We thought Bill Cypress was as close to perfection as human beings ever got.

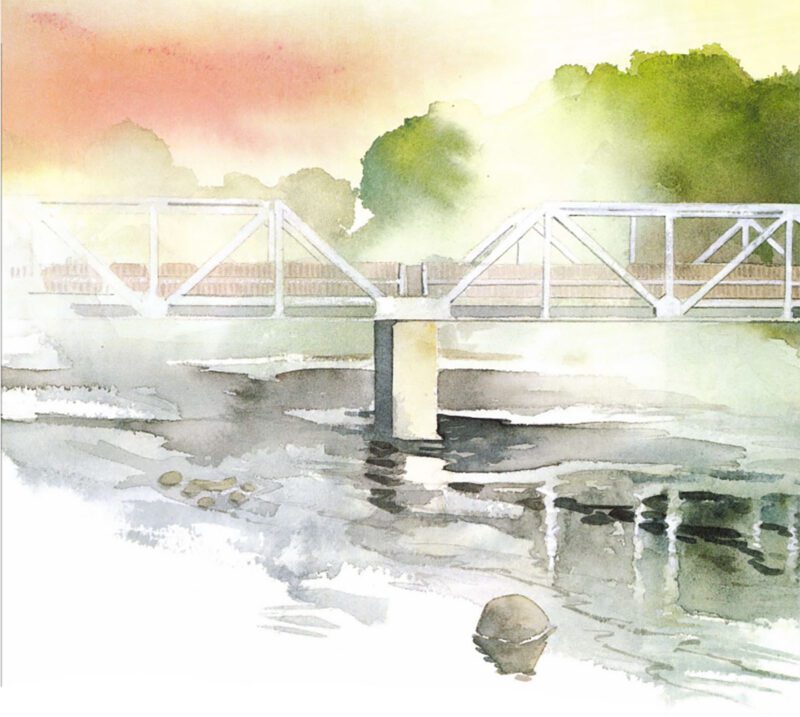

State Highway 16 ran south out of town. Not straight south — not to start, anyway. It had to work its way out of the hills first and make a couple of gentle turns past the new high school before it settled down to run level and true on the lowlands. Four miles from town it passed high over the Sabine River on an old trestle bridge.

State Highway 16 ran south out of town. Not straight south — not to start, anyway. It had to work its way out of the hills first and make a couple of gentle turns past the new high school before it settled down to run level and true on the lowlands. Four miles from town it passed high over the Sabine River on an old trestle bridge.

Lester and I mounted our bicycles one moist summer morning and set out on Highway 16. We were carrying our fishing tackle and a coffee can of the best, juiciest worms we could find. The plan was to spend the day on the banks of the muddy Sabine catching monster catfish.

The sun was just above the oak trees when we got to the bridge. We stood a minute and looked over the bottom. The haze was just beginning to burn off, and in the morning light everything was colored that intense, early summer green that’s so bright it’s almost iridescent. The cowbirds were going out for the day, and they floated in clusters of little bronze dots above the trees.

It was a mighty pretty morning all right, but we were there to fish, not admire the scenery. We walked our bikes down beside the bridge, laid them under the trestle, and headed upriver.

Lester and I didn’t have much experience at river fishing. We were amassing what you would call “on the job training.” The first thing we learned is that a riverbank is a lot slicker than it looks. We slipped and stumbled our way upstream, and almost spilled our precious worms twice.

We finally arrived at a stand of willow trees. Their roots were woven tenaciously into the silty bank, and their long, trailing branches draped into the water and made a natural canopy.

This was the place for monster catfish, no doubt about it. The water was wide and running fast enough to make ripples on the surface. We weighted down, baited up, and sank our lines into the brown water. Then we sat back for what we knew would be a short wait until those big fish jumped on our lines.

And waited … and waited …

By 10 o’clock the air wasn’t soft anymore. Matter of fact, it was getting downright steamy even under those willows.

Lester and I hadn’t entertained a nibble between us. What’s more, neither of us had thought to bring food or water, and we were starting to regret it.

We sat there in mutual misery, both stubborn, neither wanting to be the first to quit. We sat there and prayed silently for relief.

Suddenly a huge racket began echoing up and down the river. Down by the bridge, somebody was clanging metal against metal and hollering the kind of words we only heard when the adults thought we weren’t around.

I took one look at Lester, and we were decided. Whatever was going on down there was much more interesting than what we were doing up here. We collected our gear and headed back toward the bridge.

Whoever it was, and whatever they were doing, they weren’t doing it at the bridge. The bank came to a point about 50 yards below the bridge. We made for that.

The sound had stopped. We eased around the point, being as quiet as we could be carrying all that gear.

Past the point, the bank was cut back into a hollow. In that hollow sat a cabin.

It wasn’t much to look at. It was small and square and sitting high above the bank on piers. The door stood five feet or so above the ground and faced the river.

The shack had a steep, tin roof, and you could see where the nails were because they had corroded and bled orange on the tin. There were windows, a small one on each side of the door, but the sills were grey and splintered. The whole thing was walled in black, asphalt board, and stained mud brown about halfway down.

There wasn’t a porch, just steps that led to the door. They weren’t like steps you see on most houses, though. They were made of a lot of short pieces, all nailed together at crazy angles. The way they looked, you wouldn’t put your hand on them for fear they’d fall down.

We could see a dented flat-bottom boat pulled under the house, but we couldn’t see any people. We were curious and mighty thirsty. We walked slowly toward the door.

We came to a stop at the bottom of the steps. The door was open, and we stood peering into the cabin’s darkened insides, trying to decide what to do next.

“You young ‘uns after something?”

We both jumped. There was a crash as our rods, our tackle boxes, and our prized worms hit the ground.

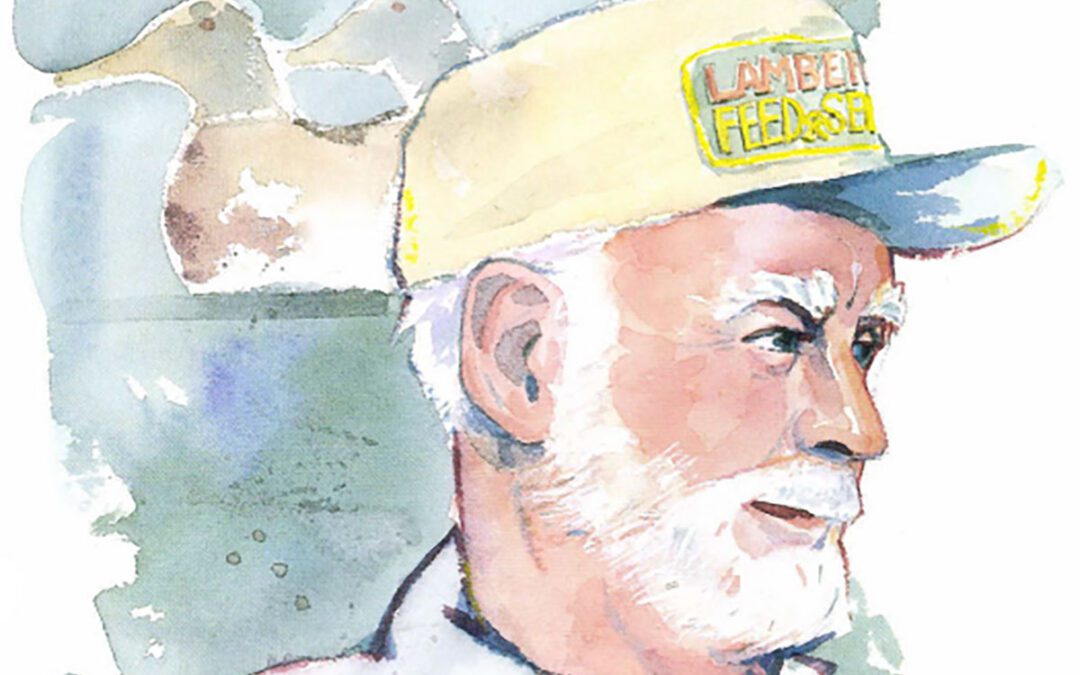

A man had come around from the side. Like the shack, he wasn’t much to look at. He was short, and had a few wisps of curly, grey hair sprouting out from under a greasy Lambert’s Feed and Seed cap. He had a big gut that hung out and twisted his belt, and round, red cheeks just like Santa Claus.

Unlike Santa Claus, though, he had a ball peen hammer clenched in his fist.

For a few anxious moments, I didn’t know whether to stay put or run. Fishing gear could always be replaced, but there wouldn’t be any need if Lester and I were bludgeoned to death by a hammer murderer.

“Water,” Lester blurted out in a high, squeaky voice.

“Water?” The man paused to scratch the stubble on his jaw. “Plenty of that in the river.”

“He means drinking water,” I said. Evidently, I wasn’t going to run. “We’re real thirsty.”

He pointed with that hammer to the side of the house. We went around, making a discrete, but wide, path around him. There was a rusty faucet sticking out of the ground.

It wasn’t pretty, but that faucet flowed well water, cool and sweet. We stopped, finally, quenched and a little bit waterlogged. The old man had been studying us as we drank.

“What’s a couple of boys doin’ down here on the river, anyway?” he asked.

“Well, we were fishing,” Lester said, “But we didn’t even get a bite.”

He didn’t say anything to that, just turned and headed behind the shack. Not knowing what else to do, Lester and I followed.

There was a rusted 55-gallon drum out back, and inside was an old outboard motor. Most of one, anyway. Pieces of engine intestine lay scattered over a wide area. I figured that was what the clanging was all about.

When he noticed we were following him, the old man turned and fixed us with a steady stare.

“The river ain’t no place for kids,” he said, “You could get drowned, or you could get snake bit. I seen cottonmouths big as logs in that river.”

I shivered involuntarily. I’d heard snake stories all my life. It didn’t make me like them any better.

The old man must have noticed my discomfort.

“Yeah,” he continued, working up steam. “And them cottonmouths ain’t even the biggest. Last year I kilt a timber rattler seven feet long. Wasn’t fifty yards from the river. He was big around as my leg. Who knows? A snake like that might have enough venom to kill a hundred men.”

Me? I was a believer. But Lester was made of sterner stuff.

“There’s no seven-foot snakes around here,” he said, “You’re just making that up.”

The old man dropped his hammer and took a hold on both our arms. He herded us back around the cabin, out past a garden plot that had mostly surrendered to the weeds, and about twenty yards beyond where a pumphouse stood in head-high weeds.

Nailed to that shed was the biggest snakeskin I’d ever seen. It hung from the roof down to the ground and stretched three planks wide. I looked at Lester. His eyes were like new moons. Now he was a believer, too.

The old man seemed inordinately pleased at our stares. He rocked back with a satisfied grin and dug a plug of tobacco out of his shirt pocket.

“I’ve been fishing this river longer than you boys been alive,” he said, gnawing off a chew, “If Bill Cypress tells you something, you can take it to the bank because it’s the truth.”

We followed him back around to the front of the shack. He sat himself down on those rickety steps like a king preparing to hold court.

“You boys usin’ worms for bait?” he asked, eyeing our coffee can.

“Yessir,” I said. The can was on its side where I had dropped it. I scraped what worms were left and retrieved the can to show him. He dug around in it with grimy fingers.

“Them’s good worms all right,” he said, “But for these old river catfish, blood-bait’s better. Where you been fishin’?”

“Up by some willows;’ Lester said and pointed back above the bridge.

Bill gave a disgusted snort. “Well, that’s your problem. You won’t never catch no fish up there. Water’s too shallow. You got to find a hole if you want to catch catfish.”

He got up, seemed to study the river for a moment, then ambled inside the shack. In a minute we heard some banging around, and him cussing some more. He emerged after a few minutes with a beat-up rod and a gallon paint can of something that, even sealed up, smelled awful.

“Blood-bait,” he said, noticing our faces, “I make it up myself. I usually use it on a trot line, but I guess somebody ought to teach you young ‘uns about the river so’s you won’t get yourselfs killed.”

Without giving us time to say anything, he headed for the river. There was a trail meandering along the bank, and Bill walked it like he was going to a fire. Lester and I scrambled to keep up.

At one point the trail made a wide detour around a stand of switch cane.

“That’s a bad place for snakes;’ he said, pointing to the canes. ‘Any time you get canes, you’re going to get snakes. Canebrake rattlers, mostly, but sometimes you’ll find a copperhead or a timber rattler or maybe even a big diamondback.”

“What do you do if you find one?” Lester asked. Bill stopped right there on the trail.

“Listen, young ‘uns;’ he said, ‘And I’ll tell you. The most importantest thing to remember about a rattlesnake is that he don’t want no trouble. He’ll most always rattle to let you know where he is, then you can keep out of his way. The only time you’ve got to worry is if you startle one.

“Rattlers like to lay around next to fallen logs, so you watch before you step. That’s all you got to remember, a rattler don’t want no trouble. If you run into one, just be still, and he’ll leave you alone.

“A cottonmouth, he’s another story. He’s mean. If you mess with a cottonmouth, he’ll likely come after you just for spite. And don’t believe it if anybody tells you a cottonmouth can’t bite underwater. I seen a guy bit 12 times by cottonmouths. He was standing waist deep in the water seining for minnows. He died in less than an hour.

“Cottonmouths are trouble, but keep your eyes open and look before you step, and you won’t ever have problems with a rattle snake.”

That was the end of the lecture. He started up again with that rapid walk.

We had gone about a mile upstream when Bill pulled up and pointed to a sharp bend in the river.

“See how that water’s calm in the hollow of that bend?” he asked. “Calm water means deep water. There’s a hole there so deep it never goes dry. That’s the place to look for catfish.”

So we sat down there on the bank above the river and rigged our lines. Bill pried the lid off of his can. The stuff inside looked like reddish-orange jelly, and once the can was open, the smell was almost too much to take.

“That’s what these old catfish like,” Bill explained, “The more it stinks, the better they like it.” He dug out a pocket knife and carved a piece of it to put on his line. Lester and I looked at each other.

“I ain’t your momma,” Bill growled, “If you want to fish, you gotta’ bait your own hook.” He tossed his line into the water.

I decided it was time to be brave. I took the knife and plunged it into the foul-smelling stuff and managed to cut off a sliver. It’s harder when you’re holding your breath.

I baited up and gave the knife to Lester. I let my line out the way Bill had.

“Just go to the bottom and let it lay. “You need more weight in the river because of the current. Now bring your line up to where it’s just tight. Yeah, like that.”

“Okay,” I said, “Now what?”

Bill leaned back and dug out that plug again.

“Now you relax and wait,” he said. Lester had managed to bait up and get his line out, too. We sat there, exchanging furtive glances.

But we didn’t sit long. Suddenly my rod began to dance. I jerked hard, and stood up to reel in a nice four-pound channel cat. Bill looked at it approvingly as it flopped on the bank.

“What’d I tell you,” he said, ”Ain’t nothin better than blood-bait for these old river catfish.”

He was about to say more, but his rod started wiggling too. He lunged back and reeled out a nice fish of his own.

“Say,” he said, his eyes dancing, “I’d forgot how much fun this is with a pole. I’ve been baiting trot lines so long I forgot there was any other way to do it.”

I caught another one, about a pound or so, and then Lester caught one. It settled down a bit after that, but we didn’t really mind. We sat on the bank while the wind waved in the oak trees and listened to Bill tell stories about the river and the woods around it and about how it was when the ducks came in by the thousands and passenger pigeons flew in black streams that ran for hours.

The heat was off of the day, and even Bill was starting to drag a little when I finally realized I was hungry. More than that, I was hungry the way only a boy can get hungry, which meant I was as empty as the Grand Canyon. I saw Lester eyeing the fish we had caught and figured he was about the same. Bill must have picked up on it.

“Say, you young ‘uns getting hungry?”

“Uh, well… maybe just a little;’ I said. He ruminated on that moment, and then looked up at the sky.

“Well, I expect it’s about three o’clock. Can’t see the sun, though, so I can’t be sure. Let’s ease on back to the shack and see what we can rustle up.

The trip back was longer than the one out, and it wasn’t made any easier by the heavy stringer of catfish we were lugging. Lester and I took turns carting it. Bill navigated.

We came around a bend at last to the sight of that old, ramshackle cabin. We dumped the catfish under a tree and followed Bill inside. There was a large front room, lit by a single lightbulb hanging on a wire. To the right was a couch and chair that looked like refugees from the junkyard. A huge mound of traps lay piled against the left corner. There were some wood decoys with the paint mostly eaten off, and an Evinrude outboard from the days when they were still green and had a pearl-shaped cowling.

There were two rooms off in the back; their doors met in the center. One was a bedroom, the other was a kitchen.

Bill ambled to the kitchen. An iron stove took up one wall, and on top of it was an old dutch oven filled with grease.

Lester and I got big drinks out of the tap while Bill stoked a fire in the stove. Once he had that going, he sent us out to the garden to salvage what squash and okra we could find. Meanwhile, he drew a bucket of water and went back out to the tree where we had left the catfish.

Lester and I found quite a bounty out there in the weeds, and we had more than enough to eat in a short time. We went out to watch Bill at work under the tree.

Bill had a system, and it was as slick as I’ve ever seen. I hadn’t noticed before, but there was a large spike driven into the tree about five feet up. Bill hung a fish on the spike, and skinned it was a pair of pliers.

He made it look as easy as taking Doctor Denton’s off a baby. He had a mess of fish skinned, cleaned and ready to fry before the grease was hot.

Back in the kitchen, he dug some corn meal out of a rusty canister and dumped it in a bowl that looked like it hadn’t seen water in a while. In no time he had fish popping in the pot, and squash and okra to follow.

When it was ready, we sat where we could. Bill didn’t offer us any silverware, but it didn’t really matter. I nearly burned my fingers off getting that sizzling food into my mouth.

I could say it was the best fish I ever tasted, but it wasn’t. This was in the days before catfish farms, so it wasn’t some pampered, domestic fish that had never known anything but Purina Fish Chow. It was river fish, and it tasted of Sabine River mud.

But it was good enough. We ate until there wasn’t any more. And when we got ready to leave, we were so full we could hardly peddle our bikes.

Bill didn’t say much in the way of goodbye. He gave a sort of half wave, dug another chew out of his shirt, and headed back to that old outboard like he’d never been interrupted.

And Lester and I, we weaved our way home, riding that long, straight stretch of Highway 16 and talking excitedly about old Bill.

We were at an impressionable age, an age when adult society and its rules don’t mean much. We were too young to understand that men like Bill Cypress never make the social register. That they never get invited to a Rotary Club lunch. That they seldom, if ever, darken the door of the local church. We didn’t realize you don’t become a success living in a shack by the river and doing as you please every day.

We were at an impressionable age, an age when adult society and its rules don’t mean much. We were too young to understand that men like Bill Cypress never make the social register. That they never get invited to a Rotary Club lunch. That they seldom, if ever, darken the door of the local church. We didn’t realize you don’t become a success living in a shack by the river and doing as you please every day.

None of that was apparent to us at age 14.

We thought Bill Cypress was as close to perfection as human beings ever got.

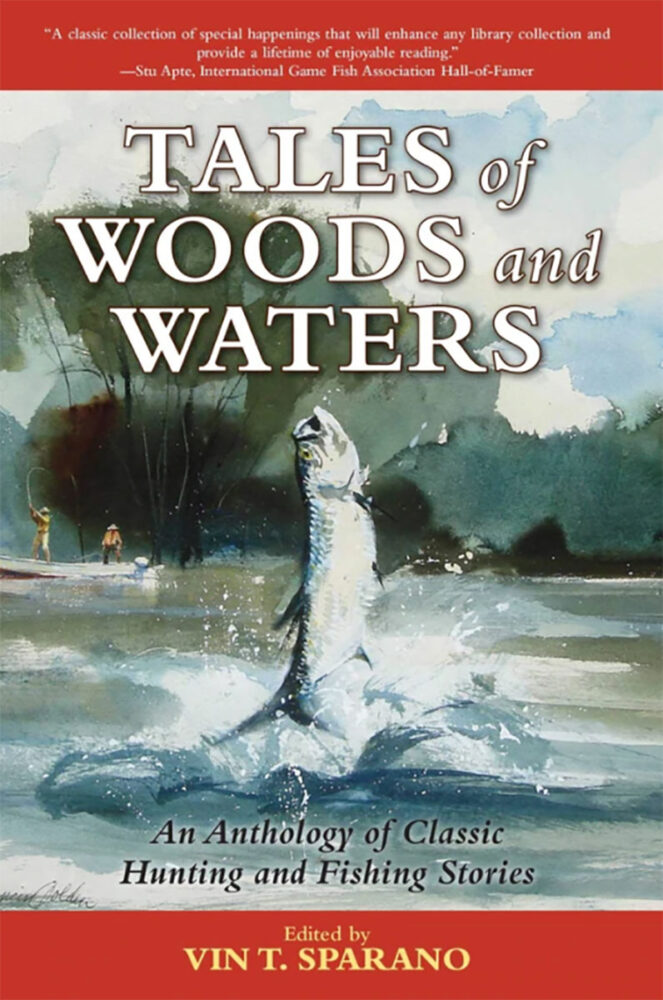

In Tales of Woods and Waters, well-known outdoor editor Vin T. Sparano has collected thirty-seven of the greatest, most enjoyable, and most well-written outdoors stories to have been published. Experience the tension of hunting in the jungles of Tanzania in Jim Carmichael’s “Kill the Leopard,” the joys of your first .22 in Garth Sanders’s “My First Rifle,” the nuances of river fishing in Frank Conaway’s “Big Water, Little Men,” and the enduring challenge of turkey hunting in Charles Elliott’s “The Old Man and the Tom.” Spanning the world and its varied forms of wildlife, these stories demonstrate that no matter where one hunts, shoots, or fishes, the outdoors will always be an important place to form memories that last a lifetime. Buy Now

In Tales of Woods and Waters, well-known outdoor editor Vin T. Sparano has collected thirty-seven of the greatest, most enjoyable, and most well-written outdoors stories to have been published. Experience the tension of hunting in the jungles of Tanzania in Jim Carmichael’s “Kill the Leopard,” the joys of your first .22 in Garth Sanders’s “My First Rifle,” the nuances of river fishing in Frank Conaway’s “Big Water, Little Men,” and the enduring challenge of turkey hunting in Charles Elliott’s “The Old Man and the Tom.” Spanning the world and its varied forms of wildlife, these stories demonstrate that no matter where one hunts, shoots, or fishes, the outdoors will always be an important place to form memories that last a lifetime. Buy Now