British gunmakers have long had an enviable reputation for turning out superior sporting guns and rifles. This has been mainly because from the very start they have always catered to the well-to-do class of discriminating sportsmen who have demanded the very best and, who by training and antecedent, expect superior ballistic performance, durability, fit, beauty and individuality in their weapons. The older British sportsman takes pride in turning his old and well-used guns over to his grandson in his declining years.

Our American arms factories have never been prepared to meet this demand, and indeed until lately there was a relatively small demand of this kind in America. Rather have our manufacturers organized on the basis of modern quantity production, looking for large sales and a small profit on each gun. They have catered almost entirely to the men of limited means and modest desires, their market has been mainly through the sporting goods and hardware stores.

They have turned out good low-priced weapons, but every one more or less alike, methods of manufacture being used which are conducive to economy of manufacture rather than elegance of outline and balance. Made by quantity production, perhaps 25,000 at a time, a certain tolerance in parts has been necessary to ensure strict and economic interchangeability, and certain modification of design has been necessary to keep down cost. All of these militate against the highest efficiency and the fit, balance and beauty which should pertain in really first-rate weapons.

Recent years have shown an astonishing development in rifles and cartridges, and no less of an advance in the knowledge of how to manufacture arms. Our large arms factories have been unable to keep pace with this development. The demand has not been sufficient to permit the entire revolution of the industry in design and methods of manufacture which has been indicated. The changes in American sporting arms during the past ten years have been small and of relatively little importance or effect.

As a consequence, we have seen more and more of our well-informed sportsmen going to British gunmakers to obtain a class of weapons which could not be obtained over here. Five years ago, there were practically no private gunmakers in the United States, the general trade going to our large factories and the higher class trade to England. But as the developments and improvements came, and we became acquainted with these, and learned more of the design, ballistics and methods of manufacture of rifles, we realized that the British gunmakers were by no means keeping abreast of the art. They were entirely too conservative, and they apparently knew nothing of the work of the leading American ballistic engineers. Their weapons were magnificent pieces of workmanship, but they were not up to date otherwise. Thus, there was gradually created a decided American demand for superior weapons which would conform to American development and ideas.

The great improvement in rifle marksmanship in the United States also created a demand for weapons of very superior accuracy, and we found that in the making of really accurate weapons the British gunmakers were hopelessly behind. We had been using very superior sights and a firing position which, with the aid of a special type of gunsling, permitted us to aim and hold for astonishingly small groups. English sportsmen still stuck to older positions and to plain, open, non-adjustable “V” sights, which did not permit of that accuracy of aim which would bring out the capabilities of a really well shooting rifle. British gunmakers apparently knew nothing about all this and could not be educated beyond the standards and methods developed many years ago.

In the making of smokeless powder rifles, they were and still are using standards and methods which were evolved when the .303 Lee-Enfield rifle was first produced about 1890.

As a result of this demand for superior weapons in America, there sprang up lately a number of small, private gunsmiths who cater to the ideas of our modern sportsman as well as their limited skill, equipment and capital will permit. Generally, however, theirs is merely an attempt to convert, remodel and improve existing arms, and to eradicate from them some of their more glaring faults. Military weapons have improved much more than sporting rifles, and much of this work of our private gunsmiths has taken the direction of converting military rifles into sporting types, with superior and individually fitted stocks and sights.

We knew that a well-fitting stock was of even more importance to the rifleman than to the bird shooter, assuring the getting in of a well-aimed shot quickly, and a steadier aim and hold, of primary importance to the rifleman because his weapon may be used against dangerous game. It is true that our large arms factories would make us a stock of special dimensions to order for an advanced price, but always on a certain design which they and not the customer determined.

We knew that slots cut in the barrel for the cheap attachment of sights, forearm tips and mainsprings were inimical to the finest accuracy. Some of these slots we could eliminate, and some not. We knew that a certain fit between bullet and bore, and certain modern principles in the chambering of rifles, were necessary for the highest degree of accuracy, reliability and barrel life, but we could not get these at all. We knew that a certain weight, dimension and shape of barrel was necessary for the highest ballistic efficiency, but these things were so standardized in our rifles and in the machinery for their production that no change or selection was possible.

Practically no attention could be paid to balance, a very important matter when it comes to quick and accurate shooting. We had a few sights from which a selection might be made, but if we wanted something entirely different there was no one who could or would make it. Many of these matters pertain just as forcibly to British gunmakers as to American.

Several years ago, this demand reached a stage where it was so in evidence as to compel the organization of two companies specially to cater to it, to build made-to-order rifles of the very highest grade of material and workmanship obtainable anywhere, of strictly modern design, each one built to individual requirements, a custom-built arm fitted to the individual and his requirements and conditions.

As might be expected, there has been found, generally speaking, to be one best type in design. Thus, among the really expert rifle-bearing sportsmen, these demands and ideas have gradually moulded themselves in certain very definite directions, always in conformity with the findings of our most skilled and up-to-date ballistic engineers. Certain types, designs and methods have been found to be superior to others, and so there has resulted a crystallization into a type of rifle very distinctly American, and very superior to anything ever produced before anywhere, a superiority which extends not only to ballistic efficiency but to sporting efficiency as well. For want of a better name we have come to call this type the “Modern American Rifle.”

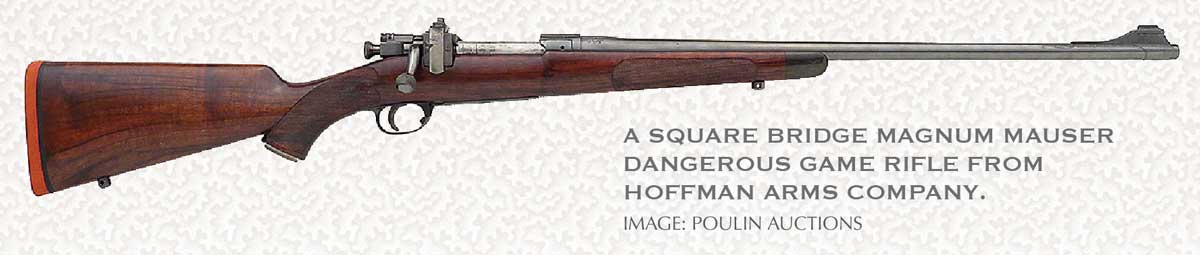

I have before me two of these Modern American Rifles, one made by the Hoffman Arms Company and the other by Griffin & Howe, with which I have just completed a very thorough range test and examination. Let us look over these beautiful weapons from muzzle to butt and see wherein they excel what we have been used to in previous domestic and foreign manufacture, and why they are superior.

Starting at the muzzle, the first thing which attracts our attention is the front sight and base. The front sight blade carries a gold bead with perpendicular surface toward the eye so that it reflects light with even illumination over the whole surface. Behind this bead is a very large white enamel bead turned down in the base, which can be raised for night shooting. The base is secured to the barrel by an encircling band—no slots—and this band at its rear has a long, matted, inclined ramp, which, in the act of aiming, has the same effect as a matted rib on a shotgun, leading the eye quickly toward the front sight.

Then there is a globe, hooded front sight protector which can be slipped on over the base to protect the sight in rough going, or when in a saddle holster, or used as a shade in target shooting.

The barrel is round, without any slots or screw holes whatever, and is made of a high grade of nickel steel which is quite rust resisting. It has about three times the resistance to rust that the ordinary barrel steel has, and also an extremely high elastic limit and resistance to erosion. The barrel is rather thick in diameter at the breech and for about an inch in front of the breech covering the area of the chamber, thus properly supporting the high breech pressure. Then it tapers with the short cone which experience has shown to give the most even and compensating vibration. The remainder of the barrel has a gradual taper to the muzzle.

Looking at the bore we find, first a chamber which is most accurately and smoothly reamed to take the cartridge. This chamber is not cut with the large allowances for speedy production or to relieve possible high breech pressure. Such a tight and perfect chamber is only possible where the makers of the rifle exercise some control over the manufacture of the cartridge that is to be used, which has been assured in this case.

This particular rifle is designed for a certain make of cartridge and not designed to use a number of cartridges made with the variations determined by six or seven ammunition companies. The bullet seat at the front of the chamber is very carefully reamed to fit the ogive, or profile, of the bullet exactly (that is, the portion of the bullet extending outside the case into which the rifling will cut), the tolerance being less than .0002 inch.

The arrangement of cartridge, chamber and bullet seat is such that when the cartridge is placed in the chamber, the bullet seat takes ahold of the bullet and straightens it up so that its axis is in exact line with the axis of the bore, and thus, when fired, the bullet moves straight forward in perfect alignment with the bore and receives practically no deformation in so doing.

With all our older rifles, and with most foreign rifles, the chamber is quite large to allow for a number of contingencies which seldom occur. The cartridge lies at the bottom of this large chamber and the bullet, before discharge, is cocked up at more or less of an angle with the axis of the bore. As a result, the bullet is more or less deformed upon entering the bore, which precludes the finest accuracy, and the bore itself is gradually eroded at the bullet seat.

Now we come to the breech action, which in this case is of the Mauser type. There is no better action than the Mauser when properly made. It is the most fool-proof and the most reliable. Its primary and secondary cams give it more power to insert, extract and eject a dirty, sticky or oversized cartridge than any other breech action. A pressure or pull of 25 pounds on the bolt handle results in a translation of 175 pounds on the head of the cartridge. This is of exceeding importance, for a rifle to be used in emergencies where the life of the sportsman is sometimes at stake should never fail to eject the fired case and insert the new cartridge. The breech bolt is supported by locking lugs at its head.

In many domestic rifle actions, the lug or bolt is at the rear of a long breech block, and this is now known to be detrimental to accuracy and durability, as well as being a bad engineering principle.

The steel of the breech action has an exceedingly high tensile strength and is heat treated in addition to give it an exceedingly hard surface but a tough interior. No amount of shooting will cause any upsettage, and the mechanism will wear out many barrels.

As contrasted to this, many of our less modern breech mechanisms, and a few of the foreign ones, are made of a soft, easily machined steel to enable manufacture to be speeded up and cost decreased. These steels are not heat treated. Most of them, however, have a good elastic limit. Breech actions of this kind of steel are perfectly safe, yet they do not wear like the special heat-treated steel. A common defect is to have the breech bolt acquire a permanent set back after several thousand rounds have been fired, increasing the headspace, so that very often a cartridge, on being fired, will have its case stretched to an undue extent, and the case separates—splits in two circularly about half an inch in front of the head. When this occurs the breech action is worn out.

All of the working parts of this Mauser breech action are most beautifully machined, and in addition have been most carefully polished and adjusted with the finest valve grinding compound so as to give the most perfect fit and smoothness of operation. The trigger pull has been hand adjusted to give a pull of 3 1/2 pounds which has not the slightest suspicion of creep or drag. The trigger, safety and bolt handle are all checked to prevent any possible slip of fingers in operating or firing. The upper surface of the receiver has been matted to prevent any possible reflection of light interfering with a perfect vision of the sights when aiming.

Progressing again toward the butt of this rifle, we find a new model of Lyman type of aperture rear sight. This aperture is close to the eye, just far enough away so that the eye stands in no danger of being injured when the rifle recoils. The result is that in aiming, the aperture is seen as a quite large but thin circle which does not interfere with the view of the target or surroundings, thus making aim at running game a very easy matter. Moreover, one quickly comes to seemingly disregard this rear sight in aiming, and to apparently align the front sight only on the game, with enormous resulting simplicity and quickness of aim.

As a matter of fact, however, one cannot fail but align the rear aperture accurately with the front sight and the game, although not conscious of doing it, and thus extreme accuracy results owing to the very long sight radius. Looking still at this sight, we see that this aperture is readily and positively adjustable for both elevation and windage, and that the adjustments read to minutes of angle, roughly a change in point of impact of 1 inch at 100 yards, 2 inches at 200 yards, and so on.

Of course, very few well informed sportsmen or practical shots attempt to change their elevation or windage when shooting at game. They have their sights accurately adjusted for some particular range, and for other distances hold over or under the game. But the point is that without a most accurately adjustable and recordable rear sight, it is almost impossible to ever get a rifle sighted for any distance with exactness, and the ammunition bill chargeable to sight adjustment and targeting is usually large enough with crude sights to pay for the improved sight many times over. Moreover, without properly adjustable aperture sights, sportsmen practically never develop real nail-driving marksmanship.

Perhaps the thing which would first impress the novice when he took up one of these fine rifles would be the stock of beautifully figured Circassian walnut. Not only is the wood decidedly superior in figure, beauty of lines and strength, but it is shaped and designed to be a perfect fit for the man for whom it is made, so that when this man throws the rifle to his shoulder, he will invariably find the sights aligned with almost perfect accuracy upon the object at which he is looking.

Forearm and pistol grip are sharply checked. The forearm is large enough to give a firm grip for the hand, so that the bottom of the forearm is down in the palm of the hand supported by the bones of the forearm, not perched up on the fingers, with every bone and joint of each finger contributing to the tremor. The pistol grip is a real grip, not merely an excrescence on the underside of the stock, but pushed up near to the trigger guard so that when the hand grasps it, a real backward pull can be obtained without effort, and yet the trigger finger need not contribute to the grip, but stands limber and relaxed for its delicate work of trigger squeeze.

The comb of the stock is quite high and thick so that the side of the face finds full and perfect support against it, and the eye is held steady in the line of aim while sighting. The butt-plate is of steel, sharply checked so that it will not slip on the shoulder, and also so that it may occasionally, if need be, be used as an aid to climbing rough and steep mountains without chipping. This butt-plate is full man-sized, 5 1/8 inches long by 1 5/8 inches wide, the size and shape seen on the finest shotguns. It has an opening and trap door, and imbedded in the walnut stock under it are a jointed cleaning rod, brass cleaning brush, small one-drop oil can and a supply of cut flannel cleaning patches, all ready for emergency cleaning if one should be forced to stay overnight away from his camp supplies.

There is a leather gunsling, too, not the usual strap, but a real shooting gunsling with adjustable loop so that it can be used in that most accurate of all shooting positions, the standard military prone position. The sling swivels are strong and noiseless, and do not twist or tangle.

When I came to fire one of these rifles, I obtained one group in which all the shots could be enclosed in a 2.2-inch group at 100 yards, and another with ten shots inside a 1.7-inch circle at the same distance. The average thus was slightly less than 2 inches. Two inches at 100 yards is equivalent to 6 inches at 300 yards, and the average machine-made quantity production rifle using cartridges designed 20 or 30 years ago, makes about a 4-inch group at 100 yards, or 12 inches at 300 yards.

The various vital spots on a big game animal, to hit which usually assures one’s getting his game without needless suffering, are generally taken to be about 6 inches in diameter. Therefore, with these Modern American Rifles, one can come pretty near commanding his game up to 300 yards if he be a good shot, whereas with the older rifle the distance will not be much over 150 yards at which he can make absolutely sure.

We have, therefore, in these rifles weapons which are more accurate, reliable, durable and beautiful than rifles were formerly made, with which the sportsman can make sure hits more readily and farther away and faster, which, by reason of their superior ammunition, give vastly increased killing power. This is the Modern American Rifle; the weapon for sportsmen who can afford it and who wish to take every precaution to assure the success of their shooting trips; or for the intrepid explorer who separates himself for months and by hundreds of miles from any possible source of supply or repair. Such types of superior weapons have ushered in a new era in the art of gunmaking.

This article originally appeared in the August 1925 issue of Forest and Stream magazine.