All writers are liars, whether reef-fishing miles offshore on the Atlantic or fishing through a hole in the north country ice.

The smokestack of the hulk gloomed from the depths, barely visible when the July sun ricocheted off the surface of the sea. Halfway to the Gulf Stream in 90 feet of water, she “was the Betsy Ross, a Liberty Ship from WWII. We turned them out faster than the Japs or the Nazis could sink them, and they won the war, but they would not last forever. Dynamited and sent to the bottom, Betsy Ross was joined by the majority of a concrete bridge, sundry surplus amphibious assault vehicles, New York City subway cars, and lastly by the barge that hauled them all out there. Barnacles and seaweed brought baitfish, baitfish brought bigger fish and bigger fish brought cobia, mackerel, snapper and grouper. You never quite knew what you would catch at the Betsy Ross.

But that day the fishing was real slow. We had live blue-runners and porgies at various depths, the rods on free spool, and the bait found action in the gentle roll of the boat, sideways to the wind and sea, a 30-footer with twin 250s. The captain had the VHF on 16, in case anybody was picking up fish on the Snapper Banks, a live coral bottom another 20 miles to sea.

I fetched up a brew and chanced to break the no fish miasma. “Did I ever tell you boys about ice fishing in Minnesota?”

There were pained expressions from all hands, but if a writer is going to be deterred by pained expressions, he would never utter a single damn word.

“No,” the captain said, “but I got a feeling you’re fixing to.”

The mate rolled his eyes, fetched up a plug of Beech Nut and bit off a corner. He only chewed when fishing or hunting wild hogs.

“We’d drive about fifteen miles on the ice to get to our fishing spot, at night sometimes.”

“Well, why in hell would you do such a thing?”

“Same reason we’re to sea in a thirty-foot boat.”

The mate jawed his Beech Nut, just starting to make juice, spit over the side.

“So it’s froze up half the year and you gotta keep fishing?”

“You got it. They got pressure ridges like in National Geographic, ice busted up and hove six feet. Pickaxe it down, lay planks. You drive up close, set the planks to match your wheels, open all the doors and rattle across.”

“How cold you talking about?”

“Twenty, thirty below.”

“How come you open the doors?”

“Cause if you break through, the truck will hang up, not sink.”

The captain shook his head, the mate mumbled a cuss. One of the reels clicked a time or two, nothing more. A gull came sliding along the breeze, fixed us with a skeptical eye, flew on.

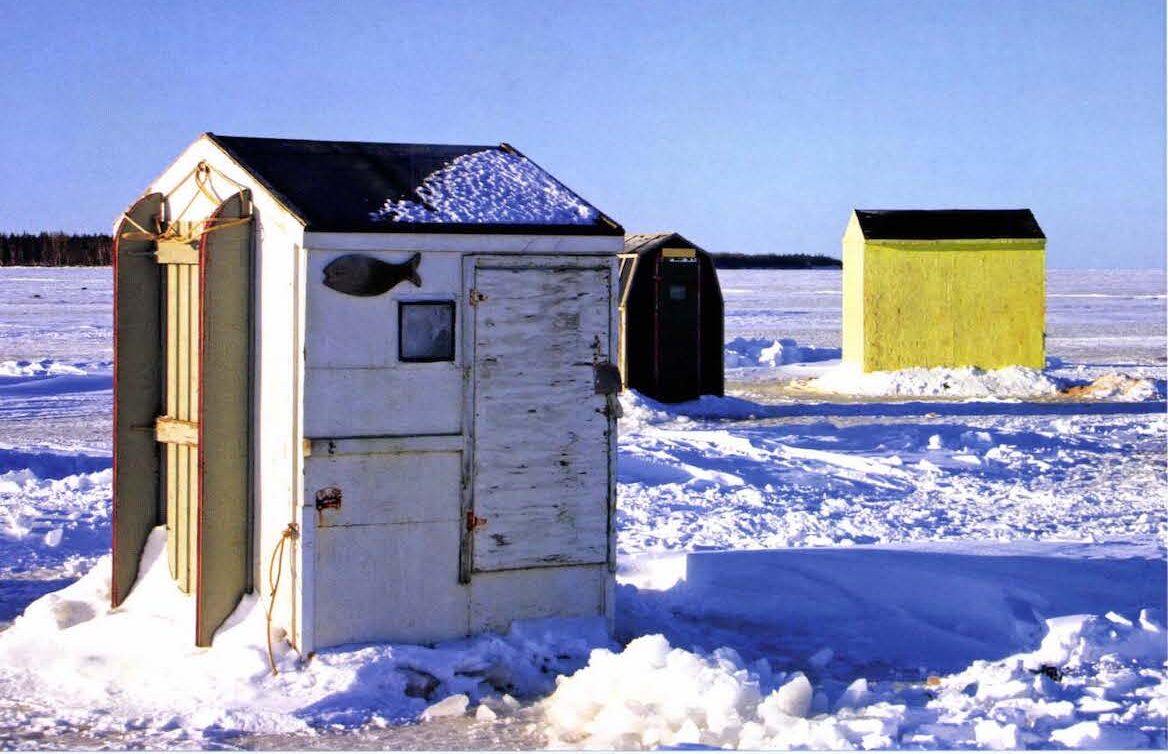

“But that’s way up north. Close to Minneapolis, they got whole towns out on the ice – I mean two thousand people, two-story fish houses. They got streets and street signs and satellite TV and pink flamingoes. They got carpet and holes cut in the floor and rattle reels to wake you up in the wee hours.”

The captain shook his head, “You’re stretching it now,” he said. “And they actually catch fish?” the mate asked.

“Man, they build fences of fish, walleyes and pike froze tight and stuck nose-down in the snowdrifts. They got pizza on call. They even got women carrying stale donuts door to door … ‘You want something sweet, Snookums?'”

“What in hell is a Snookums?”

“That’s what your great aunt calls you when she pinches your cheek. If a young gal pinches your butt, it means you might get some.”

There was a general head-shaking all around. The Captain upped the ante.

“Now you’re fixing to tell me they take a backhoe out on the ice, dig a ditch, and run up and down while they troll for fish?”

“No, but they pull a mile of seine beneath the ice and when they get it all drawed up, they use a backhoe to scoop up the carp and buffalo fish.”

“They really dip fish with a backhoe bucket?”

“No, they got a dip net made of chain link fence. I seen sixty thousand pounds in a single haul.”

“Oh my aching ass! I can’t stand no more of this!” The captain slapped his leg and snorted. “All you writers are liars.”

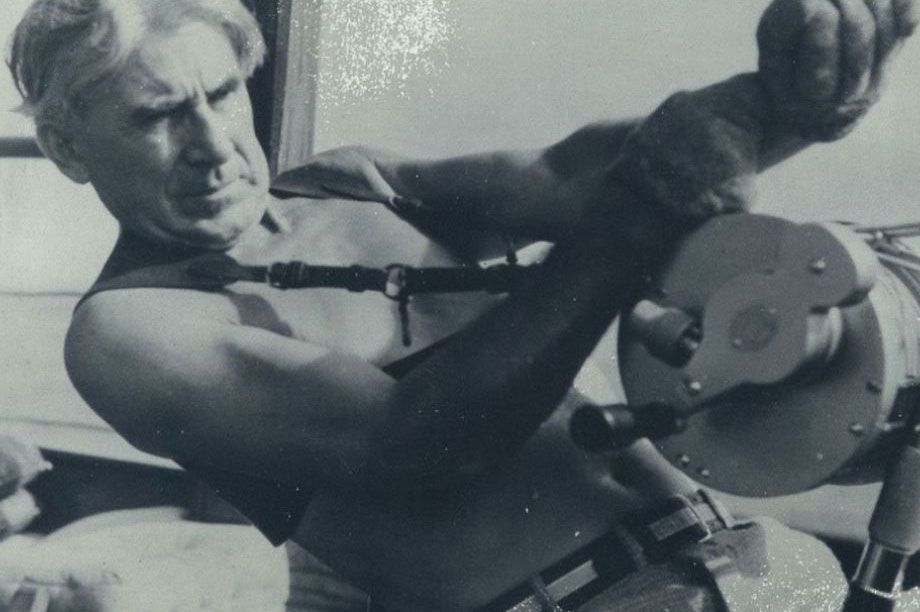

The captain stomped to a forward locker, broke out swim-fins, face mask, weight belt and spear gun. There was a three-knot tide running over the wreck, so the mate tethered him with a length of anchor line to the waist and eased him down atop the Betsy Ross.

Ninety seconds he was back at the boat, hauling a sizable cobia. Cobia look like a cross between a catfish and a shark, and they eat almost as good as mahi.

I got the gaff in him and struggled him aboard, 40 pounds, maybe 50. The captain sunk from sight again and next time came up with an equally large amberjack. I’m suspicious of jackfish. They’re excellent smoked but they can give you reef poison – ciguatera – a nerve agent worse than anything the Iranians got. In mild doses ciguatera makes hot seem cold and cold seem hot. Down in the Bahamas, locals lay the filets out on the dock. If the flies swarm it, it’s okay; if not, it can kill you deader than a mackerel.

Speaking of, the next fish aboard was a Spanish mackerel about as big as they get, 30 inches, a dozen pounds. We got king mackerel and Spanish mackerel down here. Kings grow bigger, and the meat is light and fine, but the Spanish is smaller and generally adjudged greasy and strong. But gut a Spanish, leave the head on, don ‘t skin or scale. Run a green wax myrtle stick through the mouth and out the other end, and broil it over a beach driftwood fire till the grease stops dripping, peel the skin and gnaw it right down to the backbone … oh yes. The coons and ghost crabs will clean up the mess.

I reached down to haul him over the side when a five-and-one-half-foot barracuda lunged from beneath the boat, took ahold of the fish. Long and lean, quicker than a greased diamondback snake, choppers like a buck-toothed muskie, a ‘cuda don ‘t know how to quit.

So we had one helluva scramble, me and the mackerel and the barracuda, slashing teeth and bloody foam just inches from the captain’s nubbins. If not for his canvas britches, the Captain would have likely been singing in the soprano section.

The barracuda won the battle, like they always do, gnawing and thrashing the mackerel off the spear, then swimming away grinning. I held on till there was nothing left to hold onto.

“I’ll tell ’em about all this in Minnesota,” I said, “but they won’t believe it.”

“And why not?” the captain asked.

“Cause all us writers are liars.”

The brilliant fisherman, instructor, and public speaker Lefty Kreh is perhaps the best known, most respected, and most beloved angler in the world today. My Life Was This Big takes readers on an angling journey through the last half century, when water was big and fishermen were bigger. But, despite all that’s changed since the fifties, when Lefty began his career as a professional fly fisherman and writer, fishing is still just fishing.

The brilliant fisherman, instructor, and public speaker Lefty Kreh is perhaps the best known, most respected, and most beloved angler in the world today. My Life Was This Big takes readers on an angling journey through the last half century, when water was big and fishermen were bigger. But, despite all that’s changed since the fifties, when Lefty began his career as a professional fly fisherman and writer, fishing is still just fishing.

In My Life Was This Big, Lefty shares his tales of fishing expeditions with Fidel Castro and Ernest Hemingway, as well as solo battles with some of the scrappiest, most elusive fish in the world. Lefty also takes the reader through the development of his world-famous “Deceiver” fly style, and takes on the issue of conservation through catch-and-release. These timeless, often hilarious stories will put you in the boat with Lefty—and even teach you a thing or two about fly fishing along the way!

This is a glimpse into the heart and soul of Lefty Kreh—a man who has written for nearly every outdoor magazine in the United States; a man who has fished some of the remotest parts of the globe; and a man whose books and articles have taught thousands of people his techniques for hooking and landing more fish. For fans both young and old, these are Lefty’s stories. Buy Now