It was a scene of primal, primitive savagery; it seemed like something out of a corrupted Moby Dick, with the inept, half-crazed Wolf in the role of Queequeg, the aboriginal harpooner who prided himself on his lethal professionalism.

Below Elizabeth Falls, where it thunders out of Black Lake, the Fond Du Lac du Nord relaxes. The river sprawls across a boulder-studded delta, braiding into pools and riffles and narrow chutes before losing velocity and spilling into a mile-wide bowl. The roar of whitewater becomes a whisper; the whisper a sigh. A tall, flat-topped esker, so perfectly and symmetrically formed that it might have been engineered by an ancient civilization, cradles this widening on the on the far side. The near shore is lower, a gradual rise through willows and alders to the lance-like crowns of spruce. They stab the sky, a medieval army arrayed to repulse the arctic weathers. Where the shorelines come together, at the north end, the river regathers itself, quickening for the rush to Stony Rapids and onto Athabasca.

Below Elizabeth Falls, where it thunders out of Black Lake, the Fond Du Lac du Nord relaxes. The river sprawls across a boulder-studded delta, braiding into pools and riffles and narrow chutes before losing velocity and spilling into a mile-wide bowl. The roar of whitewater becomes a whisper; the whisper a sigh. A tall, flat-topped esker, so perfectly and symmetrically formed that it might have been engineered by an ancient civilization, cradles this widening on the on the far side. The near shore is lower, a gradual rise through willows and alders to the lance-like crowns of spruce. They stab the sky, a medieval army arrayed to repulse the arctic weathers. Where the shorelines come together, at the north end, the river regathers itself, quickening for the rush to Stony Rapids and onto Athabasca.

Middle Lake, this place is called. It sounds Tolkienesque, but it is not a fiction. If you look on a map of northern Saskatchewan and trace the Fond du Lac’s tortuous course, you will find it, a tiny blue dot set apart, by a sliver’s width, from the massive horizontal swipe of Black Lake.

McClane fished there, Joe Brooks, others whose names were famous in their day. The journey was long and tedious — a day to Winnipeg; another day, hopscotching hundreds of miles across the bush in progressively smaller aircraft, to camp — but it was made bearable by the prospect of what awaited: Some of the world’s finest fishing for Arctic grayling. Grayling not only of extraordinary size, strength and beauty but of an uncommon inclination, hatch or no, to rise to dry flies.

I fished Middle Lake, once. Everything they said about it was true. Some 30 years later, the evening I spent there remains among the most remarkable fly-fishing experiences of my life. It stands out so luminously that I sometimes wonder if it really happened.

But that memory is tangled with another, darker one. It is impossible to separate the two. At best, if I tug carefully and deliberately, I can tease a few discrete threads — images, sensations, emotions — into focus, but then it all bunches up again and the memory of Middle Lake becomes hopelessly jumbled with the memory of the bear. We’d stumbled across it that very morning, en route to the day’s pike fishing.

Our guides slaughtered it. We watched it die.

The camp was called Morberg’s. It stood at the far northeastern corner of Black Lake, overlooking the fjord-like inlet from which the Fond du Lac debouches. The location had been chosen with an eye to the fishing for grayling and lake trout, although even then the quality of the latter was in decline. Like so many camps on the deep, infertile lakes of subarctic Canada, they’d learned too late that the appearance of abundance among this slow-growing species was an illusion, that it took only a few years of catch-and-keep to skim the cream and leave the thin, depleted dregs. The trout had not been harvested. They had been mined.

The northern pike fishing, however, had held up fairly well. The best of it was in the weedy bays and backwaters of the Cree River, which enters Black Lake at its extreme southwestern corner — nearly the entire length of the lake from Morberg’s.

The run, in a 14-foot fishing boat pushed by a 25-horse motor, took the better part of two hours. Measured by the human experience of time, it was interminable. The main body of Black Lake feels oceanic, its iron seas plunging to fathomless depths, its illimitable reach stretching so far it seems to swallow the sky. There are no landmarks; there is nothing to reckon by. There is only the drone of the motor, the slap of the water on the hull, the boreal chill of the rushing air. Time passes, yes, but without any sense of distance being closed. It is as if you are crossing the void.

Then, at last, a bump appears on the horizon. Indistinct at first, unidentifiable, it slowly resolves into a fist of lichen-painted rock surmounted by jagged firs and spruces, their rough trunks thrusting at impossible angles toward the pale light of the sun. It is like watching the approach of a ghost ship, a derelict man of war, and for reasons that are as mysterious as those depths, it sends an icy shudder of apprehension down your spine.

But then another island looms, and another and another. Suddenly the world feels familiar again, space and time reconnected and made congruent. The vague fears ebb, the expectant, anticipatory thrill of the day’s fishing welling up to replace them. You’re almost there.

That morning it was overcast. A cool mist hung in the air, not falling so much as simply condensing, like breath on glass. My father, Harlan, was my fishing partner; our guide was a stolid and inscrutable Chipewyan named Moise, a man who, in the absence of a direct question, might go hours without uttering a word. We rounded a bouldery, reed-stippled point and saw, in the middle of one of the Cree’s lake-like widenings, another boat from Morberg’s. It was circling something in the water, something moving, swimming, alive.

A bear.

Coming closer, we could make out the broad dome of its skull, the tan, doglike muzzle, the erect, almost cartoonish ears. The occupants of the other boat, a pair of jowly retirees from Duluth named Bill and Clarence, were blithely snapping away with their Instamatics; their guide, a lean, self-satisfied Chipewyan who was Moise’s polar opposite — the Wolf, I’ll call him — stood in the stem with the outboard’s tiller in his hand, hazing the bear, keeping it in open water. It did not appear especially large, as bears go, but it was large enough.

Coming closer, we could make out the broad dome of its skull, the tan, doglike muzzle, the erect, almost cartoonish ears. The occupants of the other boat, a pair of jowly retirees from Duluth named Bill and Clarence, were blithely snapping away with their Instamatics; their guide, a lean, self-satisfied Chipewyan who was Moise’s polar opposite — the Wolf, I’ll call him — stood in the stem with the outboard’s tiller in his hand, hazing the bear, keeping it in open water. It did not appear especially large, as bears go, but it was large enough.

As our boat came alongside, the two guides began to converse excitedly. Even the stoic Moise was unusually animated. I thought nothing of it, at first. But then something in their tone brought me up short, and I realized, with a kind of awful, epiphanic clarity, that this was not merely a photo opportunity for us “sports,” like easing up to a loon carrying its chicks on its back. The guides saw the bear as a windfall. The old imperatives — atavistic, tribal — were still in force.

I turned to Dad and said, “They’re going to kill it.”

The Wolf did most of the talking, and his stabbing gestures revealed the plan: He would fashion a spear.

A copse of skeletal dead spruces staked the muskeg at the edge of a shallow bay, and while the Wolf searched for one he could shape into a shaft and lash his hunting knife to, Moise took over the task of guarding the bear.

It is tempting to anthropomorphize, to say that I read panic and confusion in the bear’s behavior, that I saw terror in its eyes. But I did not. As if its stamina were bottomless, its patience infinite, the bear simply kept swimming, always pressing for the shore. There was nothing else it could do.

You may wonder why we didn’t intervene, why we didn’t put a stop to it. It was our time, after all, our money and no matter how we felt about the bear and its impending execution, the guides were still on the clock. But while I can’t speak for Bill and Clarence — although I suspect they were interested, like bystanders at the scene of a grisly accident, to see how the scenario would play out — I don’t think it ever occurred to Dad or me to protest.

Maybe we were just being chickenshit, afraid to risk an ugly confrontation — especially with the Wolf, who struck me as a man you shouldn’t turn your back on. That was probably a part of it, but the bigger part was the sense that the bear’s fate was out of our hands; that, as in classical Greek tragedy, the events set in motion were destined to run their course, irresistible as gravity. It was a course that no earthly power could alter, or prevent from reaching a final, terrible resolution.

The Wolf returned, brandishing his makeshift spear like a Masai warrior. There was no more conversation. Moise kept the bear pinned between our boat and theirs, and the Wolf stood and struck, again and again and again, seeking to drive the blade between the bear’s ribs, into its lungs. The spear was long and unwieldy and the Wolf, for all his bravado, was no good with it. Most of his blows glanced off bone or missed entirely, the blade slashing futilely at the water. But enough struck home and one went deep, extracting an anguished, bellowing groan; a sound that issued from a place that is all darkness, all black.

It was the only time the bear cried out.

I can hear it, still. And I can see the Wolf as he thrusts his spear, his eyes ablaze, his face contorted with a kind of lascivious fury. It was a scene of primal, primitive savagery; it seemed like something out of a corrupted Moby Dick, with the inept, half-crazed Wolf in the role of Queequeg, the aboriginal harpooner who prided himself on his lethal professionalism.

I can hear it, still. And I can see the Wolf as he thrusts his spear, his eyes ablaze, his face contorted with a kind of lascivious fury. It was a scene of primal, primitive savagery; it seemed like something out of a corrupted Moby Dick, with the inept, half-crazed Wolf in the role of Queequeg, the aboriginal harpooner who prided himself on his lethal professionalism.

Solemn as Puritan judges, Bill and Clarence watched impassively, Bill in his canvas duck coat and Jones cap, Clarence in his red-and-black-plaid mackinaw. Moise, too, betrayed no emotion; when I glanced at Dad, he could only shrug, purse his lips, and shake his head.

Finally and mercifully, as the knife sank one more time inside the bear, the fatigued metal snapped at the helve. The Wolf stared mutely for a moment; then, laughing like a hyena, he flung the useless shaft into the water. But the mortal damage had been done. Now — and this was the most horrifying part — we simply waited for the bear to die. We waited while its life leaked away, its blood mingling with the currents of the Cree River, this artery surging through the wilderness of northern Saskatchewan.

The guides positioned the boats directly opposite one another, orbiting the bear in counterclockwise circles like partners in a slow, sad waltz, a valse triste. The bear swam in circles also, a trickle of blight red, heavily oxygenated blood bubbling from its wounds. Most of the bleeding, of course, was internal, filling the bear’s lungs, drowning it.

Gradually, incrementally — how long it took I cannot say — the bear began to weaken. Its breath came in rattling gasps; its strokes, which had been so impressively strong, faltered. The circles tightened, the orbit decayed. The valse triste became a death spiral, a danse macabre. It felt like the descent into madness, or hell. Yet still the bear did not cry out.

And then it was over. Moise secured a line to one leg, and we towed the bear to shore. It proved to be a young boar, three or perhaps four years old. We guessed its weight at around 200 pounds. The guides dragged it to a clearing in the bush where, working briskly and efficiently — like whalers with their flensing knives — they skinned, gutted and quartered it. The flesh was the color of vintage burgundy, a dark, purple-red. They scraped out a shallow grave beneath a canopy of firs, interred the meat and hide in the cool earth, and covered it first with moss, then with logs and stones.

“Come back tonight,” Moise explained in his halting English. “Bring our rifles.”

This puzzled us at first, but then its meaning became clear: They had to maintain appearances. Despite the liberal game regulations that applied to members of Canada’s First Nations, the killing had been illicit. They had to make it look like they’d harvested the bear during a legitimate hunt, a hunt that had taken place on their own time.

This was confirmed later in the day when, as we reeled up for the long run back to Morberg’s, Moise made what, for him, amounted to a speech. “Don’t say about bear at lodge, OK?” he asked, smiling weakly. “Could lose guide license.”

Somewhere in the vastness of the Canadian wilderness, out of sight and sound of all the world save for a handful of witnesses, two Chipewyan guides had killed a bear. It had not been clean, it had not been quick. Laws had been broken. But beyond the appeasement of our own indignation, the venting of our feeble moral outrage, it was hard to see what good could come from exposing the violators. It was hard to imagine what meaningful reparations might be made, what redemption or atonement was even possible.

We promised not to breathe a word.

That evening, after dinner, we squeezed into the cab of a stripped-down flatbed truck and made the 20-minute trip to Middle Lake, jolting down a stone-and-stump-littered two-track hacked out of the bush. Our driver, Eric, was a young, white, Albertan, who’d been hired to oversee the guide staff and serve as the resident fly-fishing “pro.” He’d been under the weather — a blackfly bite on his face had gotten infected — so this would be our only opportunity to fish with him.

The road led to a spruce-ringed cove about a quarter-mile downstream from the falls, where the current slows and reeds bend languorously at its edges. An aluminum boat was cached there, pulled up on shore.

“This is big pike country,” Eric said as the outboard coughed and caught. “They hang out below the fast water, feeding on grayling. Tom McNally caught a 28-pounder here a few years ago.”

It was a gorgeous evening, almost warm, the scattered cottony clouds glowing like mother-of-pearl in the protracted northern twilight. A flock of scoters paddled up across the lake, lugging their heavy bodies low against the steep-walled esker. Eric threaded the boat upstream, found a pocket of quiet water and set the anchor. The roar of the falls was deafening; you felt it as much as heard it, reverberating in the hollow beneath your breastbone like the thump of a kettledrum.

We took several small fish on buoyant Wulffs and Humpies, the herring-sized grayling smacking our flies with such abandon that they sometimes came out of the water completely, as if they’d been ejected. We tried a few other spots in the faster water with similar results; then Eric dropped the boat to a place where the water was deeper and less broken, a pool with a dark, Sophoclean clarity. I switched to a standard Adams — there was no discernible hatch — wiggled some slack into my cast, and landed the fly in a seam that flowed as black and slick as oil.

The Adams disappeared in a boiling rise, and I was fast to a fish that bent the rod to the cork before making a series of those graceful, arching leaps its tribe is famous for. Changing tactics after its aerial display, it stayed down, pulling hard and using the heavy current to its advantage, putting the lie to the conventional wisdom that the Arctic grayling is all show, a flashy fighter that starts fast but tires quickly. This fish battled with the conviction and resolve of a smallmouth bass, and when Eric finally slipped the net under it I gasped at its size.

“About three pounds,” he said, matter-of-factly. “Maybe a little more.”

Its beauty staggered me. The grayling was midnight blue, almost black, but with a subtle, shimmering iridescence that gave it a holographic quality. The skin seemed to have depth, as if another dimension, another universe, lay just beneath the surface, visible but forever out of reach. A band of neon-bright fuchsia tipped its eponymous, sail-like dorsal, which in turn was daubed with pink spots, stretched and elongated like bubbles in a lava lamp.

But there was something else: When I held the grayling for a picture, it vibrated like a plucked string. My hands tingled; I had the sensation that I’d come in contact with an electric current. Of all the fish I’ve handled in my life, only the grayling of Middle Lake felt like this — so palpably alive, so perfectly embodying their environment, the very water incarnated and made flesh.

I lost count of the grayling I took from that pool. The supply seemed inexhaustible. As long I got a drag-free float — the intervening currents were tricky — I rarely went more than three or four casts without a hookup. None of the fish were small; all of them fought with astonishing energy. It was everything I’d dreamed “wilderness fishing” would be.

It was almost enough to make me forget the bear.

And in fact I did forget, my mind swept clean. The whole of my consciousness focused on the grayling, immersed in the moment. I forgot until Eric, to whom fishing of this caliber had become the norm, piped up. “I was talking to Bill and Clarence at dinner,” he said. “They mentioned that you saw a bear this morning, down on the Cree.”

Nothing in his tone suggested it was anything but an offhand remark, an interesting tidbit to flavor the conversation. Dad and I exchanged the briefest of glances, just making eye contact, and I said, “Yeah, we did. It was swimming across one of those wide spots. Moise said that he and the other guide might go back and try to hunt it.”

“Huh,” Eric snorted. “I wonder how they think they’re going to do that. It’d be a miracle if they ever saw it again, in this country.”

“I don’t know,” I said, working out line for another cast.

I never returned to Morberg’s, although I heard that within a couple years of my visit they no longer made their guests take the long boat ride to the Cree River. Instead, they sent the guides ahead, and flew the fishermen there in floatplanes. But they were merely forestalling the inevitable. The camp has been abandoned now for many years, its buildings ruins in the bush, its stories lost on the keening winds.

I never returned to Morberg’s, although I heard that within a couple years of my visit they no longer made their guests take the long boat ride to the Cree River. Instead, they sent the guides ahead, and flew the fishermen there in floatplanes. But they were merely forestalling the inevitable. The camp has been abandoned now for many years, its buildings ruins in the bush, its stories lost on the keening winds.

Except for this story, which I have carried for 30 years, searching for the words to tell, the words that would help me find the way back to Middle Lake.

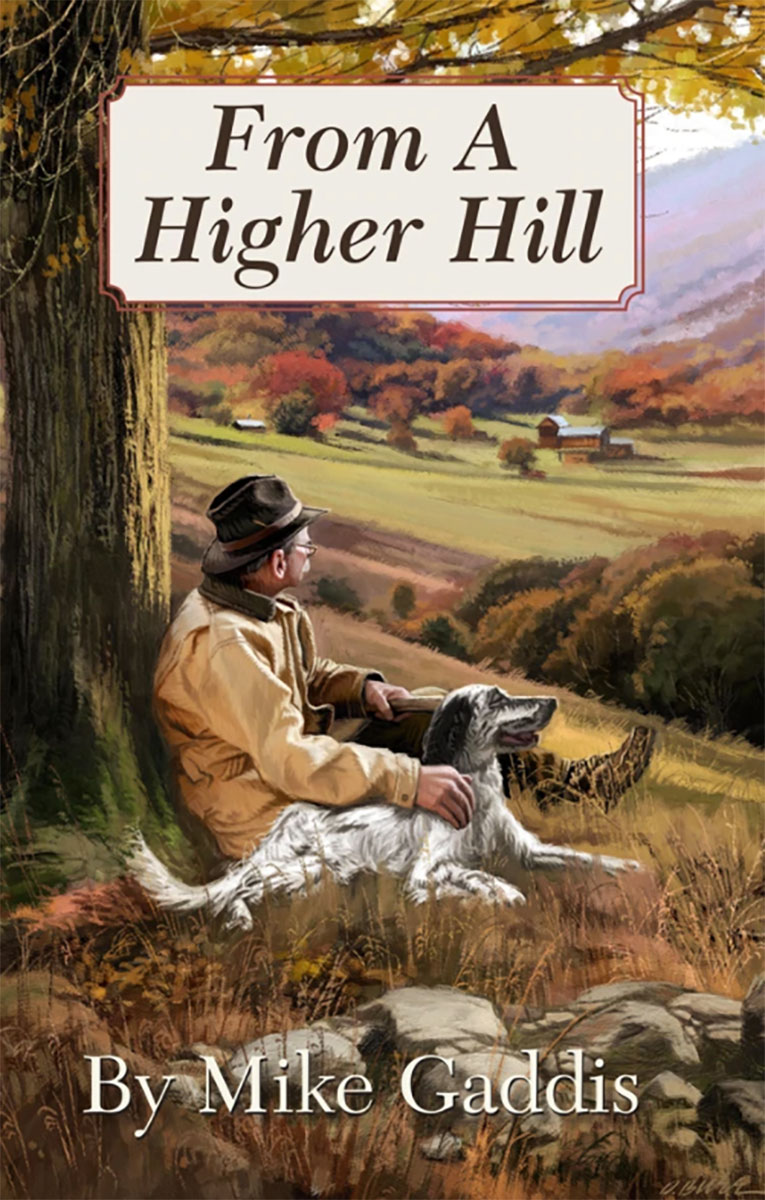

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand. From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand. From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now