I was sentenced to Chester Elementary School for six long years along with about 180 other unfortunate inmates. I wasn’t exactly sure what terrible offense I had committed against my parents to warrant such a harsh punishment, but I tried to serve my time with quiet dignity.

Chester School was located far out in the country among cornfields and close to the Horicon Marsh Wildlife Refuge in Wisconsin. On three sides of the rectangular property stood a six-foot-high fence, leaving only the front of the school open. The fence stood as a deterrent to any that might be thinking of a mad dash to freedom.

The list of crimes and punishments at Chester was long, but topping the list was the Thou shalt not leave school property rule. It was so drilled into our impressionable young minds that I know of no confirmed cases of a student ever violating it. Oh, sure, there were always the rumors. The kid that suddenly stopped coming to school and nobody knew why, but nothing substantiated. The rule was such a big deal that no punishment was even listed for it. It was left up to our imaginations as to what horrible consequence our captors could devise.

By the time I entered the third grade, I had found a best friend. His name was Larry, and together we would pull off the greatest and most daring caper in the history of Chester Elementary. It would be known as the wild goose incident, and decades later dozens of individuals who never even attended the school would boastfully claim to have been there when it happened.

Night Flight by Terry Redlin

It all started on a crisp fall morning. Larry and I were hanging out in the back of school discussing the merits of Daisy air rifles versus Crossman. School had yet to start for the day, and I was in mid-sentence about the advantage of the Crossman’s cocking mechanism when my eyes caught some movement off school property. On the other side of a field of freshly picked corn, three goose hunters were spreading out along a fenceline. I poked Larry in the ribs and pointed them out to him. We both watched in silence, waiting excitedly for the inevitable. Geese were landing all over the field. It would only be a matter of time.

In just a few minutes, a small flock circled low over the waiting hunters. I saw several geese crumple in midair before I heard the shots. Three dropped to the ground, two got away untouched, and one locked its wings in a long glide right over the school. The glider was wounded in the wingtip by the way it bent straight up.

“I know those guys aren’t going to find that wounded goose,” Larry exclaimed with a tinge of excitement in his voice. I knew by the look in his eyes what was next. It was the same look in my own eyes.

“Did you see where it went down?” I asked.

“Got it,” Larry said with much confidence in his voice.

“I think I got it spotted, too,” I calmly replied.

What we were considering was pure suicide. There wasn’t even a moment of hesitation on our part, and consistent with most of our adventures, there was not a single thought given to the possible consequences, either.

All the inmates got a mid-morning recess of 20 minutes every day—20 minutes to breathe fresh air and feel the sun on our faces before our captors herded us back into the bowels of the school. It was during this break that we finalized our plan. We chose to initiate our covert operation over lunch because we got a whole 45 minutes to eat and play before math in the afternoon. That should give us enough time.

It took some work on my part to convince Larry to be the runner. His job had the most glory but also the most danger. After all, he would be the one going over the wall. From my perspective, he had less to lose and was a little faster than me.

I was still dealing with the wrath of my dad from the last incident, which involved a salamander that somehow escaped my custody on the bus. It managed to crawl up on the leg of our female bus driver, causing a lot more excitement and commotion than you would think a small amphibian was capable of. Fortunately, Slick, as we named him, was relatively unharmed, but the bus driver quit on the spot, and my father got a phone call from the school that evening—a child’s worst nightmare.

Larry was a few months older than me and had led a good life. I had much more to live for and couldn’t handle another blotch on my already well-blotched record so soon after the salamander affair. My job on this operation had the least amount of risk but was still vitally important. I would be the lookout.

Young Boy Studying by Harold Anderson – Courtesy Heritage auctions/ha.com

By the third grade, I knew much about the inner workings of Chester School, and I put this knowledge to good use as we developed our strategy. At lunch, we were dismissed with our class and teacher to the cafeteria. It would take about ten minutes to eat, and then we would have about 30 minutes of free time.

Our plan called for Larry and I to fall behind the class on our march to the cafeteria, then slip away unnoticed. This would give us about ten extra minutes to get over the fence before the rest of the inmates began coming out after eating. Every recess had a guard on duty, and that day it was Ol’ Lady Brown’s turn. She was the meanest of all the prison guards. There was a rumor that she even made a parent cry once.

It would be easiest to go around the fence at the front of the property, but our captors ingeniously placed the principal’s office, with its large window, in the front of the school. There was no way we could get past the warden’s eagle eyes. We would have to go over the wall, which was a difficult feat with the fence being six feet tall and you only four feet.

It would take teamwork to get Larry over the top, and we chose to do it in seclusion behind the storage shed. Once over, Larry would have to cross 50 yards of open ground before he reached the cover of some trees. This is where his speed would come in handy.

I bent over, and Larry used me and the wall of the storage shed to wriggle and pull himself up to the top of the fence. He hesitated just a moment before plopping down on the other side and then sprinting across the no-man’s land as fast as his Pro Kedds would carry him. I held my breath until he disappeared into the small patch of trees.

As he ran away, it occurred to me that he wouldn’t have me or the wall of the shed to help him get back over the fence. Once again, I was glad we decided that Larry would be the one going over the wall, even if most of the glory would go to him later. I was never the type to crave glory, anyway.

Larry was in the trees just moments before Ol’ Lady Brown emerged from the school with a swarm of first-graders around her like a mother hen with her chicks. First-graders; how I despised them. That made 35 more pairs of evil little eyes on the playground. They enjoyed nothing more than tattling and were forever getting us older kids in trouble, usually throwing in some tears to further incite the wrath of the warden.

I lost sight of Larry for a tense ten minutes, and I wondered if he would find the wounded goose. We had the spot marked well in a small island of marsh grass, but anything in there would be difficult to find, and the bird would try to hide and make it even harder. I didn’t like the wait.

The pressure built as it got closer to the end of our lunch break. The bell signaling the inmates to return to their cells was about to ring. Ol’ Lady Brown was circling closer with each lap around the school. Then the bell suddenly went off. There was an immediate commotion as a hundred screaming kids all made for the school in one mad dash. Like a Pavlovian dog conditioned by three years of bell-ringing, I made for the school door like the rest of the masses.

But then I stopped and looked back to see Larry running for all he was worth with the goose tucked under his arm like a football. I waited for someone to notice him, but miraculously no one did, not even Ol’ Lady Brown. She was bringing up the rear, herding all the prisoners ahead of her like a shepherd driving sheep.

I found my legs carrying me back toward the fence, and I arrived at the same time Larry did. He tossed the very much alive goose, wrapped in his jacket and tightly bound by his shoestrings, over the wall to me. Only the goose’s long neck and head were sticking out. Larry clawed at the fence and, with much groaning, managed to pull himself to the top and then plop back down on my side.

I took the bound goose and stashed it in the over-turned sandbox as we sprinted back to class. By now we were the only living souls still outside the school, and since elementary students are herd animals by nature, it was a scary and vulnerable feeling being separated from the group like that.

Mrs. McBride bought our made-up excuse for being late, but not before she gave us a long hard look. I’d seen that look melt the toughest kids, but it had little effect on me. I’d built up immunity to her stare from years of interrogation by the prison guards. I simply told her that Larry and I were so engrossed in the game we were playing that we never heard the bell. Simplicity is the secret to a good fib. I had a gift, and even at age 9 it was already starting to show through. She never doubted me for a moment.

The first part of our plan was a success, but part two involved sneaking a live Canada goose onto a bus and keeping it undetected until we could get it to Larry’s house. Not an easy task. During our 15-minute afternoon recess, we checked the goose and formulated our plan. We were going to have to retrieve the bird quickly, between the time school let out and the buses were loaded. That was when the inmates were the most heavily guarded of all. No prison guard was going to allow one of her inmates to get on the wrong bus. At first it seemed hopeless, but once again my gift came to the rescue. I had a plan.

We watched the clock until there was just three minutes left in our daily sentence. Larry’s hand went up and I watched nervously as Mrs. McBride acknowledged him.

“Mrs. McBride, I left my coat out on the playground. Can I go get it before the busses get here?”

There was the expected one-minute lecture by Mrs. McBride, leaving Larry exactly two minutes to retrieve the goose. I smiled to myself, as my plan was working perfectly.

I was last in line to get on our bus when Larry skidded to a halt right behind me with both arms wrapped around his balled-up coat. Only Larry and I knew what secret it held. We took our usual seats in the middle of the bus. The back seats were always filled with the older fifth- and sixth-grade boys. You invaded their territory at your own peril. The front was always packed with first-graders, so that left the middle for the rest of us.

Larry kept his coat on his lap while I sat next to him, and I put my coat over his for added security. Larry’s house was the second stop; only three short miles to go until we would be home free.

From behind us a blonde head popped up over the seat and looked at us as the bus started to pull away.

“Whatcha got under your coat?” she asked. It was Annie Wilson, the prettiest girl in all of Chester Elementary School, and she was talking to me.

“Ah, um, ah, ah noth . . .”

“It’s a live Canada goose,” Larry interrupted proudly. “I caught it myself at recess.”

“I helped, it was both of us that caught it,” I added quickly.

“You did not,” she mocked. “Let me see it.“

My head was saying no. We were almost home free. But I was experiencing some strange power coming over me. I no longer had control of my actions. Reaching over, I pulled my jacket off the goose and started untying Larry’s shoestrings. Larry must have been under the same strange power because he was helping me. The brakes on the bus started to squeal as it slowed to let off the next passengers. Larry and I froze while they disembarked. The next stop was ours—only one mile to go.

I looked up nervously at the bus driver’s face in the mirror at the front of the bus. We were breaking in a new driver since the salamander affair, and this one never smiled and only spoke when he yelled at someone for breaking the tiniest infraction. With his cropped military haircut and square jaw, he didn’t look like someone that might give a kid a break.

When the bus started again, Larry and I went back to work untying the goose.

What happened next is mostly a blur. I’ve heard that sometimes when something extremely traumatic happens your mind will block it out and you’ll lose all memory of the event. I do remember an explosion of feathers and the sound of flapping wings followed by the terrified screams of first-graders. I also remember looking up at the bus driver’s face in the mirror.

In fact, that was about the last thing I remembered. The look on his face as the goose made its bid for freedom, flapping its way across the tops of the seats toward the front of the bus, would live with me forever.

“I’d never seen a face turn so completely and instantly white like that,” I stated to the warden at my trial. “I don’t remember much after that.”

I was later told that someone managed to push the bus door open and our goose made a clean getaway.

The wheels of justice turned swiftly at Chester Elementary. It would take months of good behavior before the warden let Larry and me outside for recess again, and we did community service by helping the custodian clean bathrooms for the rest of the year. But it was all worth it. We had pulled off the most daring search-and-rescue operation in the long history of Chester Elementary. Navy SEALS would have been proud.

From then on, things changed for the two of us. There was a new respect paid to us by the prison guards and a little envy by the rest of the inmates. Things had changed on the bus, as well. Our third bus driver that fall was a nervous type, especially so when me and Larry got on the bus, but otherwise she seemed nice.

With our new respect, we were invited to sit in the back with the older boys, but modesty kept Larry from taking advantage of the honor. Instead, he was kind enough to sit with Annie Wilson and help her get over the trauma of the wild goose incident, as it was now referred to in bold letters in my disciplinary file.

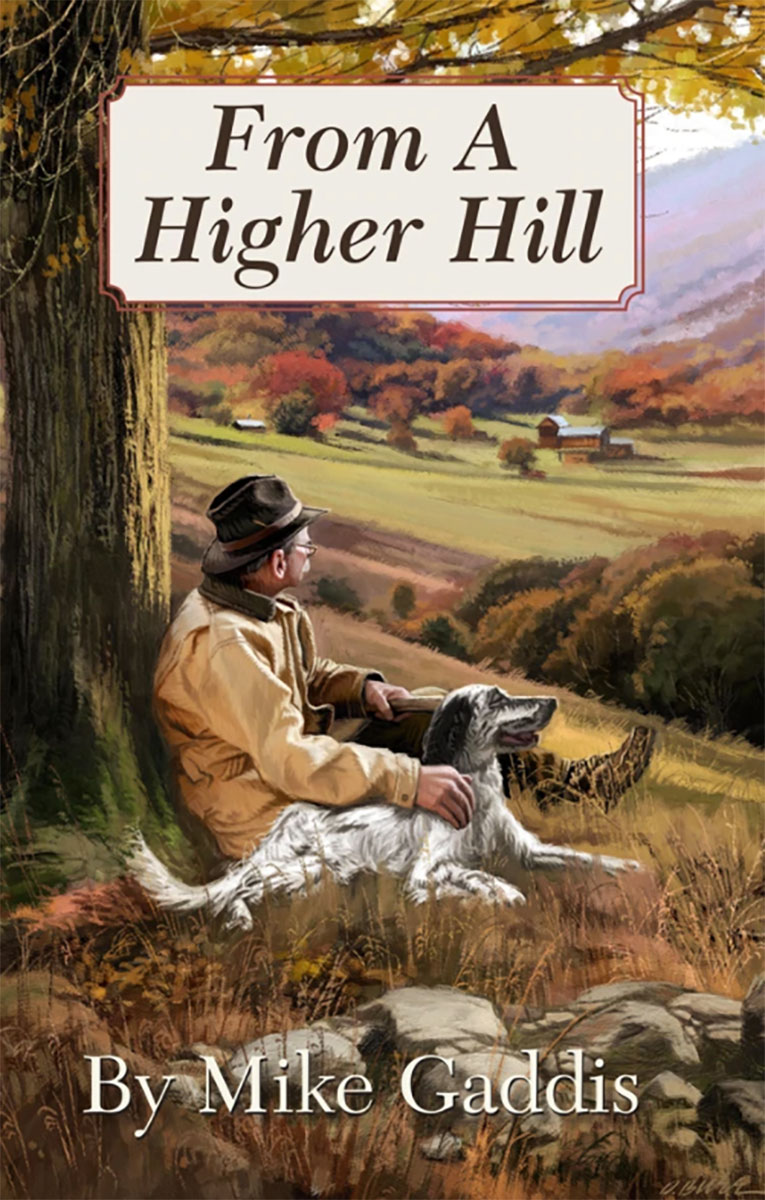

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now