After long days of hunting with no luck, it finally took a bit of native sorcery to make the difference on an elephant hunt.

The flight from Atlanta to Johannesburg provides those unwilling to embrace the charms of Ambien with ample opportunity to think. In point of fact, beyond ample. It offers a rare and uninterrupted block of time that is best used for pondering complex issues in great detail. I was somewhere in the throes of a pitched internal debate over which is the greater scourge, social media or rap music, when I realized that seated next to me was the son of the richest man in the world.

There are several ways to become rich. A few win a lottery. More than a few gain wealth via inheritance. Others get there dishonestly. Some manage to navigate the minefields of investing. Possibly the best way is to marry well, but that is a digression. Finally, there is hard work. The son’s father had worked for his measure, of that I was certain.

Unconsciously, I glanced in the young man’s direction. He must have sensed it, for he turned, took my hand in his and smiled.

“Thanks again for all this, Dad,” Ross said. “I can’t wait to see the Caprivi.”

I sputtered something intended as a response after realizing the last chapter of my son’s transition from boy to man was happening before my eyes. He was set to enter graduate school as soon as we returned home, and not long thereafter his wonderful wife was going to make him a father. All this was met with strong approval, even though it would be a long time before we could pull off a trip like this together again.

A solid definition of being rich is having the ability to do what you really want to do at a given time. For me, that’s hunting Africa’s dangerous game, and the only way to make it better is sharing the experience with Ross.

I didn’t have all this sorted out until a few months before while on a similar trip with a journalist friend on his first visit to Africa. We had just stepped off the little airplane at Katima Mulilo when he asked: “How does it feel to be back.”

“I feel like the richest man in the world, because if I was, this is still what I would be doing right now,” came my honest reply. Later, I turned those words over in my mind. The clarity was surprising, and it stuck.

“I feel like the richest man in the world, because if I was, this is still what I would be doing right now,” came my honest reply. Later, I turned those words over in my mind. The clarity was surprising, and it stuck.

Coming from a snowy Montana, Ross and I welcomed the summer heat of Johannesburg and passed our layover at a comfortable guesthouse where we talked mostly about the upcoming hunt. Our great friend and Professional Hunter Jamy Traut was already in position, waiting for us at his new camp in the heart of Namibia’s Caprivi Strip. We had the better part of two weeks to find Ross an elephant, his first. If luck was in abundance, there would be one for me as well.

I took advantage of the opportunity to explain the options we had, and accordingly, the decisions Ross might have to make on the fly. We would be hunting two adjoining areas, each with its own set of rules. Jamy’s camp was in the Kwandu Conservancy, where we were allowed to take both trophy and non-trophy bulls.

This distinction is important. Trophy bulls are just that – old-timers with big ivory, and a trophy permit allows the ivory to be exported. Non-trophy bulls, either old animals with broken tusks or mature bulls judged to be without the potential to become a trophy, are hunted on an own-use permit. Ivory covered by an own-use permit becomes the property of the conservancy. As is reasonable to suspect, the cost of taking a trophy bull is much higher, but the daily rate is static, for hunting elephants is hunting elephants. If no bull is taken, then no trophy fee is due.

Jamy’s other area, the Mayuni Conservancy, did not allow hunting of non-trophy bulls. However, it did divide trophy bulls into two classes according to the weight of the heaviest tusk.

An additional option in both areas was that an elephant could be designated as a problem by the Ministry of Wildlife at the request of local officials. Habitual crop-raiding or property destruction are primary reasons, and aggressive behavior toward people is never tolerated. In these cases, a problem animal control permit allows the hunter to take the troublemaker and, usually, to export the ivory.

As the associated trophy fees were most reasonable, Jamy knew that Ross and I were willing to drop everything if a promising opportunity was presented. No matter its classification, when an elephant is taken everything stops. Jamy must immediately employ people from nearby villages and bring them to the mountain so they can recover the skin panels and utilize every ounce of meat. Roads must sometimes be cut through several miles of bush, an effort that can extend well into the following day. No part of an elephant is ever wasted, regardless of logistics.

We were Jamy’s first hunters of the year, having agreed to brave the March heat and pardon interruptions as his staff got everything up and running. The camp proper was sprawled inside a curl of the Kwando River and was coming together nicely, but when we arrived the combination of heat and high humidity was as oppressive as a high school chaperone with a good flashlight and guilty memories. There was no thermometer, but it was pushing 100 degrees when we arrived. As for the humidity, if we were moving, then we were quickly soaked with sweat.

Elephant hunting in the Caprivi means wading through the many marshlands that crisscross this watery wilderness.

It’s always wonderful to see old friends, and a nice cluster of them rushed in to say hello before we cleared the truck. Harold Nobab took a moment’s break from directing the camp staff and greeted us warmly. The Bronner family – Dries, Renette and Reinhardt – were up from South Africa and they were an absolute joy to be around. As a bonus, 16-year-old Reinhardt was a good hand with a video camera and intended to make a feature-length movie of the doings. After three days of constant travel, we gladly accepted their insistent help and soon we were settled into a big, comfortable tent.

Ross and I had brought along a brace of Kimber rifles, appropriately designated as Caprivi models. The big stick was chambered in .458 Lott, a more powerful version of the .458 Winchester Magnum, and wore proper express irons. The other was a. 375 H&H Magnum, topped with the Leupold VX-6 1-6X scope in Talley quick-detachable rings. Loaded with solids, it could be used as a backup on elephants, and with softs, would serve well for just about anything else that drew our attention. Federal Premium Safari was, per usual, the ammunition of choice.

It’s common practice for conservancy officials across Africa to require that the professional hunter hire a game scout to accompany each party. A game scout with knowledge of animal movement and habits, the ability to gain information from locals and who has good tracking skills dramatically increases the chance of success. Michael Mahula was working with us in that capacity. I had the good fortune of hunting with Michael previously. He had proven himself an integral part of the team, finally working us right up to a grand old elephant bull that I probably should have taken.

Along with an assistant, Michael was waiting nearby. We picked them up and immediately began driving likely roads, searching for fresh elephant tracks. Once located, we would carefully examine each set. Unless made the night before, and then only if the impression of the front foot was at least 18 inches toe-to-heal, would anyone cast a second glance. Everyone got excited if a print spanned 21 inches or better, especially if the pad was deeply cracked and the heel showed the rounding that indicates old age.

The great truth of reading an elephant’s track is that a big foot doesn’t necessarily mean big ivory. Rather, a track can quickly have you believing what you want to believe, much like a personal profile on a dating site. Weight is usually something other than suggested and neither offers even the slightest hint that they might be broken. The only way to know for sure, in either case, is to execute a careful approach while maintaining cover and see for yourself. Should things not appear promising, one simply retreats before contact is made and resumes the search.

The Kwandu Concession – there’s that variable African spelling again – snugs up against Zambia, Angola and Bwabwata National Park. Elephants, especially older bulls, have a habit of swinging through Namibia at night to get a good feed and then crossing one of the borders to safety before sunrise. I had experienced this frustration before, but all of it was new to Ross. So when Jamy and Michael found a good track next to the border guard’s camp on the Zambia line and the guards told us that the bull had been there just hours before, he was first-morning excited.

It has been said that you hunt buffalo with your guts, leopard with your brain, lion with your heart and elephant with your legs. I don’t know which body part is required for the rhino needed to round out the big five, but when it comes to elephant hunting the legs analogy cannot be improved.

With its abundance of fresh water and lush vegetation, Namibia’s Caprivi Strip supports a healthy population of elephants and a goodly number of old tuskers.

After drinking water until I sloshed and making a fatherly suggestion to Ross that he do the same, we spun our rifles onto our shoulders and took up the track.

There isn’t much contour in the Caprivi. Otherwise, I don’t think it would have been possible to follow elephant in that heat. Even with the morning sun still touching the tops of the taller trees, I had soaked through my shirt before walking the first mile. Of course, the pace Michael and Jamy set was brisk.

Elephants stroll along at about six miles-per hour, and the bull’s track took us in a more or less straight line into the concession. Because the dung he left behind was cold, time had to be made up.

We walked hard on that track until well after noon, encouraged by freshening sign, but the bull eventually jinked back into Zambia. After fast-walking better than 12 miles, the slight chill of the Cokes waiting in the truck was received as a true luxury.

We spent the balance of the day searching for other tracks and found the greatest concentration in the area we’d started things off, solid proof that Jamy knew his area.

Several bulls and at least two breeding herds had been there recently, so we returned the next morning, picked up fresh tracks and followed a herd that was being shadowed by a pair of bulls. The heat was oppressive and the humidity even higher than the day before.

We followed the herd for several hours in near silence, not knowing where they might stop. They led us through open areas, then thick brush and finally under a canopy of huge, leafy trees that cast a mosaic of confusing shadows onto the cover below. The sign grew fresh. Michael indicated that he thought the herd would be resting soon, giving us an opportunity to close and discover if the bulls were with them. Jamy asked Ross if he was ready to look at some elephant up close and was answered by a most sincere smile.

We moved slowly and regarded each nuance of the wind. From above, our path must have appeared to be that of a disoriented snake. About an hour later Jamy signaled a water stop. The assistant game scout took a few steps ahead for some reason, possibly to find some privacy. At that moment, a Judas breeze ticked the back of my neck. Then a branch cracked and that was it. By the time we got to where the scout was standing, the herd was gone.

He had accidentally crept up on a sleeping bull just as the wind shifted. Thankfully, the bull had flushed like a quail in the direction he was pointing rather than coming around to get acquainted. Naturally, he took the herd with him. Hours and miles went down the drain in an instant, but it honestly didn’t seem to matter.

If the first two days were hot, humid and approaching a marathon, the third day was something beyond description. We again took up the trail of a good bull early. He was either walking with or following a breeding herd, and I felt good about this one for the illogical reason that we had discovered the track near the place where I had just months before shot a wonderful old leopard.

As we passed the bait tree, I pointed up at the bleached zebra bone wired to a limb and mouthed “next time” to Ross, knowing how much he wanted a leopard for himself.

We followed the elephant more or less past the spot where we had stampeded the others, continued for another couple of miles and finally began a slow crawl when the sign grew fresh. It was well over 100 degrees. Absent a hint of a breeze, it was like hunting in an oven. Twice the tracks crossed pee-soaked sand, where acrid fumes rose to burn my eyes. Riding on my shoulder, the rifle barrel became so hot that it threatened to scald my balancing hand if I didn’t frequently switch sides.

Worried about me, Ross kept asking in a whisper how I was doing. I shrugged the concern. No matter how hard it was to keep up, there was no way I was going to have him waiting for me. This might be the last time it could be that way, but when he glanced around I always flashed a concession-speech smile. I even managed one when we realized the herd had lined out for the nearby Zambian border and would likely cross before we could catch up. That particular smile was somewhat honest, as I didn’t want it to be over just yet.

The next several days were largely the same—long treks on trails leading to one border or another. Ross passed up a fantastic hippo bull, and we ignored the tracks of various plains game, even the western roan that I have wanted for so very long.

One morning, after picking up tracks with flashlights, we had followed a brace of bulls until they crossed into Zambia. We were circled up on a main road by the tracks, making a game plan for the balance of the morning when someone made a flip remark about how bad they wanted to at least see an elephant today.

“How about that one,” I asked flatly, as a gray form appeared in the distance. We scrambled to cut him off, found him to be a young bull with great potential, and let him go.

lt was that morning we came upon the track I’ve dreamed of my entire misspent life – the kind of track that Manners and Rushby and even Bell would have taken and never quit. A track made by the kind of elephant as rare today as a woman of virtue, the kind of elephant thought to walk only in Kruger or the Crater or maybe Khaudum, the kind of elephant that walks in the pages of a Wilbur Smith novel.

His track was enough over 22 inches to make it 23 without being thought a liar, deeply cracked and with a heel worn as smooth as the spine of grandma’s Bible. A young girl wearing a pink Disney t -shirt took us to it, explaining that the bull was among a group of frequent raiders worrying her father’s carefully cultivated maize field. Others from her village soon gathered and formed a complaining Greek chorus, enough so that we began entertaining the possibility of getting a problem permit.

We followed the tracks past the girl’s village and into braids of the Kwando River that marked the boundary of Bwabwata Park. The old bull was likely sleeping off his pirated feed under one of the trees we could see in the distance, untouchable. I wish it hadn’t mattered so much. I wish it still didn’t.

We worked our way through other nearby villages, hoping to find someone who might have information as to where we could set up and wait. Some responses were positive at first, but dimmed when pressed. We dropped the game scout at his office where he tried to get the bull declared a problem, but that effort failed for some reason. Even though we pulled out all the stops to find that bull on the right side of the boundary, we never knowingly came close. Before the hunt was over, I’d made arrangements to return during the dry winter months to try for him again. The hunt I had planned for Ross made the most of the time we had available. Spanning three weekends, it gave us 11 hunting days. We were having a great time, of course, but as the clock ticked away, I took Jamy aside and made adjustments. Should the opportunity present, Ross was to take either an own-use or trophy bull. If we blundered onto that monster hippo from early in the hunt, we would not worry about a shot frightening an elephant. Even with those additional options working, it was pretty quiet around the fire with only one day remaining.

I was willing to extend our hunt, as Ross had made it comically clear that he was willing to chuck his job if necessary. But Jamy was committed elsewhere, so there really were no options other than do everything we could to make something happen on the last day. What a day it was to be.

We found the tracks of a breeding herd at the waterhole with the old leopard bait before sunrise, and not long after discovered a bull track that seemed to be worth following. Jamy thought we should get on them quickly, rather than checking any other areas.

We trailed fast to the point of being almost reckless, spurred by the fingered dung that had become warm – me trying not to laugh out loud at how piles of increasingly fresh shit were making the spirits of grown men soar.

Pulling up for a water break, Michael set about gathering a handful of long grass and formed it into a circle. I watched with passing interest as he wrapped single stalks at approximate intervals around the circumference to hold it in position while speaking softly in Afrikaans to Jamy.

“Michael believes we should try to bind the elephant, to keep him content and feeding so we can approach,” Jamy volunteered. “We must all place our rifle barrels into the circle at the same time for this to work.”

In for a penny, we followed instruction without hesitation. For my part, I was prepared to do most anything to change our luck. We took up the trail again, now beyond caring about the heat and sunburns and water that was running low. We lost the track several times, but Michael and Jamy sorted it out while the rest of us waited in what passed for shade. Michael was still carrying his magic circle, and as he motioned us forward after picking up the track, I noticed that he was also holding several small green branches.

“Those are twigs broken by the elephant as he fed. Michael believes that by carrying them we will be drawn together with the elephant,” Jamy explained.

It wasn’t but minutes later when we heard a limb snap somewhere just ahead. After crowding together, Jamy signed us to stop and then walk single-file. We closed by ear, altering course as branches split, guts rumbled and cows said an occasional something or other to a misbehaving youngster. Kids, I thought, same everywhere.

Leading the scrum such that he was, Michael was the first to see an elephant. He predictably froze and the rest of us just as predictably ran up each other’s backs. Maybe 30 yards away, a cow had noticed our movement and squared off, but the slight breeze was favorable and we luckily had some cover.

I watched her over Ross’ shoulder, remembering a similar circumstance a year earlier that ended with an enthusiastic gunfight at a half-dozen steps. Ears flared, her head took on the shape of Texas, or more accurately, Texas with an evil glare. Realizing something wasn’t right, she raised her trunk and twisted it back-and-forth like a cobra being charmed from a basket. Thankfully, the breeze held. There was nothing to do but wait.

About the time I was convinced things were going to work out, a small calf appeared and nudged against the cow’s front leg. Now I wasn’t so sure. In anticipation of what might happen, Ross slowly lowered his right shoulder and began to balance his weight so the Lott could come into play at the shortest possible time. That made me proud, too.

The calf was either restless or had a mind of its own, for it soon began to move off and away. Mom cast one last dose of stinkeye in our general direction, slicked every thing down and then followed. She looked much smaller after changing posture. We gave her some time, then started to circle in hopes of locating the bull.

One of the constant challenges throughout our hunt was the wind that would begin to swirl during the midday heat, seemingly while we were making an approach. It did just that as we cut a corner and began to follow a faint opening we hoped would bring us back into the herd. I don’t know how far away the elephant was that caught our scent and trumpeted the alarm, but it was so loud that I expected a trunk to grab me with a boarding-house reach any moment.

We all froze, this time without waiting for Michael to set the example. I expected to hear elephants running, inbound or away, but there was only quiet.

After holding position for several minutes, Jamy motioned us forward again. Michael picked a careful trail, and it wasn’t long before he pointed at something. Following his line, I noticed the top of a tree shaking. The gray mass doing the shaking was nearly hidden in its shade. Jamy turned and mouthed “bull,” and then most redundantly asked Ross if he wanted to take him.

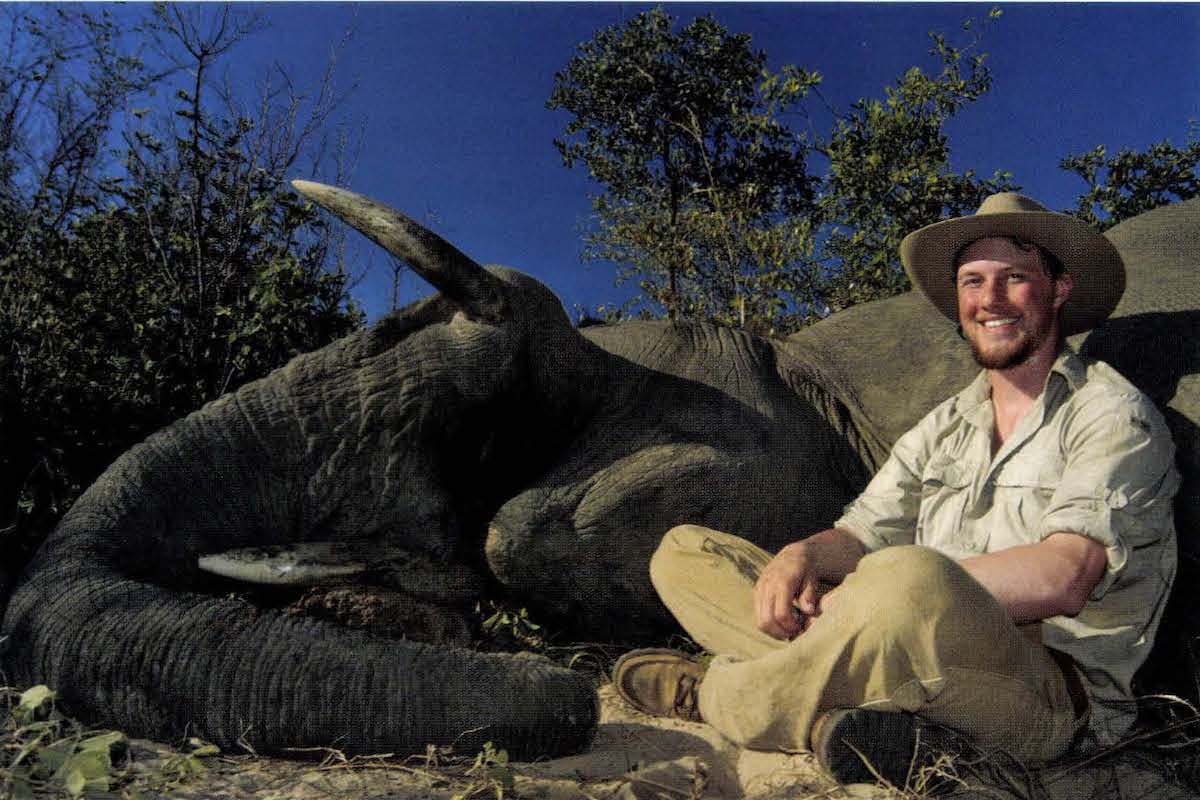

Ross Van Brunt happily poses with his bull, which he killed on his 11th and last day of hunting in the Caprivi. On their safari, the hunters logged many miles of tracking different bulls in temperatures that soared to well over 100 degrees.

The bull was facing directly away from us at 40 yards. It was logical to assume we would begin a very careful, slow approach to within fly-swatting range and then wait for him to turn. Jamy had something different in mind, however. He waited for the bull to reach up into the tree for another branch and then took off at a fast walk, cutting the distance to 14 yards in a matter of seconds. He then moved to the side and brought Ross forward. I bookended them on the right.

Ross snapped the rifle to his shoulder as soon as he cleared Jamy. Someone behind us shifted to get a better view and in doing so made a little noise. It wasn’t much, but certainly enough. The bull whirled to face us, and as he did he got a whole lot bigger.

Elephants are surprisingly fast, and when the bull spun around, he seemed to cut the distance between us nearly in half. Only he didn’t complete the turn. Ross’ bullet drilled into the bull’s head and continued on through the brain. The effect was immediate. The hind legs buckled first, cantilevering its great head up and back with the trunk curling above it all with the motion of a cracking whip. As the head came level, there was another shot. Then there was only dust.

I jerked my head first Ieft and then right, convinced we were about to be overrun if only by accident. Elephants crashed through the brush and trees all around. Then they were simply gone.

Jamy and Ross moved up, and after his insurance shot, Ross accepted congratulations through a fog of emotion. I waited for everyone else to finish, then smothered him in a hug. He hugged back, too, hard enough that my ribs cracked. Some minutes later I asked Jamy why he almost immediately followed Ross’ shot, as it clearly had killed the elephant.

“I didn’t,” he replied flatly. “Ross fired both times.” It took a bit of convincing for me to believe it, and then I was even more proud.

We knocked out pictures, and while doing so I found a chunk of broken ivory just steps from the bull. It had been there for some time, and I challenged Ross to try and find a whitetail shed back home that would be its equal. The elephant had taken us in a great circle, so we were back to the truck in something less than two hours of walking.

At camp we gathered up a crew to recover the meat and once that was done, we led a second truck back to the bull and took some final photos.

Later that night, Reinhardt finished his movie by filming Ross and me telling the story. At the conclusion, I reached into a battered cardboard box that had passed through many hands during the past year and carefully withdrew a book. Telling Ross that another elephant hunter wished to extend congratulations, I presented a copy of Use Enough Gun inscribed to him by author Robert Ruark’s professional hunter. It read:

To Ross Van Brunt,

Wishing you all the very best.

Your friend,

Harry Selby

We stopped by Michael’s home on our way to the airport to give him something that better expressed our genuine appreciation. I also told him that I would be returning in a few months and hoped that his magic wreath and gathered branches would work once again, binding me to the bull with the big track. Hopefully, he won’t hold it in reserve until the last day.

By Dwight Van Brunt

Join the author as he pursues the world’s greatest big game animals. Supported by excellent color photos and 25 superb illustrations, the 288-page book is a must-read for anyone who thrills to hunting big game. Buy Now