This is an excerpt from an article that originally appeared in the August 1910 issue of Outing magazine.

This day we were in the heart of moose country with an ideal landscape spread before us, glowing with the golden red of a northern sunset. I worked quickly, absorbed in the glory of color across the bog as the sun dropped to the far-off western rim of the forest. Everything on the marsh—the juniper clumps, the white birch saplings, the bleached stumps—took on a palpitating stain of rose. In the forest where shafts of sunlight struck the trees, the bark glowed gold with incandescent fire.

Presently I remembered and, glancing furtively from the corner of my eye, saw Sebat, birch horn in hand, standing just behind, highly amused as usual.

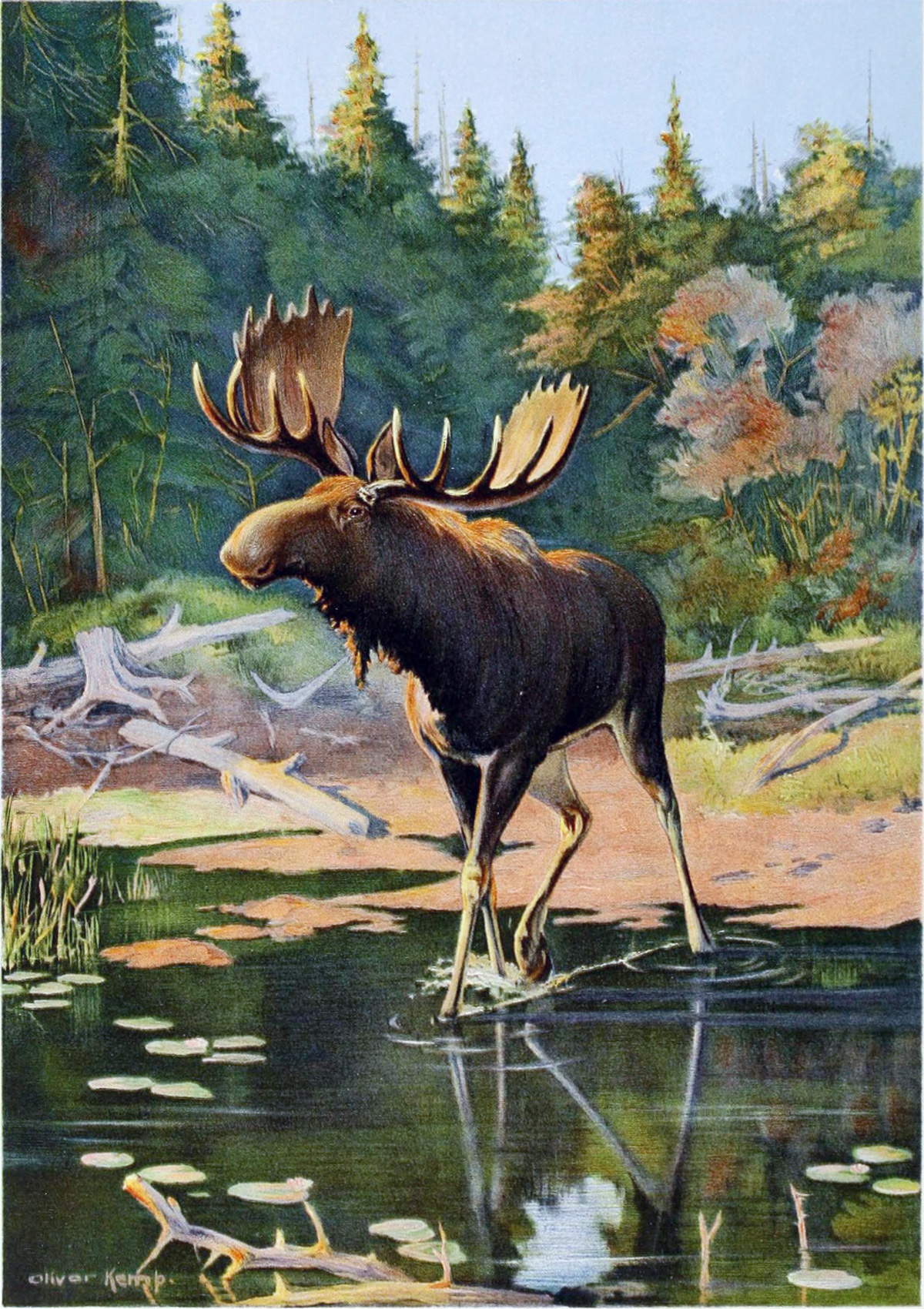

The Moose by Oliver Kemp.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“No good,” was his triumphant reply.

“Damn it all, draw it yourself then,” and I proffered the materials.

To my astonishment, he took them, and, seating himself at the foot of a birch tree, with much deliberation he proceeded to draw. It was a slow process, and presently the landscape was forgotten. All his hopes lay at the point of the pencil. He was plainly anxious to use the paint, and several times he tried it with evidently disappointing results.

Meanwhile, just above us in the bog, a bull moose stepped out and wandered slowly along, disappearing occasionally behind the scattered clumps of trees and bushes. Sebat was all unconscious. At last the picture was finished, and once more the grin appeared as Sebat held it at arm’s length.

“Well, what do you call it?” I asked.

He viewed the drawing from various angles and answered slowly: “I call um damn fonny.”

Then he caught sight of the moose. Instantly he was all hunter, but at a sad disadvantage. There was but one thing to do, and he froze, rigid as a rock.

“Sh-h-h! Moose!” he whispered.

“Sure thing,” I answered loudly; “he’s been there half an hour.”

Sebat shot a look from the corner of his eye, saw me grinning largely, and realized his position keenly, fairly caught with no rifle near and out in plain sight where the slightest movement was fatal to success. He was crestfallen.

“You’re a bum hunter, Sebat.”

“Shoot!” he hissed.

“Not much. We’re here to call, and that chap came uninvited.”

It seemed that Sebat and I were quits.

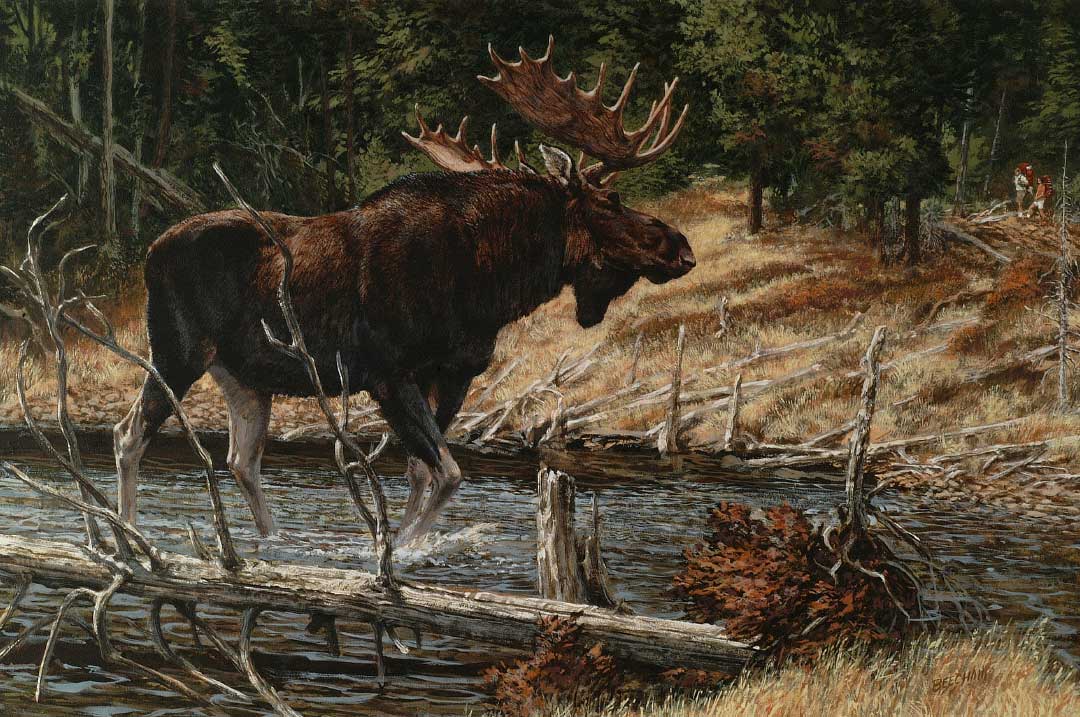

Sometime after, the face of Sebat looked out at me apologetically from a log cabin in Madison Square Garden, and just to clinch my position, I piloted him around to the editorial office where the resulting picture of The Moose Call hung. He did not grin, but when the editor asked how he liked it, Sebat, laying his hand on my shoulder, said: “He’s a good hunter.”