Rarely is the sportsman so situated that he absolutely depends upon game for food, though as one penetrates farther into the North, the sight of hungry Indians is not uncommon; this, too, when the game is generally at hand.

It was after a severe storm that we came upon a village of Indians who were hunting for meat. The sky above had been ominous from the start—a great arch of deepening gray that reached down to the domes of the tents. We turned our faces to the north, only the creaking of the netted snowshoes making a sound. Out of sight of camp, the silence of the great waste gripped us.

Presently, across the soft mounds of snow, there stretched away the slotted trail of caribou. Pete, my Indian guide, and I were following the animals when the snow suddenly came swirling down, the north wind roared and flew whooping across the barrens, and the world turned white in an instant. With backs bent to the frowning forces that came careering after us, we raced along. Only dimly could I make out the Indian’s form ahead, running on his snowshoes—then a misstep and one of the snowshoes broke.

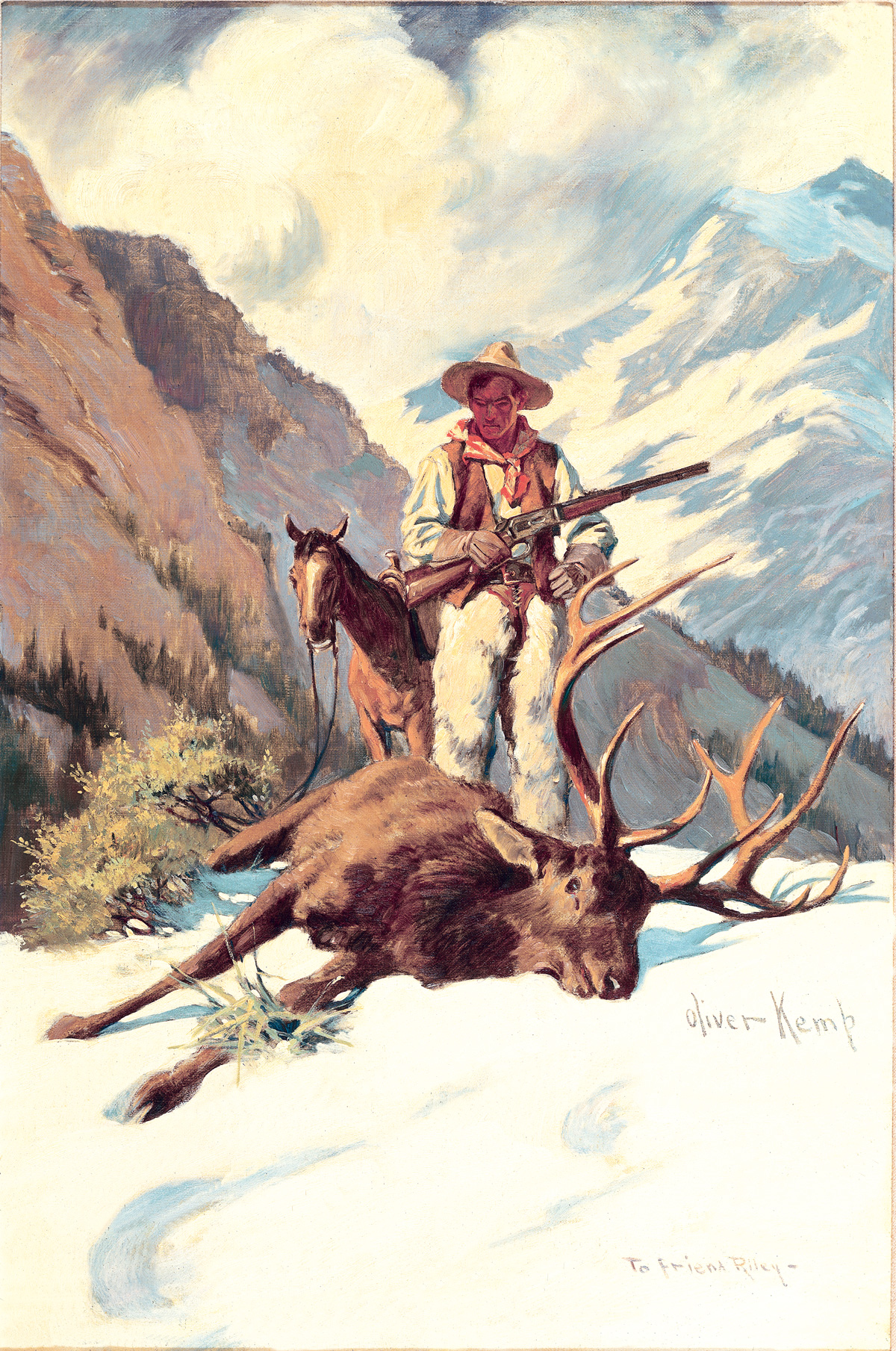

High Country Hunter by Oliver Kemp.

Pete looked at the thing ruefully, and then we made camp. With snowshoes we piled the snow high about us. With a pocket ax we cut branches to lie across the top and piled more snow on them. We dug a hole for the fire in front and were soon fairly comfortable, though somewhat cramped.

It grew cold—bitterly cold; around us we heard the crash of overburdened trees and the crack of timber rent by the frost. I repaired Pete’s snowshoes in a manner of which I was quite proud, but with unabated fury the storm raged through the night and day. Then suddenly it ceased, and across the blue silence of the frozen night there rustled the wavering flames of the aurora. By its light we set out and, traveling through the night, came at last to the campsite we sought.

Alternately we slept and feasted until just before dusk, when our dogs gave notice of an approach, and, thrusting the tent flaps aside, we saw an Indian village just arriving. There was a glorious fight with the dogs, much beating with clubs, and in a very short time six lodges were set up, and the snow was dotted with snowshoes and toboggans.

The Indians were nearly starving, so I produced tea and flour and our last quarter of caribou. Each person had a kettle of tea, and with hunting knives and fingers they made short work of the edibles.

Now I had material for my brush, and during the stormy days worked incessantly to the everlasting amusement of my new friends, who were all anxious to pose. When a drawing was completed and passed around, there was great laughter and banter as they recognized the individual, but particularly when they noted some tear in the garment, a wart on the face, or some other odd characteristic of the one painted.

Thus the time passed, in spite of the pangs of hunger, and when the skies cleared the hunters went out. They shot two caribou that were traveling together, and the scene was gory and awful. The snow was tramped and blood-stained for a wide radius—blood even on the trees, and the Indians themselves were a terrible sight. But everyone was happy, and such a feast as ensued was to be remembered. The skins were given to the women to prepare for tanning, then every other vestige of the animals was cooked and eaten.