Billfishing was the perfect pursuit for a man endlessly intrigued with saltwater watching.

Saltwater at first sight was Al Barnes’ epiphany. Its many manifestations dazzled the boy newly arrived at the fishing village of Port Isabel on the Texas Coast and became the essential medium for the man who would emerge as a respected painter of the outdoors.

The artist

And such waters there were to captivate his eye and mind with mesmerizing movement and a palette of glowing colors: Indigo blue on the horizon of the endlessly rolling Gulf of Mexico. Emerald and lace where the breakers beat on the beaches of Padre Island. Gold over the green seagrasses in the shallow Laguna Madre. Coffees and teas in the steamy brackish marshes.

Riding over it all was the endless play of sunshine and sea breeze casting highlights of rose petals and pennies, diamonds and jewels. Don’t forget the shafts of light through the water column or the shadows cast over the bottom, Barnes the artist would politely add.

And you won’t either if you see the paintings that truly reflect his artistic vision.

“I love to paint water; nothing excites me more,” he enthuses. “Most of my paintings start by just trying to depict how light and water react – what happens when the sun strikes the surface at a certain angle or what a passing cloud formation creates.”

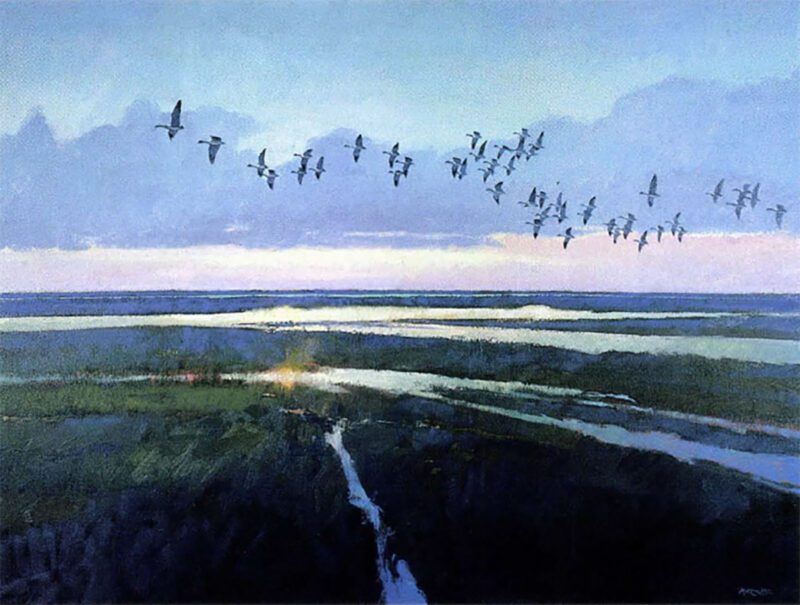

Trailing Blue, a painting from his “Bluewater Period” of the ’80s.

These carefully considered words represent a long speech for the 59-year-old artist, whose manner is soft-spoken and self-effacing. Yet they also describe the elemental reality of an artistic style that evolved with Barnes’ ever-expanding watery horizons to earn him numerous awards and honors for his depictions of hunters and fishermen in beautiful seascapes.

But five decades ago, the dazzled youngster would settle for nothing less than full immersion in his marine environment, first as a wader of beaches and shorelines, and later as a sailer and angler of the sprawling lagoon and a hunter of the marshes. “I was always on the water,” he says in his usual understated manner.

Well, not quite. When experiencing his water world wasn’t enough, Barnes began sketching and painting it with an innate skill that attracted attention in a small tourist town and enabled the youngster to buy more freedom to enjoy the great outdoors.

At age 11, he sold his first paintings for $3 a piece to grace the walls of what in those days was called a “tourist court.” During his high schoolyears, Barnes split his spare time between being on the water and sketching and painting sets, signs and advertising art for a local television station. Then, he was off to the University of Texas in Austin to earn a degree in art and pursue a career in commercial advertising. But Barnes remained enthralled with coastal waters and couldn’t wait to show them to bride-to-be Nancy Schabbehar, a student artist with talent in painting and pottery.

“The first time Al took me down to Port Isabel, we wen tout in this little sailboat that seemed on the verge of sinking,” Nancy remembers. “That’s when I realized he had this fetish for boats that would always insure us a self-draining bank account.”

Broken Calm

Barnes’ years as a commercial artist led him from Texas to New York and back to Texas. The late ’60s found him and Nancy landlocked in Dallas, where they were struggling artists trying to support two young sons, a small boat and a shack on the Texas Coast near Rockport. That’s when Barnes came to the proverbial fork in the road of life and took the one less traveled.

Nowadays, he will say his art has been influenced by the works of Claude Monet, William Chase and John Singer Sargent. But there was a more immediate influence at the end of the ’60s. It was the publication of The Golden Crescent, a large and beautifully rendered book featuring the paintings of Texas artist Jack Cowan and the fishing and hunting stories of noted Texas writer Bob Brister.

“I was amazed with the book and Cowan’s art. I studied it over and over for a year and tried my hand at similar paintings,” Barnes admitted. What he saw above all was an artist who had forged a successful career painting fishermen and hunters on the cactus uplands and sprawling marshes of Texas. “Cowan was a big inspiration for me at the time. I even called him up once, but I was so nervous I hung up when he answered the phone. Now, of course, we’re good friends.”

In 1970, Barnes made the fateful decision to buy a home in the seaside community of Rockport and become a fulltime painter. Not even Hurricane Celia’s destruction of the family cabin deterred him from making the move. At first, he painted what he thought would sell, whether landscapes of the Texas Hill Country or waterscapes associated with fishing and hunting. He was averaging two paintings a week, most of them oils rendered with the aid of photographs, sketches and watercolors produced in the field and backed up by a lifetime of vividly remembered hunting and fishing experiences.

For those who wonder how an artist and his art come together, there was and remains something curious about Barnes’ collection of field photographs and sketches. Take his fish photos, for example. They tend to focus on detailed studies of eyes, fins, scales and tails, as well as poses of fish in various attitudes of swimming or striking. Missing are panoramic photographs to be meticulously rendered on canvas.

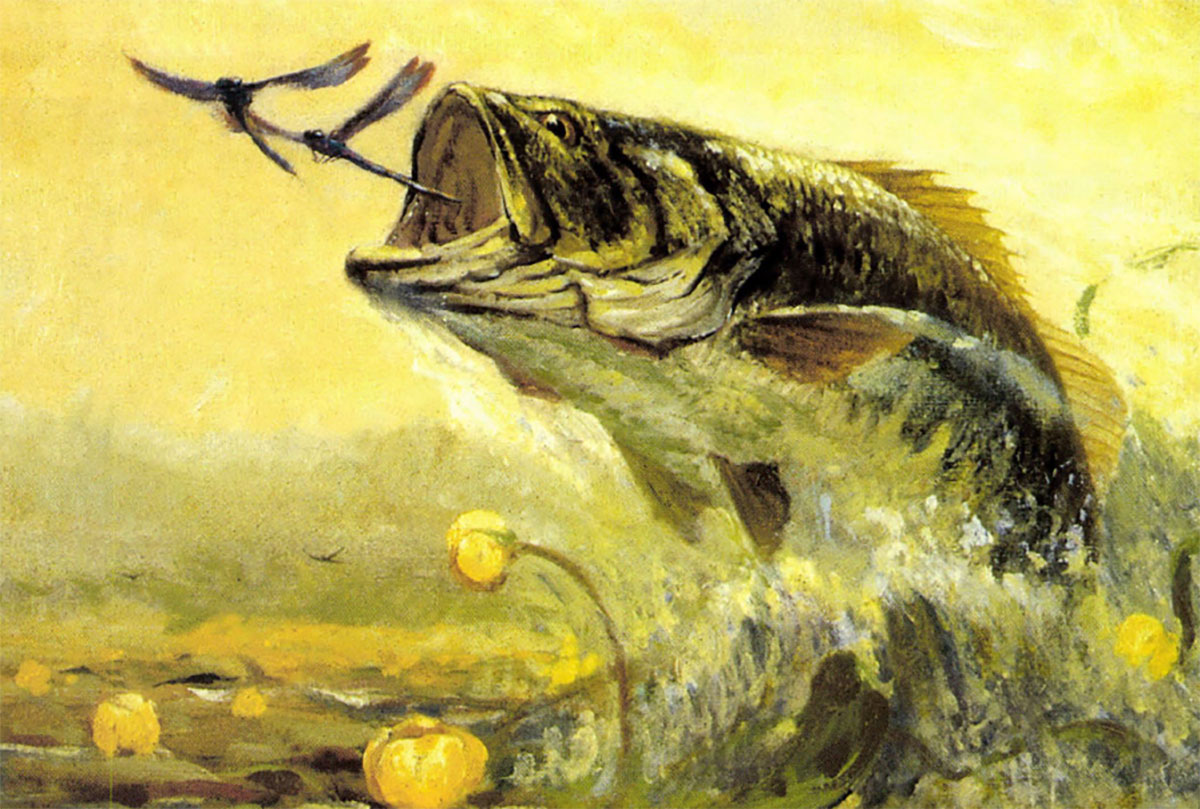

In Knockdown and other paintings of billfish, Barnes says he is challenged to take the monochromatic blue of the ocean and give it depth through shadings of color and light, and the positioning of fish. Adding bubbles and foam implies turbulence in the water, which brings motion and life to an underwater scene.

“I know artists that spend weeks or months on a painting, getting it so tight it squeaks. I admire their patience, but for me, I want to see paint on canvas, a confrontation between artist, idea and medium, (while)always keeping in mind that I am painting a painting, nota photograph,” Barnes explains. He noted that this same approach shows up in the works of Bob Abbett, Tom Daly and Stanley Meltzoff, all admired contemporaries.

By 1977, Al and Nancy had purchased a lot in a shady grove of large live oaks and had built a modest, two-story, board-and-batten home they still occupy today. Construction of his and hers studies soon followed, as did the addition of a boat shed.

Barnes was on his way to prominence among Texas’ contingent of wildlife artists, though he didn’t wear the mantle easily. “I never really considered myself a wildlife artist; rather, an environmental painter. Paintings that show action such as birds being shot or fish being caught are events that take place in a very small time-frame. I’m more interested in the arena where the event occurs.

“In my paintings you have a lot of time to look around. Rarely does something happen in a split-second to draw your attention from the overall scene,” he says. “The birds, fish and people are simply bit players depicted in a scale that doesn’t detract from the most important part — the overall panorama.”

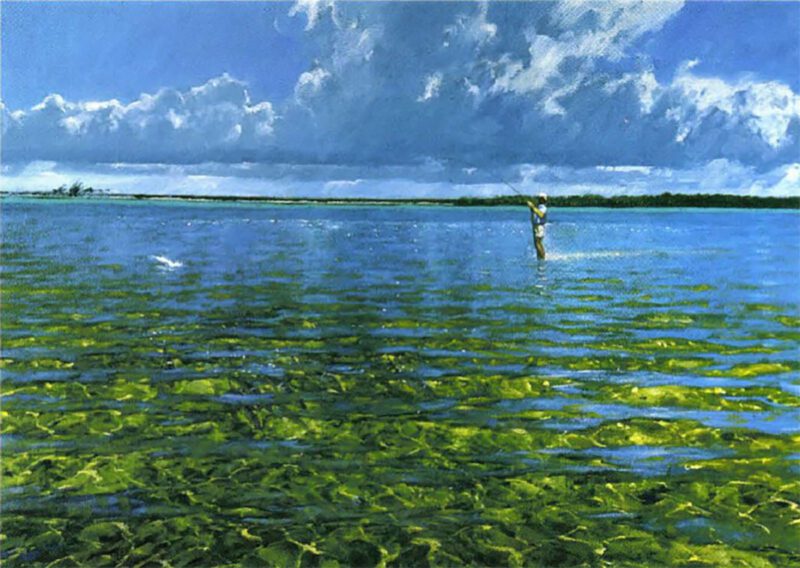

Out of the Pack conveys the luminous colors of a sun-drenched flat, where a lone fisherman duels one of the silver phantoms.

Barnes mentions an example. “I once did a duck hunting piece titled Opening Day, which depicted a bluebird morning in the marsh. There was a single duck blind, but not a bird in sight because that’s the way it was … just one beautiful morning.”

Therein, perhaps, lies the appeal of his art among many Texas anglers and hunters. Fishing and waterfowling involve long periods of waiting and watching intermixed with short, sporadic bursts of action. While sportsmen may always hope for fish on the line or birds over the decoys, it is a heartfelt connection with the natural environment that keeps them coming back again and again.

Barnes’ paintings set in Texas coastal waters made that connection with imaginative if not emotional power. “I paint the experience of being there, to capture the familiarity of being there,” he says. But as his colorful depictions of Texas settings became more popular, Barnes thirsted for more in the form of new waters and new challenges. He became a bluewater billfish angler.

The quest for sailfish and marlin took him beyond the horizons of the Gulf of Mexico to the Atlantic and Pacific. He ranged as far as the waters around Hawaii and off Peru. Today, photographs of successful conquests of big marlin clutter the walls of his studio.

Billfishing was the perfect pursuit for a man endlessly intrigued with saltwater watching. “You sit there on the boat, trolling for days and days with nothing happening, watching the lures and the water, imagining what it’s going to be like when a fish appears,” he says.

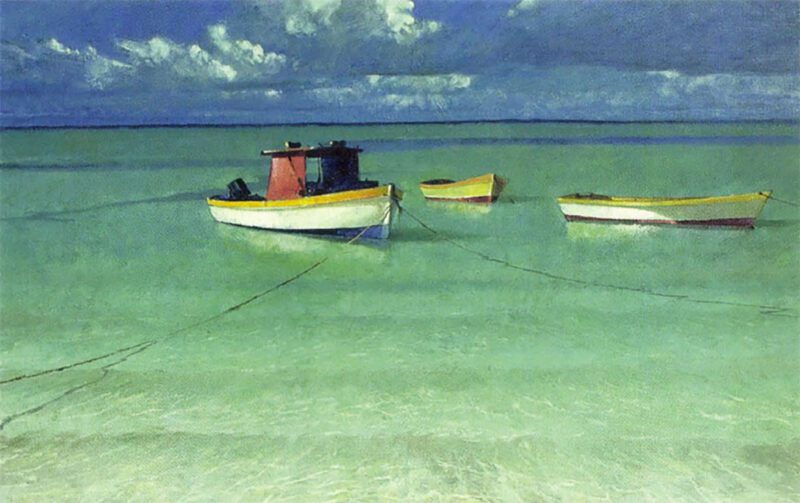

Isla

One particular vision , however, reached beyond imagining to the realm of the truly awesome. It happened almost a decade ago off the Kona coast of Hawaii where Barnes had joined a large party of Texas fishermen for a marlin tournament. The artist and Erik Doughty of Corpus Christi were aboard a 36-foot sport fisherman named the Hoolili, which in Hawaiian means “The Wake of a Great Fish.” It was an appropriate name for what was to transpire.

“They hooked a blue marlin estimated at more than2,000 pounds,” recalls bluewater outfitter Ron Young of Corpus Christi. “I believe Doughty was the one with the rod, but they fought this huge fish most of the day. Three or four boats gathered around to watch the fight and everybody saw the fish. They managed to get flying gaffs into the monster three times,~ but the fish straightened out each one. About the fourth or fifth time they had the marlin up to the boat and the line broke. Talk about the big one that got away ….

Needless to say, the artist didn’t lack for inspiration during his “Bluewater Period” of the ’80s.

Barnes painted Early Flight in 1996, when he was named Texas Ducks Unlimited Artist of the Year for the second time. He has also been honored as National Artist of the Year for DU.

Barnes’ billfish paintings brought him greater recognition in publications associated with bluewater angling and increased sales of his art in a market that rapidly expanded to the West Coast, Europe and South America. Along with his increasing popularity as an artist, he became a philanthropist for the cause of marine conservation. For years Barnes has made an annual practice of donating original paintings to Ducks Unlimited, the Coastal Conservation Association, and International Gamefish Association. He has signed more than 10,000 prints for DU and 8,000 for CCA chapters. One print edition raised more than $700,000. Suffice to say, Barnes’ generosity has meant millions for marine fish and wildlife.

Over the years, Al Barnes has been unrelenting in his quest to stretch the limits of his art. By the time the popular milieu of underwater art was attracting many imitators, he was already looking for fresh waters to stoke his imagination. In the early ’90s he found them in the Caribbean, which he now describes as his “favorite part of the planet.” Specifically, he is enthralled with the pristine bonefish flats surrounding tropical islands.

“Painting flats fishing, flats scenes and tropical situations is where I expect to be going with my art over the next 10 years,” he reveals.

Barnes, [at the time, was] coming up on 60, and presents a grandfatherly figure with a thick shock of white hair, a friendly, open face, and a low-key, humble manner. That’s good, because the Barnes homestead is on a well-beaten path in Rockport where birdwatching and art appreciation are major interests. The fountains and native plants under the live oaks in his sprawling yard attract a large variety of birds, which in turn, attract bird-watchers. Barnes has become accustomed to looking up from a painting to see birdwatchers in the yard or to hear art enthusiasts knocking at his door. He accepts the interruptions with patient good humor.

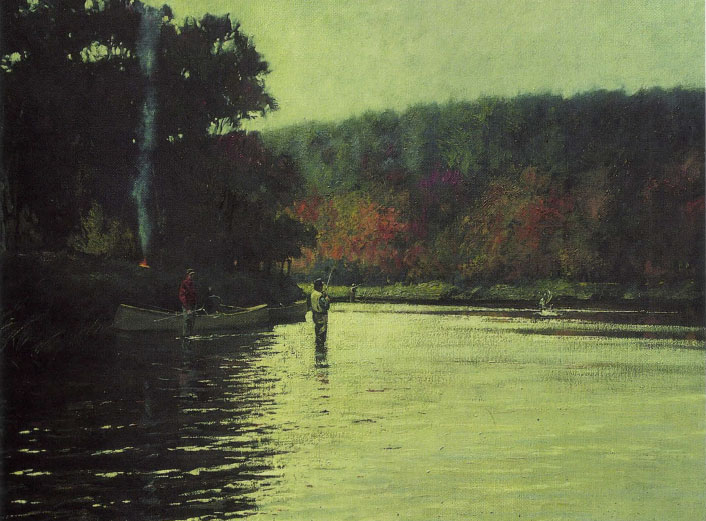

Barnes has painted a variety of fishing locations over the years, among them Manuel Pool, an autumn scene of Atlantic salmon fishermen.

Barnes the artist says he intends to slow down a bit, cutting back to between forty and sixty paintings a year. Forty to 60? That’s two to three times what many established artists regard as a major yearly output. But as Barnes notes, “I’ve always admired what (William) Chase told his students: ‘Take as long as you need to finish a painting, even if it takes 20 minutes.'”

But this slower pace apparently doesn’t mean less time on the water.

As this [was] being written, Barnes [was] aboard his 36-foot trawler Cheers, working his way toward the Caribbean for an extended stay of cruising and fishing, painting and just plain water-watching. As the largest power boat in the veritable armada that he’s owned over the years, Cheers has live-aboard capability to allow for sojourns of several months’ duration. The trawler also has paint aboard capability, allowing Barnes to use it as a floating studio with the sun above and the water a few feet below. The merging of artist and his medium can’t get much closer.

His is a classic case of life imitating art. Or is it the other way around?

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 1997 May/June issue of Sporting Classics.

This strikingly beautiful, large-format book showcases Guy Harvey’s around-the-world fishing and diving adventures. Drawing from meticulous notes, knock-out photographs and Guy’s signature artwork, Guy weaves together fascinating stories, scientific discoveries and insights into the behavior of dozens of gamefish species to give us an up-close picture of his time on and in the water. Buy Now

This strikingly beautiful, large-format book showcases Guy Harvey’s around-the-world fishing and diving adventures. Drawing from meticulous notes, knock-out photographs and Guy’s signature artwork, Guy weaves together fascinating stories, scientific discoveries and insights into the behavior of dozens of gamefish species to give us an up-close picture of his time on and in the water. Buy Now