The muzzleloader had taught me to economize ammunition, and now, when I had a rifle, I considered it wasteful to practice on a fixed target, so I practiced on jungle fowl and on peafowl, and I can recall only one instance of having spoilt a bird for the table.

I never grudged the time spent, or the trouble taken, in stalking a bird and getting a shot, and when I attained sufficient accuracy with the rifle to place the heavy .450 bullet exactly where I wanted to, I gained confidence to hunt in those areas of the jungle into which I previously had been too frightened to go.

One of these areas, known to the family as the Farm Yard, was a dense patch of tree and scrub jungle several miles in extent, and reputed to be “crawling” with jungle fowl and tigers. Crawling was not an overstatement as far as the jungle fowl were concerned, for nowhere have I seen the birds in greater numbers than in those days in the Farm Yard. The Kota-Kaladhungi road runs for a part of its length through the Farm Yard, and it was on this road that the old dak runner, some years later, told me he had seen the pug marks of the “Bachelor of Powalgarh.”

I had skirted round the Farm Yard in the bow-and-arrow and muzzleloader days, but it was not until I was armed with the .450 that I was able to muster sufficient courage to explore this dense tree and scrub jungle. Through the jungle ran a deep and narrow ravine, and up this ravine I was going one evening, intent on shooting a bird for the pot or a pig for our villagers, when I heard jungle fowl scratching among the dead leaves in the jungle to my right. Climbing onto a rock in the ravine, I sat down and, on cautiously raising my head above the bank, saw some 20 to 30 jungle fowl feeding towards me, led by an old cock in full plumage.

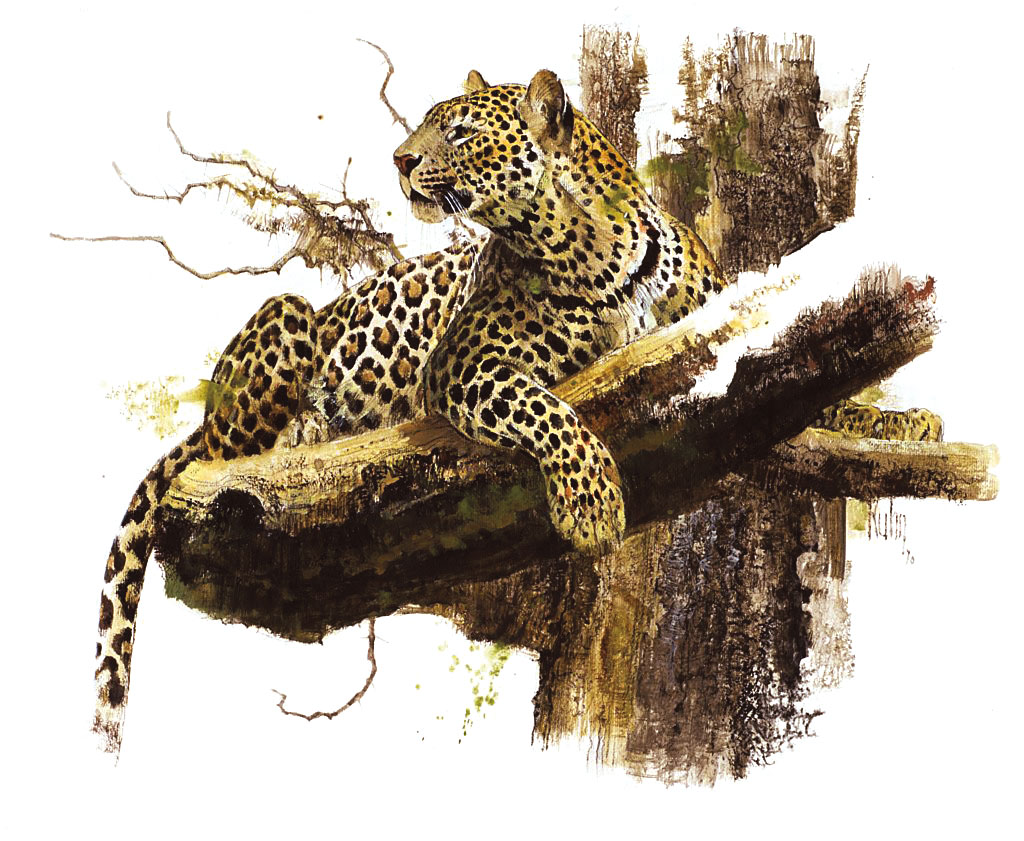

Selecting the cock for my target, I was waiting with finger on trigger for his head to come in line with a tree—I never fired at a bird until I had a solid background for the bullet to go into—when I heard a heavy animal on the left of the ravine, and on turning my head I saw a big leopard bounding down the hill straight towards me. The Kota road here ran across the hill 200 yards above me, and quite evidently the leopard had taken fright at something on the road and was now making for shelter as fast as he could.

The jungle fowl had also seen the leopard, and as they rose with a great flutter of wings, I slewed round on the rock to face the leopard. Failing in the general confusion to see my movement, the leopard came straight on, pulling up when he arrived at the very edge of the ravine.

The ravine here was about 15 feet wide with steep banks 12 feet high on the left and eight feet high on the right. Near the right bank, and two feet lower than it, was the rock on which I was sitting; the leopard was, therefore, a little above and the width of the ravine from me. When he pulled up at the edge of the ravine, he turned his head to look back the way he had come, thus giving me an opportunity of raising the rifle to my shoulder without the movement being seen by him.

Taking careful aim at his chest, I pressed the trigger just as he was turning his head to look in my direction. A cloud of smoke from the blackpowder cartridge obscured my view, and I only caught a fleeting glimpse of the leopard as he passed over my head and landed on the bank behind me, leaving splashes of blood on the rock on which I was sitting and on my clothes.

With perfect confidence in the rifle, and in my ability to put a bullet exactly where I wanted to, I had counted on killing the leopard outright and was greatly disconcerted now to find that I had only wounded him. That the leopard was badly wounded I could see from the blood, but I lacked the experience to know—from the position of the wound and from the blood—whether the wound was likely to prove fatal or not. Fearing that if I did not follow him immediately he might get away into some inaccessible cave or thicket where it would be impossible for me to find him, I reloaded the rifle and, stepping from my rock onto the bank, set off to follow the blood trail.

For a hundred yards the ground was flat, with a few scattered trees and bushes, and beyond this it fell steeply away for 50 yards before again flattening out. On this steep hillside there were many bushes and big rocks, behind any one of which the leopard might have been sheltering. Moving with the utmost caution, and scanning every foot of ground, I had gone halfway down the hillside when from behind a rock, some 20 yards away, I saw the leopard’s tail and one hind leg projecting. Not knowing whether the leopard was alive or dead, I stood stock-still until presently the leg was withdrawn, leaving only the tail visible.

The leopard was alive, and to get a shot at him I would have to move either to the right or to the left. Having already hit the leopard in the body, and not killed him, I now decided to try his head, so inch by inch I crept to the left until his head came into view. He was lying with his back to the rock, looking away from me. I had not made a sound, but the leopard appeared to sense that I was near, and as he was turning his head to look at me, I put a bullet into his ear. The range was short, and I had taken my time, and I knew not that the leopard was dead, so going up to him I caught him by the tail and pulled him away from the blood in which he was lying.

It is not possible for me to describe my feelings as I stood looking down at my first leopard. My hands had been steady from the moment I first saw him bounding down the steep hillside and until I pulled him aside to prevent the blood from staining his skin. But now not only my hands but my whole body was trembling: trembling with fear at the thought of what would have happened if, instead of landing on the bank behind me, the leopard had landed on my head. Trembling with joy at the beautiful animal I had shot, and trembling most of all with anticipation of the pleasure I would have in carrying the news of my great success to those at home who I knew would be as pleased and as proud of my achievement as I was.

I could have screamed, shouted, danced, and sung, all at once and the same time. But I did none of these things; I only stood and trembled, for my feelings were too intense to be given expression in the jungle, and could only be relieved by being shared with others.