“But there was something there — a different kind of contemporary realism.”

Imagine for a moment that you and I are with artist Adriano Manocchia, relaxing on Adirondack chairs under the eave of the porch at his house in Cambridge, New York, a double haul from the Vermont border.

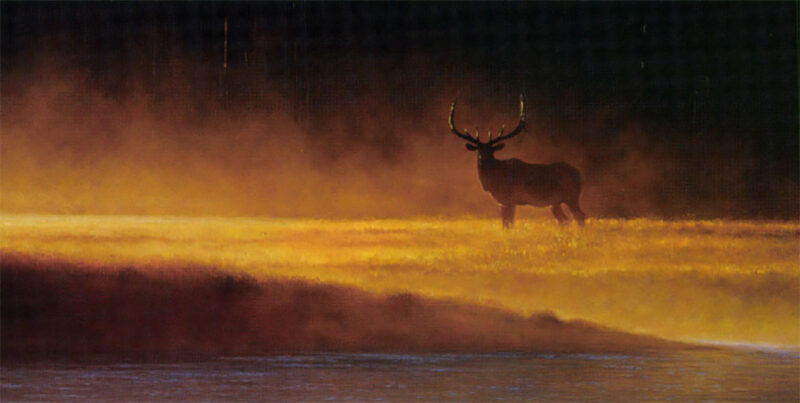

We’ve just come out from his studio. Inside, he just added a layer of color to a painting of his favorite reach of the Firehole, which is upstream from Yellowstone’s Middle Geyser basin. Set in September, looking downstream, one sees the mud pots and fumaroles that scent the air with brimstone. To the right, a train of bison ambles down from the height at Muleshoe bend. The low ridge and the meadow are bathed in sun, yet to the west in the direction of the Madison, the sky carries a deep grey-blue patina, the color of the barrels on that old Parker that stands muzzle-down in my closet. A front is in the offing.

We’ve just come out from his studio. Inside, he just added a layer of color to a painting of his favorite reach of the Firehole, which is upstream from Yellowstone’s Middle Geyser basin. Set in September, looking downstream, one sees the mud pots and fumaroles that scent the air with brimstone. To the right, a train of bison ambles down from the height at Muleshoe bend. The low ridge and the meadow are bathed in sun, yet to the west in the direction of the Madison, the sky carries a deep grey-blue patina, the color of the barrels on that old Parker that stands muzzle-down in my closet. A front is in the offing.

You and I have fished that run of the Firehouse often. The rainbows there have humbled us many times. Adriano, too.

“Fishing the Firehole can be a religious experience,” says the talented artist. “Whenever we go out there we spend at least one morning or one sunset on that stretch.” Often, he and his wife, Teresa, will just walk along the river, captured by the tableau before them and the water at their feet.

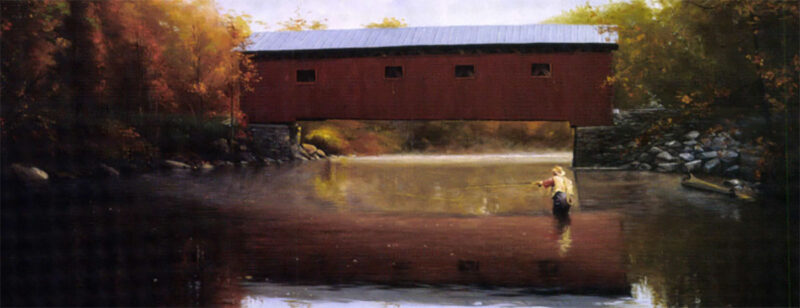

Ask most art dealers who know his work and they’ll tell you that one of Adriano’s fortes is painting water. If you don’t believe me, look closely at the stream in About to Test His Skill. You’ve seen water just like this wet you’ve waded the Battenkill, the Au Sable, the Gibbon in the meadow where browns are suckers for hoppers or in a hundred other streams where you fish.

“When I’m paining water, I paint in layers,” he explains. “I’ll lay down a coat of color and let that dry. Then I’ll go over it. My water sometimes has three, four, five layers of color, which helps me get that look and feeling of depth.”

Exactly! All of us who’ve cast a dry fly know the microcurrents that frustrate our drifts. A stream is filled with layers of water, each moving at a slightly different speed and direction. Each current refracts light in a manner just a bit unlike the current next to it. Refracted light makes water shimmer. Into his water Adriano paints currents.

Flowing along the edge of the Manocchia’s 38 acres is a little stream, the Owl Kill. It’s rich with native brookies. When he bought the house in 2004, Adriano cast Hendrickson’s to them in the spring, tried them with ants in the height of summer and drifted weighted pheasant tails for them after they’d spawned in late October.

Now, content just to know the brookies are there, he leaves them alone and casts his flies on more distant waters. He haunts the Battenkill and chaired its conservancy, advocating for more watershed education in schools. You’re apt to find him on Catskill streams, on famed runs of Colorado’s Gold Medal Waters, after steelhead in British Columbia or bonefish in the Bahamas. For decades he’s fished only dries, but now he’s throwing Matuka streamers for big browns. When he tells me this, I welcome him to fly-fishing’s dark side.

“One of the most gratifying things is when I hear a fly fisherman whose seen one of my paintings call up and say: ‘Man, I feel myself being on that stream. I can just feel the mist coming off the water, can feel the cool breeze.’ To me, that’s the greatest reward,” Adriano says, “because I know I’ve expressed something I’ve felt on a river and another fisherman is feeling the same thing.” On one hand realistic and on the other, romantic, Adriano’s angling fit is indeed compelling.

Late in the Angler’s Season

Adriano Manocchia is blessed with a knack for color and composition. Apparently, it’s in his genes. When he was a boy, his family lived in New York City, where his father was a foreign correspondent for Italian television and several major periodicals. Adriano’s fascination with images began one Sunday afternoon when he was in his mid-teens.

“My dad was going to Yankee Stadium to cover a soccer match between Brazil and Italy. The great Pelé was playing for Brazil and my dad asked me if I wanted to come along.

“Here I was, a kid born in New York, and all of a sudden I get to go stand on the field at Yankee Stadium. ‘Yes, I’ll go!’ I told my father.

“Before the game began he handed me an old Rolleiflex and said, ‘Do you want to try taking some pictures?’ I took a couple of rolls and never thought anything of it. A couple of weeks later, a bundle of newspapers arrived from the Italian daily my dad worked for. Here was this article about the soccer match at Yankee stadium and a black-and-white photo of Pelé kicking a ball.

Adriano remembers telling his dad, “that’s nice,” then glancing away until his dad suggested he look again at the name under the photo. There was the credit line: Adriano Manocchia.

“It was like an adrenaline rush,” Adriano beams at the memory. “It was one of the pictures I’d taken!”

As a teen, Adriano had a passion for cars. Still does. Just ask him about the 1970 Porsche in his garage that he’s restoring. It was only natural that he’d combine his affinity for photography and cars. “I started shooting a lot of auto racing around the world and sold my photos to magazines in Italy and Germany and England.”

Adriano’s photo freelancing paid for college at Pace University and sent him forth on a career first as chief photographer for the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union. He continued to freelance for the European news media. In Rome in 1970, he met Teresa and they were married three years later. The couple had a son, Adriano Jr. and moved to New Rochelle where he toiled almost around the clock as a freelance photographer. He shot footage on the Nimitz, photographed President Carter and other luminaries ranging from Tennessee Williams to Muhammad Ali. An assignment here today, another there tomorrow. “Beyond hectic” is how he recalls that stage of his life.

Edge of the Forest

In the early 1980s Adriano arrived in Phoenix to cover an Indy car race. “Teresa was with me. We had some time off and we ended up in the Heard Museum. I got to see the Cowboy Artists of American show, and it blew me away to see what the artists were painting. Right then, I decided that painting was something I really wanted to try.

“We came back to New Rochelle and after a couple of months we shut down the photo agency and I started to paint. It was totally insane!” he laughs. “I would never consider something like that now.”

For the next few years, he closeted himself in libraries, reading about art and drawing, and painting with watercolors and oils. Eventually he started sketching and painting wildlife in the field. “Don’t ask me why I chose wildlife — I just gravitated to that subject,” he says.

Within a few more years, Adriano was elected to the board of directors for the Society of Animal Artists. One is not chosen for that honor unless one is pretty damn good. Still, his art sales began oh-so-slowly.

“An acquaintance of mine, Craig Kessler of Ducks Unlimited, asked me to participate in a wildlife art show at Hofstra University,” Adriano remembers. “It was on Thanksgiving weekend and most folks were at the mall shopping. Only a handful of people had come through our exhibit by late Sunday afternoon.

“It was a quarter-to-five, just about closing time and I was pretty unhappy because we’d just spent three days twiddling our thumbs. I wanted to go, but Teresa insisted that we stay until five o’clock.

“While we were waiting, a man and woman walked up to our booth. They spent a few minutes looking at my oil painting of a Harris hawk. They were taking their time and at this late hour I was saying to myself, Oh come on, these people aren’t going to buy anything.

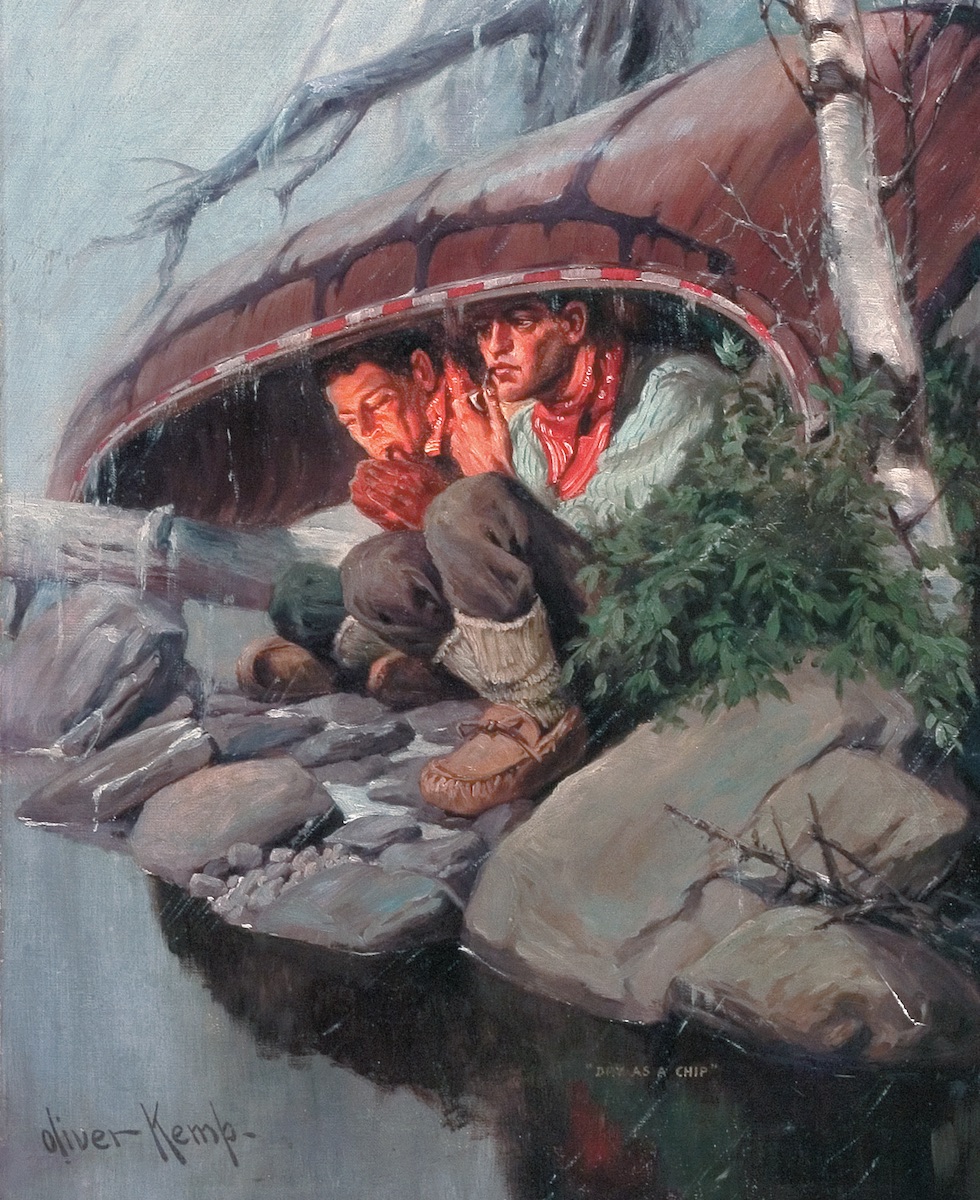

In Summer Storm

“The couple left our booth and went to look at the other exhibits. It’s now five o’clock and I’m ready to get out of there, but to my surprise they came back and started looking at my painting more closely.

“After studying the painting for a few minutes, the man said — and remember, this is about 25 years ago — ‘How much is this?’

“I told him the price was $600.

“He said, ‘Can you do any better?’

”You know, I hadn’t sold much in weeks and I figured it would at least pay for the gas to get home. So I sold him the painting for $400 and he hands me his business card along with the money. I had no idea that we would soon become very dear friends and through the years he would become one of the biggest collectors of my work. We’ve gone to Alaska together and the Bahamas fishing, and he and his wife are super, wonderful people.”

The man who bought the painting was John Dreyer, whose extensive collection includes works by John Singer Sargent, Pendergast, Ogden Pleissner; Winslow Homer, Frank Benson, A. L. Ripley and a large number of Adriano’s oils.

Season’s Almost Here

John Dreyer likens Adriano to Frederic Remington. Not that Adriano’s work is similar in style or subject matter to Remington’s. It isn’t. Remington started as a magazine illustrator, but as he grew older, his work matured and he became less an illustrator and more a gallery painter. Dreyer sees Adriano’s paintings becoming less photographic and more painterly.

So does another John in Adriano’s entourage of good friends. This is John Apgar, former director of the J. N. Bartfield Gallery in Manhattan. Five years after putting aside his cameras and picking up his brushes, Adriano came to the gallery on 57th Street to show his work.

“His sense of composition and his colors were good, although he still needed maturity as an artist,” Apgar recalls. “But there was something there — a different kind of contemporary realism.”

Over the past two decades John Apgar has seen Adriano’s work evolve. “His designs have more depth and his contrast using the darkest dark against the lightest lights are more dynamic and add to the strength of his paintings. His personality is definitely into his paintings.”

“So many of today’s wildlife and western artists are painting things they never experienced,” Apgar continues. He says that many find a style that resonates in the art market and then paint that way for their entire careers. Adriano, however, insists that such a philosophy would impede his personal growth as an artist.

“What’s so exciting about coming into the studio and painting the same scenes over and over again?” Adriano questions. “To me, the excitement is starting that next painting, pushing the design, the composition, the color movement and trying to keep progressing to the next level.”

Indeed, Adriano Manocchia exists in a state of perpetual growth. “The maturing process is a slow one,” he says. “I’d like the process to go faster but I don’t think you can push something like that . . . it has to come when it’s ready.”

“What makes Adriano special,” John Apgar adds, “is that he takes guidance. He’s always experimenting — pottery, etchings, watercolors, oils — looking to better his work. In the past few years, he has introduced more color moment and spontaneity by using an economy of brushstrokes. The fewer the strokes, the fresher the painting looks. An artist today might take 40 strokes to paint a button on a blouse. On the other hand, a portraitist like John Singer Sargent would use only a few strokes.

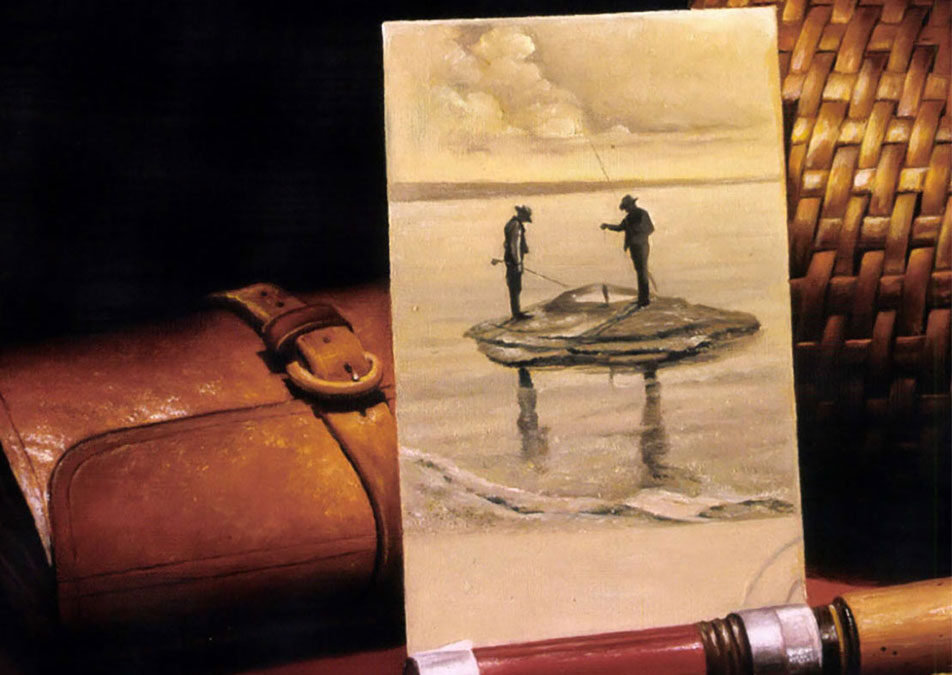

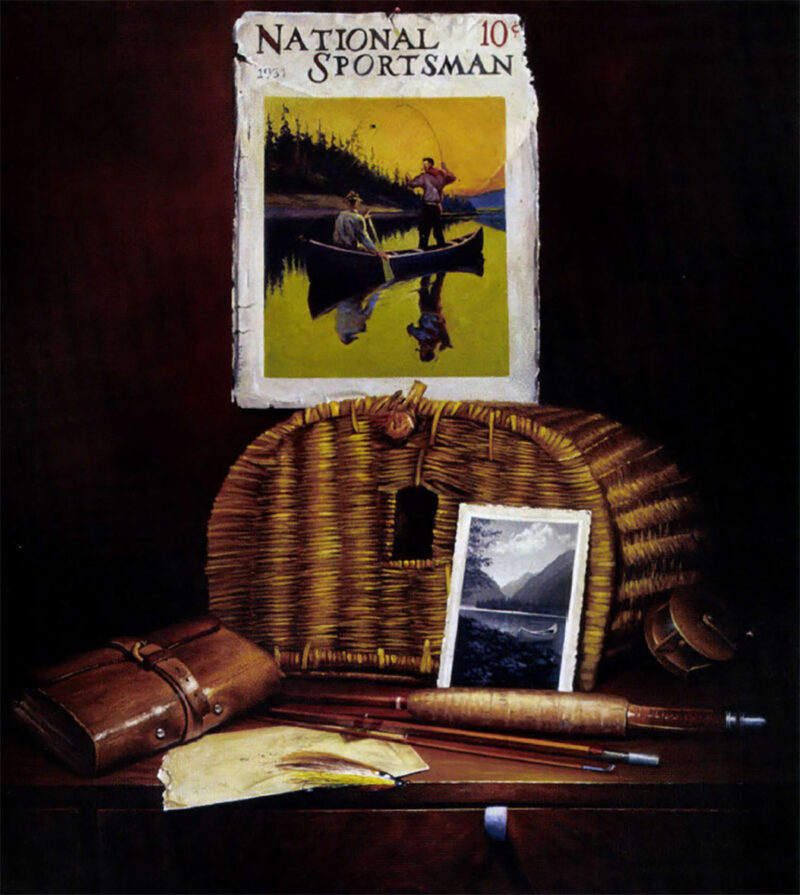

As I study Adriano’s paintings, I find that his still-lifes resonate deeply. Look at Season’s Almost Here. I can smell the neat’s-foot oil that’s been rubbed into the leather of the leader wallet to soften it and the mustiness of the tattered cover from National Sportsman. The wicker creel and cane rod could have been owned by your grandfather or mine, had they been fishers of streamers like the Grey Ghost lying on the faded letter.

About to Test His Skill

“Adriano is the foremost artist doing sporting still-lifes today,” notes Apgar. “He’s the only one doing them of any notability, and his landscapes are blooming into his own unique style of contemporary realism.”

In all of Adriano’s paintings — of landscapes, still-lifes, anglers, golfers and wildlife — I sense a tranquility, the same thing I’d see if we strolled into his back field, past the dark red carriage barn he’s slowly converting into a studio, toward Owl Kill where the native brook trout swim.

The bucolic aura that surrounds his work belies his steely pursuit of the craft. A passion, sure, but make no mistake, it’s also work. Underway are five or six paintings, some waiting to dry, others ready for the next step of inspiration. His innumerable achievements and exhibitions over the 26 years he’s been painting testify to his prolificacy.

During our long-distance conversation, I comment that he seems intensely entrepreneurial and driven, almost like a top-ranked athlete. I can almost feel him leaning forward in his chair.

“I get annoyed when I hear people saying: ‘Well, why are we giving $50 million to the National Endowment to the Arts? The arts do not give anything back to the economy.’ I guess it goes back hundreds of years . . . that art was not supposed to be a business, just a creative process.

“But I put my son through college with my art. I bought a house with my art. I had to support myself with my art and feed my family with what I do, and that’s painting. So why am I not supposed to make a living at it?

“When I was doing photography and filming, I had deadlines, I had commitments, I had assignments I had to fulfill. I’d take off and fly to L.A. one day, get back on the plane and fly to Seattle the next and shoot another job and fly down to Arizona and shoot a job and come home and make sure all that work was sent out in time for the magazines and TV stations.

“So to me, there was always that nine-to-five, this is a commitment, this is a job. I approach my painting that way. I get up in the morning and I’m in the studio at eight and I’ll paint till six. I enjoy playing with my antique cars and I go fly-fishing a lot. Still, I’m very disciplined in my approach to painting.

“I just don’t buy this ‘Well, I can’t paint today because I’m not creative or don’t have that inspiration.’ I could never buy that — maybe it’s just me. I guess we’re all different,” he laughs.

“I usually have a number of images going at the same time. By doing that, I might walk into the studio and see something with a fresh eye and say, That buffalo or fisherman isn’t in the right place and I’ll make changes. Or, there might be a painting that’s been sitting in the studio for a week or a month and I haven’t touched it, and I’ll walk in one day and everything just clicks. I’ll say, ‘I see it, I see what I need to do.”

Past Treasures (detail)

Most of Adriano’s paintings progress in distinct stages. “After I’ve done a couple of thumbnails and looked at some old sketches from a trip, I’ll decide on a smooth board covered with gesso. I loosely block in the painting using burnt sienna, white and ultramarine blue. This gives me an idea of composition, a feel of the darks and lights. At that point, if I see something is wrong, it’s very easy to “wipe it off, go back and re-sketch. Then I’ll put the roughed-out painting aside and let it dry for a couple of days, and after that I’ll start putting in color.”

In likening Adriano to Remington, John Dreyer and John Apgar both lamented that Remington died in his 40s, when his work was beginning to mature into impressionism. John Apgar talks about the progression of artists’ styles. He believes that Remington, had he lived into his 90s like Picasso, would have become a notable impressionistic painter of world class. There’s no doubt in Apgar’s mind that Adriano is destined to eclipse the boundaries by which angling and wildlife art are now defined. I can only wish that you and I are still around to see him do it.

As exhibited in this section of 150 paintings and in Langmead’s absorbing and enlightening text, The Light Fantastic is a transcendental journey, a 20-year love affair between the artist and the beauty of the natural world. For those who have fallen under the spell of the unspoiled wilderness, and those who yet dream of new journeys, wether they be wildlife enthusiasts or travelers, this is a book to treasure.

As exhibited in this section of 150 paintings and in Langmead’s absorbing and enlightening text, The Light Fantastic is a transcendental journey, a 20-year love affair between the artist and the beauty of the natural world. For those who have fallen under the spell of the unspoiled wilderness, and those who yet dream of new journeys, wether they be wildlife enthusiasts or travelers, this is a book to treasure.

The Light Fantastic invites you on a journey into the secret heart of the African bushveld and beyond. Traveler and artist David Langmead has returned time and again to his favorite wilderness areas in passionate pursuit of their sensual beauty. Buy Now