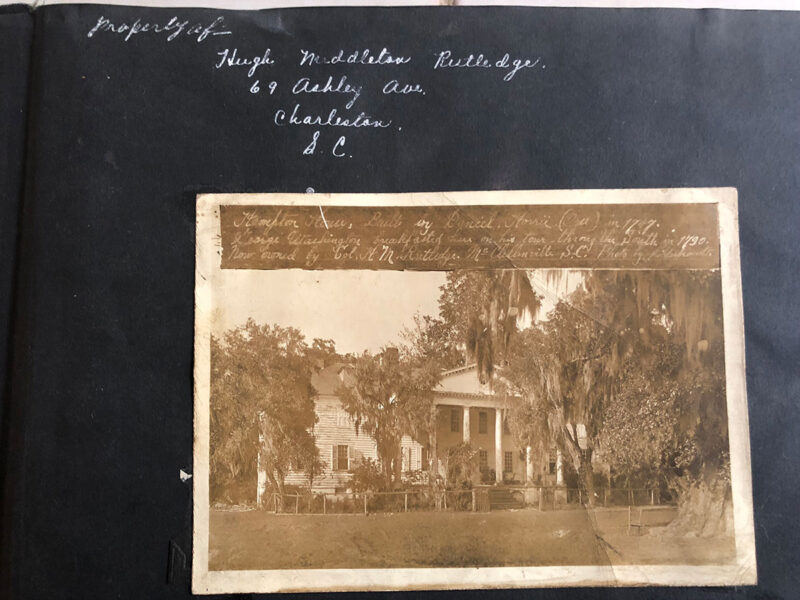

No writer has sung the South’s sporting song with the same alluring sweetness as Archibald Hamilton Rutledge. Known to family and friends as “Old Flintlock,” he was a proud son of the southern soil with roots that reached deep into the Carolina Lowcountry’s past. His ancestors included a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, member of the Continental Congress, chief justice of the Supreme Court and a South Carolina governor. During the formative years of the American Revolution, George Washington visited the plantation home where he grew up. A man seemingly born to love nature and share his experiences in the wilds, Rutledge ranks as one of America’s most popular and prolific outdoor writers. In terms of quantity and quality, no 20th century sporting scribe matched his output.

Photo of Hampton House on Plantation in Charleston, SC

Rutledge (1883-1973) was born at the family’s “Summer Place” in McClellanville, South Carolina, on October 23, 1883. If one judges from autobiographical snippets found in his books, his was an idyllic childhood, even though the wolf of poverty constantly lingered within howling distance of Hampton Plantation, the family’s ancestral home where they spent most of the year. His father, Henry Middleton Rutledge, was one of the youngest Confederate soldiers to attain the rank of colonel, and he fought through the entire war, saw extensive battlefield action, was wounded and was among those present when General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse. War experiences clearly took a toll on the senior Rutledge, and for the rest of his life he suffered from what today is known as post-traumatic stress disorder. He had minimal management skills, was incapable of handling the family’s often dire financial circumstances and basically devoted the many remaining decades of his life (he lived until 1921) to sport, wandering aimlessly about the extensive plantation grounds or daydreaming.

On the other hand, Rutledge’s mother, née Margaret Hamilton, was a strong, supremely capable lady possessing all the finest attributes of Southern womanhood. Rutledge pays moving tribute to her and his father in My Colonel and His Lady. She was the one who nurtured and molded her youngest child as a writer, guided his footsteps in a love of nature and generally shaped his career.

Rutledge’s halcyon youthful days at Hampton, which are described in delightful detail in Tom and I on the Old Plantation, ended abruptly when he reached his teenage years. When local educational opportunities, primarily in the form of tutelage from his mother, no longer met the precocious lad’s needs, he left his plantation home to enroll at Charleston’s Porter Military Academy. Four years later, although younger than his classmates, he graduated as class salutatorian. His stellar academic performance earned him medals in several subjects, most notably in the area that would become the cornerstone of his career, English. There were already signs of a writer in making. Decades later he recalled, in a sardonic mix of self-satisfaction and commentary on a life involving constant economic struggle: “It pleased me to have gathered enough gold and silver medals to survive a depression.”

His academic achievements earned him a prestigious Lorillard Scholarship to attend Union College in New York, but for a sheltered, “countrified” son of the South, this period far from home must have been exceedingly trying. The family lacked sufficient funds for him to return home during holidays or the summers, so he was in effect exiled throughout his college years. He later experienced a similar situation when he took a teaching position at Pennsylvania’s Mercersburg Academy, although at least then he could return to Hampton each Christmas.

Still, Rutledge weathered constant homesickness while fostering an admirable work ethic that hallmarked his entire adult life. He graduated from Union with honors in 1904, having somehow found time to star on the school’s track team, become a polished orator and debater and participate in numerous extracurricular activities. Each summer he worked for Charles Steinmetz, the head of General Electric whom Rutledge described as an “elemental genius.” Through him he met famous individuals such as Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, George Westinghouse and John Burroughs. The last was perhaps the greatest nature writer of his day, wonderfully gifted when it came to communicating the outdoor world’s glories. He made a deep impression on the young student and decades later, when Rutledge won the coveted John Burroughs Medal for natural history writing, he must have looked back to the glad occasion of their first meeting with warm reflection.

Not long after graduation, still shy of his 21st birthday, Rutledge accepted a supposedly interim position teaching English at Pennsylvania’s Mercersburg Academy. When the headmaster’s wife first saw the young man, she unthinkingly blurted out: “He will never do—he’s too young.” Her words proved singularly inaccurate. Rutledge taught at Mercersburg for the next 33 years, becoming a revered figure among students. Within three years he was married to Florence Louise Hart, the younger sister of the woman who had greeted him with such skepticism.

Hampton House

The Mercersburg years were busy, bustling and at least for a couple of decades joyous ones. Three sons were born to Archibald and Florence, and the couple became beloved Mercersburg icons. Many of the Hampton Plantation bucks he killed over the years fell to a Parker double barrel given to him by admiring students. Each year the family returned to the hallowed grounds of Hampton for Christmas, and from the time of his parents’ deaths in the 1920s, those annual visits strengthened his dream of the day when he could once more truly call the plantation home.

Meanwhile, desperately needing money for his family and Hampton, he wrote constantly. Eventually his poems and magazine articles numbered in the thousands, and in collected form they constitute the basis for all but a handful of his dozens of books. Gradually his literary efforts earned him renown and a wide following. By the early 1920s he was a nationally recognized writer on natural history, sport and the South’s way of life.

Already the recipient of numerous honors and awards, a major watershed in Rutledge’s career came in 1934 when he was named as South Carolina’s first poet laureate. This enabled him to begin thinking seriously about a permanent move back to the Palmetto State to undertake the massive project of restoring Hampton Plantation to its one-time glory. Several factors pushed him in this direction. His wife died unexpectedly in 1934, and the woman he would subsequently marry as his second wife, Alice Lucas, had been a childhood sweetheart. His sons were grown, thus easing one major financial burden, and in a first-ever action, Mercersburg Academy agreed to give him a small retirement stipend. That income, along without another modest amount coming from his service as South Carolina Poet Laureate and money garnered from his writings and book royalties, convinced him to return to Hampton permanently. It was a daring move, especially considering the country was in the depths of the Great Depression, but it opened a new and lengthy chapter in his life.

Those years, from the move back to Hampton in 1937 until his death in 1973, were filled with an overflowing cup of bittersweetness blending gladness and sadness. Prince Alston, his beloved “hunterman” and “a companion to my heart,” had died. So had many of the other blacks who figured so prominently in his hunting stories. To him, they had been part of an extended and cherished plantation family who opened up before him “the pages of nature’s gigantic green book” and provided “to my heart a peace the world could not give.”

Photo of Rutledge and crew hunting on Hampton Plantation, circa 1929

Other cherished aspects of earlier years also faded, most notably the glories of the annual Hampton Hunt in the Yuletide season. For “a period of twenty shining years,” as Rutledge’s youngest son, Irvine, described it, the weeks spent hunting while celebrating Christmas dominated life on the plantation. That came to an abrupt end in 1943 when his middle son, Middleton, was killed in a traffic accident. He was a physician, part of the trio of sons Old Flintlock described as a “doctor, a lawyer (Irvine) and an Indian chief (Archibald, Jr.). As the latter description correctly suggests, Arch returned from service overseas in World War II to become a perpetual problem child. He fell victim to chronic alcoholism, could not hold a job, and presented alarming challenges for his father. Additionally, Old Flintlock’s second marriage proved less than happy, while unending economic stress connected with Hampton’s restoration merely added to his heavy burden.

To Rutledge’s enduring credit, he persevered through it all. Prone to accidents, he suffered all sorts of falls and broken limbs. In later years he was bedridden quite a bit. Thankfully Arch, Jr.’s widow, Eleanor, helped him manage Hampton, and there were always bright spots to lift his spirits. He found constant refuge in hours spent writing. A powerful speaker in great demand for commencement addresses and similar special occasions, he delighted in addressing youthful audiences and doubtless this helped keep him young. When at Hampton (his second wife detested the place, which for many years lacked electricity and other modern conveniences, and she pretty much refused to leave their second home in Spartanburg, South Carolina) he welcomed visitors, pilgrims drawn by his writing and lyrical descriptions of the place in Home By the River; greeted busloads of school children with great enthusiasm; and all the while oversaw improvements to the home and its sweeping grounds. He personally planted untold hundreds of azaleas and camellias he had rooted or grown, and the daily mail brought welcome letters from legions of admirers.

Most of all though, he found refuge and solace for his soul in writing. For a span of more than six decades, poems and stories, along with a few stand-alone books, poured from his prolific pen in a steady stream. Most of his finest hunting tales first appeared in magazines and were then collected in books. On the other hand, works of an inspirational nature, together with books focusing on those he knew best—his parents and the African-Americans at Hampton—were primarily original efforts.

As for outdoor-themed material, with hunting and nature writing sharing top billing, beginning with Old Plantation Days and Plantation Game Trails in the early 1920s and continuing in a steady stream for a half century through the publication of The Woods and Wild Things I Remember in 1970, Rutledge wrote more than a dozen major books of enduring value. Probably the best-known and possibly the best of them is An American Hunter, but Hunter’s Choice, Those Were the Days and Tom and I on the Old Plantation are all truly exceptional.

“Miss Seduction”

Yet merely listing the titles of major books or noting that Rutledge received honorary degrees, gold medals and other recognitions in bountiful fashion fails to provide a real measure of the man and his irresistible way with words. Ever the Southern gentleman in person, he was equally adept at inveigling readers with his prose. When he suggests that “some men are mere hunters; others are turkey hunters,” anyone who has become hopelessly addicted to the quest for America’s big game bird readily understands what Old Flintlock means. He had a marvelous knack of conveying the delicious unpredictability and unexpected delights of turkey hunting. When well into his 60s he wrote: “Turkey hunting has been with me a kind of religion since a hatchet was a hammer; and perhaps I have learned a little of the art. Yet even after a half-century of hunting the noblest game bird that graces America’s wild, I am going to confess that I am still in the kindergarten.”

In a similar vein, he was astute enough to realize that the use of various types of turkey calls (and he made and marketed a box he styled “Miss Seduction”) “is a thing to be learned rather than told of” even as he humorously noted that “a man is as likely to be able to call a scared wild gobbler as he is to make a hole-in-one for nine straight holes.” Or, as he addressed the turkey’s inherent wariness from another perspective: “You may hear of men who have stalked wild turkey; and perhaps the thing can be done—if the turkey is blind.” He readily understood that “a real turkey hunter follows his sport as if it were a religious rite; he is a man of infinite caution, woodcraft and patience. He is a consecrated, a dedicated man; admirable, too, in the sense that his virtues are those the pioneers had.”

For all that he waxed eloquent on wild turkeys, writing at least a hundred major magazine pieces on the subject, the sport for which he is best known and about which he wrote the most was deer hunting with dogs. “With me deer hunting is kind of a religion,” he wrote, “and I have worshipped at this shrine ever since a grown oak was an acorn.” He hunted whitetails for almost eighty years and wrote about them throughout his adulthood. He also spent untold hours observing them, and on full moon nights Rutledge often nestled on a platform in one of Hampton’s massive oaks to observe their behavior in the gloaming. In 1952, two decades before his death, his meticulously maintained records showed he had “observed, in their native haunts, under almost all conceivable circumstances, more than 8,000 wild deer.”

Old Flintlock with a gobbler at foot of Hampton House steps.

From the time he was still in the cradle and his mother discovered him clinging to the antlers of a tame buck that roamed the plantation grounds until he was on his death bed holding the rack of the finest whitetail he ever killed, Rutledge was enchanted by “that noble, elusive, crafty, wonderful denizen of the wilds.” Through his words he shared his enchantment not only with deer and turkeys, but hunting dogs and frightening denizens of Lowcountry swamps, animal behavior and natural history, with legions of admirers.

He also left posterity with penetrating thoughts sure to give any thinking outdoorsman reason aplenty to pause and ponder. Nowhere was that more evident than in what must rank as one of the finest expressions of the hunting ethos ever, his essay “Why I Taught My Boys to Be Hunters.” Rutledge’s philosophy on hunting was straightforward and eminently sensible. “If a man brings up his sons to be hunters, they will never grow away from him. Rather the passing years will only bring them closer, with a thousand happy memories of the woods and fields.” Then, warming to his theme, he continued: “It is my fixed conviction that if a parent can give his children a passionate and wholesome devotion to the outdoors, the fact that he cannot leave each of them a fortune does not really matter so much. They will always enjoy life in its nobler aspects without money and without price. They will worship the Creator in his mighty works. And because they know and love the natural world, they will always feel at home in the wide, sweet habitations of the Ancient Mother.”

Those are words of penetrating power; thoughts to be absorbed and assimilated. They offer but one of countless examples of the reason why Rutledge should be remembered not only as the sage of the Santee River, but as an icon of American sporting letters whose wisdom is as enduring as it is endearing.

This volume is the first in a trilogy which will once again make available Rutledge’s finest prose work. Casada, a long-time student and admirer of Rutledge, has chosen thirty-five stories which represent Rutledge at his best. To enter the world of this masterful storyteller is to share the pleasure he brought to legions of admiring readers during his lifetime. Buy Now

This volume is the first in a trilogy which will once again make available Rutledge’s finest prose work. Casada, a long-time student and admirer of Rutledge, has chosen thirty-five stories which represent Rutledge at his best. To enter the world of this masterful storyteller is to share the pleasure he brought to legions of admiring readers during his lifetime. Buy Now