“Many people have the basic ability to draw what they see. All children love to draw. It’s just that most lose interest in it for whatever reason. But I never did. I fell in love with art and the outdoors when I started fishing the stream by my house as a kid, and I’ve never lost that feeling.”

Al Agnew calls it “Kamikaze trout fishing.” Agnew, the talented and prolific painter, hooks up with a few pals each year in Livingston, Montana, the primo access site for some of the country’s greatest trout water. After meeting a resident guide friend, Al and his buddies fish with maniacal zeal for as long as their work schedules and wallets allow.

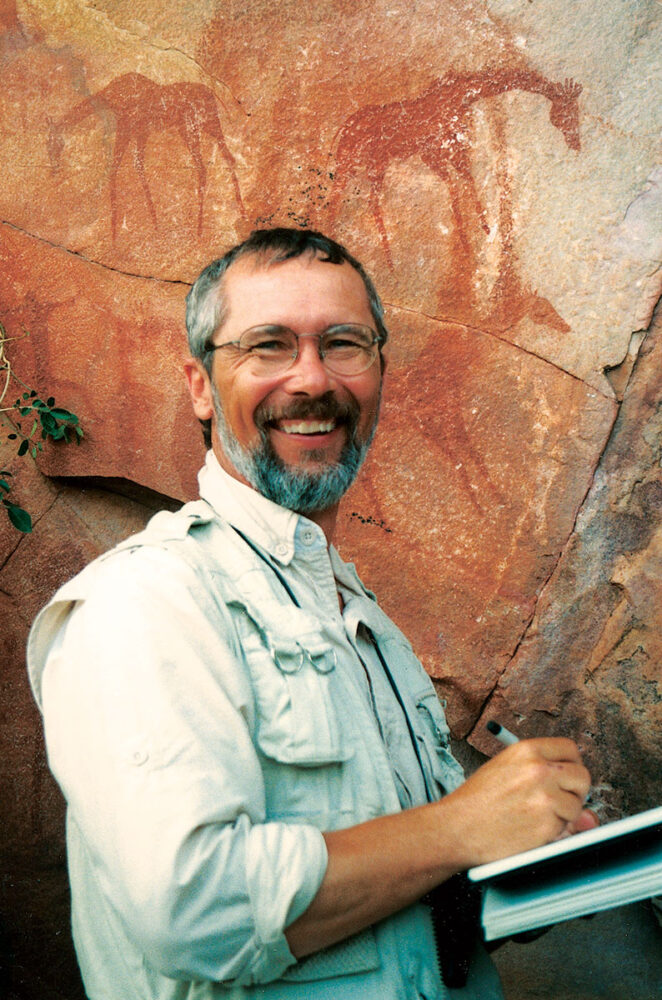

Al Agnew sketches petroglyphs in the wilds of Africa.

“From Livingston it’s an easy drive to so many wonderful streams,” Al says. “One year we hoped in a drift boat before dawn and started down the Bighorn River. We didn’t pull out until a couple hours after dark, and we were fishing the whole time. We don’t hit the Bighorn every year, though. We just put ourselves in the guide’s hands and go where he knows the trout are biting. It might be a little stream up in the mountains, it might be the Yellowstone River. All that matters is that we’re fishing and we go at it pretty hard.”

The annual Western blitz is a much-anticipated event for Agnew, who welcomes it on two levels. First, he’s been a diehard angler since age eight, when he began making solo ventures to a smallmouth stream that flowed only a mile from his home in southeastern Missouri. Second, and perhaps more importantly, it’s one of the few outdoor adventures in which Agnew allows himself total immersion, leaving thoughts of light and shading and composition and reference-gathering behind him. “That can be a very hard thing for me to do,” Agnew admits. “It’s the curse of being an artist. Sometimes I wish I could turn it off, but I guess it’s a good thing, too.” A good thing, indeed.

While resting his painter’s eye might make his outdoor adventures more enjoyable, Agnew’s keen perception and relentless work ethic have kept him among the country’s top painters; no mean feat in an art market that’s grown decidedly soft. “One of the things that I believe has helped me is my diversity,” he says. “I paint fish and mammals and birds and enjoy them all. I focus on whatever interests me at the moment, and painting such a variety of subjects has given me broad exposure. I’m also fortunate in that my career has gone well enough that now I can pretty much paint whatever I want.”

The luxury of such freedom isn’t lost on Agnew, a former public school art instructor who found himself at a crossroads in his career nearly twenty years ago. “I’d taught K-through-12 art at a small school for seven years and I was getting kind of burned out,” Agnew allows. “Teaching can be so rewarding, and it can also be so frustrating. Anyway, I’d reached a point where I knew I didn’t want to do this for the rest of my life and I was kind of looking around, thinking maybe I should go back to grad school and teach at a higher level. But I was also a hobby painter, and in 1984 I decided to enter the Missouri trout stamp contest. When I won it, I figured, Well I’ll just do that. I’ll be a full-time painter.”

Rush Hour

Al chuckles at the memory of his youthful optimism. “Trout stamps are not the money-makers that duck stamps are,” he says. “So there wasn’t a big, immediate payoff, but winning that first contest got me recognition. It was a start.” While his wife Mary worked as a registered nurse and provided steady income, AI devoted himself to the easel and went on to paint thirteen state conservation stamps, depicting everything from saltwater fishing to non-game species. The stamp wins showcased his talent and versatility, and as AI’s career flourished, Mary became his business manager and tireless promoter. The pair live on a forty-acre wildlife haven outside scenic and historic Ste. Genevieve, Missouri. Though he’s traveled widely, the Show-Me state native is most content at home.

“I can’t think of anywhere else I’d rather be,” he said during a phone conversation one brilliant October day. “Our house sits next to a gorgeous oak/hickory forest full of deer and turkeys. We’ve identified 136 species of birds on our property. We have a small spring and a pond we’ve stocked with bass and bluegill. As I’m talking to you I’m looking at our woods and the fall colors are just fantastic. It’s like a study in light and color. The leaves on just one tree are amazing; some are in shadow and are blue and cool, others are in full sun and white-hot, and of course the warm reds and yellows of those that are lit just right. I can carry images like that into the studio with me and start a painting.”

AI doesn’t paint strictly from memory, of course. He’s a devout photographer, plein-aire painter and pencil-sketcher. “Each is a tool with unique applications,” he says. “I use photography for research and reference, especially on wildlife. Sketching is a nice way to capture detail that’s hard to pick up with a camera. For example, if I’m watching a lion sleeping and want to have a detailed reference on the underside of his paw, I sketch it. I love to paint outside when I want to capture the colors and values of a particular scene. It’s an excellent way for me to get a landscape just right.”

The Road Less Traveled

Back in the studio, Al starts a painting by making a series of thumbnail sketches to flesh out an idea and a design. “I may spend up to a fourth of my time on a painting just on coming up with a pleasing design,” he says. “Once I’ve arrived at something that I like, I transfer the sketch onto the painting surface. Most of the time I’m working on larger pieces, which is why I’ve switched from watercolors to acrylics and oils; you’re restricted to using paper for watercolor, and the sizes available are very limited.”

Al also abandoned watercolor because he found himself overworking the medium. “Most people think that every watercolor is a loose, impressionistic work,” he notes. “Actually, watercolor is the easiest medium to work in fine detail, and I was really letting myself get bogged down in that. I think it’s a natural progression for artists to want to loosen up and get more impressionistic. I’m not convinced that loose is better than tight, but what I’d like to do is get more efficient; I’d like to include detail, but make the painting look like I haven’t spent hours agonizing over it.”

Achieving such an effect can be a challenge for Agnew, especially when he’s painting avian subjects. “Birds have multiple levels of detail like no other creature,” he says. “Feathering patterns differ according to the area of the body. There are details of line and color – and sometimes multiple colors, like you see on a rooster pheasant – that are unique to each feather. And then there’s iridescence, which can be a huge challenge to portray well in itself. To me, all these factors work together to compound the challenges of painting birds well. Yet I still love to do it!”

Into the Night

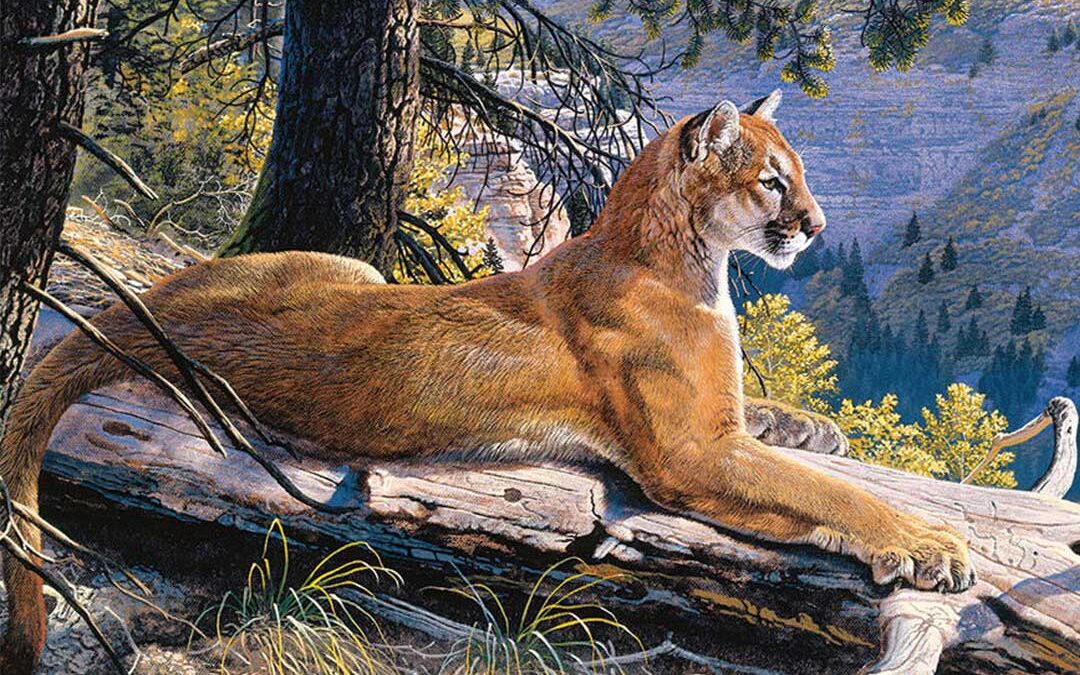

Fish and mammals present less of a hurdle for AI, who admits his life as a sportsman has had a huge impact on his art. “I know there are wildlife artists who don’t hunt and fish, and I don’t begrudge them that at all,” Agnew says. “But I believe that being a hunter and fisherman gives me an edge. Both pursuits require you to be very patient and observant to be successful, and you’re outdoors in a wider range of weather conditions than most non-hunters would be willing to endure. As a result, I think my familiarity with my subject matter is much greater; I don’t paint animals in places they wouldn’t be, and I don’t portray them doing things they wouldn’t be doing. Also, I love to paint predatory animals like coyotes, wolves and cats. Being a hunter, I feel I have better insight into their behavior than a non-hunter would.”

Fishing – particularly river fishing – remains as much a passion for Agnew as it did when he was a youngster making trips to his favorite bass stream. “Rivers are a major attraction for me,” Al says. “It’s hard for me to articulate how I feel about them, other than to say that they are, for the most part, gorgeous, natural settings with very few people in them — though it’s hard to say that about the Yellowstone River in July! I guess my favorite type of stream-fishing is for smallmouths, though I love to fish for anything in moving water.”

Agnew has dozens of excellent smallmouth streams within an easy drive of home; clean, clear, quick-flowing rivers where, on a warm summer day, he may catch 50-100 fish on spinning lures he makes himself. “I make spinnerbaits and buzzbaits, but my favorite is a shallow-running crankbait I carve out of whatever wood is handy. I paint them myself, of course; I’ll use a paint brush on just about anything but the house!”

Confrontation – Whitetails

While few wildlife artists portray finned subjects, Al dove into fish art long ago. “Traditionally, prints featuring fish have not sold very well,” he says. “But when Hadley House printed my first one several years ago, it sold out fairly quickly and I was able to follow up with others. One thing that’s struck me as odd is that bass prints tend to sell better than those featuring trout.”

An ardent and enthusiastic hunter, Al has painted everything from the turkeys and deer living near his home, to western and African species. “I spend a lot of time bowhunting for whitetails around here,” he says. “There’s a bachelor group of bucks living on our property that includes a couple of pretty nice ones. Turkeys are common. But probably my favorite is bow-hunting for mule deer and elk out in Colorado. Working a bugling elk is like turkey hunting times twenty! I’ve never been able to kill one with my bow, despite having them only a few yards away. If you could only capture that excitement in paint!”

Sixteen Mile Creek

Capturing excitement is something that Al strives for in each work. “More and more, what interests me is portraying my own [sporting] experience,” he says. “I think an artist is at his best when he does that. It’s why I’ve never had any interest in painting things I haven’t seen myself. I’m a stickler for detail, and before visiting an area for the first time, I’ll research the geology and terrain. I love maps, so I get the best ones available and study them to learn as much as I can about the landscape. And knowing the geology in the region I’m visiting helps in understanding the rocks and landforms. Having that knowledge before I leave frees me to concentrate on the wildlife I’ll see on the trip itself, as well as the effects of light on everything.”

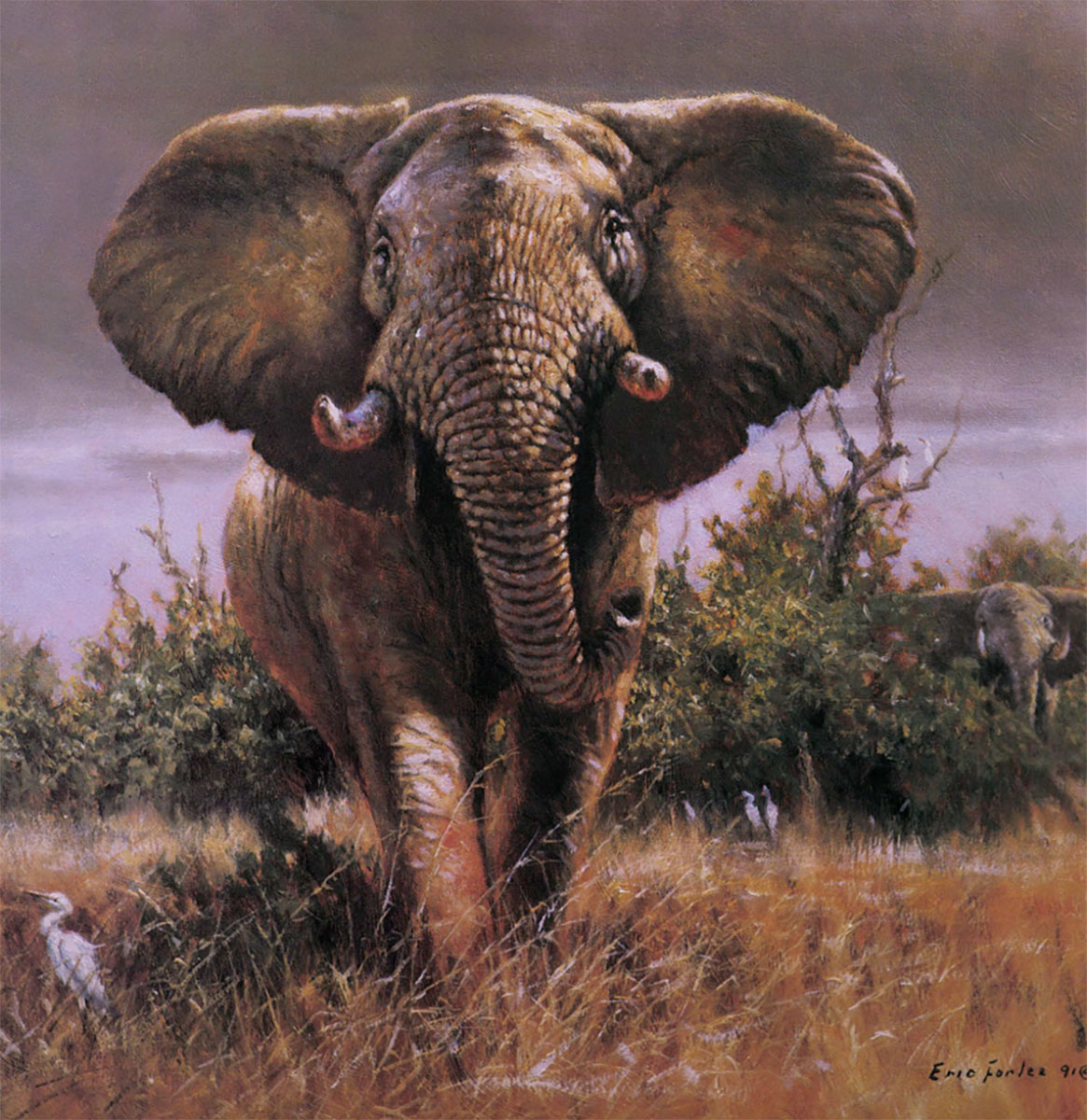

Light is one of the most important aspects in depicting nature, and nowhere is it more spectacular than in Africa. “I’ve visited three different countries in Africa, and I agree with those who say it is a life-changing experience,” Al says. “Nowhere else on earth you can see such large numbers of animals in unspoiled settings, but as an artist I’m equally drawn to the quality of light in areas relatively untouched by industrial pollution. It’s a bittersweet experience, because you can also see the effects of overpopulation and poverty once you leave the game reserves. But there is something indefinable about Africa. It’s unlike any place else I’ve ever visited.”

Sunlight

Al’s interest in wild places has led him to “pull back” in many of his recent paintings — to depict more landscape and devote less detail to the creatures themselves. “I’m more interested now in portraying the wildlife as part of the landscape, rather than doing portraits of animals. It’s the same with my fishing scenes. I just completed a painting of an eastern trout river, and there is a fisherman in it, but he’s only a small part of the scene. By leaving out detail in the angler, it allows the viewer to imagine himself in the setting.”

It’s not hard to imagine Al Agnew putting himself in such a scene as he stands at the easel day after day, adding color and detail, light and shadow, to the paintings that depict places he loves so dearly. “I don’t really believe that raw talent has much to do with being a successful painter,” he says Sincerely. “Many people have the basic ability to draw what they see. All children love to draw. It’s just that most lose interest in it for whatever reason. But I never did. I fell in love with art and the outdoors when I started fishing the stream by my house as a kid, and I’ve never lost that feeling.”

This collection of 22 stories set on fabled waters from Alaska to Baja confirms Scott Sadil’s reputation as a writer of literary fiction in the best sporting tradition. The stories capture the beauty of wild fish and the waters and landscapes where we find them and go beyond the fishing to explore relationships—between parents and children, husbands and wives, siblings, lovers, and friends—the real life situations that evoke the same win-lose drama played out between anglers and their prey. A master of language and sophisticated storytelling, Sadil brings a warm-hearted appreciation to the graceful messiness of human lives, especially the moments—sometimes humorous, always intimate—when we’re hooked to something we feel certain we care about more than anything else in our lives. Buy Now

This collection of 22 stories set on fabled waters from Alaska to Baja confirms Scott Sadil’s reputation as a writer of literary fiction in the best sporting tradition. The stories capture the beauty of wild fish and the waters and landscapes where we find them and go beyond the fishing to explore relationships—between parents and children, husbands and wives, siblings, lovers, and friends—the real life situations that evoke the same win-lose drama played out between anglers and their prey. A master of language and sophisticated storytelling, Sadil brings a warm-hearted appreciation to the graceful messiness of human lives, especially the moments—sometimes humorous, always intimate—when we’re hooked to something we feel certain we care about more than anything else in our lives. Buy Now