The fame of the game red bird overseas is too well known to require any comment here. Besides, in the matter of grouse, we have troubles not a few of our own. That the British bird is a grand fellow goes without saying, but the question if he be the head of his race from the sportsman’s point of view, is quite another matter.

Consider the grouse—a brave, shy beauty, to whom pen of mine cannot do justice. This bird, the ruffed grouse, is by many considered the king of our feathered game. Nor is the grouse unworthy of the honor. While, to my notion, all things considered, the quail is our best game, I should feel like ranking the grouse an honorable second.

He is indeed a noble fellow. Beautiful in life, crafty and strong in eluding pursuit, and very palatable upon the board, he is all that a choice game bird should be. His sole fault is that there is hardly enough of him in any one place. His pursuit, except in a few favored localities, is a bit too uncertain to satisfy the average sportsman—too long between drinks, as it were. Yet I have seen ruffed grouse shooting which, in spots, was as full of action as quail-shooting. But such memorable occasions are rare. Perhaps a dozen times, during a shooting career of about a quarter of a century, it has been my blessed fortune to blunder into a red-hot ruffed grouse corner. I say “blunder” advisedly, for no man has a license to say when and where he will find such sport.

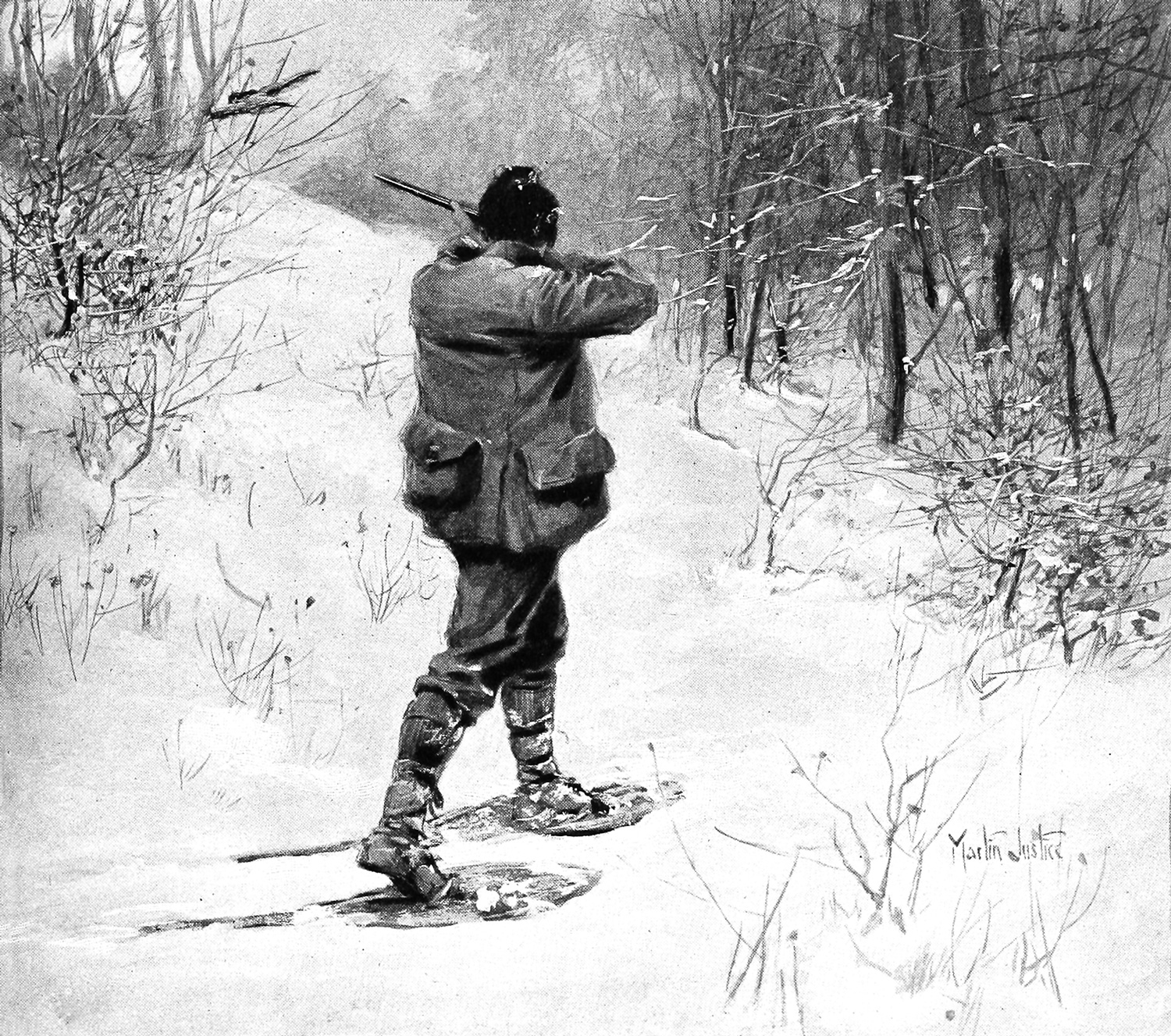

Drawing by Martin Justice

In the “popple” region of Michigan, in the beautiful glades of Wisconsin, in the flat forest lands of western Ontario, in the northern wilds of that province, and in some covers of the Red River Valley, I have occasionally found grouse in numbers and in cover that rendered possible some really lively shooting. Among the picturesque Pennsylvania hills, too, if memory serves me aright, there were certain hasty things like ruffed grouse which slanted away down deep ravines in defiance of shot.

The grouse of the Pennsylvania hillsides is a problem to be tackled by that man who can with one arm perform two motions at the same instant. I am ambidextrous, but I did not greatly injure the Pennsylvania brand of grouse. I would scale a grand hillside, up and up, amid trees from which the foxgrape hung like living rigging. Now and then would sound a booming whur-r and a glorious something would leap from the hillside and fairly dive for the brush so far below. Most of the time I shot at this something—shot behind it, above it, to one side of it, but, I suspect, never below it. Six, seven, eight times, this something roared and leaped and dived. The ninth time I happened to catch it full amidships. There was a gust of shattered feathers, and the something went a whirling down clear to the trout stream away below. I climbed down after it and eventually bagged a bouncing big grouse. After laboriously climbing all the way back again, I learned that there were no more birds on that particular hillside, so the bag consisted of one.

That sort of grouse-shooting is exactly the thing for those who love the exercise of the sport, and will cheerfully guarantee them all the exercise they can stagger home with.

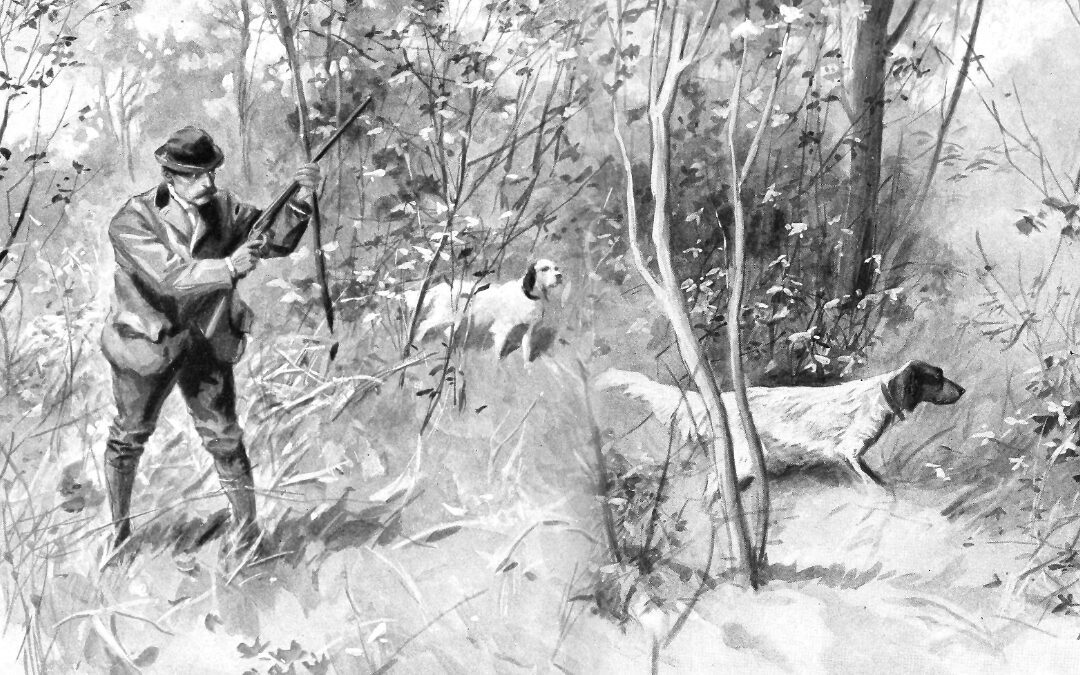

But ruffed grouse shooting is not always like this. I can see a marvelous Wisconsin ravine, a winding corridor, hung with rich tapestry of painted leaves supported by close-standing columns, amid which the snowy birch gleams like marble. ’Tis an ancient roadway, and for two miles it runs between the misty hills. Beside it whispers a foamy rill with smiling pools, where elfin trout tilt at the larvae clinging to floating leaves. Along the roadway proper the footing is smooth enough, but the path is narrowed by crowding briers, among which the ripe haws glow like points of flame. To slowly pace the length of this corridor while the good dog wormed through the low cover was an experience long to be remembered. Ruffed grouse love such places, and birds driven to the heights and not followed would, if flushed in the morning, surely work back by late afternoon. So I had two beats per day.

That sport was as good as any I have seen. About 10 o’clock—there was no advantage in going earlier—I would begin operations. There were two large broods, and each appeared to have its own section of the cover. Owing to the nature of the ground, most birds flushed slightly up the sides, then darted into the corridor and hummed around the first curve, to pitch at uncertain points beyond. The first day the broods rose almost like quail. I got a double shot at the first, and a double and two singles at the second; but on the next visit, a few days later, the birds were strung all along the corridor, and only twice did two rise together.

Now, this was indeed a notable day. The dog knew the ground and worked as steadily as a clock, merely trotting from point to point. And there I was fit and keen, moving along what looked like a gigantic picture-gallery, while the dog drew from side to side as the scent led. A pause, and a grand bird would roar up amid a whorl of leaves, twist in his flight to buzz straight away a trifle higher than my head. Most of those that escaped owed their salvation to the fact that they happened to flush very near a bend in the corridor, around which they whisked too soon for accurate work.

One trip through settled the business until late afternoon. At the farther end I lay at ease, and smoked and talked with the dog until creeping shadows told that it was time for the return trip. Then again the measured advance, the beautiful dog work, the roaring flush, the clean kill, or miss, as the case happened to be. I did not fail too many times. The conditions were too favorable and the whole thing entirely too enjoyable to allow of any serious bungling.

This assuredly was grouse-shooting as one seldom enjoys it, yet had I been a bit wiser more of it would have been my reward. After having practically cleaned out this spot, I sought far and wide for others like it, and to a certain extent was successful. Sometime later I found myself near the corridor, and decided to beat through it on the chance of picking up a straggler. The leaves were nearly all down and the cover was a mere trifle.

Somewhat to my astonishment, the dog at once made game and presently a thunder-wing fellow rose at about 30 yards. I dropped him and, as he hit the brush, another and another bird rose and darted—not along the corridor, as heretofore, but straight up the bank and into the dense woods. As I advanced, birds kept rising at long range, all but the few I succeeded in stopping going like mad for the woods. In the two miles I must have flushed nearly 30, of which I got a half dozen, not one of which fell within 35 yards.

My neglecting the corridor for so long had been a serious error. It was a choice spot, and I should have remembered that what is good for one lot of birds will doubtless prove as attractive to others after the original tenants are gone. While I was seeking other grounds, the leaves fell and so changed the conditions that birds would no longer lie reasonably close.

There were other places—in Michigan. One was what the natives term the “popple” country—it offering what sportsmen of the eastern states would call easy brush-shooting. There were plenty of birds, too—15 to a gun being a good but by no means extraordinary bag. But my fairest Michigan memory is of another spot—a couple of hundred acres of easily rising ground—just enough slope to furnish life to a couple of sweet-voiced brooklets. All of this slope was snarled with briers and ringed by unbroken forest. To beat the open uphill, and stop the grand fellows as they stormed out of the brush and streaked away up the long slope, was a joy which would make a man forget his home, his wife, his ox and his ass—in fine, everything that was his except dog and gun and the privilege of being on that ground!

Nor did that mine peter out. It was good for two days a week, because it was an ideal ruffed grouse ground, and the solemn woods all about held unnumbered birds in nearly absolute safety. The keenest of men and the truest of guns could do little in the heavy standing timber. Your grouse, in such a range, has a nasty habit of whisking behind the first convenient trunk and then keeping that trunk between himself and the gun until he has whizzed past the danger zone.

I tried the woods a few times, only to win vexation of spirit and almost deadly doses of disappointment. There is no fun in filling tree trunks full of shot, and the birds almost invariably treed a couple of hundred yards away. To follow these, to crane one’s neck till it hurt, to finally detect a bird sitting bolt upright upon some lofty limb and to deliberately pot the said bird on its perch, was at best a stupid performance.

And there is another form of grouse shooting for which I confess a weakness. This is still-hunting, or trailing the birds on the snow. I’m afraid that sportsmen who scoff at this hardly understand the game. There is much more in it than meets the ordinary eye. You, of course, use no dog. When a new snow falls, the woods are like so much clean paper, and the furry and feathered folk are so many unintentional scribblers. To the man who knows, the scribbling is easy and most interesting reading. Here a woodmouse dotted along, dragging his tapered tail; yonder a hare passed at speed, scared by the red rascal that made these dog-like tracks. Small triangles show where squirrels have traveled from nest to storehouse, and larger triangles betray where the cottontails held conference till a soundless-winged owl broke up the meeting. Nor did it adjourn sine die—for one fat unfortunate died where you see that big mark. Alongside a log, in at a knothole, through the hollow and out at the end, run queer small prints in pairs. A snaky, white weasel left that sign and, if you carefully followed it, ’twould lead to the scene of a tragedy. By the stream are larger reproductions of these prints, where the mink has trailed the night long on murderous quest.

And here, amid the tan-leaved dwarf beeches, is something. Oho ! The very sight of it makes you grasp the gun tighter, and you begin to peer ahead and to breathe a bit faster. Those trim prints running yonder in true line were made by a grouse. He may be 20 yards away, or anywhere, and you follow with beating heart and tense muscles. ’Twill be a rush and a roar and a glimpse of brown, and you know it.

What’s this—the end of the track? Yes, and see yonder—Reynard was careless that time. The dainty trail ends with a few marks much farther apart and with streaks between. He ran to the takeoff.

Here is another grouse track leading to the clump of briers. Careful, now—it’s fresh as—Look! Did you not see that brown thing dart from the stump to that tuft of dried fern and brush? Steady, now! He must be right there before you and he’ll go straight away to—Whur-r-r!—almost behind you.

“Why, how the dev…?” Bang!—Bang!

Good boy! The first load’s in that maple 15 yards from your nose, but the quick second did the business. As to how the—ahem! he got almost behind you when you had seen him directly in front—that’s a way he has. He saw you as he ran and before he started to run, so he played a card which usually wins. Go get him, he’s a beauty and stone dead.

What are you breathing so fast for and why do your eyes flash? ’Twas a thriller, and you know it, and you’re prouder of that bird than you’d be of three killed over a dog.

This article originally appeared in the December 1902 issue of Outing.