On Christmas Day in 1941, millions tuned their radios to Kraft Music Hall, NBC’s hit variety program hosted by Bing Crosby, one of Hollywood’s brightest stars and the best-selling recording artist of the 20th century. Bing was in the middle of filming Holiday Inn with Fred Astaire. Irving Berlin had composed the film’s music and was keen to include a song he’d originally written for Astaire to sing to Ginger Rogers in the 1935 musical, Top Hat.

“I don’t think we have any problems with that one, Irving,” Bing said after Berlin played it for him.

It was an unlikely song for a Russian Jewish immigrant to compose: wistful, with none of the merriment of the season. But when Crosby decided to sing “White Christmas” for the very first time on that Christmas Day broadcast, it couldn’t have been more “right”—or so desperately needed. The Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor 18 days before, catapulting America into World War II. May your days be merry and bright, and may all your Christmases be white gave hope and comfort to an emotionally shattered nation.

“A cleft palate could have sung it successfully,” Bing remarked.

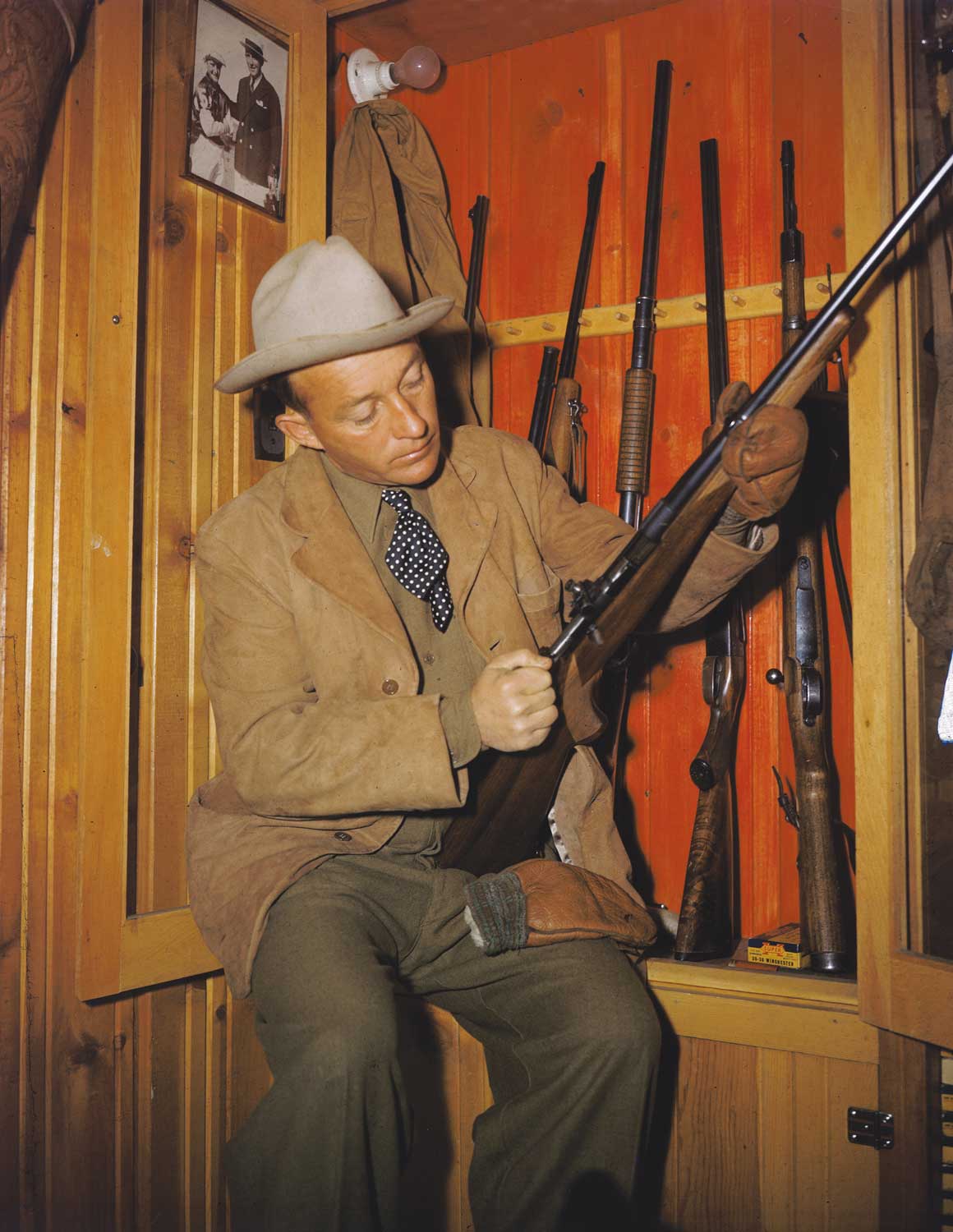

Crosby singing “White Christmas” remains the best-selling record of all time and how he is best remembered—just one of many unparalleled achievements this modest, affable, outwardly easy-going man realized in his lifetime (see sidebar). To temper the intensity of his professional—and an oftentimes conflicted personal—life, Bing frequently headed for the woods and water. Hunting and fishing were lifelong passions for Crosby, with the crooner shouldering a gun and casting a line as he grew up.

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

His father was Harry Lincoln Crosby, a descendant of Mayflower passenger William Brewster, the religious elder of the Mayflower Colony in America. His mother was Catherine Helene Harrigan, a second-generation Irish-American. The fourth of seven children, Bing Crosby was born in Tacoma, Washington, on May 3, 1903, but grew up in Spokane, where his family moved into a house his father built when Bing was 3. His nickname was bestowed on him in grade school by classmate Valentine Hobart, who said he looked like “Bingo,” a character with pear-shaped, protruding ears in the comic strip “Bingville Bugle,” published in the Sunday edition of the Spokane Spokesman Review.

Bing’s skill with a gun and rod, good sportsmanship, and deep-seated respect for wild things and their environment is well-chronicled in the many shows he filmed (always gratis) for The American Sportsman and the memories treasured by those he spent time with afield. Maybe the love and passion he poured into his work equaled, or even exceeded, his love of the great outdoors. But one thing’s for sure: No public figure since Theodore Roosevelt has done more to promote wildlife conservation and responsible hunting and fishing practices in America—and around the world—than Harry Lillis “Bing” Crosby, Jr.

A Lifelong Hunter and Fisherman

“You know,” Bing said in one of several Ducks Unlimited campaigns he appeared in during the late ’60s and ’70s, “the first pioneers wrote the folks back home that, out here, the flocks of ducks and geese were so big they darkened the sun. Maybe they were . . . for a while. But you know, soon North America started filling up with people. For a while nobody paid too much attention to the situation, till the ’30s, then a survey was made, and it proved that the ducks were declining. Yes, they were declining very rapidly, indeed, and the reason was that the breeding marshes were drying up. Well, this worried a lot of folks. Soon these worried folks got together and they organized Ducks Unlimited. Since that time this international conservation organization has been spending millions—sort of a colossal home-improvement program for ducks and for geese.

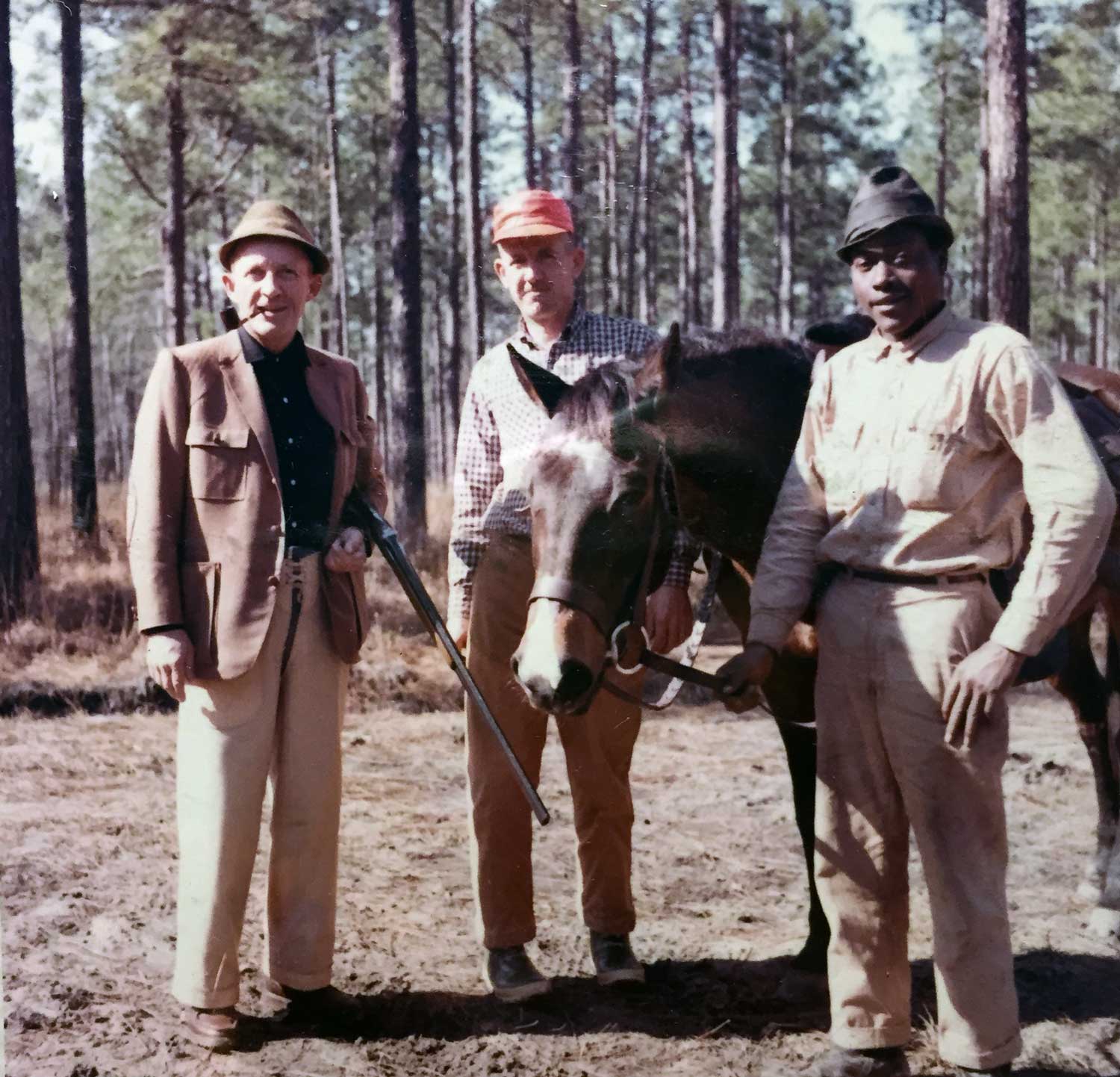

Bing Crosby on a quail hunt at Medway Plantation in 1966. Image courtesy College of Charleston.

“So the next cold, blowy winter’s day, when you’re sitting by the fire, sort of wrapping yourself in a nice hot buttered rum, you give a thought to those poor DU guys. DU is doing things that have to be done if you want to keep the flyways busy when our sons and grandsons are taking our place in the blinds.

“Well, we still get bad years and good years, but as time goes on the bad years aren’t so bad and the good years get better—partly because people are supporting DU projects. I guess it really takes society a few generations to cotton to the idea of conservation, but if you let it go now, it’s ‘Goodbye, Charlie.’ It’s the old story: You have to pay the piper if you want to hear the song. And if you’ve ever been out in the duck blind—at dawn, you know, with your fingers freezing, your ears straining—man, it’s an awful pretty song.”

Bing imbued the role of the conservationist and good sportsman in 16 consecutive seasons of The American Sportsman—his last, filmed hunting in Tasmania for sand grouse six months before his death in 1977. Host Curt Gowdy said his happiest shows were filmed with Bing and Phil Harris, a longtime hunting buddy.

“They were fun guys and good outdoorsmen. I did six or seven shows with them,” Gowdy said in an interview published in the New York Times commemorating the 20th anniversary of the preeminent outdoor television series. “Harris was an excellent wingshot. Some years ago we did a pheasant-hunting show in Nebraska, and he showed up with a 28-gauge Winchester pump. He loved that little gun, and when our Nebraska host saw it, he said, ‘Mr. Harris, I’m not being smart, but these Nebraska pheasants are big and tough, and you can’t bring them down with that little thing.’ He was wrong.”

Grits Gresham, co-host and a producer of The American Sportsman for 13 years, echoed the same sentiment when he and his son, Tom Gresham, host of Gun Talk Radio and Gun Venture TV, joined me in 2006 for a week of pheasant and grouse shooting in Scotland. It would be Grits’ last bird-hunting trip, but happily, it was captured on film for Dez Young’s Wingshooter’s Journal (available on DVD on Amazon.com).

“Bing really was an excellent shot and a great sport,” Grits grinned from one mutton-chop sideburn to the other under the brim of his trademark cowboy hat. “But Phil never missed.”

An All-around Sportsman

From the time he played second base at Gonzaga University (“I was a good fielder but a poor hitter”), sports were a big part of Bing’s life. Best associated with golf, he earned money in high school as a golf caddy. Finding he was pretty good with a golf club, he quickly developed a real love for the game. In 1937, while riding the wave of his success in Hollywood, he realized how little money professional golfers made. So he partnered his celebrity golfing buddies with professional golfers and created the Bing Crosby National Pro-Am Tournament, affectionately called the “Crosby Clambake.” Rechristened in 1985 as the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am Golf Tournament, it is one of the oldest tournaments on the PGA circuit and continues to raise millions of dollars for charity.

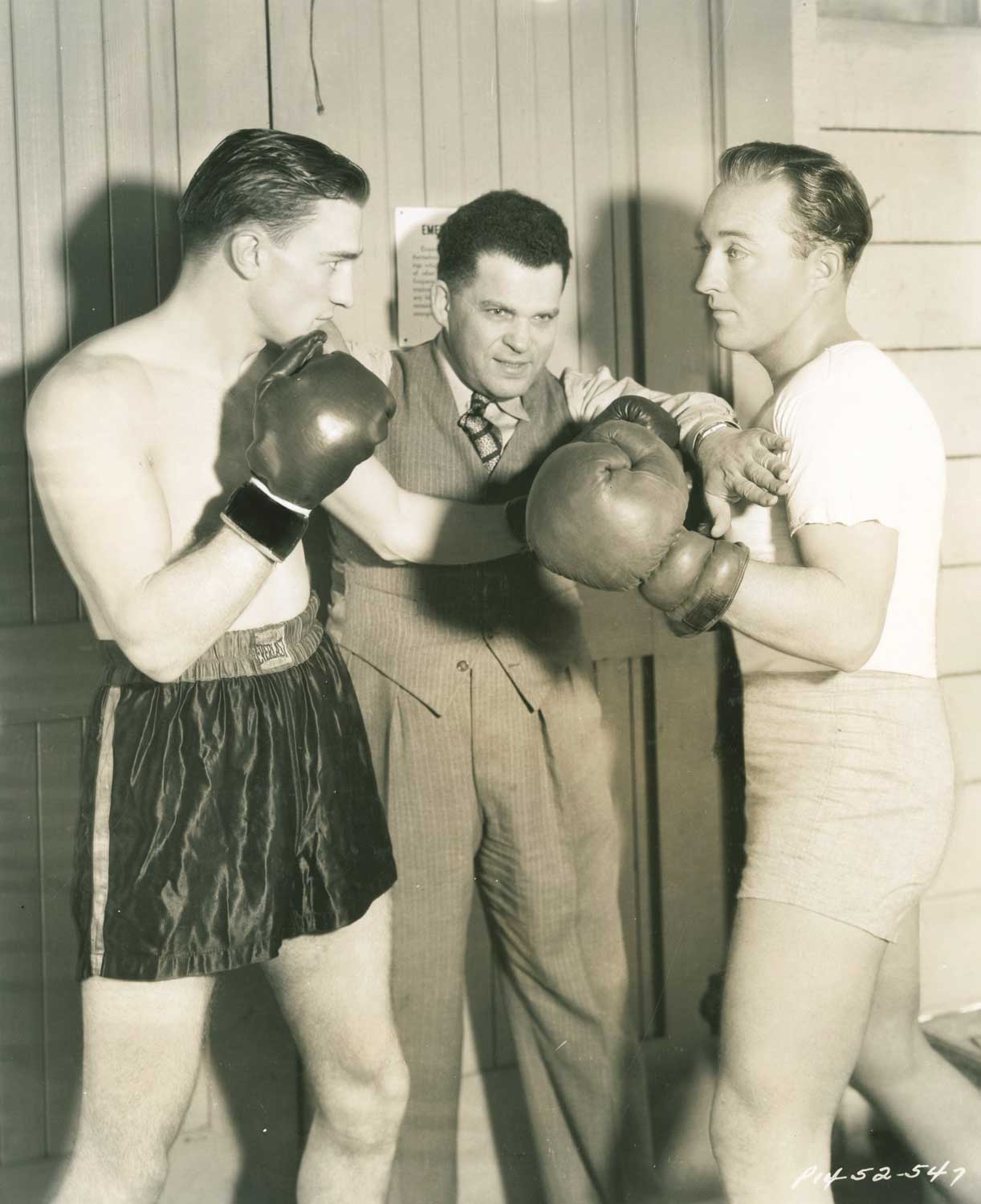

Bing Crosby and Freddie Steele mock-spar for a publicity photo in 1936.

Image courtesy heritage auctions/www.ha.com

Bing made history again in the early ’70s when he fought with the PGA to allow women to play—among the players on the distaff side, his second wife, actress Kathryn Grant Crosby, mother of the three youngest of his seven children. (Bing’s youngest child, investment banker Nathaniel Crosby, was low amateur in the 1982 U.S. Open and winner of the Porter Cup that same year.)

Bing also had a passion for fast horses. A few months after the first Crosby Clambake, he and some friends—actors Pat O’Brien and Gary Cooper, comedic stars Joe E. Brown and Oliver Hardy (of Laurel & Hardy fame), and businessman Charles S. Howard (owner of Seabiscuit, the greatest thoroughbred race horse of all time)—formed the Del Mar Racing Association. They pooled their resources to build the Del Mar Racetrack, a thoroughbred racing track 20 miles north of San Diego, and Crosby wrote and recorded “Where the Turf Meets the Surf” as its theme song.

On August 12, 1938, Bing stood at the front gate to personally welcome a record crowd that gathered to watch his colt, Ligaroti, challenge “the people’s champion,” Seabiscuit, ridden by Canadian-born jockey, George “The Iceman” Woolf in a one-on-one, $25,000 winner-take-all race. In an amazing rivalry, Lindsay Howard, son of Seabiscuit’s owner, Charles Howard, rode Ligaroti. Broadcast on NBC Radio, the crowd went wild as Seabiscuit won by barely a nose in one of the most incredible finishes in the history of horseracing.

In 1946 Bing purchased a stake in the Pittsburgh Pirates, providing comedic fodder for his friendly rivalry with Bob Hope, his friend and co-star in seven hilarious “Road To” pictures. Hope, a part-owner of the Cleveland Indians, which won the 1948 World Series, slung barbs at Bing for a dozen years until the Pirates took the pendant in 1960.

Hearing of Bing’s death earlier on the day of the start of Game Three of the 1977 World Series in Los Angeles, the opening pitch was briefly delayed when Major League Baseball honored one of its most devoted fans with a moment of silence. Bing’s support of baseball extended beyond the major leagues: the Bing Crosby Stadium in Front Royal, Virginia, honors its namesake for the important contribution he made in the building of a new ballpark for the youth of that community.

A Big Part of a Life Lived Large

Between 1971 and 1974, Bing’s schedule was filled with back-to-back appearances on television, including his annual Christmas show, time spent in the recording studio, appearances at various benefits, traveling with his family, and, of course, hosting the annual Crosby Pro-Am Tournament and playing golf himself, both at home and abroad. But in those few years he consistently broke away to replenish his soul with the peace and fulfillment he derived from hunting and fishing. Following are some sporting highlights from those years:

In 1971 Bing had flown to Iceland to fish for salmon and tape a show for The American Sportsman the previous April. In January, at a gala dinner at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel honoring Bing’s conservation efforts by the Committee for Atlantic Salmon Emergency, a Danish film distributor announced Crosby’s films will ceased to be shown in Denmark in defiance of Crosby’s support of the Committee’s platform. Bing dismissed the incident.

In March, he took a photographic safari to Kenya to observe wildlife conservation for a segment of The American Sportsman. He returned to California in time to head down to Las Cruces for a month of fishing. June found him fishing in Seven Islands, northern Quebec, where he caught a 17-pound salmon. In August, he was grouse shooting in Scotland.

In January 1972 Phil Harris and Grits Gresham joined Bing in Mexico for whitewing shooting, and the following month, and again in April and May, he returned to Las Cruces to fish. He retired his fishing yacht, True Love, named after the song he sang to Grace Kelly, his friend and co-star in two films, with a new, 38-foot Chris Craft he christened the Dorado. In July, he and his only daughter, Mary Frances, flew to Kenya, where she shot a 12-foot killer crocodile on the Tana River.

In February 1973 Bing and hunting buddy, Phil Harris, set out to hunt pheasant in Iowa. In May he was back at Las Cruces to fish and celebrate his birthday. He headed north in June to Alaska to fish and in September, attended a Ducks Unlimited event to speak about waterfowl conservation.

The year 1974 started poorly. On New Year’s Day Bing was admitted into the hospital with pleurisy and a lung abscess and was unable to attend the Bing Crosby Pro-Am. But he was up and about to narrate an American Sportsman’s show on the cheetah and efforts to conserve the threatened cat. In February he and Phil Harris flew to Alberta to hunt grouse and afterward, Bing headed down to Baja for a month of fishing at Las Cruces.

The following year, 1975, the Crosby family spent Easter in Las Cruces and enjoyed a month of fishing. Bing loved Las Cruces in the Sea of Cortez, and lived off his yacht until he built a home there. Mounted on the cabin walls of the True Love were some of Bing’s most spectacular trophy fish, among them a rare, world-record rainbow runner he caught on 12-pound test. “You gotta keep a hook in the water all the time to catch fish,” he said.

Bing and Phil with Jack Benny

He called these waters “the biggest bait tank in the world” and the best fishing grounds for striped marlin. He named his fishing boat Maria Francesca after his daughter, Mary Frances. It could go 30 knots and had a flying bridge and twin outrigger rigged for marlin. Bing used flying fish, mullet, or knucklehead for bait. “I’ve had them [marlin] take a feather,” he said. For marlin, he’d bait “two flying fish on 30-pound line, a squid on 20 pound, and a teaser on a light 10-pound line—it depends upon how hungry they are, or eager.”

In July Bing and his sons, Nathaniel and Harry, flew to Turnberry, Scotland, to play golf and remained on that side of the pond to head to Yorkshire in August to shoot grouse. The rest of the year they played golf.

Quite a lot of sport in a relatively short time for a man cresting 70.

And may all your Christmases be white

Bing left England on October 13, 1977, to play golf and hunt partridge in Spain. The next day he was at La Moraleja Golf Course, outside of Madrid, playing a round of 18 holes, despite his doctor’s warning not to exceed nine. He was in good spirits, pausing at the ninth hole to sing “Strangers in the Night” to a group of construction workers building a house nearby, who begged him for a song.

Bing and Phil with James Garner and Randolph Scott

He had a 13 handicap and lost the round by one stroke. “That was a great game of golf, fellas,” he smiled as he and his party headed back to the clubhouse. But about 20 yards away, he suffered a massive heart attack and was dead before he hit the ground. Bing Crosby was 74 years old. It was a fitting way for a golfer who loved the game so well to go out.

Tributes poured in from every corner of the globe. Millions wept. But perhaps the finest homage to this great and good and worthy man is this:

On April 29, 1975, the eve of the end of the Vietnam War, the U.S. Military Chain of Command issued a signal to be played over the Armed Forces Radio to order the beginning of the evacuation of all American troops from Vietnam. The war was over. Our boys were coming home.

That signal was Bing Crosby’s recording of “White Christmas.”

Editor’s Note: The Pinehurst Gun Club

Bing Crosby traveled to Pinehurst, North Carolina, many times to play golf on the crown jewel of Pinehurst Resort, Donald Ross’ Pinehurst No. 2, and to hunt bobwhite quail and shooting clays at the Pinehurst Gun Club. The Pinehurst Gun Club became a household word when “America’s sweetheart,” sharpshooter Annie Oakley, and her husband, Frank Butler, adopted Pinehurst as their seasonal home in 1915. Annie was the Pinehurst Gun Club’s first shooting instructor and Frank, its first manager.

In the course of their seven seasons in Pinehurst, Annie taught thousands of men and women to shoot—more than 4,000 women in her first two seasons here—while Frank’s many innovations changed the face of trap and skeet shooting and have been adapted in the design of the new Gun Club’s ten shooting fields, which include two 14-station sporting clays fields, golf green sporting, NSCA 5-stand sporting, trap, skeet, FITASC, Helice, flurry, and Olympic bunker traps. The first simulated pheasant tower in America, adapted from the European model, was built at Pinehurst Gun Club.

The Clubhouse on the Shooting Fields is inspired by the original clubhouse, built in 1895 by Pinehurst founder James W. Tufts, from which Annie Oakley taught. The estate, just under 500 acres, has two ponds and the members’ lodge, called Sealgair House (pronounced shall-e-gar, which means “hunter” in Gaelic) will be built on the peninsula that extends into Harding Pond. Sealgair House features a gun room, library, smoking room, and eight suites for use by members and their guests. The White Christmas barn is the dining room and, like Sealgair House, is inspired by the New England farmhouses portrayed in the films, White Christmas and Holiday Inn—both starring Bing Crosby.