We put him “near the ashes of his fathers and the temple of his gods” and we did it through the doors of the church he had joined, as a boy of 11, in 1938.

The scripture for the funeral service was read from the pages of the same pocket Bible that was given to him the day he joined that church 63 years ago, and in common with many small towns and churches across Alabama’s black belt, there has been no appreciable change in the appearance of either the church building or the town in the 63 years that have passed since he first became a member.

He sleeps in the graveyard of the First Presbyterian Church of Camden, some four miles north of the location of the last turkey he shot, there on that height of land that overlooks Gravel Creek. The cemetery itself is just two miles below the bottom curve of Gees Bend, on the Alabama River.

This spring, on cool mornings before the leaves get too big, if you will station yourself at the lych-gate of the cemetery, it will be possible to hear faint gobbles along the south bank of the river. All of which only means that, in addition to being buried with his fathers, he is also buried in the midst of his avocation.

It was not an unusual way for me to spend an afternoon. If a person stays in the same battalion-sized organization for 40 years and holds a position far enough up the rank structure to have had a hand in recruiting, training and working with almost all of its people, he will end up spending a lot of afternoons on handles – those handles that run along the sides of the coffins that are the final containers of friends.

After the church service that afternoon, we had a bitch of a time with the box. None of the pallbearers could be described as being in the first flush of young manhood. A couple of us have grown rather long in the tooth, and while the load itself was not in the least heavy, the path was rough. The hundred yards from the back of the hearse to the gravesite itself passed over exceptionally narrow and crooked cemetery walkways – walkways bordered by raised, concrete copings that have fallen into a poor state of repair.

In my own particular case there was an additional load. I carried, besides my share of the coffin, the weight of 42 years of memories piled on top of the box.

A 42-year collection of memories, even those of the lightest and most joyful occasions, weigh somewhere in the neighborhood of a ton-and-a-half.

We not only worked together, the man in the box and me; we hunted together, which tends to let you look at a man’s qualities from a wide variety of perspectives. If there was ever a cross word between us, or a cross purpose, for so long a period as a minute-and-a-half in all of those 42 years, I cannot recall it, and I am unable to make that statement about any other human being, living or dead.

My friend, Jim Hart Andrews, had built his reputation principally upon public turkeys, rather than private, his uncanny ability to handle what are known as “give-aways” bordered on the supernatural.

It is impossible to overstate the difference between public and private turkeys.

Private turkeys are more or less like the members of cloistered religious orders. Kept behind locked gates, protected from prying eyes and hands, guarded, controlled and cosseted. Private turkeys are hunted only by whatever selected, chosen individuals the owner of such turkeys happens to find worthy. Such turkeys are frequently further protected by a series of rules and restrictions substantially beyond those considered legal and necessary by the various state authorities.

No yearling gobblers are shot, for instance. A minimum of a thousand acres per hunter is laid off so that no hunter need feel crowded for space and can go to any turkey he hears. Various parts of the territory are not hunted at all and there are periodic rest days staggered throughout the week for those areas that are hunted. Vehicle movements are restricted into and across some areas and no vehicular traffic is allowed at all during certain times of the day. All of these actions are designed to create, as far as possible, a degree of serenity, an impression of solitude, and a relatively calm, relaxed and untroubled turkey to hunt.

You cannot return to the days of Boone and Crockett, but given enough money and sufficient land, a close approximation becomes possible.

Mind you, I find none of this offensive. I have great good luck to be invited to hunt on such areas and under such conditions from time to time, and it is like getting money from home without asking for it.

Public turkeys on the other hand are about as far as being calm, relaxed and untroubled as anything you can imagine. They may be listed as members of the same species by taxonomists, but in their approach to their surroundings they have crossed the species divide and accepted membership in another genus. On the upper, ragged edge of that classification, as a matter of fact, very near the point where genus crosses over into family.

Public turkeys are street-smart. Public turkeys know all the answers and a great many of the questions. Public turkeys have been hounded for decades by successive generations of lean, close-lipped, suspicious rednecks wearing faded overalls and black hats who had, and retain, very little sympathy with bag limits, game laws or legislated, pettifogging regulations.

Public turkeys take no prisoners.

Until near the end of his life, Jim Hart Andrews was a man of relatively modest means, unable to use rank or position to afford much access to those cloistered and protected turkeys that live like rich sardines in their private cans. He was forced to duke it out with shifty-eyed turkeys on the brink of paranoia, turkeys being chased by every redneck in the county, turkeys born and living under Damoclean swords, suspended by inferior hairs.

You make it with these and you can make it anywhere.

Jim’s second area of qualification was his performance with giveaways.

Giveaways are a breed apart, and his handling of them had to be seen to be believed.

There is a distinct difference between a giveaway and a presentation. Presentations are those turkeys called up for another person, while you and that person are in one another’s company and the person who calls the turkey up, presents it to the person who has the gun.

Giveaways are those turkeys given by location. They are usually given in surrender, because they have been worked three or four times, the person who found the turkey cannot handle the situation, and he gives it to a friend with an invitation to try. It is not at all the same thing as knowing where a turkey has been gobbling, knowing he will continue to be in the same general location, and passing this information along to a friend or guest in an attempt to improve his chances. A giveaway is the definition of one you have been fooling with, have given up on, and the tone of the transaction is usually one of, “I have been fooling with the son-of-a-bitch since last Thursday and he whips my ass every morning. Go see what you can do with him.”

Some of these have been given away, then given back, and then given away again. They usually are very old, very wise turkeys and by the time proprietorship has been transferred two or three times, become call shy, noise shy and suspicious of everything and every sound – even imaginary sounds.

They are so difficult they are sometimes given in hate. A man will give one to an individual he secretly dislikes, in the hope of making the enemy look ridiculous.

My friend had a success ratio with these things that was better than the combined success rate of any other three men I ever knew.

There was a remark made, by one of Jim’s competitors, about Brooks Robinson’s play at third base when Brooks was performing those daily feats of prestidigitation for the Orioles. He said that Brooks just played in a higher league. The remark fits here.

When it came to turkeys, Jim Hart Andrews, all his life, simply played in a higher league, and there have been some unexplained oddities about his career, even after it closed, which deserve some discussion.

Doctor Albert Moore, head of the History Department and Dean of the Graduate School of the University of Alabama, wrote a History of Alabama that was published in the early ’30s. In the chapter of the book that covered Alabama during colonial times, he refers to a custom prevalent at that time not only here, but all over the South.

An individual who died was generally buried very quickly, a normal procedure in warm climates. After his death, especially if he was a man of some prominence in a community, there would be another service held some weeks after the burial. During the intervening time it was expected that the preacher would visit and consult with people who had known the deceased, people who had business dealings with him, people who had been in a position to form a judgment on his character. In the case of an individual who had been known to the preacher, it was expected that he include in his analysis personal observations he had made.

The second service was called the funeral oration and at this one, the preacher informed the congregation as to which direction, in his opinion, the soul of the deceased had gone.

It is the rationale behind the statement, still heard in the rural South, that such and such a man has been preached either into Heaven or into Hell.

Doctor Moore comments at length about the popularity of these funeral orations, the distances people would travel to hear one, and the degree of hard feelings engendered in relatives of the dead man if the oration suggested that the probable movement of the soul had been in a downward direction.

We don’t do this anymore, even in Alabama. Our society, which never assigns blame to anyone, never takes personal responsibility for any action, holds as an article of faith that anything that happens was the fault of person or persons unknown, and regardless, wouldn’t put up with this degree of hardassing, even for a minute. Our over-permissive and totally blame-shifting society would never allow such an oration, and I would have been willing to bet that there had not been one delivered in this state, even in one of the backwoods, serpent handling congregations, since 1910.

But I am pretty well convinced that last Easter Saturday morning in Pickens County, Alabama, I heard one.

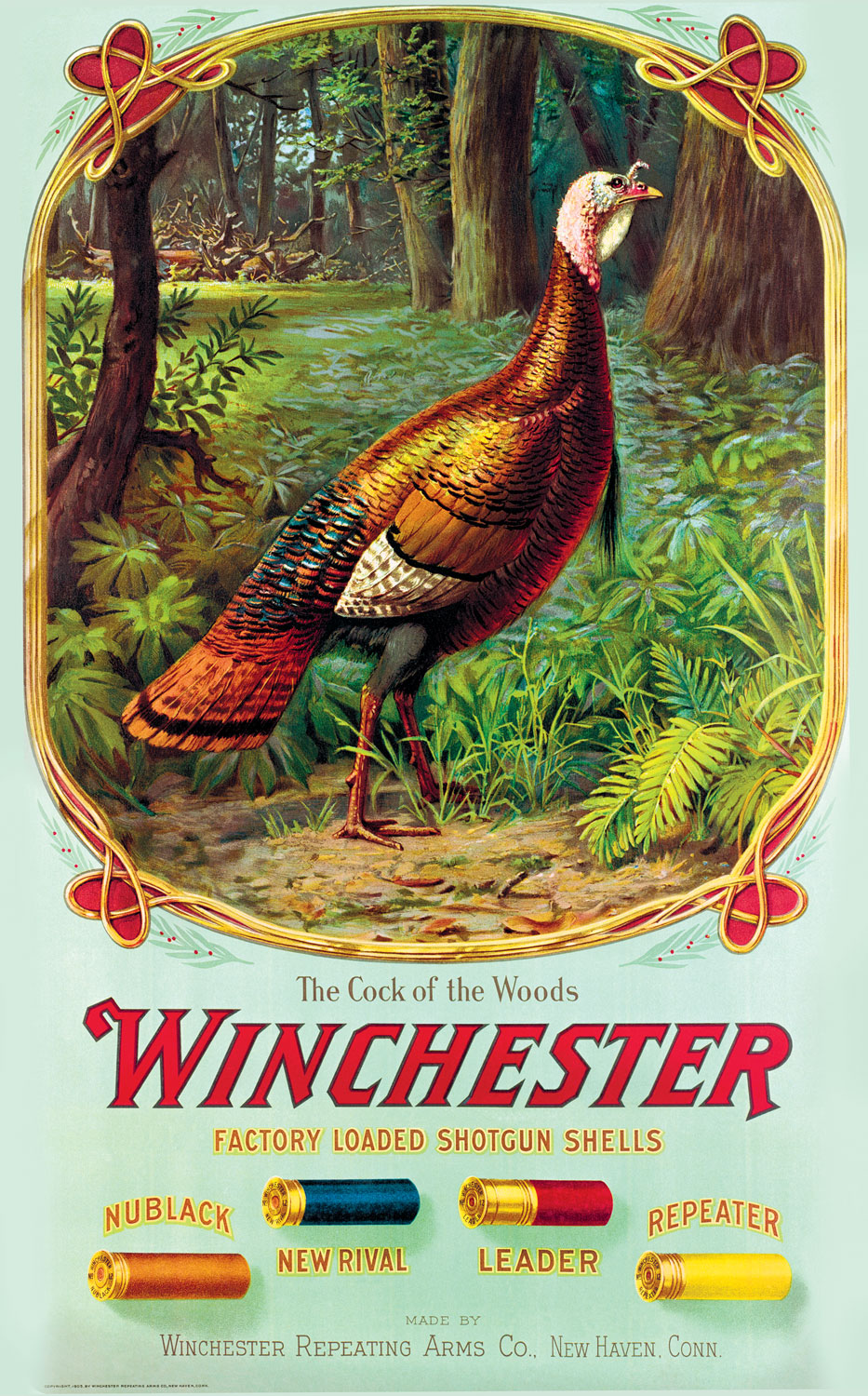

Wild Turkey by Bob Kuhn – Courtesy The Remington Collection.

The client I had taken to the woods Friday morning had to leave before the hunt was over. The next morning, Saturday, I was left to hunt alone. I went to the south side of the pond we had been near the previous morning, stood where I could tell which side of it a turkey was on, assuming one gobbled, and waited for daylight.

West of where I waited was another pond about 150 yards wide, with standing water about 18 inches deep in the middle of it and west of that, and across a green field, was still another pond.

In dry weather, cottonmouth moccasins frequent whatever water there is, and while it was light enough to see individual trees on the way across the pond, you could see nothing at all under your feet. The water was not continuous; there were downed logs and occasional spots of bare ground, which turned the whole place into perfectly splendid moccasin habitat.

But there was, like always, a partial solution.

In the entire genre of outdoor writing, I have never seen a reference to cottonmouth moccasins attacking moose. So, clearly, the proper course was to go to the turkey gobbling across the first pond by walking as much like a moose as possible in order to delude those moccasins that might be present into thinking that the approaching animal was not suitable prey.

I have not seen all that many moose. I worked at one time for a company that owned considerable land in Maine and Nova Scotia and, during sporadic visits, had seen enough moose to be struck by their walk.

A moose appears to move almost like a Tennessee Walking horse. There seems to be no up and down movement to his back as he progresses. If you cannot see his feet, it appears as if he was mounted on wheels, and some force was pulling him along at the end of a rope, and he steps out briskly.

So I crossed the pond at a walk almost fast enough to be called a trot, and made no attempt to lift either foot out of the water as I moved along in order to make as much noise and be as moose-like as possible.

By the time I got out of the pond, leaving whatever moccasins there may have been in there completely befuddled by my crossing tactics, there was a second turkey gobbling. This second one was very near the first, and by the time I had crossed along the south edge of the green field and gotten into the woods on the other side, there were at least two additional turkeys gobbling in the same location.

There was a first-class natural blind in a clump of buckeye bushes at the base of a two-foot ash, and all I had to do was sit down and get comfortable.

There were positively four turkeys, I am morally certain there were five, and they gobbled at every sound but one.

I have a distinct reluctance to yelp at turkeys on the roost more than once or twice. They are up there gobbling to attract hens. If you yelp and they hear it, they assume you are a hen and expect to see you arrive momentarily. You keep yelping, they never see an approaching hen, and suspicion rears its ugly head. In this particular situation the point became moot because all of these turkeys flew down in the first five minutes I sat there, and the gobbling on the ground was unlike anything I have ever heard.

They gobbled at crows, at owls, at a pair of red-shouldered hawks screaming just behind me. They gobbled at each other, they gobbled at wood ducks squealing in the pond behind them, they gobbled at every single sound, but me, and they did it for thirty minutes by the clock.

You will hear two-year-olds, still in their early season flocks, do this occasionally. One gobble will trigger two or three more, yelling begets yelling, as it were, and with no dominant gobbler around to enforce order and decorum, they can be unusually noisy. But not old turkeys, and it was too late in the season for entire flocks of two-year-olds to be having this free a hand and, obviously, all of them could not be dominant.

I never got an answer. I never made any turkey stop gobbling. I was treated, from beginning to end, completely as a non-person. No sound I made, or didn’t make, had any effect upon the proceedings whatsoever, until they all finally shut up and walked off.

In 62 years, I have never had a similar experience.

The thought occurred to me on the way back home that it was as if I had been attending a performance.

And then I was struck with the thought that maybe I had been.

Maybe it was a funeral oration, handled from the other side.

The time span since the burial was within the proper frame. Nobody says the oration has to be delivered in the English language. Nobody says the orator has to be wearing black broadcloth, rather than feathers. Nobody says attendance at the service cannot be sparse, maybe even singular.

Maybe when these things are handled from the far side, rather than the near, they do them in different ways and this was simply a collection of Jim’s new friends sent down here to tell the world they had welcomed him through the gates.

As far as I was concerned, the entire oration, if it was one, was conducted simply as a matter of confirmation and could serve to convince those persons still in doubt. There was no need for it at all, if it was being done for my benefit.

I already knew which way he went.

To order Tom Kelly’s books, call Sporting Classics at (800) 849-1004 or click here to buy online.