She said that same thing so many times over the years that I would just smile, nod respectfully and say, “Yeah, one of these days I’m gonna trick those ol’ gobblers and drive a borrowed car. That’ll show ’em!”

She seemed to get so much joy out of ribbing me that I seldom told her about all of the magical encounters I’d had over the years, or about all of the deer I had in my sights on so many occasions. I’ve seen just about everything up on the Indian Mound except old Big Foot himself.

Not only have I seen scores of deer, but I’ve seen bobcats and coyotes. I once located a red fox den and saw its occupants sneaking in and out. I’ve seen a stray bear or two, and I’ve watched numerous groundhogs whistle from their dens, calling back and forth to their friends and mates. I watched a great horn owl being chased and harassed by dozens of angry crows. I witnessed adult red-shouldered hawks teaching their young to hunt. And once, a very old buck, an ancient warrior with a bone-white rack and very short tines that were in sad decline, walked right by me. I didn’t have the heart to shoot him. He had once been king of the mountain, and now his days were numbered. He deserved to live out whatever time he had left in quiet solitude.

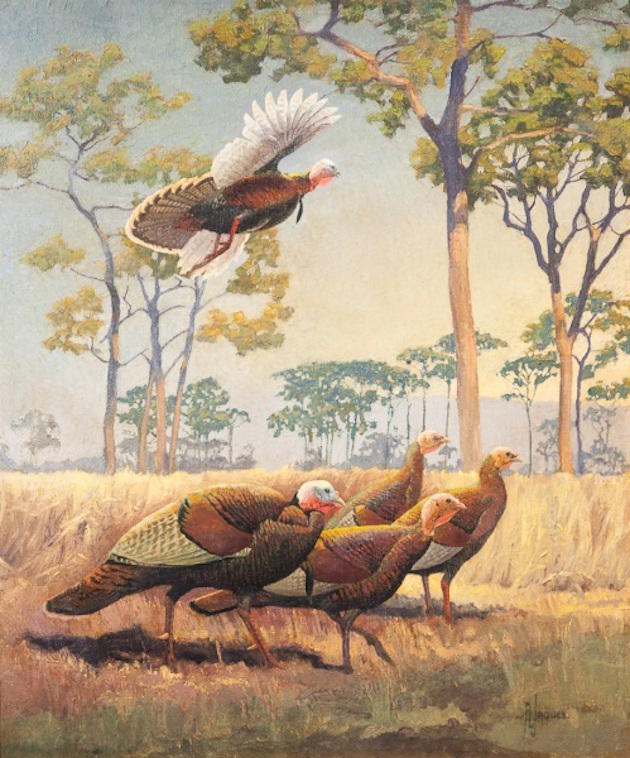

Sitting against a tree late one afternoon I watched a flock of 30 turkeys fly up to their evening roost one-by-one. They were literally only a few yards up the hill in front of me and it was like watching a slow-motion movie. They were roosting in a stand of massive and majestic white pines, some nearly 100 feet tall. About 30 minutes before dark, each bird in turn would stare up toward the limb it had chosen, begin to flap its wings wildly and suddenly defy gravity by flying almost straight up for 50 or 60 feet to its designated perch as if being lifted by an invisible hand. Then, after moving around for a moment or two and “settling” on the limb, that bird would blend in so well it would almost disappear from sight.

I never get tired of watching the Indian Mound turkeys perform their magic. They are so different from the Midwestern turkeys I’ve often watched as they fly up to much lower cottonwood trees in eastern Kansas. That is also a sight to see because of their sheer numbers, but not nearly as impressive as the mountain birds of the East. In the flat country of Kansas, the turkeys get a running start on flat open ground, almost like a heavily laden Hercules C141 transport taking off. They flap their wings until they are airborne and rise up at an arching angle and light on a limb only 20 or 30 feet off the ground.

Back East I’ve watched countless long-bearded gobblers silhouetted against the morning sky, talking to each other quietly in the tall pines surrounding the Indian Mound and occasionally gobbling their heads off as dawn was just beginning to announce a new day. And after it was light enough to see, I’ve watched many of those same birds pitch off the cold, hard limbs they had been sitting on throughout a bone-chilling night and sail down into the open valley below and into the much-welcome sunlight. Why they seldom pitch down in the woods and land a few feet in front of me is a mystery yet to be unraveled.

I’ve watched countless brilliant sunrises over the distant mountains to the east. From the top of the mound, the view of the rising sun is beyond description. I’ve seen brilliant orange azaleas in full bloom in the spring and I’ve smelled the sweet fragrance of laurel and the many flowering shrubs and plants that only the mountains can provide. I’ve often tried to imagine what it must have been like for a young Cherokee brave to witness a sensational sunrise as he was about to embark on an important hunt to some far-away mountain from the top of that sacred mound. Certainly others from the past have felt the same exhilarating sensations from the mound as the forest begins to wake up and greet a new day. The spirit is everywhere, and you can feel it.

I once sat huddled on the ground without moving for two solid hours just after daybreak watching a large flock of turkeys as they dawdled in the woods in front of me about 60 yards away (conveniently just out of range). Two big gobblers were with the large group of hens, and it was a chilling 20 degrees outside on that morning in late-March. I never put my coat on until I reach my stand, in this case, a brush blind made of sticks and branches, because the long climb up the trail from the highway makes me break a sweat if I’m wearing too many layers. All I had on that morning was a light sweater over a long-sleeve T-shirt. The turkeys appeared just as I reached the blind, and I never had time to put on my coat. It was the nicest two-hour ordeal I’ve ever had to endure!

I’ve seen poachers and trespassers and had hot-air balloons and little one-man airplanes pass over me just above the treetops near the Indian Mound. They seemed so close I could have almost reached out and touched them with my gun barrel. I’ve run off pot-smoking hippies who were trying to commune with the ancient Indians. The risk of fire is always a concern in those woods, so anyone caught trespassing is quickly escorted off the property. Once I confronted a joy rider on a 4-wheeler who was desecrating the top of the Indian Mound by doing wheelies. Didn’t he know the Indian Mound is sacred ground? Since I happened to be turkey hunting, I’m sure the sudden appearance of a man in full camo with a Benelli shotgun over his shoulder convinced that startled young man very quickly that he had better leave in a hurry and not come back. He couldn’t leave fast enough. Where do these people come from?

Once, in mid-April during turkey season, three teenage girls smoking cigarettes passed by me as they were taking a shortcut across the Indian Mound property back to the highway from the river below the mound. They passed within a few feet of the tree I was sitting against and never saw me. When I stood up and asked them to please put out their cigarettes, I’m sure they thought they were looking at Big Foot. Like the joyrider on the 4-wheeler, they couldn’t exit the property fast enough.

The land is sacred and it’s always had a strange pull on me. It holds considerable history. Although the family has always referred to it as the “Indian Mound” property, it’s really not an Indian mound at all. A thousand or so years ago a group of ancient Indians flattened-off the mountain top by bringing in dirt one small bucket-load at a time until it was perfectly flat and approximated the size of a football field. Later on, this flattened ground, overlooking a large village in the Chattahoochee River bottoms below, was used for ceremonial purposes, important meetings and no doubt social gatherings by the Cherokees. The locals have long referred to it as the “dancing grounds.” A smaller mound about 30 yards across on the western side of the dancing grounds and slightly lower in elevation was believed to contain the chief’s house. Yes, the property is sacred in many ways.

When you first cross busy Highway 17 from the big two-story house to the north that has been in my wife’s family for more than 100 years, you enter the woods taking the old logging road that has been there for decades. For me, the transformation from the noisy highway and hustle and bustle of normal life has always been like entering a great cathedral on the streets of a large city. Suddenly you leave the old world behind and you are immersed in a totally new world – a natural world of massive white pines and dainty pine needles covering the ground. The aroma of the rich earth fills your nostrils and heightens your senses.

The highway sounds begin to fade away and the woods slowly consume you. If you take your time as you quietly ascend the trail that leads up toward the mound, you will be rewarded with untold visual treasures. It is not until you get over the first ridge from the highway that you truly enter the “realm.” It is a gateway to another world. These are ancient woods, and they teem with spirits from the past. You can feel it with each step on the tender ferns that cover the ground. If you listen with open ears, you’ll hear the distant voices of the past whispering through the hemlocks. If you go slowly and take your time, you will see amazing sights. The wildlife is abundant, but you must be tuned in and receptive or it will elude you. The world across the highway is in too much of a hurry, but here time has a way of standing still.

The highway sounds begin to fade away and the woods slowly consume you. If you take your time as you quietly ascend the trail that leads up toward the mound, you will be rewarded with untold visual treasures. It is not until you get over the first ridge from the highway that you truly enter the “realm.” It is a gateway to another world. These are ancient woods, and they teem with spirits from the past. You can feel it with each step on the tender ferns that cover the ground. If you listen with open ears, you’ll hear the distant voices of the past whispering through the hemlocks. If you go slowly and take your time, you will see amazing sights. The wildlife is abundant, but you must be tuned in and receptive or it will elude you. The world across the highway is in too much of a hurry, but here time has a way of standing still.

I don’t know what possessed me to pull the trigger on that memorable Thanksgiving morning several years ago. It was time. Perhaps all of the stars were perfectly aligned on that enchanted day. When the handsome doe I had been watching stepped within 30 yards, I squeezed the trigger. Then I thanked the Great Spirit. I’ve taken dozens of whitetails and mulies in nearly 30 states across the country. This is the first deer I had ever taken on the sacred Indian Mound property. Turkeys, yes, but never more than one gobbler each year. The property is not only sacred because of its history and the many spirits that still reside in its woods, it is also a wildlife refuge of sorts. Unlike the flatlands of central and South Georgia, the mountains provide the deer with little to eat during the wintertime. Food becomes scarce. Winter is a tough time. Hunting pressure up and down the valley is significant, so the property has long served a refuge to the deer and turkeys.

I’ve seen dozens of bucks over the years. Once, three young bucks bedded a few yards apart on a ridge less than 100 away across a small hollow as I sat against a tree on the opposite ridge. They never knew I was there. I remained frozen until they decided to get up and browse off into the forest two hours later.

But on that special Thanksgiving Day several years ago, my 20-gauge sabot slug found its mark. The Thanksgiving turkey was delicious, but the venison backstraps were even better. I gave some of the meat to relatives and took some home. I’ve been back numerous times since, rifle or shotgun in hand, but never had the urge to squeeze the trigger again on a deer. Maybe someday in the future, if the stars again line up in a perfect sequence, I’ll decide to “catch” myself another deer. If I do, I’ll dedicate it to the memory of my good-natured old mother-in-law who left us a few seasons ago. Her happy spirit now soars with all the others. I have to admit… I really miss her teasing and I’ll never forget that special Thanksgiving hunt.

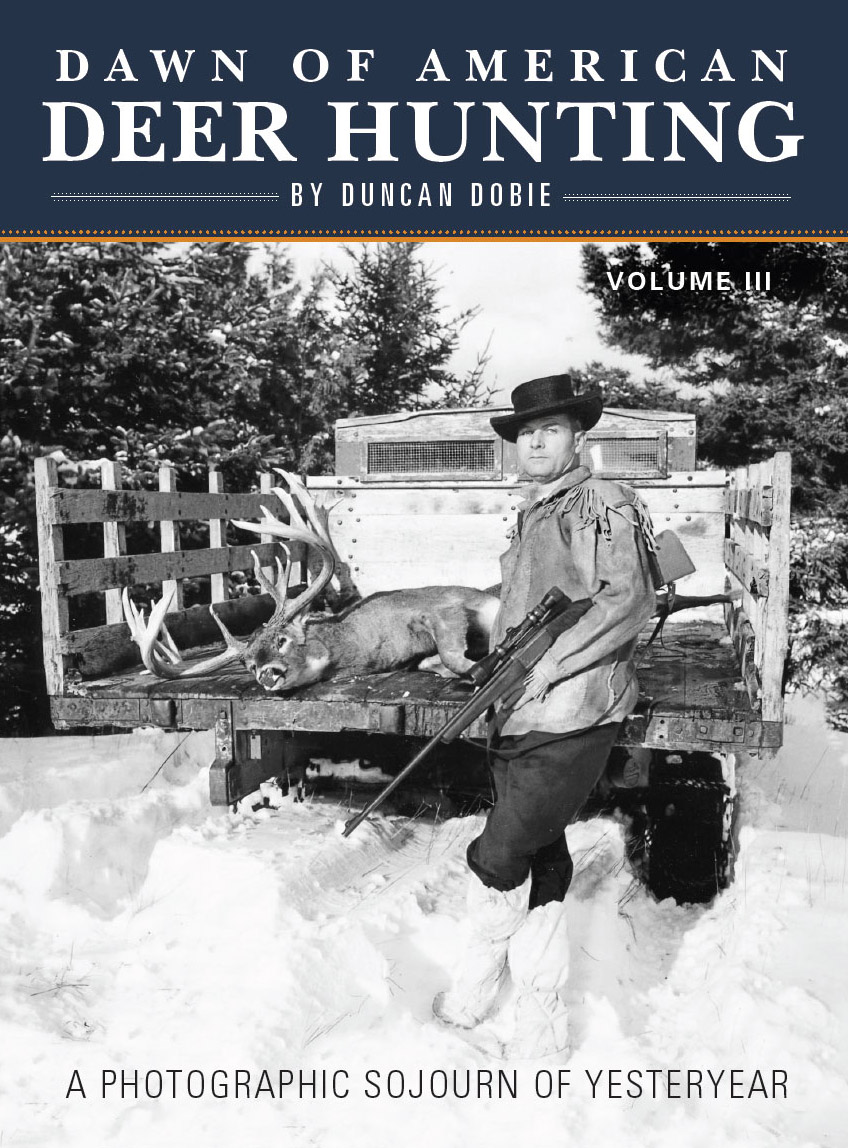

Whitetail hunting in this great land of ours is truly a “grand” obsession, and Dawn of American Deer Hunting, Volume III, will make you thankful for your own freedom to participate in and continue such a matchless tradition. The romance of the American deer camp as we knew it 100 years ago and the profound connection all modern hunters have with their ancestors and primitive hunters of the past will come to life as you turn the pages of this book. Buy Now

Whitetail hunting in this great land of ours is truly a “grand” obsession, and Dawn of American Deer Hunting, Volume III, will make you thankful for your own freedom to participate in and continue such a matchless tradition. The romance of the American deer camp as we knew it 100 years ago and the profound connection all modern hunters have with their ancestors and primitive hunters of the past will come to life as you turn the pages of this book. Buy Now