grandfather, whom he styled “The Most Unforgettable Sonofabitch I Ever Knew,” drank himself to death) and he had overstepped the bounds of the fun so loved by the Old Man by searching for it too diligently. He was writing for dollars rather than posterity, and he knew he had better stuff in him. Finally summoning up enough courage to break away from his lucrative but loathsome world, Ruark fulfilled a long-cherished dream of going on an African safari.

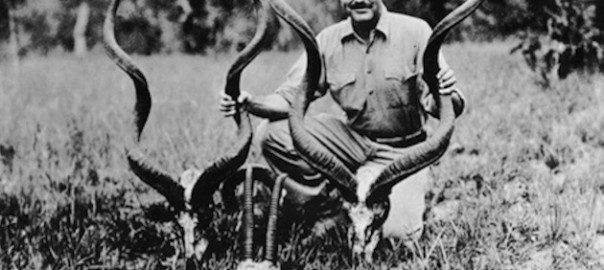

Ernest Hemingway had always been his hero, and the two were so similar in their physical features that they easily could have passed for brothers. Ruark liked being called “the poor man’s Hemingway, “and seemed to pattern Hemingway’s style in both the barroom and the boudoir. Indeed, Time magazine went so far as to suggest that ”if Ernest Hemingway [had not existed] … it [would have been] difficult to see how Robert Ruark could ever have been invented.” Determined to follow some of Hemingway’s more laudable experiences, Ruark hired the noted white hunter, Harry Selby, and set out to follow in the footsteps that had produced such masterpieces as “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and The Green Hills of Africa.

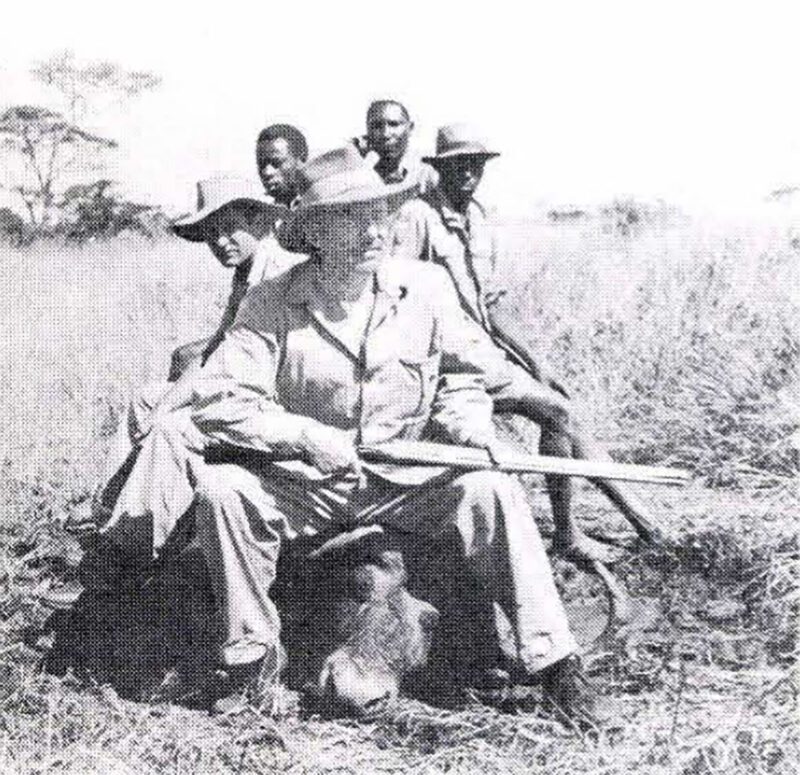

Ruark, his “white hunter,” and trackers pose with a buffalo shot while on safari.

Revitalized by his African adventures Ruark turned towards the two types of writing where he would prove truly masterful — sporting literature and epic novels founded on fact. In the former category Ruark almost immediately produced what would become far and away the best of his early books. In Horn of the Hunter (1953) Ruark introduced the Boy, jaded by years of city life, recapturing some of his marvelous childhood in a robustly racy fashion. This was his first important sporting book, and incidentally it is one that any collector would do well to acquire while it can still be found in the $30 to $50 range. While on the safari that produced this book, Ruark also had seen and sensed the seething racial conflicts, compounded by dying colonialism, which soon would result in the Mau Mau rebellion. Drawing on these experiences, he wrote the controversial and immensely successful novel, Something of Value (1955).

An instant bestseller, the book made Ruark a fortune in royalties and film rights. Something of Value was sharply criticized in many quarters for its garishness and gore. One reviewer charged that “it [was) a trip through an abattoir. The stench overwhelms the mind. Worse, it remains.” Another characterized the book as “literally horrible.” Yet Ruark, in reality, was writing uncomfortably close to the facts. As he acknowledges in his foreword:

There is much blood in this book. There is much killing. But the life of Africa was washed earlier by blood, and its ground was, and still is, fertilized by the blood of its people and its animals. This is nota pretty book, nor was it written far the pre-bedtime amusement of small children.

Not all critics lambasted the book. John Barkham of the New York Times Book Review called it “a brand new Ruark” in a “huge and frightening novel.” A Book-of-the-Month Club selection, it sold well over a million copies in various formats. The movie rights brought Ruark $300,000 from Metro Goldwyn-Mayer, a payment which the successful Hollywood version showed was amply justified. There were translations of the book in ten languages, and altogether Ruark made upwards of a million dollars from it. More importantly, the book provided him with the affluent leisure to write on subjects that would assure his lasting fame.

Financial freedom brought Ruark his finest years as a writer, but it also exacerbated a variety of personal problems. He had tired of New York’s “saloon society:”

I was getting neurotic about New York. I simply couldn’t stand it any longer. [It] was a can of worms. It was lobsters chewing on each other in a pot. It was noise, and dire, and a dead heat with disaster.

Indeed, a physical breakdown there had been one of the catalysts which engendered his African trip. He now had the opportunity to get away from the frenetic lifestyle he had never become fully accustomed to, and could write more on subjects that were to his personal liking. To this end, and one suspects, for tax reasons as well, Ruark purchased a sumptuous villa in Spain. Located in Palamos, near Barcelona, the residence was so grand that its new owner liked to call it a castle. Together with a London penthouse and anew Rolls Royce, it typified the manner in which Ruark flaunted his success. All was not idyllic however, for he continued to stowaway immense quantities of liquor, and it began to tell on his health. Still the next few years would be his most productive as a writer.

This was the period of the Old Man stories, and regular safaris in Africa, together with occasional trips even further afield, produced a steady stream of fine articles in magazines such as True, Field & Stream, Playboy, Saturday Evening Post and Life. The Old Man and the Bay appeared in book form in1957, and The Old Man’s Bay Grows Older in 1961. The individual stories had delighted Field & Stream readers, and kept subscribers’ appetites whetted for each new episode. As a collection, they are eminently readable and have an enduring appeal.

Spicy, liberally sprinkled with Ruark’s pithy language and his vivid recall of both earthy aphorisms and the salty characters who uttered them, the stories range from belly laughing jocularity to tragedy. In all of them, however, the Old Man dispenses his wit and wisdom, tinctured by doses of practical philosophy, on the outdoors and life in general. The stories were and remain a treat-fine and timeless fare to be tasted again and again. Ruark once said, “I don’t evaluate myself as a heavy thinker,” but through the medium of the Old Man he dispensed a great deal of deep thought. Sadly, Ruark himself was ignoring much of the sage advice that the Old Man had proffered.

His own life had become anything but the sublime, slow-moving existence that the Old Man not only advocated but lived. Health problems brought on by alcohol abuse continued, and by 1960, Ruark confided to a friend: “I’ve been on a strict wagon since the middle of May. . . [but] the outlook is not improved by the dismal news from London that a lifetime of sobriety awaits me.” His had become a complicated existence, yet paradoxically Ruark was happiest with its least complicated elements. As long as he was hunting, had a fly rod in his hand, or was sitting before a typewriter it was an existence of contentment and great joy.

On the surface the late 1950s and early 1960s were good times for Ruark. He was at the height of his powers as a writer, and there is no doubt that these years saw the publication of. his finest books. In addition to the two Old Man volumes, he wrote two major novels, Poor No More (1959) and Uhuru: A Novel of Africa (1962). The former was a rags-to riches saga that carried distinct autobiographical tones as well as signals that all was not right with the Boy. As one of Ruark’s friends would comment in a posthumous reminiscence, there “were signals to the world that he was no longer worshipping false gods; his trouble was that he did not know where to find any better ones.”

Uhuru contains few such personal insights, but it is a powerful book. A sequel to Something of Value, some index of its impact is provided by the fact that Ruark found himself persona non grata in Kenya. There were appreciable problems with British authorities as well, largely in connection with the contents of the English edition. The whole subject of “Uhuru”(the Swahili word for freedom or independence) was an extremely sensitive one, and the fact that Ruark managed to raise the hackles of both sides involved in the touchy issue speaks eloquently about his fictional treatment of dying colonialism in Africa.

In the midst of these years of literary triumph, a variety of developments cumulatively had the effect of creating personal disaster for Ruark. One was the death of his idol and good friend, Ernest Hemingway in 1961. That Hemingway’s career ended in tragic suicide deeply moved Ruark, and he wrote what are undoubtedly two of the finest articles remembering the man whom he called “the master.” Much closer to home was Ruark’s separation and ultimately messy divorce from his wife of two decades, a relationship which long had been a stabilizing factor in his life.

Following the break with Virginia, Ruark ended another long-term relationship. Commenting that “quite frankly after 30years in the newspaper business, I suddenly realize that I am nearing 50 and am weary of deadlines,” he gave up his work as a newspaper columnist. Perhaps this was a belated attempt to recapture some of the verve and zest for living that had characterized his earlier years. A developing affection for Marilyn Kaytor, the food editor of Look magazine, might also be viewed as part of an effort to create a “new Bob Ruark. “Whatever the case, Ruark was not to see the 50th birthday he was nearing, nor would his engagement to Kaytor culminate in marriage.

In the early summer of 1965, Ruark felt poorly for several weeks, but he continued his frenetic writing pace. In late June, however, he was flown from Spain to be placed in a London hospital. There his liver, ravaged by years of abuse, finally failed. On July 1, Ruark died from massive internal hemorrhaging. On July 10, with virtually every villager of his beloved Palamos in attendance, Ruark was buried in his adopted home. Doubtless he would have agreed with the sentiments expressed by one of his good friends: “Thank God he did not live to be impotent, old and sick like Hemingway.” Indeed, Ruark may have subconsciously sensed that his end was near. In “Long View from the Hill,” the planned but unwritten volume in a tetralogy with Something of Value and Uhuru, the book concludes with the central character, an author whose life quite closely resembles Ruark’s, dying.

Ruark once confided to a friend: “I started out to be a man… glad, sad, occasionally triumphant.” In the sense that posterity is the better for the metamorphosis that carried him from being the Boy into a far different world, Bob Ruark was triumphant. He left every lover of nature, every hunter and fisherman a bountiful legacy. We are infinitely richer for his hundreds of articles and four books (Use Enough Gun: On Hunting Big Game and Women were published posthumously) on the sporting life. Along with his novels, they constitute a lasting monument created at Ruark’s typewriter.

Critics hailed Robert Ruark’s “The Old Man and the Boy” as a tale of “infinite warmth, wisdom, and understanding.” This quiet best-seller captured the endearing relationship between a man and his grandson as they fish and hunt the lakes and woods of North Carolina. Now, the Old Man has passed on and the boy has grown up, and it’s the boy’s story that is told in this moving, nostalgic sequel. First published in the late 1950s and never out of print, “The Old Man’s Boy Grows Older” will transport you back to the days when ice cream was made at home and when fishing was not about the fish, but about the stories you told afterward. Readers young and old will appreciate and cherish this unforgettable book. Buy Now

Critics hailed Robert Ruark’s “The Old Man and the Boy” as a tale of “infinite warmth, wisdom, and understanding.” This quiet best-seller captured the endearing relationship between a man and his grandson as they fish and hunt the lakes and woods of North Carolina. Now, the Old Man has passed on and the boy has grown up, and it’s the boy’s story that is told in this moving, nostalgic sequel. First published in the late 1950s and never out of print, “The Old Man’s Boy Grows Older” will transport you back to the days when ice cream was made at home and when fishing was not about the fish, but about the stories you told afterward. Readers young and old will appreciate and cherish this unforgettable book. Buy Now