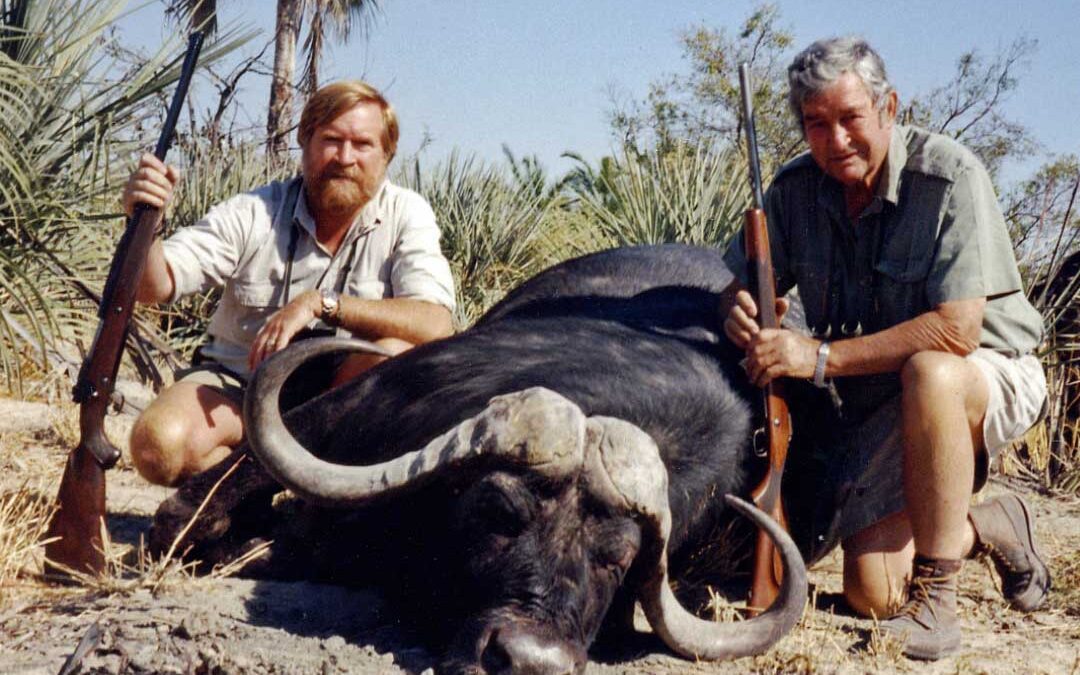

Just when you think you have hunting dangerous game figured out, a wake-up call comes knocking, usually during the follow-up of a wounded animal. I remember an important lesson learned during one particular buffalo encounter that was certainly a close call.

It was April in northern Botswana and the rains had recently finished, leaving the savanna carpeted in knee-high grass and mopani trees canopied with leaf. We were camped in Ker, Downey & Selby (KDS) Safari’s Mababe Concession, a prime early-season game area located south of the Chobe National Park and northeast of the Moremi Game Reserve. We’d just begun a 14-day safari and were focused on finding elephant and buffalo with some plains game thrown in. My client was an experienced hunter with whom I’d previously hunted, so we knew each other well enough to know what to expect from each other.

On the third morning we rolled out of camp before first light and headed for an area where I expected to find fresh elephant sign. Plentiful water and forage had the elephants and buffalo scattered throughout the concession, but we found fresh tracks of a good bull near a large pan where he had drunk the previous evening. Hoping to catch up to before he covered too many miles, we began a quick-paced walk on his tracks. But as hunting luck would have it, nearly an hour into our elephant pursuit we crossed paths with a single old buffalo bull grazing on the lush grass growth. We decided to take advantage of the opportunity and stalked closer for a better look.

Approaching to within about 40 yards of the old bull, I could see that he was “imminently shootable” in both age and horn-spread. The client wasted no time shouldering his rifle and squeezed off a shot. The 500-grain, .458 solid bullet smacked the bull behind the shoulder, causing him to buck and take off at a run. He ran for about 50 yards before going down, still within sight. This was a slam dunk, I thought to myself—this old guy will give us no trouble.

The buff was still alive and tossing his head about as we approached, seemingly oblivious to our presence. I assumed his struggles were his death throes as we watched from about 20 yards away. I suggested to the client that he put a finishing shot into the buffalo, but the angle at which we stood prevented a clear shot. I didn’t want to risk damaging the horns with a hit from a solid bullet, so I told the client to take a step to the right for a better shot angle.

As the client took one step sideways the buff was instantly on his feet. He moved so quickly there was no time to be surprised. The buff pressed forward in a headlong rush straight at us and we both fired as quickly as we could. Two 500-grain, solid bullets simultaneously slammed into the buffalo, killing him mid-stride and causing his legs to buckle beneath him. Our two bullets struck the buff between the eyes within a couple of inches of each other.

We reloaded and fired again to be absolutely certain the bull stayed down. It was a dramatic lesson that might have had a far less happy ending had our shots missed the brain. It was an encounter that clearly demonstrated how crucial it is to remain ready when in close proximity to a dangerous animal, wounded or otherwise. After watching a number of buffalo go down on previous hunts without a hint of trouble, I’d been lulled into thinking a downed animal was down to stay. We should have administered a finishing, or insurance shot, much sooner rather than wasting time discussing shot angles.

“To hunt dangerous game you need to be scared enough to be cautious and brave enough to control your fear…and use enough gun.”

—Robert Ruark, 1956

The element of danger adds a whole new dimension to the hunt, and for which there are no guarantees of safety. The close approach to large animals that can bite, scratch, impale or stomp you into tattered bits should only be attempted when carrying a rifle designed for that purpose—best described as a “big bore.” Our big bore rifles offered the last chance to stop a ton of angry attitude from inflicting serious injury—or worse.

Big Bore Rifles & Calibers

Whenever hunting Africa’s Big Five—elephant, rhino, buffalo, lion and leopard—or any of North America’s big bears—your safety, and possibly even your life, relies on your rifle’s capacity to fire a large bullet with enough energy to stop the largest game. Holding a big bore cartridge in your hand makes it seem unduly large and cigar-like, but when faced with a dangerous animal’s charge, a 500-grain .458 bullet will not seem nearly large enough.

(From left) 375 H&H Mag., 404 Jeffery, 416 Rigby, 458 Win. Mag., 458 Lott, 500 NE.

Prior to the mid-1970s when hunting was still allowed in Kenya, Kenya Game Department regulations stipulated that the thick-skinned game (elephant, rhino and buffalo) could only be hunted with a .400 or larger caliber rifle and for hunting thin-skinned dangerous game (lion and leopard), a 375 Holland & Holland Magnum was the minimum caliber.

Theoretically, you can kill a lion with a 22 Long Rifle if the bullet is precisely placed to penetrate the brain from very close range, but it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to get within 22-caliber range of a lion under normal sport hunting circumstances. Consequently, more powerful cartridges are used to deliver the necessary velocities and terminal ballistics from greater distances.

The .375, classified as a medium-heavy cartridge, is perhaps the most universally accepted caliber for hunting the world’s big game, including most of the dangerous species. It’s effective out to 200 yards or more and allows some margin of error even at that distance. But its stopping power is marginal against Africa’s largest game—a role better suited to the .400 or larger caliber cartridges designed to penetrate thick skin, dense muscle and heavy bones.

Theories about which rifle/caliber combination best suits hunting dangerous game have fueled countless campfire debates and filled volumes of books and magazine articles. An animal’s size and disposition, as well as the type of terrain where it’s found, are key factors to consider when choosing a rifle/caliber combo with which to hunt. There’s no single gun or magic bullet that’s suitable for all situations and circumstances. A good basic rule to heed when hunting dangerous game is to use as much gun as would be appropriate for following that particular animal were it wounded—in other words, a rifle/caliber combination capable of stopping an animal in a determined charge.

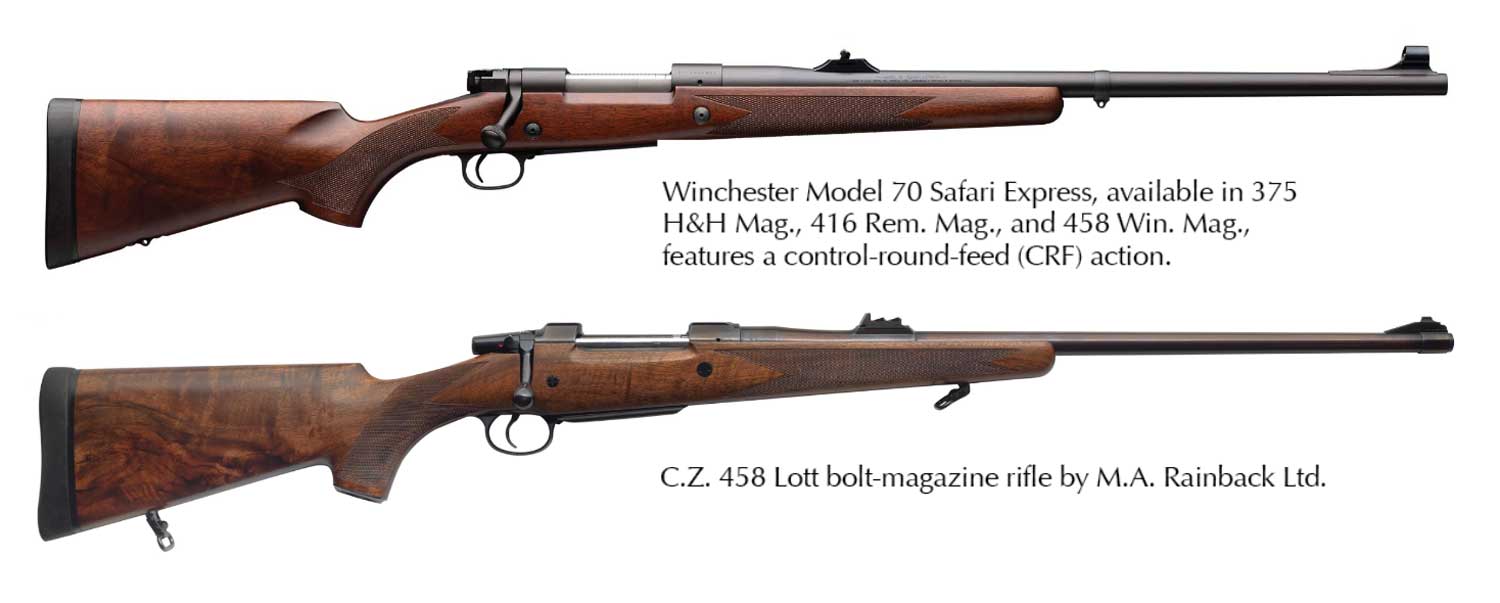

There are basically two proven platforms for big bore rifles that have yet to be improved upon in more than 100 years—that is the bolt-action, magazine rifle and the break-action, double-barreled rifle. These two rifle types are very different from each other, but they both provide the kind of accuracy and reliability required of a big bore gun.

There are basically two proven platforms for big bore rifles that have yet to be improved upon in more than 100 years—that is the bolt-action, magazine rifle and the break-action, double-barreled rifle. These two rifle types are very different from each other, but they both provide the kind of accuracy and reliability required of a big bore gun.

Double gun roots go back to mid-19th century when the 8-bore blackpowder double rifle was king and carried by intrepid British explorers such as Sir Samuel Baker and Frederick Courtenay Selous. During the earliest days of East African safaris, a double gun was the rifle of choice for white hunters. They firmly believed a double rifle’s dependability was based on the certainty of having two shots without cocking or reloading the chamber. That was as compared to a potential three or four shots from a magazine rifle, which required the manual cycling of the bolt for each shot. Double guns were the most commonly carried big bores by PHs up through the mid-1960s, at which time double gun ammo became difficult to obtain.

Achieving proficiency with a double rifle only comes from lots of regular practice. A skilled shooter can carry two spare cartridges between the fingers of the hand holding the forend for quick reloads and follow-up shots. The shortness of the action provides the advantage of having a shorter overall rifle length as compared to a magazine rifle with the same barrel length. Some might also say that it promotes better balance, although some double guns can tend to feel barrel-heavy. Those who are comfortable handling a double gun claim that it is quick to point and smooth to swing—important qualities when responding to the sudden charge of an animal.

Following World War II, the rising cost of already high-priced doubles and dwindling ammo sources caused many big game hunters to gravitate to the more economically priced magazine rifles and available ammo. Bolt-action rifles were considered to be stronger, more accurate and cycled ammunition more reliably in comparison to other repeating actions, such as pumps and lever-actions. They were also available in a larger variety of cartridges ranging from 22 caliber up through the 500 Jeffery and 505 Gibbs. The use of smaller calibers, not available in double guns, also promoted more practical and economical shooting practice.

Bullet choice for dangerous game guns is fairly straightforward—full-metal-jacketed bullets, commonly called solids, are used for the thick-skinned game while expanding bullets, or soft-points, are employed for thin-skinned game. Most of the old-school PHs believed in the exclusive use of solids for the thick-skinned dangerous game, and some even for the cats if they were hunting elephants at the same time. But their era did not benefit from the technological advancements in bullet construction that we enjoy today.

When it comes to buffalo, there’s varying opinion regarding whether to use soft-points or solids but, today, a good quality, controlled-expansion soft-point on buffalo is a viable first-shot option. Penetration is vital on heavy game, but there’s a good chance a solid will pass through an intended buffalo and hit another animal with side-on shots. A compromise is to employ a quality soft-point for the first shot and use solids for follow-up shots. For elephant and rhino, solids remain the only option.

But whichever rifle/caliber combination you use, proper shot placement is the key to eliminating the potentially dangerous follow-up that results from a poorly placed shot. That means that not only does the rifle need to be accurate, but the shooter must be able to shoot it accurately.

Essential Features

The late gunwriter, Finn Aagaard, a former Kenya PH, believed a dangerous game rifle should be strictly utilitarian. Aagaard wanted a rifle that was imminently portable—short enough for use in thick cover, but still with enough heft to steady longer shots. He wanted iron sights that worked from 15 feet to 100 or more yards and the rifle would have to withstand hard, rough service, but above all else it had to be reliable.

Aagaard described reliability as unfailing mechanical functioning. “It must go bang without fail every time the action is operated and the trigger pulled,” he wrote. “But, reliability also includes consistent grouping ability and the dependable maintenance of zero.”

His choice of action for the ideal big bore rifle was the Mauser Model 98, which combined reliability with accuracy. Aagaard was not alone with his opinion, as most knowledgeable shooters still believe the Mauser M98 to be one of the finest, if not the finest, action for a big game rifle ever designed. Included among the M98-style actions are Winchester’s pre-’64 Model 70 action (currently available in post-’94 production), the Model 1903 Springfield and the vintage Czech-made Brno ZKK 602 magnum-length action. These actions employ a non-rotating claw extractor for positive feed and extraction, and they are plenty strong to handle the heaviest calibers.

Some perceive as a fault that the M98 bolt only picks up and feeds cartridges from the magazine. You cannot drop a cartridge directly into the chamber and close the bolt over it because the extractor will not normally snap over the rim of the cartridge. It’s possible to alter the extractor by changing the bevel on the front face of the hook so that it will snap over a cartridge rim, but this is very tricky to do without shortening or weakening the hook, and thus compromising the gun’s reliability. If this type of alteration is attempted, it should only be done by a very competent gunsmith familiar with the alteration.

John “Pondoro” Taylor, noted African hunter and author of African Rifles and Cartridges, stated in no uncertain terms that he was opposed to any alteration of the original Mauser bolt design. “Personally, I consider it an exceedingly dangerous habit (loading directly into the chamber), and have repeatedly said so…” he wrote. “Not only do you run the risk of breaking your extractor without knowing that you have broken it, which would result in your being unable to fire a quick second shot should you want it, but there is also a very real risk of giving yourself a dangerous jam in a tight corner.”

When judging the merits of a particular bolt-gun for work with dangerous game, consider first and foremost the smoothness of action in order for the bolt to work quickly and reliably. Placement, position and angle of the bolt handle all determine how accessible it is—again, important for rapid cycling of cartridges. Concerns about the distance of bolt travel on magnum-length actions should be secondary to smoothness of action.

A professional hunter’s rifle almost always sports iron sights, either with express-style, shallow-V blade-sights, or an aperture-style peep sight. Iron sights are sturdy, almost damage proof and completely weatherproof. An aperture sight with a large opening, referred to as a “ghost ring,” is possibly the fastest sight of all. But whichever type of sight is used really becomes a matter of personal preference.

Scopes generally offer little advantage during close work in thick cover and can be a hindrance by snagging on brush, but sport hunters who are accustomed to using a scope often fit their rifles with variable scopes that offer magnification from 1X to 10X. Scopes with 10X or stronger magnification are unwieldy and difficult to hold steady without a firm and solid rest—not always available during hunting circumstances. In Africa, the use of three-legged shooting sticks, commonly carried by a tracker or the PH, provide a rest for the rifle and help steady the shot. Another compromise to using a scope is to mount it with quick-detachable scope rings. This allows you to easily remove the scope in the event of a follow-up in thick bush.

The position of safety catches varies from sliding, tang-positioned safeties to Winchester’s M70-style wing safeties located on the back of the bolt sleeve. Mauser’s three-position leaf safety rotates laterally 180 degrees across the back of the bolt. All of these safeties are efficient but require complete familiarity and awareness to master flicking them off as the rifle is engaged to take a shot.

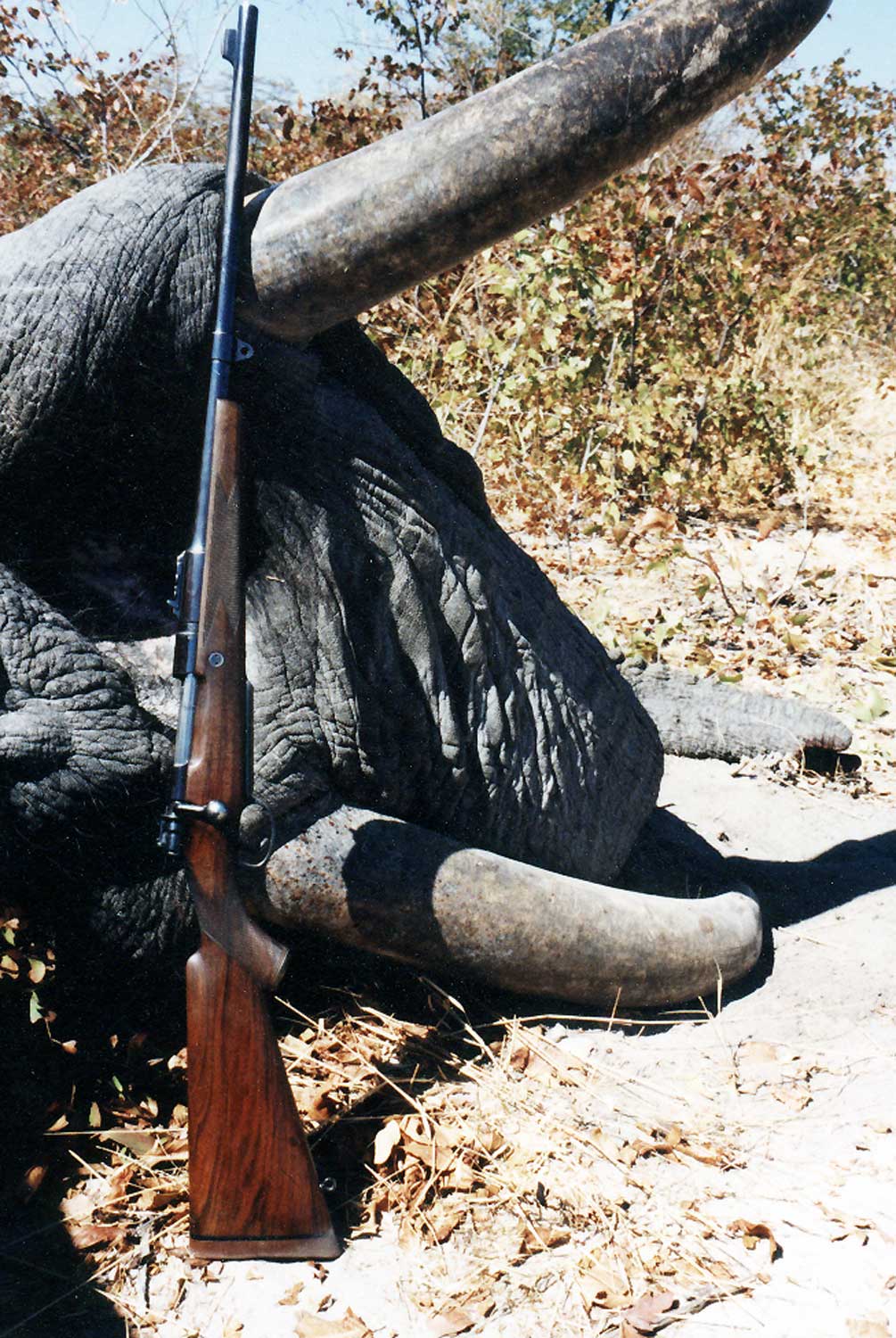

Harry Selby acquired his 416 Rigby rifle in 1949 and carried it for more than 50 years of safari hunting.

My first big bore rifle was a Winchester Model 70 “African” chambered for the 458 Winchester Magnum cartridge. My father bought the rifle in Nairobi in the late 1960s at which time we were Kenya residents and were licensed to hunt buffalo, lion and elephant with it. I began professional hunting in Botswana with the same Model 70, .458 and used it for many years. I did have a very competent South African gunsmith fit a quarter-rib and express sights and a barrel-band front sight to the rifle, which improved the sight picture and gave the rifle a classic “big bore” look.

Later, I acquired from Harry Selby, another .458 rifle built on a Mauser M98 action that assumed the heavy-weight duties that the Model 70 had reliably accomplished. During the years I carried those .458s, neither the rifles nor the caliber ever let me down.

Considering that an animal is only dangerous when at close quarters, it’s imperative that a dangerous game rifle shoots exactly to point of aim at close range and functions flawlessly in the heat of the moment. Long before an aspiring hunter attempts to hunt dangerous game when he might have to brain a charging elephant, or down a Cape buffalo at 15 paces, he should be so familiar with his rifle that it comes up as quickly and as naturally as pointing his finger.