“Sir, I have waited with patience for my gun … 2 weeks was out last Monday I will wait a short time for it and if it don’t come I will either go or send. If you are still waiting to make me a good one it is all right. Please send as soon as possible. Game is plenty and I have no gun. Yours a friend. —Daniel W. Boon.”

Addressed to “Mr. Wm. Hawkins” Nov. 27, 1858, that missive made its way to St. Louis and the gun shop of Jacob and Samuel Hawken. Born in 1786, Jake had moved from Ohio to Missouri as a young man and in 1818 went into business with local gunsmith James Lakenan. In 1821 Jake’s younger brother, Samuel, (born 1792) lost his wife, closed his Ohio gun shop and joined Jake. After Lakenan died in 1825, the Hawkins brothers changed their surname to the original Dutch “Hawken.” William was Samuel’s son.

Fur trade was making St. Louis “the gateway to the West.” Staging annual rendezvous to collect pelts from far-flung trappers, General W.H. Ashley of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company funneled the fur through St. Louis. Easterners of various trades came to serve the traffic.

Early in the 19th century, settlers moving past the Ohio Valley and Cumberland Gap found small-bore “Kentucky” flintlocks (birthed in shops of German gunmakers in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania) ineffective on grizzly bears and bison. Also, prairie life was hard on rifles. On horseback, their long barrels were unwieldy; many of their svelte stocks broke. The first rifles from the Hawkens’ shop had a Kentucky rifle profile; but changes came fast. The typical Hawken “plains rifle” weighed 10 pounds with a 38-inch octagon barrel of soft iron. Slow rifling pitch in the 50-caliber bore best stabilized the patched balls still in common use. The rifle’s half-stock was generally of maple. Flint ignition was standard until about 1840. The Hawkens used Ashmore locks and their own, often with double-set triggers.

During the height of the fur trade, demand for Hawken rifles grew with their reputation for power and accuracy. When legions of fortune-seekers hied off to California gold fields in 1849, a basic Hawken rifle cost $22.50. That year Jake died of cholera. With son William, Sam tended the business. In 1858 he left William in charge to visit the Rockies, where famous mountain men had carried Hawken rifles. After working a week in Colorado mines, he returned to St. Louis. Not long thereafter William vanished in the West. Years later, a 56-caliber rifle bearing William’s name was found in Querino Canyon, Arizona.

In William’s absence, Sam Hawken hired immigrant J.P. Gemmer, who bought the shop in 1862. Sam died May 9, 1884, at age 92. The Hawken business was under Gemmer until its closing in 1915.

Most striking on one of the few original Hawken rifles I’ve seen up close is its mid-section, the stock there worn through to the barrel. Carried on its balance point across a pommel, it had endured many rough saddle miles, and probably many more in hand.

That rifle was also … well, linear. Though not as skinny as its Kentucky forebears, it had a clean, carnivorous profile, one that would be carried forward by breech-loading Sharps and Remington single-shots that scrubbed the plains of bison. Henry and Winchester lever-actions, then rifles by John Browning for Winchester held to their trim, scabbard-friendly form. Ditto later Marlins and Savages. Pistol grips on stocks then were slender, gently curved and open—and often an extra-cost feature.

Wayne’s big hand easily engulfs Winchester 94 in 25-35—an easy carbine to slip through thickets.

Slim grips, waists and fore-stocks made such rifles easy to carry in the crook of your arm. A lever rifle of that day felt alive and responsive. Up front it obeyed light finger pressure, a twitch of the palm. As if by instinct, it made incremental adjustments to track moving game. Because it didn’t fill your forward hand but was cradled by it, slight changes in aim came easily, fluidly—as the briefest hand signal corrects a well-trained Lab on a blind retrieve, or as the touch of a rein turns a veteran cutting horse.

A forend wants to be supported, not clutched. A sling tugs the front swivel against your hand, but that hand is relaxed, as it should be when there’s no sling to steady the rifle.

A fore-stock with the feel of a maiden’s wrist reminds me to hold it gently. Much thicker, and I’m fighting it. Benchrest and prone competition may justify stocks that bring Sumo wrestlers to mind.

Traditional lever rifles, and now their clones, have less mid-section bulk than bolt rifles, because there’s no magazine box. Tube magazines have drawbacks; but unless it balloons in front of the receiver, a fore-stock just broad and deep enough to wrap a magazine tube is easy for any hand to cradle and direct. An abbreviated tube (a “two-thirds” or shorter “button” magazine) doesn’t affect mid-section bulk, but it trims forward ounces, so affects rifle balance. I like the lean look it gives a barrel up front. Some hunters noted the first rifles without barrel-length magazines were less wind-sensitive, so easier to steady.

While bringing and holding a rifle on target matters, aim is but a drop in the bucket of time spent finding game. I carry a rifle for hours or days to earn a few seconds aiming. It is more companion than assassin, given its tenure at each task! The worn waist of that Hawken rifle suggested other hunters have shared that view!

Carrying a rifle for hours is mighty tiring if you carry it only one way—just as driving tires you if you keep your hands “at 10 and 2” on the wheel without a break. Walking far, and when using both hands climbing or glassing, I sling the rifle, muzzle up, on my right shoulder. On prairie or in light cover where game might appear, I cradle it with my left arm, middle two fingers of that hand under the grip or lever, thumb up against the comb nose. Threading thickets, or on a fresh track when game might be near, I hold the rifle with both hands, at the ready.

Hours into a day, my shoulder and the crook of my arm beg relief, so I suspend the rifle loosely in my right hand, wrapping palm and fingers around its waist at the balance point.

It hangs comfortably there, more or less horizontal—as would a briefcase or lunch-pail. After a while, the left hand gets its turn, but with the butt forward instead of the muzzle. That way the grip can come quickly to my trigger hand. Of course, the muzzle must not point toward a partner in front or behind!

Such a carry is natural because our hands evolved wrapped about clubs, oars and longbows, and grabbing firewood and sticks to build huts. We carry long-handled tools this way too—pitchforks, hoes, shovels, axes, garden rakes—and other items without handles such as crowbars and bales of straw. But to bear weight any distance, your fingers must be able to close, or nearly close. A cupped hand tires easily under load. That’s why a scoped rifle, or one with a protruding magazine at the balance point, is so soon uncomfortable in one hand, while an iron-sighted lever-action is not.

An alternative to horizontally dangling a rifle in one hand is letting it ride on a shoulder, muzzle up to the rear, butt cupped in your palm. Alas, you have little control of the rifle. In Africa this carry is reversed so the muzzle is down in front, hand loosely around it. A couple of historical reasons for this: Gun-bearers carrying ponderous blackpowder double rifles for explorers and ivory hunters walked in front. The rifle could be seized quickly by its grip from behind. Released by the gunbearer, the barrels were already pointed forward. Also, early big-bores had a decided tilt to muzzle. Balanced on a shoulder, the buttstock had to be brought down and toward the body for best control. Thus, angled up, the muzzles caught overhanging branches.

While modern double rifles are shorter, lighter and easier on the clavicle no matter which way the barrels point (and many professional hunters carry their own rifles), the muzzle-forward tradition persists.

What doesn’t work well in one-hand carry, at your side or over your shoulder, is a scoped rifle or one with a protruding magazine. Both keep your hand from closing about the rifle’s balance point. While a scope won’t prevent comfy carry atop the shoulder, it raises the rifle’s center of gravity so the rifle tips. A protruding box nixes one-hand carry at your side, and on the shoulder must be laid on its side.

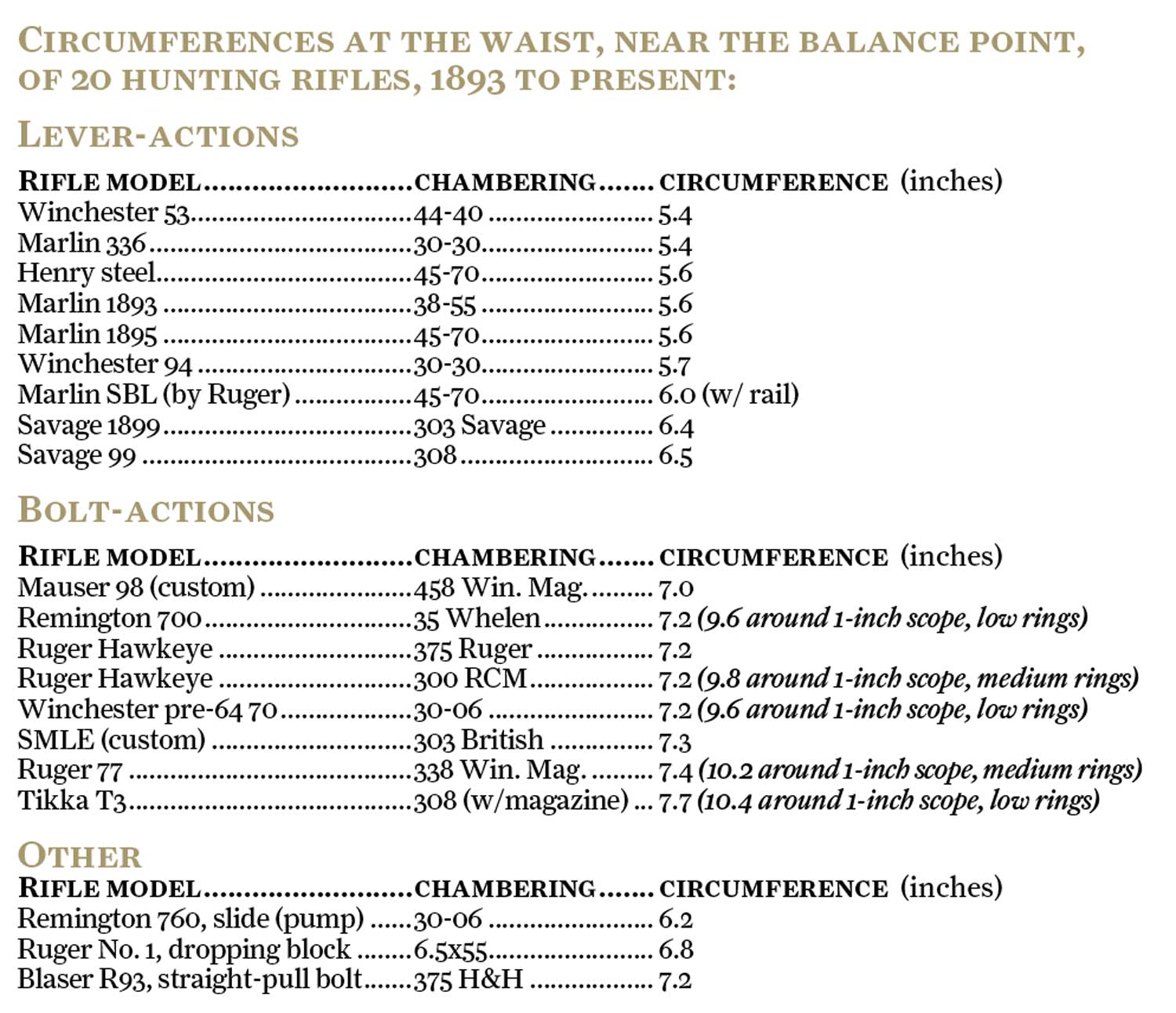

Detachable box magazines on hunting rifles leave me cold, but flush versions, polymer and steel, are improvements. Given a flush or internal magazine, how much mid-riff bulge has followed our march away from open-sighted lever-actions to scoped bolt rifles? Cloth tape in hand, I probed several sources for rifles of varying vintage.

As hands vary in size, and gloves or mittens can impede their closing about a rifle’s waist, there’s no measure splitting “alluringly slim” from “too bulky.” My hands are big enough to get in their own way—8 1/2 inches long up the center, with a 9 3/4-inch thumb-to-pinky spread. But generally, the slimmer a rifle at the balance point, the better it looks and feels to me. The 5 1/2-inch waists of many lever-actions have a maiden’s-wrist quality absent in the 7 1/4-inch middles of bolt rifles. I shouldn’t have been surprised at the measure of 1899/99 Savages, as those receivers were machined from steel blocks and held 5-shot spool magazines. Their 6 1/2-inch circumferences came in right between those of their tube-fed counterparts and modern bolt rifles. But they look and point like trimmer rifles. Kudos to Arthur Savage and his engineers!

While the rail on the Marlin SBL by Ruger adds just half an inch to the circumference of the 1895 action, it’s an angry half inch against palm or fingers, and worth removing if not needed for the rear sight.

The 10-inch circumferences of popular bolt rifles plus their 1-inch scope tubes is nearly twice that of a Winchester 94’s waist! Too much hardware to snug into my palm.

Rifles without scopes have so endeared themselves to me on the carry, I’ll often forego an optic’s advantages, even for open-country game. Some years ago, after scraping up enough lira to book a basic hunt for Dall’s sheep and moose, I checked zero on an old ’03 Springfield with a Redfield receiver sight. Its sporter stock, which I’d finished up, was of fencepost walnut but fit me well.

The Super Cub climbed into a low ceiling after dropping me at sheep camp. My guide rolled his eyes when he saw the 30-06 wore no glass. “We’ve not seen a lot of rams. Shots can be long. Wanna use my rifle?” I smiled and demurred.

Long hikes into the hills from stream-side’s landing strip were the rule; but I was in good shape and keen to find game. At last we spied white spots on black basalt far away. An hour later we were close, but the sheep had vanished. We picked our way through the rocks, glassing every few steps, lest we bump them. Suddenly, five rams clattered from behind a chimney. I dropped quickly to a sit and tried to keep the bead on the ribs of the biggest. He was quartering off at about 80 yards when my soft-nose tumbled him.

In moose country, mostly level summer-dry bog with pickets of spruce, I expected close shooting. But my still-hunting pace proved too fast. A pair of moose erupted from a thicket, high-stepping at speed toward the Bering Strait. Charitably, the bull split away from his consort just before they vanished in the ranks of stunted conifers. Antlers and a great dark hump winked through the cover as he trotted across my front at about 150 yards. I looked frantically for an opening. By great good luck, the animal slowed in the only slot that came to eye. As he turned, I fired. Then he was out of sight. I ran forward and glimpsed him again just as he collapsed.

While I still use scopes, most game my rifles have taken in North America has fallen within the practical range of an aperture sight. Scopes still have an edge in poor light and where cover hides part of the animal. But the handling qualities of a rifle that carries easily in my palm, as well as the excitement of getting within metallic-sight range, have held me off scopes entirely for my last four hunts in Africa.

Richard Browne no doubt considered scoping his Model 721 Remington bolt rifle when in 1968 he drew a Montana bighorn tag. He was keenly aware this might be his only chance to hunt a bighorn. But he gave the rifle little thought as he embarked on long scouting hikes and tapped local sources for any information on sheep. He mapped sheep sightings by other outdoorsmen.

Browne’s prep paid off when, not long into the hunt, he intercepted a big ram. But he declined the easy shot because its wide curls weren’t quite to his taste. Too soon, fine autumn weather yielded to cold, cloudy days. Low ceilings hid the peaks. As the season raced toward its close, Browne was lamenting his decision to pass on that wide-horned ram!

Then, one December afternoon, on a sheep trail high above the Clark Fork, he descended a step in an icy cliff “by hanging onto the top of a limber Douglas fir.” He was barely back on his feet when rocks clattered behind him. He spun about to see a huge ram bounding up a slide. Flinging the 270 to shoulder, Browne fired just as the animal crested at 80 yards. “The ram lurched [and] tumbled head over heels…. I dropped my rifle and ran ahead with the crazy idea of trying to stop that plunging body.” He came to his senses as the heavy beast rolled and bounced over a lip. Fearing the worst, Browne eased to that ledge and peered over. Close below, a fallen tree had arrested his prize! Those magnificent horns were saved! They taped 43 and 45 inches and rank well up in the Boone and Crockett Club’s all-time records.

A less agile, scoped rifle might not have given Browne the quick shot he needed. It might even have impeded his earlier, dicey descent, as he clutched the crown of that supple Doug fir! Battalions of hunters anticipate long, deliberate pokes, only to find their chance comes at modest range—but urgently and under difficult conditions!

European hunters of traditional bent have long revered slim-waisted “stalking rifles.” Many of the finest have come from the Austrian arms-making hub of Ferlach, where the Fanzoj family has built guns since 1790. Daniela Fanzoj, who now runs the modern shop with her brother, Patrick, is quick to point out that “a magazine adds to a rifle’s length and usually to its depth. A stack of cartridges is evidence you’re unwilling to bet the hunt on one bullet. A bolt knob is a protrusion. Many hunters throughout Europe hold the purist’s view that a stalking rifle must be a single-shot, with a hinged or dropping breech.”

As stalking is a hunting style, bolt-rifle enthusiasts counter that action type is immaterial. Stalking predates not only cartridge rifles but rifling itself. Verily, the origins of the stalking rifle are hard to place. Emerging in the British Isles as well as on mainland Europe, it followed military postings of sportsmen to colonies in Africa and India. Exploits of hunters such as W.D.M Bell and Jim Corbett kept lightweight bolt-actions in the stalking rifle arena.

In his 1932 book, Big Game Shooting in Africa, Major H.C. Maydon recommended a “7.9mm Mauser Sporting Carbine” for all but heavy game. For close shots, he declared, “a telescopic sight is no attraction…. A carbine is handy for crawling through brush.” Writers then seldom cited cost differences between standard Mauser actions and hand-built single-shots; but that could be a big gulf. Little wonder that—shooting antelopes for skins and meat on colonial frontiers—hunters used small-bore bolt-actions and called them stalking rifles!

Daniela handed me an exposed-hammer Fanzoj kipplauf many decades old. Subtly engraved steel joined figured walnut as if one grew from the other. This 8×50 had been meticulously cared for. No scars, no bruises. It glowed with the warm patina of oiled hands and sheepskin. “This is an original short-rifle kipplauf,” Daniela explained. “A stalking rifle is slender and lithe, for hunting in steep places and quick shooting in forest. For each animal, the hunter chooses a specific load. It’s a ritual of respect. A stalking rifle says much about its owner….”

“Are scopes allowed?” I had to ask.

“They’re a concession to aging eyes,” she laughed. “A proper stalking rifle has iron sights.”

Few rifles produced in North America would qualify as a Ferlach stalking rifle. But some lever-actions with abbreviated magazines share the trim lines and natural pointing qualities of fine single-shots. Flat-sided, with no projections save the lever loop wrapping your fingers, these rifles slip easily into and out of scabbards. Grasp one about the waist. It’s as easy as closing your hand.