The watch says 4 a.m., plenty of time for warming up, coffee – the usual morning ritual. I have to smile when I remember that the bathroom isn’t down the hall, it’s out the door and across the creek on that flimsy plank footbridge, slick as a boiled owl. Then my reward will be a couple of splinters I can’t reach from the rough-sawed box with a triangular hole adorned with a fresh coat of new snow from the crack in the back wall of the privy. I meant to fix that last summer. Damn.

The coffee pot is steaming when I get back and the bacon is starting to sputter in the black skillet, the one Dad used before I was born. The Fisher is huffing like a New York spinster fighting off a hot flash and the cabin is warm, the smells awaking memories from 40 deer seasons: bourbon, Alan’s Winston’s, wet leather, Jimmy’s God-awful feet. I imagine I can see them both sitting in the glow of the lantern, laughing at an old man trying to be a boy again.

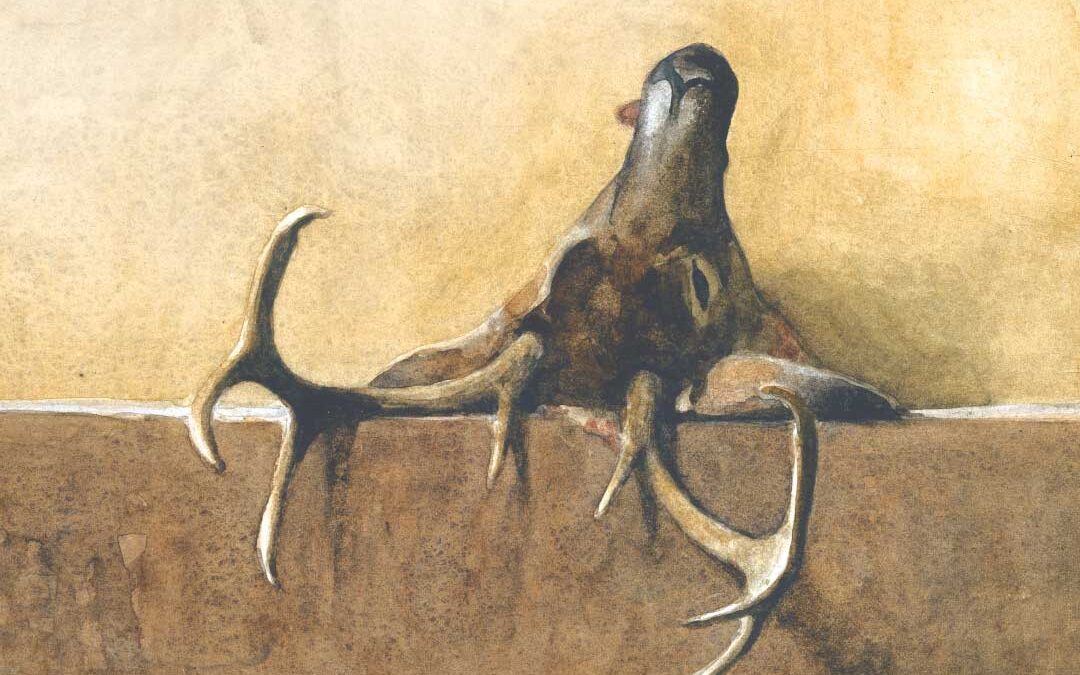

Painting by Robert Westly Amick (circa mid-1930s) – courtesy Robert Sakuta

The clothes go on slow, the boots cinched up tight. Didn’t have this Gore-Tex and Thinsulate back then, just longhorn underwear and jeans. How did I ever stand the cold? You had to drag me back in the cabin at dark; I was the first one out in the morning and the last one back at night. I’ve never been able to explain why. It just always had to be that way.

My pack is loaded with the water bottle, billy can, a packet of coffee and lunch, the short-legged stool, drag rope, poncho and a couple of garbage bags that with luck will hold meat today and garbage another time.

“Carry a garbage bag,” Dad used to say, “a wet butt means a short deer hunt.”

I’ve got the little stool now but he was right; he gets smarter every day and he’s been gone 19 years.

I look at the guns in the rack. The 788 with the good scope, the 1893 with the long octagon barrel, the .300. Today it will be the Marlin, I think as I take it down, just for you boys. For old times’ sake.

The .30/30 cartridges slide into the magazine as slick as they first did in 1904 when some other unknown hunter owned this rifle; what I wouldn’t give to know who and where. Maybe it should remain a mystery; their secrets are for them alone. We’ll make our own memories today.

There is enough moon that I don’t need the flashlight, what with the snow cover, and the walk up the mountain is steep and long with frequent stops. The exertion warms me, yet it reminds me that when I cool off later on my stand, my damn knee will start to swell and my elbow will stiffen. Piss on ’em; they’re too far from my heart to kill me.

It takes just over an hour to ease my way up through the big timber to my stand under the High Rock. As I kick back the snow and frozen leaves, I try to remember how many deer I’ve killed at this spot. It first became my rock in 1970; it was my rock when my young raven-haired bride joined me here in ’78; when the boys sat with me after I carried them up here on my back in ’90.

I still carry the perfect white quartz arrowhead I found here one November afternoon, to remind me that it was someone else’s rock thousands of years ago. Tell me what you’ve seen, rock, I think as I settle against it, out of the light, cold wind. God, what you must have seen on all those fall days. Did another young man sit here with his sons before time was counted? Did another old man come here like me to kick-start that feeling of being alive, to try to defy death by dealing it? Were there buffalo on the mountain, and elk and cougars? Did wild turkeys roost in the big hollow and did the deer use this ridge like they do now? Did humans once hunt each other here?

The stars are thick through the timber above me and just as thick are the house lights in the valley that stretch for 30 miles before me. There were no lights when my great-grandfather came here, and the sight starts to depress me. But then the realization comes that the stars are still the same and that Buck Mountain is still Buck Mountain, a thought that fills me with quiet joy. You can’t have my mountain, you bastards. You’ll never get your hands on this mountain; we made sure of that with conservation easements. Go ruin something else.

To the east the stars are fading and the wind has died. Down the ridge I hear the crunching of hooves on frozen leaves, meandering, in no hurry, now digging for acorns, testing the wind, coming. Daylight is racing them to my rock. It is exquisitely painful, heart racing, each exhale freezing to my beard. The shakes are not all from the cold. Through the Zeiss glasses I can see their backs at 100 yards, see the clouds of hot breath in front of their noses, see the antlers above the briars. I can’t see the sights yet. Idiot; why didn’t you bring the scoped rifle? Would it have been too easy?

Through the glasses I see the buck prod the does in front of him with his long tines, all business, no time for idle female gossip. Move on, he commands, we must beat daylight to the thicket below the big rocks.

Suddenly his attention is diverted by a stunning young doe, mincing around him, holding him up in his haste, tempting him, keeping him in the open timber. The other does slip away over the ridge. I raise the rifle again. I can see the sights.

A young man would have hurried the shot, missed the opportunity, shot a tree. An old man has patience from experience, from hands made bloody too many times on this ground. I wait, see the good opening along his intended path, anticipate his move. A cold thumb silently cocks the hammer; a cold finger slowly squeezes the trigger. Today will be a bloody dawn.

Sitting beside the buck I can see the cabin through the timber, small and far below. Steam rises from his propped-open chest and I warm my hands over it, washed clean with new snow. I’m in no hurry to leave. I have said my thanks and goodbyes to the buck, placing a rhododendron leaf in his mouth. Two ravens protest my blaze orange hat and a fat fox squirrel scolds me for invading his living room. I enjoy a cigar as I sit, still shivering, and the elbow hurts like the dickens, the knee swollen to the size of a softball.

I scrape back the leaves, and using birch bark and twigs I kindle a small fire between my feet. The sight of the fire warms me as much as the flames. The water bottle from the pack is half-full of mush ice and the sandwich is a coaster. The billy can has a piece of coat hanger as a bail and I suspend it on a forked stick over the fire, the ice water quickly steaming, and soon a cup of coffee does for the inside what the fire has done for the outside. The sandwich gets toasted too. The sun is on me now. I can’t stop smiling.

I try dragging the buck, but even down the mountain he’s too much for me, the damn knee going twice and causing painful falls in the broken rock and on frozen ground, but I’m too damn stubborn to quit. I’ll make it to the edge of the timber or die trying.

He gets away from me on the steep slope and slick snow, passing me like a 200-pound sled, the drag rope still across my chest, and suddenly both of us are sliding down the mountain, me on my face. A 30-inch sugar maple stops us. Hard.

I forget about the elbow and the knee. Somehow, their importance has waned. I have stopped smiling.

After a bit I rise slowly, testing each body part, and everything seems to be where it should be and working correctly. Maybe I should buy a lottery ticket today.

My attention is caught by a fat grouse striding below a fallen locust. Quietly I lever a round into the Marlin and in an instant his headless body beats wings on the snow. Another grouse appears below him and now I have two to pick. Jackpot day. Not bad for old eyes, old gun, old man. A three-shot day.

I make it to the edge of the timber and leave the buck where the pickup can reach. Down slowly, side-hill, back and forth, painfully, it takes me a while to get to the cabin. When I get back to the buck, I realize I can’t load him so I tie his rack to the tailgate and pull him back to the camp, hoping he will forgive me the indignity. Here I use the truck and rope to haul him up in the maple out front, tying his horns to the limb.

I’ve moved the truck and I’m sitting on the porch, cup of coffee and a cigar in hand, when Wade shows up.

“How was your morning?” my son asks, touching the buck, looking up at the rack.

“Just took a little walk,” I answer, smiling.