As I watched, my resentment began to leave and I knew that, whatever the reason for his coming in, it must have been very important.

While casting the long riffle below the pool, I became aware that I was not alone, that someone was there on the river with me. It wasn’t that I actually heard anything, just a vague realization. I stopped and listened, but could hear nothing — only the plaintive calling of a whitethroat and the gurgling of the current beneath the alders.

While casting the long riffle below the pool, I became aware that I was not alone, that someone was there on the river with me. It wasn’t that I actually heard anything, just a vague realization. I stopped and listened, but could hear nothing — only the plaintive calling of a whitethroat and the gurgling of the current beneath the alders.

I began to cast again and hooked a 10-incher from behind a boulder in midstream. Then I heard the soft unmistakable swish of a rod. It came from upstream, at the head of the big pool. There was no doubt now: swish- swish – swish, the sound of a man getting out his line. I waded out of the river and moved up toward the sound, and suddenly the joy of the morning was gone.

For years I had been coming to the headwaters of the Manitou over as rough and rugged a trail as there is along the North Shore of Lake Superior, windfalls and tangled jungles of hazel brush, rocks and muskeg, black flies and mosquitoes. But because the river was mine alone when I got there, it had always been worth the effort. But now the sparkle was gone. I knew I was selfish to feel as I did about the Manitou. It was not mine any more than anyone else’s, but I had always felt a certain kind of ownership there based on the fact that I had earned the right to enjoy it.

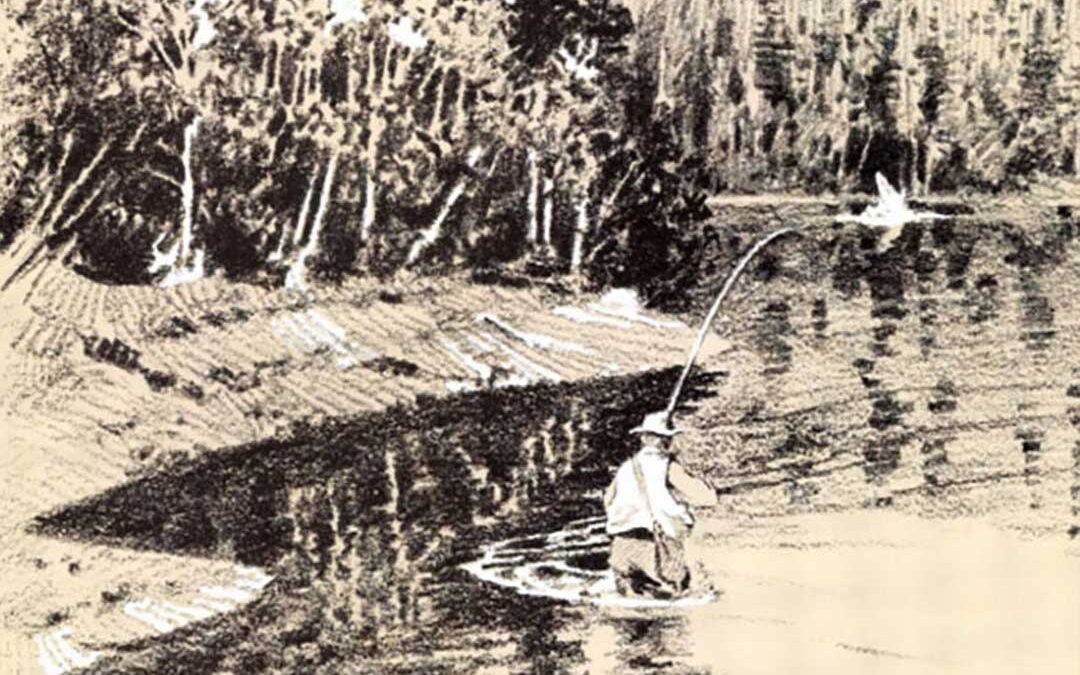

I climbed a little knoll above the big pool where I could watch without being detected. A stranger was casting a rise toward the far end. He was a small man, a spare little figure standing knee deep exactly where I used to stand at the point where the upstream riffle enters the pool. He was working the bank as though he had been there many times before and knew where to place his fly. His legs were braced and he made each cast as if afraid the force of it might throw him off balance. He was old, I could see that, far too old to be fighting fast, treacherous waters and slippery boulders of the Manitou. I saw him take a little trout and tremble with the effort of landing it, then a larger one. He waded cautiously back toward the shallows, slipped and almost fell when he stooped to use his net.

As yet he had not seen me, and I had made no sound. A trout was rising again in the far end of the pool and he was trying hard to reach it. And then I began to wonder how he had come in and what it must have taken for the old man to negotiate that long trail.

As I watched, my resentment began to leave and I knew that, whatever the reason for his coming in, it must have been very important. Far better to share the river with someone who felt as I did, and I began to look with a certain approval at the way he blended into his background, at his weather-beaten coat, the ancient, patched-up creel, the torn hat band with its fringe of flies. He was part of the rocks and trees and the music of running water.

He was casting carefully once more, and so absorbed was he that he never once looked up toward where I stood. The fine leader soared above the pool and each time it unfurled a trout at the far end would break water and slap the fly with its tail. For a few moments he studied the surface, then reached down and picked up a fly eddying near him. After examining it intently, he thumbed slowly through his book. Selecting a new fly, he tied it on and began casting once more. This time the trout arched above it and the old man struck. The fish was on — not a large one, but he played it as carefully as though it weighed three pounds. Never wasting a motion, he anticipated every rush. At last, the trout circled slowly at his feet. As he reached with his net, he looked up and saw me.

There was no surprise, just a smile and a nod as though he had known I was there all the time. There were fine wrinkles at the corners of his eyes, and in them was the happy look of a man who was doing something he wanted to do more than anything else in the world. Wading slowly out of the stream, he came over to where I sat.

“Hello,” he said, breathing hard. “You know the Manitou, too.”

“Been here many times,” I answered. “Nice trout in that pool.”

He opened up his creel and showed me the three he had just taken, turning them over so I could see the flame along the undersides, the crimson spots and the mottling of brown and green.

“Pretty,” he said. “Worth hiking in here just to see them again.”

He took off the old creel. It was laced with rawhide where the willow withes were pulling apart, was dark as willow gets through many years of use. He placed it in the shade of a mossy boulder just above the water, hung his net in a bush alongside and stood his rod against a tree. Then he sat down on the bank beside me.

“Today is my birthday,” he volunteered. “Eighty years old, and this little trip is a sort of celebration. Used to make it every year in the old days, but now it’s been a long time since I came in.” He pulled out his pipe, tamped it full of tobacco, drew long and luxuriously as he settled back against a pine stump.

“Had to see the old river once more, take a crack at the old pool. Came in here the first time when I was cruising timber for one of the outfits along the North Shore. You should have seen the river then, all big pine and the water so dark you couldn’t see the bottom anywhere. Trout in here then, big ones, three- and four-pounders lying in all the pools and the rapids fairly alive with their jumping.”

“Still some nice ones if you hit it right,” I said. “Always a big one waiting in the deep end of the big pool, and when there is a hatch on, most anything can happen.”

“Yes, I know,” he answered, “and the river is still mighty pretty, but mostly I wanted to come in here just to remember.”

A trout was rising again, a good one and the ripples circled grandly until they hit the bank.

“Just before dusk he’ll take a gray hackle, perhaps a gray with a yellow body.”

But the old man wasn’t listening, nor was he watching the rise. He was seeing the river as it used to be.

“Where we’re sitting right now, there was a stand of pine four feet through at the butt, so thick you could barely see the sky through the tops. No brush then, not a bit of popple or hazel except in the gullies, no windfalls or blackberries either — just a smooth brown carpet of needles as far as you could see. Could drive a two-horse team anywhere through these woods.”

His face was alight with his memories, and his blue eyes looked past me down the river, took in the pool, the riffles below and a whole series of little pools for a mile downstream. I followed his gaze and for a moment it seemed as though I had never seen the Manitou before. The old stumps blackened and broken by fire and decay became great pines, and the brush-choked banks were clean and deep with centuries of duff. The water before us disappeared in perennial shadows and the stream was full to overflowing once more. Rocks that now protruded were hidden beneath the surface, and from their tops floated long streams of waving moss. The water eddied and swirled around them, and trout lay in their wakes waiting for a fly.

Then while I watched, the vision seemed to fade and I saw again the poplar covered banks, the bright sunlight on the water and the old man dozing quietly beside me. He must have heard me stir, for he opened his eyes wide, smiled and rose painfully to his feet.

“Must have been dreaming a bit,” he said. “I’ve a feeling there’s another big one waiting in that pool. Better work in there, son, and take him.”

I told him that I had a partner waiting for me downstream and that I’d have to hurry or I’d miss him. As I started to leave, he strapped on his battle-worn creel and picked his way once more down to the water’s edge.

“Happy birthday!” I yelled.

He waved his rod in salute, and I left him there casting quietly, hiked clear around the pool so I wouldn’t spoil his chances with the big one at the far end. The whitethroats were singing again and high up in the sky the nighthawks were beginning to zoom. There was no wind — a perfect night for a May-fly hatch on the big pool.