From the Guns & Hunting 2015 issue of Sporting Classics.

It’s a matter of record that Aldo Leopold — a passionate, lifelong hunter of upland birds and waterfowl — shot a 20-gauge Fox, a gun that, famously, was made-to-order for him without a safety. Having been privileged to know several people who hunted with Leopold — all former students of his at the University of Wisconsin — I’ve been aware of this for close to 30 years.

But despite my admiration for the author of A Sand County Almanac (a man whose work has influenced me profoundly on a number of levels) and my enthusiasm for Fox shotguns (one of which, a 102-year-old 16-gauge CE grade, I’m fortunate to call my own), the idea that I’d one day lay eyes — or hands — on Aldo Leopold’s Fox never entered my mind.

It wasn’t that the gun had been lost the way another Fox, Nash Buckingham’s legendary “Bo Whoop,” had been. Leopold’s gun remained in his family, although pinpointing who had it at any given time was hard to do. I just couldn’t stretch my arthritic old brain far enough to conceive a scenario that would put the Leopold Fox and me in the same place at the same time.

All of which helps explain my appearance of slack-jawed witlessness when Buddy Huffaker, the executive director of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, innocently asked “Would you like to see Leopold’s Fox shotgun?”

Along with our mutual friend Howard Mead, Buddy and I were sitting in the Leopold Legacy Center, the handsome stone-and-timber structure near Baraboo, Wisconsin, that houses the foundation’s offices. The building stands a few clicks up the road from the Shack, the former chicken coop that served as the setting for so many of Leopold’s classic essays on nature and our place in it. Indeed, a tour of the Shack was the reason Howard and I had made the trip.

And now, having only known Buddy a few minutes, I fell into a passable imitation of a mental defective. “Wha-wha-what?” I stammered. “Did you say you have Aldo Leopold’s Fox?”

“I did,” Buddy smiled. “His grandson, Fritz Leopold, called me not long ago and asked if we’d like to have it. I told him we’d be thrilled.”

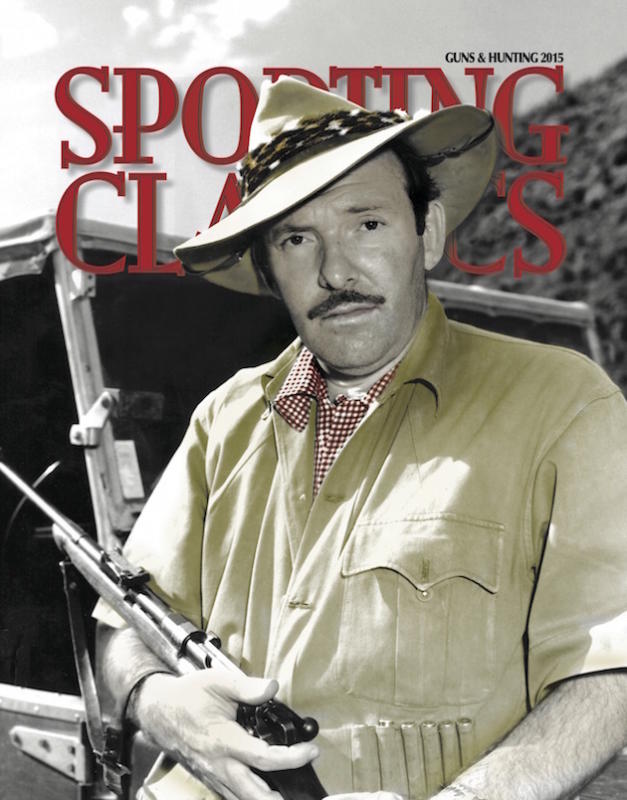

With his Fox double under his arm, Aldo Leopold leaves the warmth of his Missouri cabin for a hunt along the Current River in the Ozark Mountains.

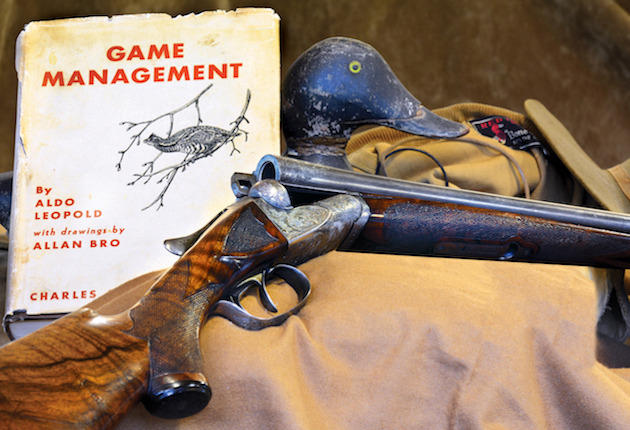

With that, Buddy got up, left the room, and reappeared about a minute later bearing the promised object. The gun was uncased, and the first thing I noticed as I accepted it reverently into my hands was the impression of length it conveyed. I expected a measure of lissome elegance — it virtually goes without saying in a 20-gauge Fox, which its maker touted as “the most perfectly proportioned small-gauge gun ever built” — but this was several degrees above the norm.

I eyeballed the barrels at 30 inches (an estimate that was later confirmed), and as I studied the extensive foliate engraving I realized, with a mixture of surprise and delight, that the gun was an XE grade — the third-highest grade in the Fox line, and, in the words of Fox historian Michael McIntosh, “one of the handsomest of all Fox guns.”

This told me something. Aldo Leopold recognized and appreciated quality, whether it was in land, men, or tools, but he wasn’t routinely given to extravagance. This wasn’t the gun he needed, it was the gun he wanted. It’s a crucial distinction — as all of us who’ve dreamed of owning a truly fine firearm understand.

Leopold’s middle son, Luna, relates a charming anecdote that speaks to this in Robert McCabe’s memoir, Aldo Leopold: The Professor. In 1933, when things were tough all over and especially so for the Leopold family (they were essentially living on Aldo’s savings while he waited for his appointment at the University of Wisconsin to come through), Aldo asked Luna what he planned to do with the money he’d earned that summer — the princely sum of $90.

Luna replied that he thought he’d better use it for his college tuition.

“Well,” Aldo mused, “I think you ought to use it to buy a really good shotgun to replace the old single-barrel you’ve been using…I’ll give you the extra $30 you’ll need to buy a Parker.”

I noted the absent safety — a feature (or non-feature) that was not uncommon among sportsmen of Leopold’s generation. Nash Buckingham, for instance, specified that his Burt Becker-bored Super-Fox — the gun later dubbed “Bo Whoop” — be made without a safety.

The one aspect of Leopold’s gun that I found a little curious was its full-pistol grip. Of the three possibilities, that would have been my last guess. A straight-hand stock would have been my first, but again, it was clearly a matter of personal preference. And the curve of this grip is so gradual and graceful that it could almost be mistaken for a half-pistol. In any event, it’s a far cry from the grotesque hooks that pass for pistol grips on so many contemporary guns.

Leopold on a pheasant hunt with his German shorthair, Gus, near his Wisconsin shack in 1943.

The stock — Circassian walnut, if the catalogue copy is to be believed — displays lovely figure and contrast, and while the points of the checkering are worn, that’s only to be expected. The gun’s in remarkably good condition, all things considered, but it’s obviously a gun that was used and used hard. Leopold himself shot it for 27 years, and his descendants continued to use it for many years after his death in 1948.

The stock’s dimensions are remarkably “modern,” as I discovered when I raised the Fox to my shoulder and had that electrically epiphanic moment when I realized I could shoot this gun. I thought back to those people, all now deceased, who shared their memories of hunting with Aldo Leopold. People like Drs. Frederick and Frances Hamerstrom, the eminent prairie chicken biologists whose improbable journey from the salons of Boston to the hardscrabble farms of central Wisconsin is recounted in Fran’s memoir, Strictly for the Chickens.

“He was a crack shot,” recalled Fran (who carried a Parker herself), “and he was always ready. The gun was like part of his body — it just followed his eyes. He was extremely graceful and elegant in the field, and the game just seemed to come to him. We could stand in an open meadow, talking before moving to the next cover, and a drake mallard might come over. Suddenly, there would be a greenhead for dinner.

“He seemed to know in his bones where game would be.”

Fred (“Hammy,” to those who knew him), echoed this: “He didn’t waste time thrashing around in the brush. He knew exactly where to go, and how to get there most neatly and efficiently …”

To read the rest of this story, pick up a copy of Sporting Classics‘ Guns & Hunting 2015 issue or subscribe to the magazine today!

Images courtesy of the Aldo Leopold Foundation