The young naturalist pulled back the tent flap and peered into the inky blackness of the African night. He was certain he’d heard something.

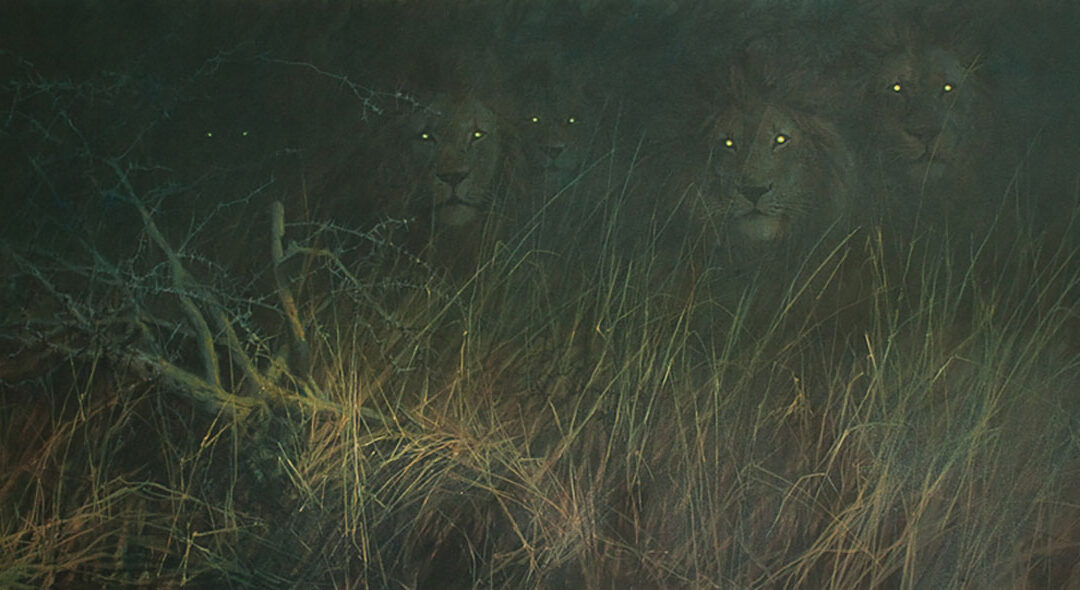

As he raised his lamp, his worst fears were confirmed. There, only a few steps away, were the glowing eyes of approaching lions. The naturalist was 34-year-old Edmund Heller, a key member of Theodore Roosevelt’s East African safari.

In early 1910, Heller had set up a small temporary camp along the Upper Nile in the Congo’s Lado Enclave, whe re he would spend his time hard at work cleaning and preparing skins. The main Roosevelt safari was elsewhere in the Lado (which became part of northern Uganda), but Heller was on his own in a camp that included three tents. In fact, TR’s caravan was several miles away, and unbeknownst to Heller, they were battling a fire that was threatening their camp. Soon Heller would be dealing with his own drama. Heller occupied two tents, working in one and sleeping in the other. His pagazi (porters) shared another tent and their supplies were kept in an ox wagon.

TR and Kermit had shot two white rhinos, a cow and a calf, two days earlier, and Heller was left to deal with the skins before they spoiled in the intense heat.

Although Heller enjoyed on-the-spot skinning and taxidermy work, conditions in the Lado were grueling. A multitude of biting insects plagued the safari, so he and the other naturalists, Dr. Edgar A. Mearns and John Alden Loring, had to work quickly to preserve the trophies.

Realizing the urgency, Heller and R.J. Cuninghame, along with a team of pagazi, would bring tents and equipment out to the kill site. Then, while Cuninghame returned to the main camp, Heller would spend the next 36 hours skinning and treating the skins.

The native helpers collected a great deal of meat, which had to be preserved as food for the main camp. Heller worked feverishly, with little sleep through two long days, with only occasional assistance from his pagazi. Protected from the invading insects by mosquito netting, he could hear their constant buzzing as he toiled into the second night. Beyond the insects he could hear a chorus of lions in the distance. He secured the meat as best he could, but felt vulnerable in his little tent. He was, after all, a naturalist and not a big game hunter.

From his sleeping tent, away from the skins and carcasses, Heller peered through the flap into the jet-black African night. He knew the lions were only a short distance away when he spotted their whitish chests in the darkness. The cats seemed to be coming from every direction and it was hard to tell how many there were. They had obviously been attracted by the scent of meat.

Heller reached for his gun, but realized the futility of taking action in such a situation. He closed the tent flap and, gun in hand, sat on his cot. He could hear the pagazi muttering in the distant tent, but he knew he was really alone.

He could hear the lions’ low growls and the soft padding of their footsteps as they circled the tents. He even saw a slight bulge in the tent wall as a lion brushed past. Needless to say, Heller had a fitful night.

Daybreak finally brought relief for the naturalist, and he gingerly opened the tent flap to see many pugmarks within a few feet of the entrance. It had certainly been a night to remember.

Legends of the Hunt, is for anyone who remembers the distant roar of a lion on an African night, the welcome smell of a north country campfire, or the taste of dust as you trek through the scrub in the equatorial heat. Sir John Seerey-Lester wants you to smell that smoke, taste that dust and hear that lion when you look at his paintings and read his stories. Altogether it’s a remarkable journey – one that you will treasure always. Buy Now

Legends of the Hunt, is for anyone who remembers the distant roar of a lion on an African night, the welcome smell of a north country campfire, or the taste of dust as you trek through the scrub in the equatorial heat. Sir John Seerey-Lester wants you to smell that smoke, taste that dust and hear that lion when you look at his paintings and read his stories. Altogether it’s a remarkable journey – one that you will treasure always. Buy Now